27 Jan The Dislocation of Lake Tahoe

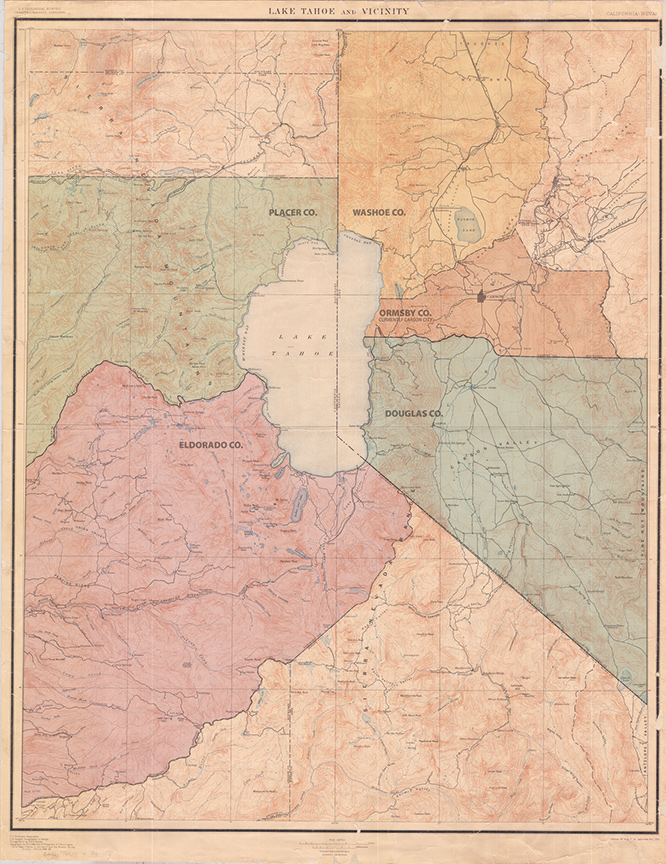

The formation of the five counties dividing Lake Tahoe’s shoreline was more influenced by what happened outside the Basin in the middle of the nineteenth century than what occurred within.

As the destinies of California and Nevada were being set in motion by the progenitors of the American West, Lake Tahoe—the present fulcrum of the Northern Sierra—was an afterthought, a convenient landmark.

The attention of the region’s founders was focused elsewhere. On the California side, in the Sierra foothills, prospectors extracted enormous troves of gold as waves of emigrants rushed to join them. In Nevada’s valleys, a scattershot of settlers set up trading posts in hopes of intercepting overland pioneers, providing much needed replenishment after brutal treks through the desert.

No one lived at Tahoe year-round until the twentieth century.

Thus, Lake Tahoe’s fragmented jurisdictional hodgepodge results from the establishment of county seats in the outlying foothills and valleys combined with the necessity for each county to adhere to east/west configurations along vital transportation routes while vouchsafing access to timber resources that fed the burgeoning mining industry.

California Gold

El Dorado County, which occupies about 29 percent of Lake Tahoe’s 75 miles of shoreline, was founded in February 1850, preceding California’s official statehood by seven months.

The county’s primacy is due to an important discovery made by a sawmill worker inspecting a tailrace portion of a sawmill near the American River on the morning of January 24, 1848. That’s when James Marshall, a carpenter charged with overseeing the construction of Swiss pioneer John Sutter’s sawmill in Coloma, noticed glinting flecks of material that after repeated testing was confirmed to be gold.

The discovery’s announcement—made two weeks before Mexico granted California to the United States as part of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo—precipitated one of the largest human migrations in history.

As the birthplace of the Gold Rush, El Dorado’s county seat was founded in Coloma, but moved to Placerville (then-called Hangtown after its proclivity for capital punishment) four years later.

The jurisdiction featured one of the first trails used by land travelers from the east bent on clambering over the Sierra Nevada’s tall spine.

The Carson Trail, alternatively known as the Mormon Emigrant Trail, brought adventurers who safely crossed the pitiless desolation of the Great Basin into the Sierra foothills, where a teeming population of prospectors dotted the hills. It is estimated that 90,000 people arrived in California in 1849, with a full 300,000 making their way to the gold fields during the Gold Rush. Soon, the hills throughout El Dorado County became infested with mining claims and overrun by febrile men hungry for gold, many of whom moved north into Placer County.

Placer County, which accounts for 41 percent of Lake Tahoe’s shoreline (by far the most), was established in April 1851, about three years after the onset of the Gold Rush.

Frenchman Claude Chana is credited with discovering gold in the Auburn Ravine in May 1948. Soon after, the county seat of Auburn was established, which began to flourish as a supply camp for the growing array of miners spangling the foothills.

The configuration of the county followed the flow of the watershed that ran west from the high-elevation headwaters.

All of the counties that comprise California’s Gold Country, nestled on the western slope of the Sierra Nevada, retain a skinny east to west formation.

The mines were located predominantly in the eastern parts of each county.

The west featured vast stands of timber used to build towns, to bolster underground workings and to carve out the roads through the mountains that brought an influx of new settlers every day and took the letters back home.

Nevada’s Rush

Those snowy roads and those arduous Sierra crossings were critical to Nevada’s settlement, too.

From the Gold Rush’s beginning in 1849 until Nevada’s inclusion into the United States in 1864, the vast tract of land was part of the Utah territory and was governed by members of the nascent Mormon religion.

Douglas County, which accounts for 13 percent of Lake Tahoe’s shoreline, was founded in 1861, along with several other present-day counties three years prior to the Silver State’s embattled birth.

Douglas County, named after the great debater Stephen A. Douglas, is considered to be Nevada’s cradle as it boasts the state’s first settlement, Genoa. Here, the aforementioned Carson Trail begins to surmount the Sierra spine.

It was in January 1844 that explorer John C. Fremont and his famed guide Kit Carson marshaled a rugged band of explorers and launched from Genoa, slithering their way through the snowy heights of a path that today follows Highway 88. It was during this trek, on February 21, 1844, that Fremont and cartographer Charles Preuss summitted Red Lake Peak and became the first men of European descent to ever lay eyes on Lake Tahoe.

In the following years, settlement at Genoa grew as Mormons chafing under the rule of leader Brigham Young moved into the region and established trading posts.

Judge Orson Hyde was sent to Genoa by the Utah Territory governor in 1854 to consecrate a government and hold elections. Hyde, a Mormon who was accompanied by his fourth wife, filled many of the county seats with officers who were vastly under-qualified, but would follow the laws out of Utah, which then included polygamy. Hyde, and many of the Mormon officials, returned to Utah just a few years later.

Most historians identify H.H. Jamison as the first settler to occupy what is now Washoe County, which occupies 11 percent of Lake Tahoe’s shoreline. Jamison founded a supply store along Steamboat Creek, about three miles southeast of the present location of Sparks. Like Genoa, the settlement thrived as it served provisions to the steady stream of easterners lured by legends of riches interred in western hills.

Emigrants arriving in Washoe County often opted for the Truckee Trail, pioneered by the Stevens-Townsend-Murphy party—the first to bring wagons over the Sierra Crest in November, 1844, two years before the Donner Party’s ill-fated attempt.

The historic trail is today demarcated by Interstate 80.

Finally, another Sierra crossing spurred the growth of Carson City, as the famed Johnson Cutoff was discovered in 1850 by John Calhoun Johnson. Johnson hit upon the shortcut while carrying mail on snowshoes from Nevada City—a growing mining town—to the sparsely populated Carson City.

The cutoff, which follows the same route as U.S. Highway 50—from Placerville, up Echo Summit, along the South Shore of Lake Tahoe and down into Carson City—replaced the more arduous and highly-elevated Carson Trail and led to the rapid growth of Carson City.

That growth was augmented by the discovery of the Comstock Lode in 1859, causing a silver rush and the emergence of thriving mining towns in Virginia City and Gold Hill.

The influx of miners from California, where mines were drying up, prompted the official creation of the three Nevada counties that border Lake Tahoe in 1861 as the once-barren territory advanced toward statehood.

Lake Tahoe

The discovery of the Comstock Lode marked the beginning of Lake Tahoe’s modern history as miners busy bolstering the underground workings demanded large amounts of timber supplied by the forest populating The Lake’s shores.

Loggers staked spike camps, mostly along Lake Tahoe’s East Shore, and workers built a flume capable of conveying wood over the crest of the Carson Range.

From about 1860 until 1890, the Lake Tahoe Basin was logged out; the denuded landscape extended around the entire lake rim except for a few pockets along the West Shore.

A few hardy souls would brave the formidable winters, but it was not until the turn of the century that Lake Tahoe began to emerge as a tourist destination and a place where year-round habitation was possible.

The fractured oversight presented by several counties became problematic after the 1960 Winter Olympics at Squaw Valley USA etched Lake Tahoe into international consciousness and prompted rampant development throughout the Basin.

The Tahoe Regional Planning Agency (TRPA) was created in 1969 to curtail the development many scientists blamed for significant degradation of the Basin’s ecology and the famed clarity of The Lake. Since, counties have been encouraged to collaborate rather than compete.

“Listen, it’s just not the same lake it was 40 years ago, where everybody is fighting over their slice of the pie,” says TRPA spokesman Jeff Cowen. “Cobbling together the efforts of those jurisdictions is the primary responsibility of the TRPA.”

Despite the ostensible harmony personified by the five county representatives that sit on TRPA’s governing board, the idea of consolidating the counties in each state is occasionally bandied about.

Proponents of the theory say decision makers would be more attuned to the specific and complex needs of Lake Tahoe and its constituents, rather than building budgets with an eye down the hill.

Placer County supervisor Jennifer Montgomery, for one, isn’t buying.

“There would be an outcry over a proposal for a new county,” Montgomery says. “Lake Tahoe and the Sierra Nevada are important to my constituents economically, historically and emotionally. There would be huge opposition.”

Matthew Renda is a Nevada City–based writer.

No Comments