22 Jun A Long, Strange Trip

Nevada Museum of Art exhibition traces the history and evolution of Burning Man

Among the tens of thousands of diehard “Burners” stretching the globe, only a select few know the history behind the countercultural phenomenon quite like Michael Mikel.

With the assistance of Mikel and other Burning Man progenitors, the Nevada Museum of Art (NMA) in Reno did its part to bridge that gap in knowledge with its new exhibition: City of Dust: The Evolution of Burning Man.

“This is the first exhibition any institution has done that really opens up the vault of the Burning Man founders and people who were involved in the early years,” says Amanda Horn, NMA’s director of communications.

Running from July 1 through January 7, 2018, City of Dust is a culmination of years of research and stockpiling from the archives of Burning Man’s founders—including Larry Harvey, Harley Dubois, Marian Goodell, Will Roger Peterson, Crimson Rose and Mikel. The exhibition includes over 300 objects ranging from historic documents and photos to original architectural sketches and journal entries.

“It’s a mix of these archive materials, allowing the objects to tell the story,” Horn says.

This Key to Black Rock City is one of over 300 objects on display at the City of Dust: The Evolution of Burning Man exhibition, photo courtesy Nevada Museum of Art, gift of Will Roger Peterson

This Key to Black Rock City is one of over 300 objects on display at the City of Dust: The Evolution of Burning Man exhibition, photo courtesy Nevada Museum of Art, gift of Will Roger Peterson

Many of these materials were procured from Mikel’s extensive collection, which dates back to the seminal Burning Man events that took place in the late 1980s on San Francisco’s Baker Beach.

“I have a keen interest in history, and so I’ve saved pretty much everything since the beginning,” says Mikel, 72, who now serves as the Burning Man Project’s director of advanced social systems. “I’m basically the Burning Man historian because I’ve kept the most accurate records and files. So I’m really excited to see this stuff preserved.”

NMA’s Ann Wolfe, who co-curated the exhibition along with Bill Fox, adds that City of Dust not only traces the evolution of Burning Man, it provides insight into the logistics of creating—and regulating—a temporary city of 70,000 people in the middle of a desert.

“I think part of what makes this interesting is that you do not necessarily have to have attended Burning Man,” she says. “Anybody who is interested in urban planning, urban design, civic design, community development, the growth of communities—that’s what this exhibition is really about.”

San Francisco’s Baker Beach, shown in 1989, was the site of the early Burning Man events, photo courtesy Nevada Museum of Art, gift of Stewart Harvey

San Francisco’s Baker Beach, shown in 1989, was the site of the early Burning Man events, photo courtesy Nevada Museum of Art, gift of Stewart Harvey

Baker Beach Roots

It was 1986, at the height of the Cold War and AIDS epidemic, when Larry Harvey, Jerry James and a dozen artist friends unwittingly kicked off an annual ceremony that became known as Burning Man. They constructed a roughly 8-foot-tall wooden effigy of a man and hauled it down to Baker Beach, located in the shadow of the Golden Gate Bridge.

“They brought their kids—it was just kind of a family picnic—and they decided to burn the figure on the beach on the solstice,” says Mikel. “They poured gasoline on it and it just lit up, and, of course, people came running from up and down the beach. It was great fun, so they decided to continue it each year.”

Mikel joined the party in 1988. The Texas native and Vietnam veteran worked in the Bay Area as an electromechanical systems engineer, “which is basically robotics,” he says, explaining that he was a consultant to Apple computers in the 1980s, when the company was based in Fremont. He also was involved with the San Francisco–based Cacophony Society, a social group with Dadaist roots and anarchic tendencies that gathered monthly “to do fun and unusual things,” Mikel says.

Burning Man co-founder Michael Mikel, photo courtesy Dusty Mikel

Burning Man attendance grew to several hundred people by 1990 after the event was listed in the Cacophony Society’s newsletter. The wooden man also grew in size.

“In 1990, we showed up on the beach with a four-story wooden man, and the authorities came and said, ‘You can’t burn this here. You don’t have a permit and the fire is too big.’ So we made a deal with them that we would just erect the man and have a party around it, but we wouldn’t burn it,” says Mikel.

“So we did that and then we took the man apart and put it in storage, and then a couple months later we saw some videos of this strange place in Nevada—this huge, blank plain—and they were playing a game of croquet, only their croquet ball was 8 feet in diameter and for the mallets they were using pickup trucks. We thought, ‘Hey, we could go out there and burn the man.’ And we did.”

Moving to the Playa

The Cacophony Society considered the initial burn in Nevada’s Black Rock Desert, held over Labor Day weekend in 1990, the fourth event in their series of “Zone Trips”—in which members packed into a van and drove to a distant location for an outing filled with camaraderie and shenanigans. Upon arriving at their destination, Mikel would draw a line in the dirt to symbolize crossing into a new realm. Everyone in the group then crossed the line as one.

“That was the ceremony of the Zone Trips. I would say, ‘On the other side of this line, our reality will change.’ And it changed the way we looked at things. It changed our mental state, and it was very effective,” says Mikel.

Other Cacophony Society rituals became ingrained in Burning Man culture as well, such as dressing up in costumes, and the concepts of radical inclusion and leaving no trace. The latter two are among the 10 Principals of Burning Man, which Harvey wrote in 2004.

Burning Man founders Will Roger Peterson, Crimson Rose, Michael Mikel, Larry Harvey, Harley K. Dubois and Marian Goodell in 2013, photo courtesy of Burning Man Project, photo by Karen Kuehn

Burning Man founders Will Roger Peterson, Crimson Rose, Michael Mikel, Larry Harvey, Harley K. Dubois and Marian Goodell in 2013, photo courtesy of Burning Man Project, photo by Karen Kuehn

As Burning Man attendance increased, participants soon recognized the need for greater organization, which happened to be one of Mikel’s strengths. In 1992, he began editing the first on-site newspaper and formed the Black Rock Rangers, a group of participants who volunteer a portion of their time to ensuring the safety and well-being of others. His involvement earned him the nickname Danger Ranger.

“One thing I realized that was very important during the early days was communication. At the time there was no orange fence around the Burning Man camp, and people would get lost out there. So we got some old used radios and there was six of us, and our first job was search and rescue, finding people and bringing them back to camp,” says Mikel, adding that there are more than 800 Black Rock Rangers today.

Mikel also developed Burning Man’s first computerized mailing list, introduced containerized storage and transport, and instituted the first perimeter radar system. His concept car, “5:04 PM,” was the first art car at Burning Man.

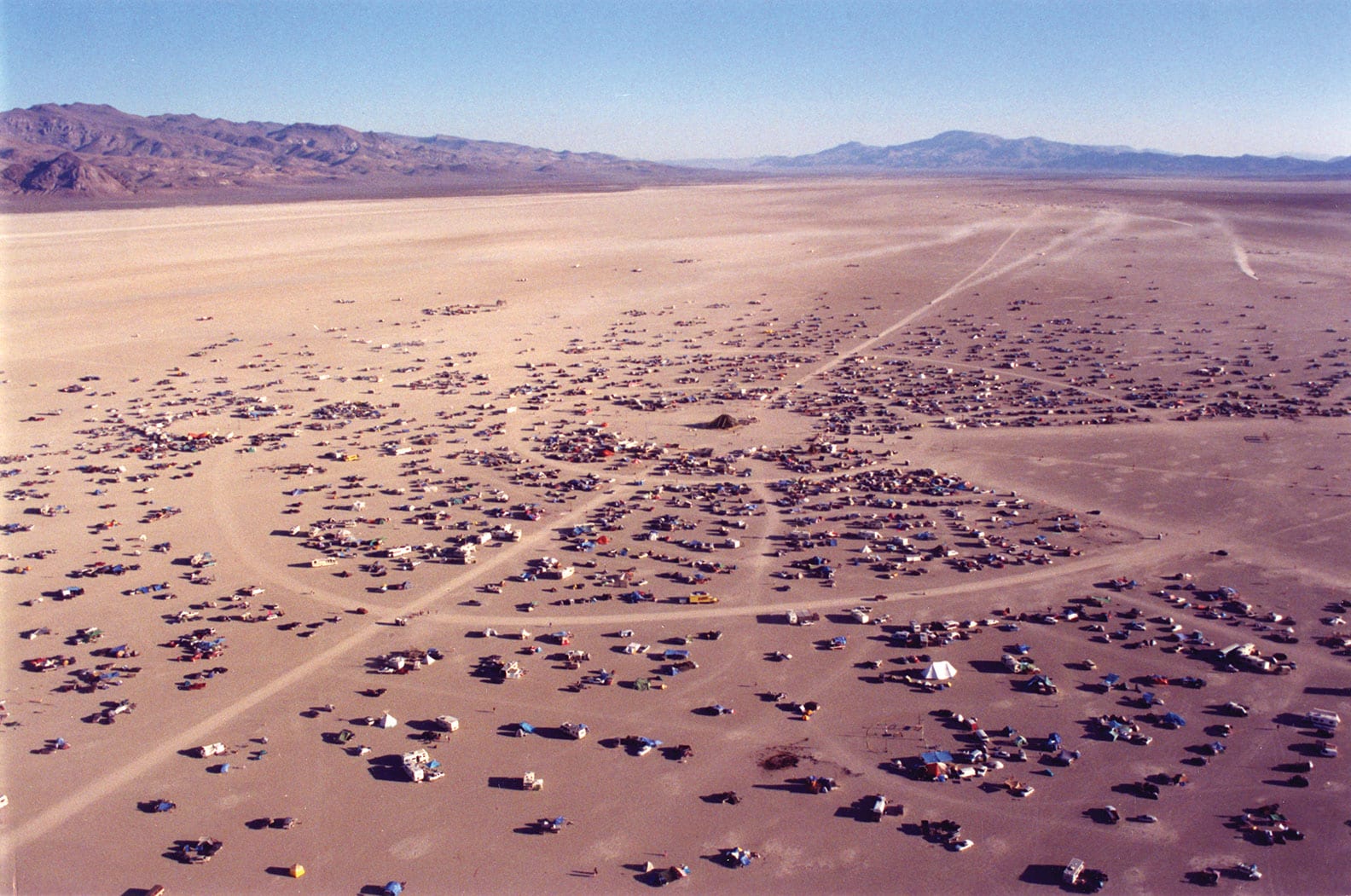

An aerial photo of the 1996 Burning Man gathering, photo courtesy Nevada Museum of Art, gift of Michael Mikel

An aerial photo of the 1996 Burning Man gathering, photo courtesy Nevada Museum of Art, gift of Michael Mikel

Black Rock City

The Burning Man crowd reached 8,000 people by 1996. Following a fatality the same year and a one-year hiatus from the playa—when the event was held on a nearby private property—organizers created Black Rock City LLC. Meanwhile, participation grew to 23,000 people by 1999.

A flurry of civic design and development ensued, reflecting a fusion of utopian aspirations with practical needs for a system of governance, which are evidenced in early city maps, event schedules, newsletters and documents. A circular city design evolved, and the annual population of Black Rock City rose to 30,000 by 2003.

All the while, the annual design, construction and climactic burning of the wooden man—which grew in conjunction with the city, from 40 feet tall in 1990 to 80 feet in 2002 to its maximum height of 105 feet in 2014—anchored the event.

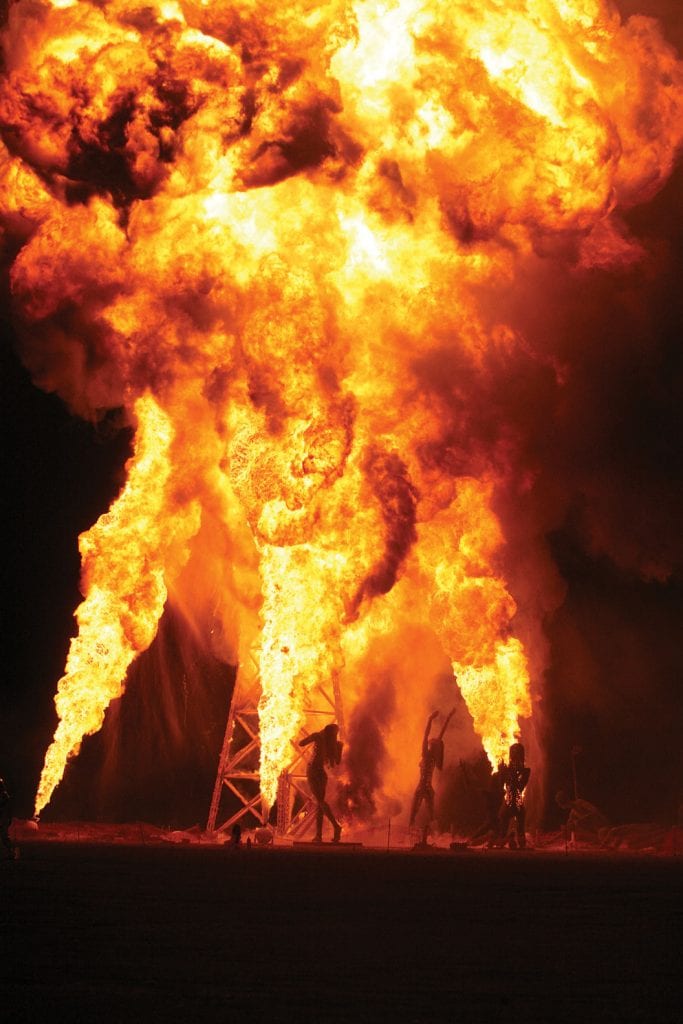

An art piece called “Crude Awaking,” an 80-foot oil derrick worshipped by metal figure, shown in 2007, photo by Ryan Salm

As the organizational structure of the city matured, organizers designed posters to increase visibility and established entry fees to help cover the cost of the infrastructure, including medical services and restrooms, as well as the continually increasing permit fees from the Bureau of Land Management.

Burning Man’s founders, who for years were collective partners in the for-profit corporation, officially converted the organization to a nonprofit entity in 2012, governed by a board of directors known as the Burning Man Project. Mikel is a board member to this day.

“My main role now is looking to the future and planning, and giving talks,” Mikel says. “I’m an ambassador for Burning Man.”

Blazing Ahead

While Burning Man has reached its maximum capacity of 70,000 people—mainly due to congestion issues on the two-lane road leading to the Black Rock Desert—a proliferation of smaller Burning Man–style events have popped up around the globe.

“There are more than 80 regional groups and events around the world, including events in South Africa, Israel and Australia,” Mikel says. “So that’s the phase that we’re in right now, this rapid growth globally.”

Mikel says the Burning Man Project board is also exploring other ideas of how to bring in more people. One option is the use of buses, while a Black Rock City Airport has already been established to meet the demand of those arriving by plane.

Fly Ranch could play a role in Burning Man’s future growth as well. The Burning Man Project organization purchased Fly Ranch, a 3,800-acre parcel of private land adjacent to the Black Rock Desert, in 2016 for $6.5 million.

Burning Man 2011, photo by Ryan Salm

Burning Man 2011, photo by Ryan Salm

“The future of what happens there, we do not know that story yet,” says Wolfe, the City of Dust curator. “But we will have materials related to the deed of purchase from maps and concept designs for what could happen at Fly Ranch. The organization has been looking at the property for many years.”

Regardless of what the future holds, the evolution of Burning Man has been a long, strange trip—far too expansive to fully document here. But after years spent peeling back the layers, the Nevada Museum of Art is now among the foremost authorities on this ethereal event dedicated to community, art, self-expression and self-reliance. The proof is in City of Dust: The Evolution of Burning Man.

“Any time you’re able to look at an event through a historical lens, it gives you perspective, which allows you to understand it differently,” Wolfe says. “This exhibition allows you to understand how [Burning Man] grew spontaneously from this small gathering to what is now: a legendary phenomenon. People who love history, this really provides new insights into what’s otherwise considered kind of a mystique to Burning Man if you have not been there.”

In spring 2018, City of Dust will travel to the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.

“It’s really exciting the depth of the history in this exhibit,” Mikel says, “and I think that’s what’s going to fascinate people.

IF YOU GO

When: July 1, 2017–January 7, 2018

Where: Nevada Museum of Art, 160 West Liberty Street, Reno, NV

Cost: $10 general admission; $8 student/senior; $1 children 6–12; free children under 5, museum members and Washoe and Douglas County high school students

Museum hours: Wednesday–Sunday, 10 a.m.–6 p.m.; Thursdays until 8 p.m.

Contact: (775) 329-3333

Sylas Wright is the editor of Tahoe Quarterly.

1 Comment