24 Jun Sierra Stewards

From its modest start in the early 1990s, the Truckee Donner Land Trust has grown to become a significant force for conservation

In a nondescript clearing surrounded by a ring of lodgepole pines stands a monument to the humble origins of a conservation powerhouse.

The tucked-away sign—often passed without notice by climbers, runners, mountain bikers and campers—memorializes the initial conservation victory of the nascent Truckee Donner Land Trust, a 160-acre land purchase in the early 1990s that significantly expanded Donner Memorial State Park. For an organization that now regularly closes multi-million-dollar conservation purchases, the donor list on the sign—starting at $500 donations and topping out at $5,000 “leaders”—is a trip down memory lane, a reminder of the grassroots community grit at the foundation of the now remarkably successful organization.

Truckee Donner Land Trust staff, courtesy photo

The sign’s location is equally fitting. It stands at the intersection of world-class recreation, rich history and fertile habitat, three things that are still at the core of the Land Trust’s identity nearly 30 years later.

Today, just steps away from the clearing, rock climbers scale the rippled granite of Split Rock, a popular bouldering test piece, and campers spread out tents in Donner Memorial State Park’s campground. More than 150 years ago, pioneer wagon trains rolled over this land on their westward migration on one of the most important travel routes in the entire West—the Emigrant Trail.

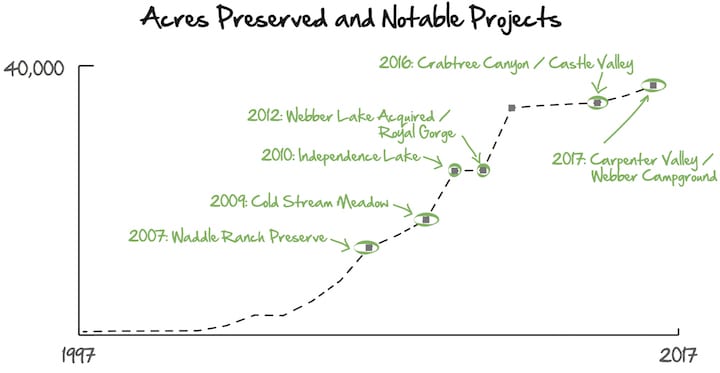

From those early days in 1990 when the idea of the Land Trust was discussed around a fireplace at John and Elizabeth Eaton’s home, and then a dining room table of other early members at Donner Lake, the organization has grown to protect tens of thousands of acres of land and piece back together a landscape fragmented by early railroad land ownership patterns. But the Land Trust has also taken on challenges that most other organizations would have shied away from—owning and operating a campground at Webber Lake, retaining grazing leases on protected land, purchasing the property that houses North America’s largest cross-country ski resort, and building miles and miles of premium Sierra singletrack.

Carpenter Valley from above, photo by Greyson Howard, courtesy Truckee Donner Land Trust

It’s safe to say that in the world of land trusts, the Truckee Donner Land Trust is utterly unique. One day, the staff may be envisioning a new backcountry hut system stretching into the corrugated peaks and valleys north of Truckee. The next day, they might be etching new singletrack trail into the ground around Donner Lake. And the day after that, they might be dealing with campground logistics or grazing leases at Webber Lake.

It requires vision to take on conservation projects like these—complex land deals that could be seen as deal-breaking headaches by more traditional organizations. But for the Truckee Donner Land Trust, these complicated deals that deliver biological, recreational and historical preservation to the region have become their identifying accomplishments.

“They see potential and they see opportunity,” says Markley Bavinger, project manager for the Trust for Public Land, a frequent partner of the Land Trust. “They aren’t afraid.”

Van Norden meadow on Donner Summit, photo by Bill Stevenson, courtesy Truckee Donner Land Trust

Linking Together the Landscape

When the Land Trust was young in the early 1990s, the overriding goal was to protect land around Donner Memorial State Park threatened by logging. But that vision quickly grew to the wide, fragmented landscape that surrounded Truckee.

Perry Norris, executive director of the Land Trust, first started working part time at the organization in the mid-1990s, and remembers some of the unique conservation work the organization cut its teeth on.

Perry Norris, courtesy photo

One project was working with the Nevada County Land Trust (now the Bear Yuba Land Trust) on protecting habitat for the pitcher plant, a strange, carnivorous plant whose southernmost range includes bog-like wetlands in Nevada County.

The organization was working on small budgets, the energy of passionate volunteers and big ideas.

“It was kind of like a dog chasing its tail. We were just trying to get enough operating money to survive and the idea of raising huge amounts of capital to deliver on our mission was really distant,” says Norris. “But in those early years, for a volunteer shop with a half-time executive director, they got a lot done.”

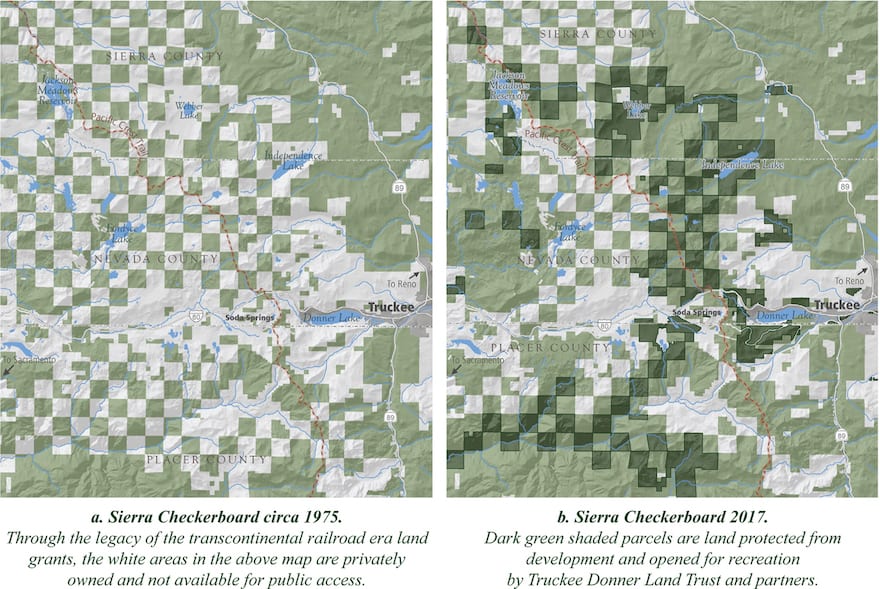

The vision of the organization soon broadened to a project that was remarkably ambitious—one overarching objective that would consume the Land Trust for decades. It began eyeing the checkerboard of alternating public and private land that dotted the central and northern Sierra, a product of railroad land grants, and imagined the possibility of reassembling large tracts of rich habitat and recreation-ready land.

“When I think about Perry, he is just a risk-taker and so is the Land Trust. You can’t do this work and have that scale of impact without being bold,” says Dave Sutton, program director with the Trust for Public Lands, who was a leader in the Sierra Checkerboard campaign.

In those early years the Land Trust’s board did an exercise where they outlined $100 million in real estate deals they wanted to complete over the long-term, says Norris. He remembers almost laughing at the seemingly impossible task for such a small organization. They took out markers and highlighted tens of millions of dollars of property in yellow—a wild conservation wish list.

“And by golly if we didn’t buy 90 percent of it,” says Norris.

“And by golly if we didn’t buy 90 percent of it,” says Norris.

Because of this ambitious vision, the landscape encircling Truckee looks dramatically different today. As golf course developments and resort neighborhoods sprouted up around Truckee in the 2000s, the organization was busy buying up huge tracts of land for conservation everywhere from the Martis Valley to Sierra County.

“The pace of development starting in 2000 was kind of an ‘aha’ moment for the community,” says Norris. “We put a lot of effort into unincorporated areas of Nevada and Sierra counties because we thought that was the next wave, and most of those tracts of land are now preserved.”

These include biological treasures like Carpenter Valley and Perazzo Meadows, historical gems like Webber Lake, and recreational hotspots like Royal Gorge, Independence Lake and Johnson Canyon.

It’s hard to imagine, but rewind the clock a couple decades and then run it forward again in a world without the Land Trust. The region would inarguably look vastly different. Homes would likely dot the land off of Highway 267 in the Martis Valley, Royal Gorge might house a large resort development, and the vast swath of mostly intact habitat north of Truckee would likely be populated by large-lot homes.

“That is why we launched the Sierra checkerboard. Those lots we thought were protected, weren’t protected,” says Sutton of the land north of Truckee.

Frog Lake Cliffs reflect in the still water of Frog Lake, photo by Bill Stevenson, courtesy Truckee Donner Land Trust

Conservation Through Capitalism

Waddle Ranch Preserve, photo by Elizabeth Carmel, courtesy Truckee Donner Land Trust

The Land Trust’s conservation method, of only working with willing sellers, makes it a pragmatic, and not political, organization. On any given day, the organization could be meeting with a ranching family, a multi-generational landowner, or, as in the case of Waddle Ranch, one of the richest and most influential families in the nation on potential land acquisitions.

“These are people with deep, deep emotional connections to these properties, so the opportunity to sell it to an organization that will take care if it for all of eternity is very appealing,” says Jeff Brown, president of the Land Trust’s board of directors.

This pragmatism has allowed it to work quickly and effectively whenever prime property becomes available.

“Land trusts in general are very successful land conservation organizations because they are pragmatic and not driven by ideology. In essence, it is conservation through capitalism,” says Norris.

“We’re wildly opportunistic,” adds Norris, and then, reflecting on the organization’s more than 36,000 acres preserved: “We’ve been unbelievably lucky.”

While Norris calls it luck, others recognize the immense amount of work it takes to preserve tens of thousands of acres of prime Sierra Nevada land.

“They are nimble and responsive and incredibly hard-working,” says Bavinger of the Land Trust staff. “And they just get it done.”

Momentum from Martis

The preservation of Waddle Ranch, a 1,462-acre tract of land zoned for resort development in the Martis Valley, was a turning point for the organization. It proved that the Land Trust could execute complicated land deals and marshal enough community support in funding to close such an expensive land transaction. The property sold to the Land Trust for $23.5 million in 2007 and was later conveyed to the Truckee Tahoe Airport District.

Steam rises from Webber Lake, photo by John Peltier, courtesy Truckee Donner Land Trust

“If we hadn’t done Waddle, I don’t know if we would have done Webber,” says Norris of the ensuing purchase of Webber Lake, a beautiful trophy fishing lake and meadow system.

Working off the reputation of projects like Waddle Ranch, Webber Lake and Royal Gorge, the Land Trust continued apace, launching large conservation projects like Frog Lake and Carpenter Ridge, an ongoing conservation campaign, and the Poulsen property in the Squaw Valley meadow.

With all of this conservation activity comes increased demands on Land Trust staff. Forestry work, trail building and campground management have all become a big part of the workload of the small land trust. But it does it with a small, dedicated, hard-working team.

“We’re still lean and mean and scrappy,” says John Svahn, associate director of the Land Trust.

But it doesn’t do it alone. Valuable partners like the Trust for Public Land, Sierra Nevada Conservancy, Truckee River Watershed Council and many other regional organizations work together on these important transactions. And legions of donors, both large and small, keep the conservation and maintenance price tags attainable.

“We are getting to the point where it costs a lot of money to buy these properties, but the underappreciated part is how much it costs to manage these lands,” says Brown.

Perazzo Meadows from above, photo by Greyson Howard, courtesy Truckee Donner Land Trust

Many of the Truckee Donner Land Trust’s conservation victories could be seen as visionary—as if the organization foresaw the development pressures that would push out from Truckee and into the land north of it. And much of that is true. But conservationists say the work has come just ahead of the development pressures pushing behind them.

“I think the work we have done and are doing is just-in-time work. I hope we can stay ahead of the curve,” says Bavinger. “A lot of rural places are emptying out, but Truckee is one of those places where people are going to. We got there just in time to have the vision to get ahead of that pressure.”

Now, the Land Trust and others will deal with new opportunities and challenges, specifically the threats of catastrophic wildfire and climate change, says Sutton.

“We have to rethink what it means to conserve property. We’ll lose the habitat and the beauty of our natural lands if the Land Trust community does not embrace this new responsibility of stewarding and restoring these natural lands,” says Sutton.

For an organization that prides itself on being both bold and inventive, these new climate and forestry challenges are nothing to shy away from.

“Perry doesn’t have a formula. He is not locked into a formula that we do this kind of deal and don’t do that kind of deal. He is willing to break the mold,” says Brown.

That appetite for new challenges, and an overwhelming optimism about what can be accomplished in the name of conservation, is the driving force that has made so many wild conservation goals a reality over the years.

“The glass is always half full at the Truckee Donner Land Trust,” says Norris.

David Bunker is Truckee-based writer and editor.

No Comments