04 Mar Julia Morgan: Twice a Pioneer

While the pantheon of American architects features many illustrious men—Frank Lloyd Wright, Frank Gehry, Benjamin Henry Latrobe and Thomas Jefferson—the list is incomplete without Julia Morgan, a groundbreaking woman who at once embodies and transcends the definition of an American master designer.

An industrious architect of the twentieth century, Morgan successfully designed more than 700 buildings, mostly in Northern California, during her prolific career. Some of these Gilded Age buildings still stand, most notably Hearst Castle, which represents the capstone to Morgan’s achievements and has since been designated a National and California Historical Landmark.

“My buildings will be my legacy,” Morgan said presciently during her career. “They will be here long after I’m gone.”

Bow Bay

Interior of Bow Bay house, photo courtesy Christy

Curtis and Dwight McCarthy of Coldwell Banker

Morgan’s enduring creations range from public buildings prioritizing function over form to private mansions emphasizing aesthetics, and are mostly concentrated in the Bay Area, where Morgan lived and worked.

However, one stunning example of Morgan’s ability to use the natural elements of a given place to erect a living space at once functional, comfortable, artistically unique and lasting stands along Rubicon Bay’s sandy shores in the southwest end of Lake Tahoe. Here, an expansive nine-bedroom, eight-bathroom, 4,000 square foot mansion looms over The Lake’s famed translucent waters.

The Bow Bay Estate, situated on seven acres with 400 feet of shoreline, represents Morgan’s vision as it pertains to Lake Tahoe’s distinct architectural flair.

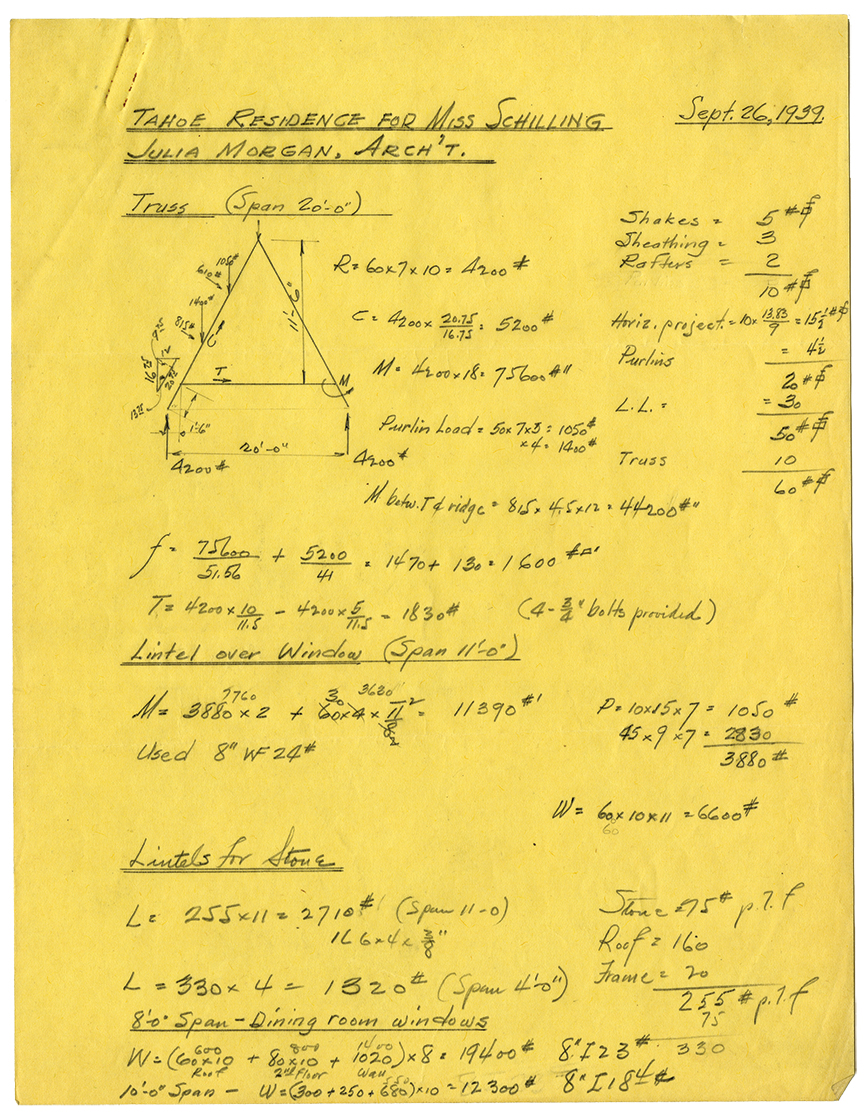

Engineering calculations and sketch by Walter L. Huber

for Schilling Tahoe Residence (Bow Bay), image courtesy

Julia Morgan Papers, Special Collections and Archives,

California Polytechnic State University

Morgan was a proponent of the Arts and Crafts Movement, which permeated nearly all elements of design, particularly between 1880 and 1910. The movement embraced ancient craftsmanship, as opposed to a more assembly-line style of mass production, and called for the use of natural materials evoking a given time and place.

For Morgan, who tended toward building palatial residences, the use of stone and granite collected from Sierra Nevada scree fields and the integration of the pine, cedar and redwood that define the West Coast’s forests was paramount.

Morgan designed Bow Bay in 1939 with the input of owner Else Schilling, a San Francisco spice and coffee heiress. Built in 1944, the home stands today and sold for $14 million in 2014—the largest calendar-year sale in the Tahoe-Sierra MLS.

Schilling wanted the house to resemble a Bavarian or Austrian mountain cottage. The home’s rustic exterior is constructed with local rock and vertically aligned cedar beams, with steeply pitched roofs. The exquisite living room woodwork includes exposed, deeply curved beams resembling an ancient ship’s bowels. The bedrooms scattered throughout the house feature distinctive wood paneling interrupted by windows looking out on Lake Tahoe’s blue waters or back into the West Shore’s pine-dominated forest.

Throughout the estate, there is an odd, contradictory combination of simplicity and grandeur—a trait that marks the majority of Julia Morgan’s creations. The viewer is not only struck by it when viewing the house from the outside, but carved wooden friezes and decorative touches offsetting the open living spaces imbued with natural light carry the feeling to the interior.

This is, of course, by design.

“Architecture is a visual art, and the buildings speak for themselves,” Morgan said.

Bow Bay house, photo courtesy Sara Holmes Boutelle Papers, Special

Collections and Archives, California Polytechnic State University

Every Advantage

Morgan was born on January 20, 1872, a scion of a prominent East Coast family successful in politics, the military and business.

Her father, Charles Morgan, moved his family westward in hopes of capturing a piece of the rapidly expanding nation. Despite the Morgan family’s history of financial success, Charles failed in most of his ventures and the family relied on sizable contributions from Julia’s maternal grandfather, Albert Parmelee.

In 1878, when Morgan was 6, she travelled to New York to stay with her mother and her extended family for a spell. It was there she encountered Pierre Le Brun, a successful architect, who encouraged her to pursue higher education and kindled her interest in structural engineering.

After returning to Oakland, Morgan declined to follow her mother’s suggestion that she debut in society. Instead, she focused on embarking on a career.

The young female scholar, who excelled in mathematics, enrolled in the civil engineering program at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1890. Here, she met architect and lecturer Bernard Maybeck, who encouraged Morgan to move to Paris and enroll at the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, widely considered the world’s most prestigious architectural school.

Morgan followed the advice, moving to the European capital in 1896, but her efforts to enter the academy were rebuffed—twice. Morgan remained undaunted.

In a letter to her family back in the States, Morgan wrote, “I’ll try again next time anyway even without any expectations, just to show ‘les jeunes filles’ are not discouraged.”

The academy eventually relented and Morgan became the first woman to be admitted to the illustrious institution.

California-based philanthropist Phoebe Hearst noticed Morgan’s feat and sent her a letter offering to pay the entirety of her Paris education.

Morgan thanked her and politely declined, but the two women forged a lasting relationship that would eventually lead to Morgan’s most significant and enduring achievement as an artist.

Opportunity from Disaster

After earning a certificate from the school in Paris in 1902, Morgan sailed home to work in the office of John Galen Howard, who delivered one of the most infamous back-handed compliments of the century when discussing Morgan in a letter to a friend, describing her as an “excellent draftsman whom I have to pay almost nothing, as it is a woman.”

In 1904, Morgan opened her own architectural business, becoming the first woman to earn an architectural license in California.

In 1906, San Francisco was destroyed, literally.

A 7.8 magnitude earthquake struck about two miles offshore from the burgeoning metropolis. While the earthquake was large and lethal, about 30 resulting fires, caused by severed gas mains, were responsible for the greatest devastation. After the smoke cleared and charred vestiges were removed, about 80 percent of the city was gone.

One structure remained, though: a freestanding bell tower on the campus of Mills College built by Morgan, then little known.

As the city rebuilt, Morgan earned the commission to rebuild the Fairmont Hotel. The idea of a female architect was so novel that a local newspaper sent out a reporter to confirm that a woman was in charge of the renovation project. The reporter had to be convinced by Morgan and other workers that she was, indeed, the architect and not an interior decorator.

Aware of her pioneer status for women in architecture, Morgan made no bold speeches, preferring instead to go about her business in a quiet, efficient and competent manner.

An American Castle

Morgan already had a list of architectural credits to her name—including the North Star House in Grass Valley, designed for the mining engineer Arthur De Wint Foote and Mary Hallock Foote, who would win lasting fame as the subjects of Wallace Stegner’s Pulitzer Prize–winning epic The Angle of Repose—but it was not until April 1919 that she would earn a commission cementing her place in the pantheon of great designers.

William Randolph Hearst, who owned what would become one of the nation’s most diversified media and information companies, met Morgan via his mother, the aforementioned Phoebe Hearst.

Hearst was looking to build a house on a hilltop at San Simeon where his parents had taken him camping many times during his youth.

The Hearst Castle’s Roman Pool. Photo courtesy California State Parks

Hearst dubbed the project La Cuesta Encantada, or “The Enchanted Hill.” This sumptuous estate incorporates Mediterranean art with Mediterranean Revival architectural design. The design and construction spanned nearly three decades. The entire estate features 58 bedrooms, 60 bathrooms and 18 sitting rooms with 127 acres of gardens along with a private zoo and the famously opulent Neptune Pool.

In 1957, six years after Hearst’s death, the Hearst Corporation generously donated the castle to the state of California; the estate continues to attract hundreds of thousands of visitors annually. It fulfilled Hearst’s wish for the castle to become a museum, allowing the public to enjoy wonderful art collection and beautiful gardens in a grand setting.

In 2008, then-Governor of California Arnold Schwarzenegger and his wife, Maria Shriver, announced that Julia Morgan would be inducted into the California Hall of Fame.

“In many ways [Morgan’s] work is original, masterful and enduring,” said food activist Alice Waters, who was also honored at the ceremony. “The buildings designed by Julia Morgan represent a time when California matured from wild, untamed frontier to a sophisticated, cultivated, industrious, creative force.”

Finally, in 2014, the American Institute of Architects bestowed its highest honor, the Gold Medal, on Julia Morgan, the first and only female architect to receive the distinction. The award solidifies her legacy as one of the great architects of her time, to which her buildings in Tahoe, San Francisco and the Central Coast attest. But she will also endure as a pioneer in the women’s rights movement, proving that drive, purpose and talent can overcome obstacles.

As Alice Waters said: “Julia Morgan’s greatest accomplishment isn’t the work; it is that she did it at all.”

Matthew Renda is a Santa Cruz–based writer.

No Comments