01 Mar Sly Designs: The Architecture of Henrik Bull

If you haven’t noticed the work of notable Bay Area architect Henrik Bull, that’s by design.

Bull’s architectural maxim dictates that structures integrate into their settings, particularly when recommended by the natural surroundings.

“Architects need to work with the land rather than on the land,” Bull said in a series of recorded interviews provided to Tahoe Quarterly by the Bull Stockwell Allen (BSA) architectural firm.

John Ashworth, a principal at the BSA Architects firm Bull co-founded in the late 1960s, says Bull despised architects who attempt to make grand pronouncements with their design while ignoring how the building functions in the overall landscape.

“Henrik wanted the building to enhance the natural setting,” says Ashworth, who considers Bull a mentor. “He wanted anyone who looked at the building to feel as though it had always been there, that it belonged at this particular site.”

Bull died in December 2013, but his approach to design, pairing modern architectural sensibilities with a sensitivity to the site, continues to influence architecture throughout Northern California—particularly in the Lake Tahoe Basin.

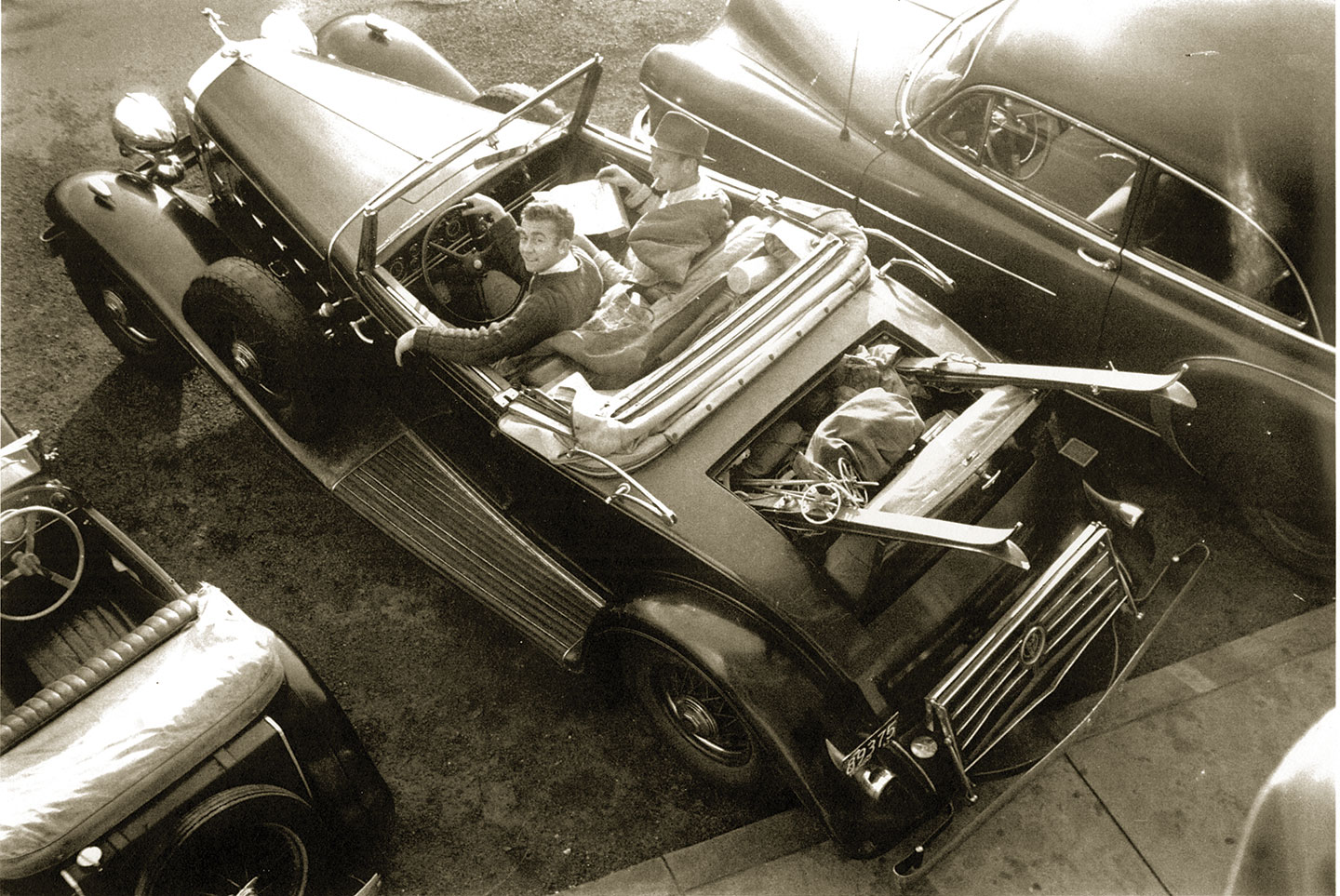

Famed architect Henrik Bull (driving) was drawn west from New England by his love of skiing and frequently

slept overnight in the Squaw Valley parking lot in order to ski first thing.

Westward the Course Moves

Henrik Bull was born in New York in 1929, the son of Johan Bull, who immigrated to the United States from Norway and became a successful illustrator for The New Yorker magazine. The younger Bull spent his formative years in Vermont, where he encountered, cultivated and developed what would become the chief passion of his life—skiing.

“The loves of Henrik’s life were: number one, skiing; two, architecture; and then his family came later,” says Barbara Bull, Henrik’s wife of more than 50 years. “He was a beautiful skier, quite graceful.”

In between carving turns on the ice-ridden slopes of the Green Mountains, Bull managed to apply himself to study just enough to be admitted into the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Initially, Bull enlisted in MIT’s aeronautical engineering program, later saying aviation was the fixation of every young person of his generation who displayed mathematical aptitude. However, some of his classmates intervened, enjoining Bull to pursue an architecture degree, where he found a vocation that not only used his skills but allowed him to continue to ski.

Degree in hand, Bull, as he told it, got into a car with three of his fellow MIT graduates and drove in shifts across North America without resting. The group was attempting to arrive in San Francisco before the Cal Berkeley semester ended and increased the amount of competition pounding the pavement in search of that coveted first job in the field.

Bull is credited with first designing a mountain town staple: the

A-frame cabin, in Stowe, Vermont.

Squaw Valley

Barbara Bull estimates her husband landed in San Francisco in 1954, where he secured employment as a draftsman at an established architectural firm. In his spare time he designed ski cabins.

In 1953, prior to the western excursion and while still situated in the East Coast, Bull designed what many to believe is the first A-frame cabin, located in Stowe, Vermont.

“He’s pretty much credited with its invention, although there are a couple that appeared at the same time,” Ashworth says. “No one knows absolutely for sure who did it first, it’s just one of those zeitgeist things.”

Indeed, A-frame cabins began cropping up all over the Lake Tahoe Basin in the 1950s and ’60s. During this postwar period, many middle-class Bay Area workers began to view Lake Tahoe and the Northern Sierra as an ideal location for a second home. Accordingly, the A-frame increasingly became the prototypical design for a rustic mountain cabin.

Yet, ironically, Barbara notes that while her husband pioneered the design, he never built a single A-frame in the Sierra.

Bull got away from the design, feeling it was inadequate in terms of solving the problem of snow distribution on a given site, Ashworth says.

“When the snow slides off the roof, it creates problems when it hits the ground and then can hit the building,” Ashworth says. “Henrik also realized there were benefits to keeping the snow on the roof, in terms of insulation value. So he moved to more simple roof forms.”

Roofs were an obsession with Bull, who described the modern architectural movement’s fixation with flat roofs as near religious zealotry.

“Architecture is the study of light and space,” Bull said in the videos provided by BSA Architects. “If you start off with a flat ceiling, it is difficult to make the space exciting. So I began to realize the expression of the roof is important.”

With this architectural philosophy in mind, Bull set about designing a modest ski cabin that a friend, Peter Klaussen, wanted built in Squaw Valley. It was 1955 and Squaw, which had opened in 1949, was just blooming into the world-class ski destination it is now.

Later in life, Bull would prefer flat-roofed designs for mountain building, as shown at

Squaw Valley’s Peter Klaussen Cabin.

Bull and Barbara were very familiar with its setting, as they often slept overnight in their Volkswagen Bug so they could wake up next to the lifts in the morning.

“We were young and the world was our oyster,” Barbara says.

Squaw Valley was perched on the precipice of 1960, when the Olympic Games would lead to explosive development throughout the Truckee/Tahoe region.

When Bull first submitted his design to Klaussen, his Harvard-educated friend was unimpressed and challenged Bull to be more creative. So goaded, Bull came up with the design that would alter and ultimately launch his career.

Sunset Discovery House

Bull instead designed an innovative, 850 square foot cabin that highlighted the expansive view of KT-22’s slopes to the southern end of the property. With two triangular roof sections, the Klaussen cabin caught the attention of many admirers.

On the front cover of its May 1958 edition, Sunset Magazine featured the cabin as its Sunset Discovery House, generating publicity and praise for Bull’s burgeoning foray into the field of mountain architecture.

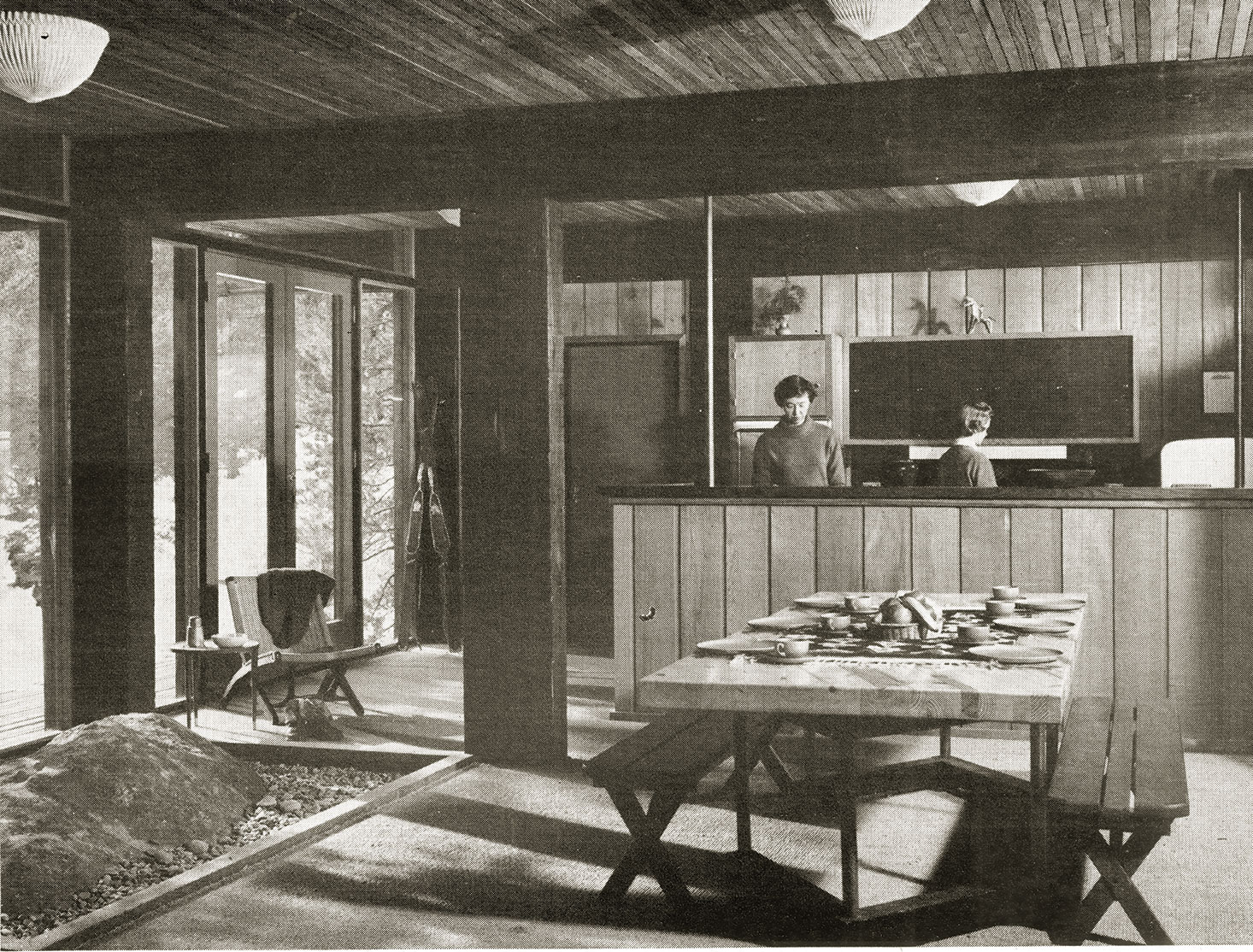

The interior of Squaw Valley’s Peter Klaussen cabin, one of the works that propelled Bull to fame. Heavy timbers

divide the interior living space from the kitchen, which opens onto a deck overlooking the creek below the home.

“When those photos were published it allowed him to get his market,” Ashworth says. “And it was an incredible market at the time. He was able to get up into Tahoe right at the time of the 1960 Olympic Games.”

All told, Bull designed about a dozen ski cabins in Squaw Valley, some of which have since been torn down. He also designed and built ski cabins around Cascade Lake and other parts of the Lake Tahoe Basin.

“In a way, he was just trying to make skiing pay for itself,” Ashworth says.

But, as an architect he was dedicated to problem solving. Bull was particularly attracted to building cabins that could manage loads from the particularly heavy snow that falls on the Sierra Nevada.

“Henrik saw architects designing sloping roofs right over driveways,” Ashworth says. “Steep roofs with dormers and other things that can rip apart the gutters and just aren’t taking into account snow country.”

Bull not only paid special attention to modest roof slopes and their positions away from doorways and driveways, but he was also intent on using locally sourced materials such as wood and stone gathered from Tahoe forests.

In this manner he was an adherent of the Bay Area style pioneered by the likes of Julia Morgan, Bernard Maybeck and Ernest Coxhead. A combination of the British Arts and Crafts movement with significant influences from Japanese architecture that sought to integrate and enhance natural elements of a structure’s surroundings, the Bay Area style also cultivated an indoor/outdoor relationship made possible by California’s beneficent weather.

“The architecture in the Bay Area at the time was quite different from that on the East Coast,” Bull said in the recordings. “It was influenced more by Asia than Europe and it encouraged a closer feeling with nature.”

Genesis of the Firm

Having made a name for himself with the Klaussen cabin, Bull launched out on his own.

At first, the trickle of commissions to build modest ski cabins was enough to sustain his entrepreneurial enterprise. However, Bull reckoned that by joining with other architects of a similar mindset he could bring in more and bigger bids.

“He went out to lunch with some of his fellow architects—John Field, Woody Stockwell and Dan Volkmann—and they realized they were going after the same housing projects,” says Sarah Mergy, an associate principal at BSA Architects.

The firm was founded as Bull Field Volkmann Stockwell Architecture Firm in 1968. Yet, Bull maintained his own niche as a ski country architect.

In the late 1960s, Bull designed and built the Tahoe Tavern Condominiums near Tahoe City, the first high-end condos in the Lake Tahoe Basin. The design won a Governor’s Award. The buildings are a distinctive example of Bull’s use of natural local materials to convey a sense of warmth and integration to the viewer.

Designed for the Douglas Fir Plywood Agency in 1959, Bull fashioned this lakeside summer

cabin out of two 16X20’ plywood boxes separated by a deck covered by canvas for shading.

It wouldn’t pass code today as the cabin’s plywood walls were not insulated, but in 1960 it

cost $3,200 to build.

“When you have texture to a surface, it implies warmth,” Bull said. “Steel is cold. In the vocabulary of experience when you say he or she is warm person, this is a positive thing.”

The firm secured the commission to design the Northstar-at-Tahoe resort in 1971, one of the first large projects it brought in as a result of its collaborative approach. Ashworth says Bull came to regret some of the more “trendy” elements of the resort design, but the successful completion of the commission allowed the firm to get several more large projects.

BSA Architects and Bull in particular designed the Bear Valley Visitors Center at Point Reyes National Seashore, which garnered a President’s Design Award. The now-famous building has the appearance of a rustic barn that has been on the land since the homesteading days of early California.

“When I was designing it, I knew it ought to look like it’s always been there,” Bull said. “Sensibly, the one thing that would look like it’s always been there is a barn.”

This type of creative humility and dedication to finding the elegance in simplicity accounts for why Bull garnered more than 70 design awards over the course of his career and why his heritage continues to live on in the architects he mentored at his firm.

Ashworth, still landing notable commissions at BSA Architects, says Bull was like a second father to him. Ashworth designed the Sand Harbor Visitor Center on the East Shore of Lake Tahoe, and its use of natural wood elements and its chameleon-like ability to blend with its surroundings harken back to the master.

“His projects have a timeless authenticity to them,” Ashworth says.

For this reason, the fruits of Bull’s labor appear poised to endure.

Matthew Renda is a Santa Cruz–based writer.

No Comments