09 Dec A New Year’s Deluge

The Flood of 1997 is remembered as one of the Reno–Tahoe area’s worst natural disasters in modern history

The first drops fell on the northern Sierra on a Monday. It was December 30 and the forecasters had warned for several days that an enormous storm system was on track to strike Northern California.

Regardless of the ominous forecast, revelers began to congregate in Truckee, along the shores of Lake Tahoe and down the hill in Reno, where the hotel casinos were short on vacancies.

As residents and visitors prepared to celebrate the New Year’s holiday with convivial floods of champagne, carousal and winter cheer, this holiday season would be marked by a different type of inundation.

A rainstorm that hit the region on December 30 and lasted until January 3 unleashed the Flood of 1997, the most devastating flood the region had seen in nearly a half century—some say it was the worst flood ever—wreaking devastation on communities and the landscape while claiming two lives.

“That is by far the worst I’ve ever seen,” says Dick Kirkland, who was the Washoe County Sheriff in 1996–97. “I wasn’t around in 1955 and some people say that was more, but the flood in 1997 did tremendous damage.”

A confluence of factors conspired to create the flood.

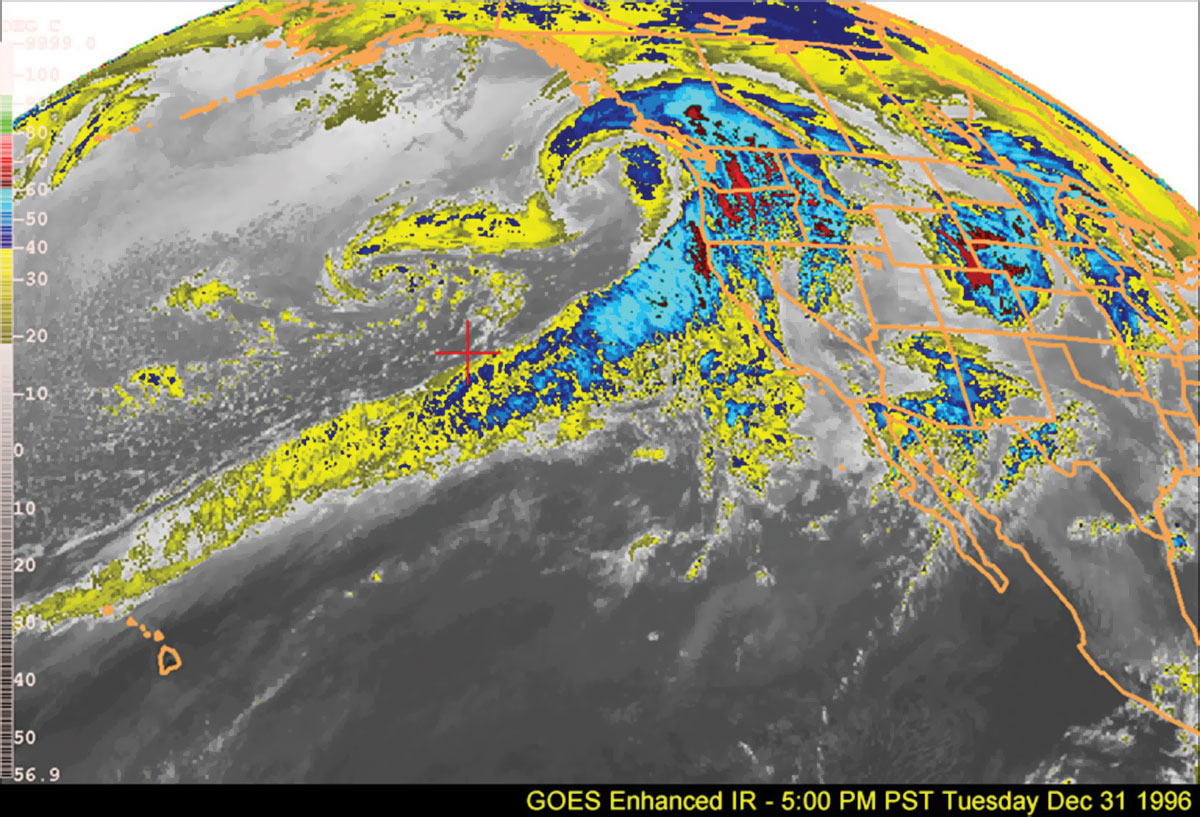

Enhanced infrared image taken at the height of the storm period on Tuesday, December 31, 1996. The imagery shows the tropical moisture from west of the Hawaiian Islands being entrained into the strong zonal Pacific flow to the West Coast. Even more impressive was the wide baroclinic cloud band that delivered the final major New Year’s Day storm, images courtesy National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Weather Service

The Perfect Storm

The storm system that trundled over the mountain pass and hung over Reno and Carson City was a classic Pineapple Express—systems that originate in the South Pacific, normally in the waters adjacent to the Hawaiian Islands, and carry so much moisture that meteorologists refer to them as atmospheric rivers.

Most of the winter storms in Northern California form in the waters off of Alaska. Those systems are colder and carry less moisture as a rule, and when the precipitation reaches the Sierra, it accumulates as the light, champagne powder–style snow that skiers and snowboarders dream about.

In 1996, the Reno–Tahoe area witnessed both phenomena back-to-back. On December 20, a cold storm moved through the region, dumping as much as three feet of snow along the Sierra Crest. Another similar storm hit just after Christmas, meaning a thick base of snow was already established in the Tahoe Basin.

Estimates had the base level anywhere from six to eight feet, substantial considering the winter was just underway.

Then, on New Year’s Eve, the front edge of the Pineapple Express marched over the serrated spine of the Sierra and began to disgorge huge amounts of moisture. What was unique about the storm, according to the postmortems published by various agencies, was not only the sheer volume of moisture contained in the system, but its temperature.

“The extreme warmth of these rains effectively melted much of the accumulated snowpack below 7,000 feet in elevation and also produced heavy rainfall even up to 10,000 feet, preventing significant snowpack accumulation, or rainfall absorption, even at those higher elevations,” wrote Gary Horton, a water planning economist who compiled the final report on the flood for the Nevada Division of Water Resources.

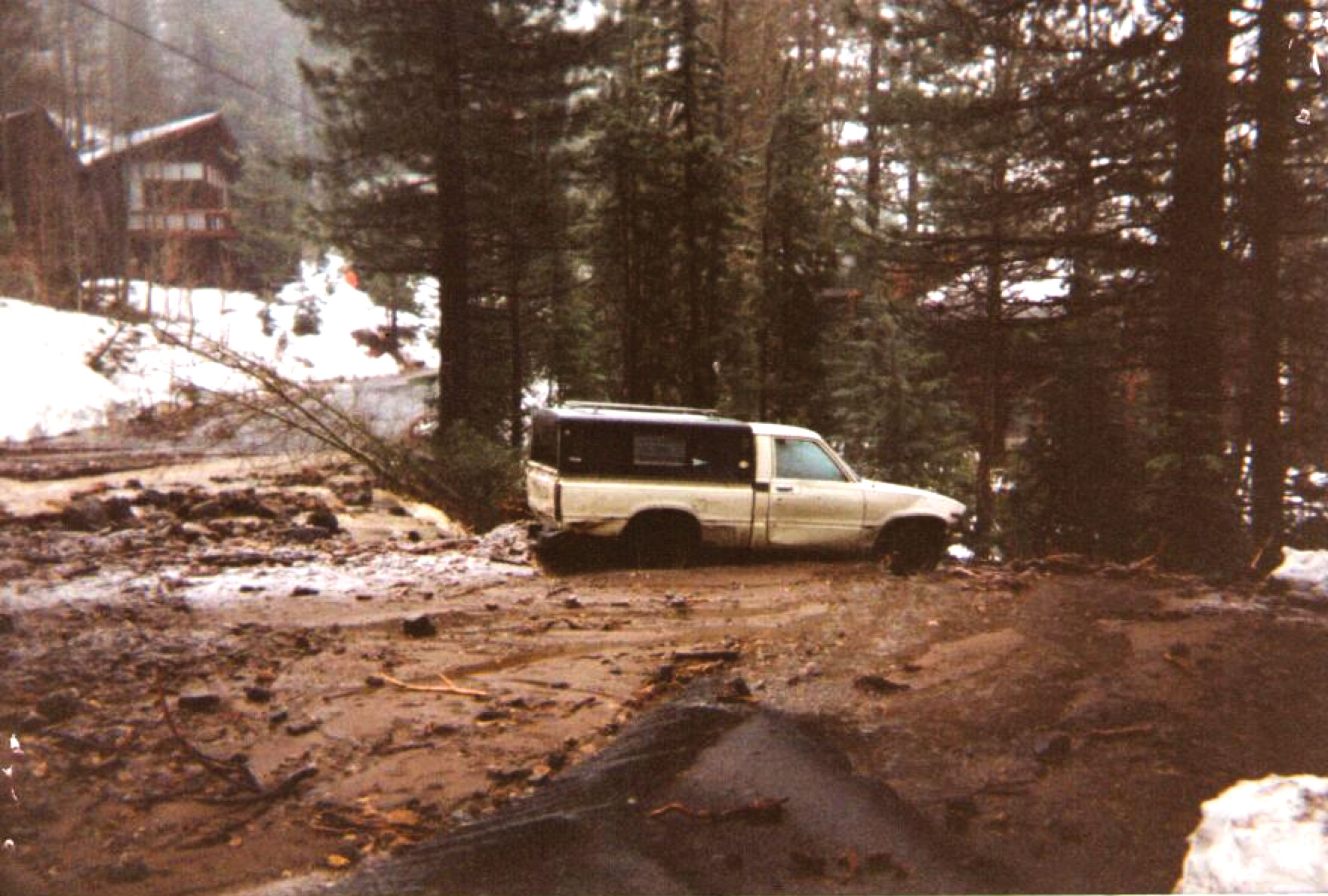

Squaw Valley neighborhood, January 2, 1997, photo courtesy John Read

A swollen Truckee River rips past the River Ranch Lodge during the Flood of 1997, photo courtesy River Ranch Lodge

Rising Danger

Paul Honeywell was fairly new to the United States Geological Survey (USGS) in 1996. He remembers being at a friend’s house along the Truckee River at a New Year’s party.

“A few of us at the party were wondering about how high the water was going to get. Soon after, I decided that since I had to work the next day, I should get across the bridge before I couldn’t,” Honeywell says.

Truckee Town Manager Tony Lashbrook was the community development director at the time. He remembers the rain falling soon after Christmas and not stopping.

“Our kids were pretty young so we spent New Year’s at home,” he says. “New Year’s Day I wanted to take a look around. We lived at Tahoe Donner at the time and when I drove down to Donner Pass Road it was a lake. The road was under water and it was inches deep.”

In Reno, where the Truckee River slices through the downtown corridor, flanked by the towering casinos and their neon glow, the conditions were worsening and officials were beginning to fret.

Kirkland’s wife, Cindy Kirkland, was the public information officer for the Nevada National Guard, and his son was a helicopter pilot for the Guard.

“We began some initial response, but when it hit us we were all quite surprised,” Kirkland says. “The river was completely out of control.”

Downtown Reno during the 1997 flood, photo courtesy City of Reno

Floodgates Open

Honeywell woke up New Year’s Day and began to hustle. As a hydrological technician, his basic job responsibilities entail measuring the flow at various points along the Truckee River and reporting back to the USGS water master, who controls the flow of the river by restricting how much water is released from Lake Tahoe.

Honeywell remembers that water was racing out of Lake Tahoe at about 2,200 cubic feet per second. The rain was so heavy that Tahoe had filled up and was overflowing, meaning the Truckee River was being fed more water than it could handle.

“When I first started, the rim at Lake Tahoe was a record low,” Honeywell says. “I thought I would never see it at its natural rim, but you flip a switch and its full and then overfull.”

Kirkland remembers it similarly.

“Tahoe was down six feet below its rim,” he says. “Officials said it was going to take 50 years to fill it. Well, all it took was one storm.”

Nearly 136,000 acre-feet of water ran into Lake Tahoe over the course of the storm—approximately one-third of its entire average annual filling in a single week.

It wasn’t only Lake Tahoe and the Truckee that overflowed.

Honeywell remembers the violence of Blackwood Creek, as many of the 63 tributaries that feed Lake Tahoe exceeded their banks and tore new paths through the landscape.

“Blackwood Creek historically is braided as it runs toward The Lake, but the flood just forced it into one area and when it came through it went anywhere it wanted,” Honeywell says. “Highway 89 was just a huge puddle and there was so much sediment left over after it recessed.”

Lashbrook remembers standing in downtown Truckee, watching propane tanks float by in the turbulent waters.

“I think what was amazing about downtown is that all the historical homes weren’t flooded,” he says. “They were smarter back then.”

But while the Victorian palaces of yesteryear remained unscathed, the Truckee River, Donner Creek and other creeks in the watershed were leaving wide swaths of devastation in their wake.

Truckee’s West River Street washed out, with half of the road simply vanishing. Flood walls were ripped out, several business in proximity to the Truckee River washed away and the Shell station at Highway 89 near Donner Creek was completely inundated.

“It’s safe to say I saw people whitewater kayak through the gas pumps at the Shell Station,” Lashbrook says.

It should come as no surprise, given the concentration of outdoor athletes, adrenaline aficionados and daredevils in the Truckee–Tahoe area, that one of Lashbrook’s most indelible memories of the flood was kayakers putting in around Donner Creek, eager to navigate the muddy brown rage of the deluge.

In Reno, Kirkland also had to deal with the occasional wild man attempting to tame the torrents, or crowds that gathered downtown on New Year’s Day to witness the spectacle of the mad waters carrying pieces of houses, entire cars and parts of the forest away.

By New Year’s Eve, the Truckee River was flowing at 18,400 cubic feet per second. The river was 17 feet high, five feet above flood stage.

Donner Creek at Highway 89, January 2, 1997, photo courtesy US Geological Survey

Assessing the Damage

Kirkland recalls surveying the damage in a helicopter piloted by his son as they flew over Reno on the cusp of the new year.

“As the light was going down you could see it was still roaring, this ugly monstrous river that transformed from the little trickle our Truckee River usually is,” he says. “It was picking up cars and I could see pieces of houses being inundated and pulled into it.”

By the next day, Reno was declared a federal emergency. Interstate 80 at the California–Nevada border was closed in both directions as a major landslide spilled onto the highway.

Reno–Tahoe International Airport was under about four feet of water and was closed indefinitely, meaning thousands of revelers who flew in for the holiday were stranded.

Meteorologist Jeff Hardin appeared on a local television station and said, “The problem is we have heavy rains in the Sierra and no storage capacity in our reservoir. The river is locked into the Sierra pattern and there is not much we can do about that.”

Then-Nevada Governor Bob Miller flew into Reno, landing at Stead Air Force Base on the outskirts of town. The National Guard was deployed and attempted to fill an order for nearly a half-million sandbags, which were promptly flown into Stead.

“It was pretty amazing, there was just stretched resources for everyone, including the National Guard,” says Cindy, Kirkland’s wife.

Part of the problem was a dearth of personnel, as several guardsmen were out enjoying the holiday during the apex of the flood.

“It was just a helpless feeling,” Kirkland says. “You were not going to beat that thing. If you tried too hard to put sandbags at the edge you’d end up in it.”

Kirkland recalls flying in the helicopter New Year’s Day and, after seeing the extent of the waters, ordering troops to desist in piling sandbags near the water and instead retreat to high ground.

The Tahoe Reno Industrial Center in Sparks became a lake. Hundreds of acres of warehouses, oil tanks and other assorted industrial operations were submerged for a full day.

“A lot of businesses were lost and the warehousing took a terrible beating,” Kirkland says.

Even downtown casinos were not immune, as four of the major 12 in the downtown corridor shuttered their doors, while many of the casinos closest to the Truckee River had about five feet of water in their first floors.

On the morning of New Year’s Day, a 52-year-old man was driving eastbound on the south side of the river. It was dark and he swung into the parking lot where his small business was located.

Speculation is that he was attempting to salvage what he could, but the road disappeared and his truck, his business and his life were carried away in the deluge.

Surprisingly, there were not a high number of fatalities, as only one other death was reported, in Gardnerville. That man, 59 years old, was operating a front loader in an attempt to bolster the river bank along the East Fork of the Carson River and was swept away.

While the loss of life was limited, the property damage was massive. All told, $1 billion in damage occurred in the Eastern Sierra and Northern Nevada.

By the time the floodwaters receded and the sun came out on Friday, January 4, most of the trapped tourists had repaired back to their communities as locals began to clean up and assess the extent of damage.

Squaw Valley neighborhood, January 2, 1997, photo courtesy John Read

Looking Back

By most metrics, the 1997 flood, which saw an estimated 63,800 acres flooded, was not as devastating as the 1955 flood that hit the Sierra and flooded Reno and Sparks. But the Nevada Division of Water Resources attributes that to the three additional dams along the Truckee River that were constructed as a direct result of the 1955 event.

While flows did not reach their record high along the Truckee, many believe that the incident was a once-every-200-year precipitation event. Unlike the highly regulated Truckee, the rivers and tributaries in the Walker River Watershed and Carson River Watershed all experienced record flows during the weeklong storm.

For the people who lost homes, cars and businesses, and saw their property destroyed, records and statistics are ancillary and whether the flood qualifies as the all-time worst is academic.

But the fact is, some people do believe it was the region’s worst natural disaster in modern times.

“It was a big deal,” says Lashbrook.

For the authors of the Nevada Division of Water Resources final report, they, too, stopped short of pronouncing it as the worst flood ever in the area, but in no way did that undermine its devastating effects.

“While perhaps not the worst flood of record in all waterbasins and along all river reaches, this event will certainly be remembered for its severity, its suddenness, its brevity and the widespread damage and socioeconomic disruption it produced throughout the watersheds of western Nevada,” the report reads. “The impacts of ‘The Flood of 1997’ will necessitate considerable assessment, reassessment and additional planning and mitigation to preclude or minimize future such events.”

Matthew Renda is a Santa Cruz–based writer.

1 Comment