27 Sep The Boom and Bust of Ski Ballet

Flamboyant style and innovation defined ski ballet until the sport flamed out in an explosion of tassels, synth pop and spandex

Bob Howard had been benched. Again. For five games in a row, the college football coach had stared hard at the lanky running back from Hug High School and jerked a thumb at the sidelines. What am I doing here? Howard thought, pacing down Mendocino Avenue hours later. He was so steamed he almost blew right past the poster hanging in the window of the local ski shop—of a skier joyfully frozen in mid-flight, sporting bright yellow ski boots.

In the early 1970s, few people owned ski boots any color other than grim black. The boots were a new model, hot off Nordica’s assembly line, unofficially called “the Banana” and about to sell 400,000 pairs to a bunch of disaffected, long-haired kids who were sick of their parents’ skiing.

The $300 that Santa Rosa Junior College had just given Howard in scholarship money began to itch in his pocket.

An hour later, Howard leaped into his Datsun pickup, banana boots in hand, and sped off. He had almost made it out of town when he stopped to call his mother in Reno on a payphone. He told her his plan.

“Don’t stop,” she said. “Your father will kill you. Just keep going.”

Howard, who grew up skiing at Sky Tavern near Reno, was about to dive headfirst into the blossoming sport of freestyle skiing, or “hotdogging.”

Freestyle skiing emerged in the 1960s and grew into the ’70s, led by pioneers such as Wayne Wong who brought innovative tricks and a flashy style to the snow. Early competitions combined elements of moguls, aerials and ballet as skiers ripped down natural mogul fields, spinning and flipping off of bumps while incorporating the technical maneuvers that would become ski ballet. As the sport gained traction, it eventually branched into the three specific disciplines.

Howard trained his focus on ski ballet, watching over it as it rose to prominence—and then as it fell from the spotlight and eventually faded into near-obscurity. As a legitimate sport, it’s been dead for nearly 20 years, relegated to the occasional mini-trend on Twitter or live showcase by the few former athletes who remember it.

What made ski ballet unique—the artistry, the clownishness—were ultimately what doomed it. Yet, the niche discipline lives on despite its obscurity, resurrected by an older generation’s unflagging passion and a newer generation’s brimming curiosity.

Howard sports an Astraltune personal stereo player during the filming of an advertisement, courtesy photo

Ballet Boom

Today, Howard has close-cropped, spiked silver hair and open, almost mischievous features, which light up as he turns the leaves of his ski ballet clippings.

“There was nothing cooler,” he says as he flips through the pages, lingering over an action sequence spread of the “Howard Around,” his signature move.

In the early 1970s, there were no journalists knocking down his door, clamoring for interviews for Ski Magazine. A long-haired college dropout, Howard drove around the country, training at mountains with forged ski passes and competing in hotdogging competitions. He slept at odd angles and hours in his pickup, nicknamed “the Sixpack Motel.”

Though he started out skiing combined, or all three freestyle disciplines, it became increasingly clear that ballet was Howard’s to own. The sport was exciting, creative, fresh—and wasn’t self-serious, which meant pulling a previously unseen trick out of his arsenal in competition and amazing the audience wasn’t uncommon.

“We were inventing new stuff almost weekly,” says Howard, who—with an early-model Walkman strapped to his chest—would practice his vaults and spins at Reno’s Rancho San Rafael Park.

Howard’s friend, Dan Schindler, a top-ranked ballet skier, would hear rumors that Howard was “out in the trees” working on new tricks. In 1979, Howard executed one of the first 720-degree spins in competition. “And, you know, $10,000 and a Chevy later, he’s on his way,” says Schindler.

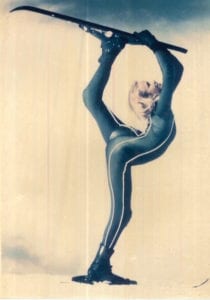

Suzy Chaffee performs her signature move, the Suzy Contortion Spin, courtesy photo

Some freestyle skiers, like Suzy Chaffee, had a different idea of how ski ballet should look. She first pushed for ballet to be choreographed to music in 1971, and, until it caught on a year later, was the only skier who competed this way.

The former Olympic alpine racer, model and actress—known from her commercial appearances as “Suzy Chapstick”—had fallen in love with ski ballet after retiring from alpine racing in the late 1960s. In competition, she leaned into the idea of the sport as an art, as pioneered by Alan Schoenberger, a World Cup ballet medalist who was known for painting his face and performing mime acts on skis. Chaffee saw ski ballet as a way of dancing down mountains.

Seeking a masculine-feminine balance for the sport, she visited dance studios and took ice-skating lessons. That was the reason she was one of the only skiers who could perform a “Suzy Contortion Spin,” lifting one leg up behind and over her head, grabbing her ski, and spinning in place. Audiences and judges loved it.

Her literal leg-up over the competition got under the skin of the competitors who favored the more traditional tricks over the dance movements. Some complained publicly about where an emphasis on the newer dance elements, which were often accompanied by makeup and costumes, would take the sport.

The Reno Contingent

While Chaffee rode her smooth dance moves to stardom, an up-and-coming ballet skier from Reno named Lane Spina preferred the more athletically demanding side of the discipline. One of his signature moves was the pole flip, where a skier plants his or her poles in the snow and then launches into an airborne flip, sometimes adding a twist or two.

“It’s an amazing feeling—a combination of pole vaulting and acrobatics,” says Spina. “When you do your first one, you’re hooked.”

In 1976, at age 14, Spina got a job working in a ski shop in Reno called Aspen Sports. The storefront was small but opened up in the back to become a midsized warehouse. The shop manager filled the space with a ski deck—a 40-by-30-foot angled conveyor belt of carpet designed to mimic the feel of a real slope, hoping to draw in skiers during the offseason.

That’s how Spina met Bob Howard, who was among a group of well-known freestyle skiers who used the shop’s deck for training.

Yale Spina, Lane’s older brother and professional freestyle competitor, was also an employee at Aspen Sports and trained there often, along with others such as John Clendenin, Ellen Post, Troy Caldwell and Chris Blanton.

The dozen or so Reno skiers who frequented the shop came together as an informal team. Howard calls the group “the Reno contingent.” In winters, they trained and competed together at Squaw Valley and Heavenly. Lane Spina watched and learned—and it paid off, as he went on to win his first World Cup event in 1984.

He credits that win, at least partially, to a pair of lucky pants owned by Howard.

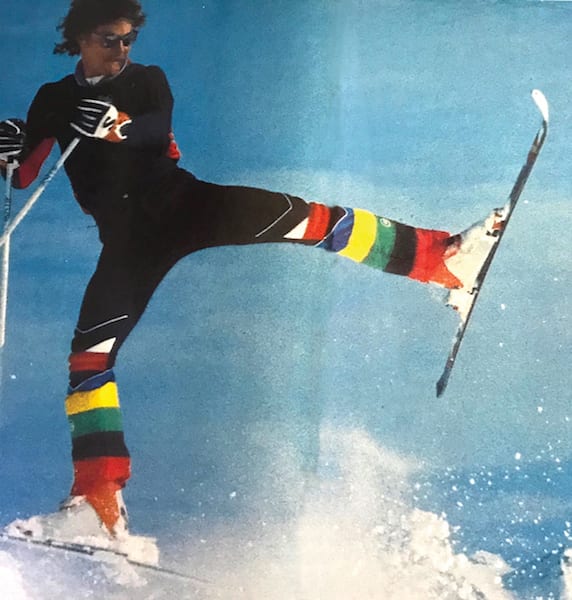

Bob Howard wears his lucky pants while promoting a summer camp at Les Deux Alpes, France, courtesy photo

The pants, which featured horizontal rainbow stripes below the knees, were instantly recognizable by World Cup competitors—particularly a couple of Germans, Hermann Reitberger and Richard Schabl, who had competed against Howard in the past.

“Seeing the look on their faces when I showed up in those pants was classic,” says Spina. “When I won that first event of the season, they both pointed at the pants, shaking their heads.”

That wasn’t the only thing Howard passed on.

Spina credits his early success to specific instructions given by Howard on how to manage competition-day activities. “He explained everything that was going to happen, and why, during that critical day, so when I got to the World Cup, I just ran the strategy,” says Spina.

Other advice, like resting a full day before competition, came from his father Charles Spina, a former semi-pro baseball player and coach. Equipment advice came from his brother Yale, a ski technician who taught about the benefits of having the right equipment, including a special set of competition-only skis that only came out of the ski bag for contests.

“My add was to train on heavier ski equipment, so that skiing with lighter equipment made you feel like Superman on [competition] day,” Spina says.

Starting on the World Cup circuit in 1984, Spina competed in the combined category—moguls, aerials and ballet (also known as acrobatics by this time)—before tearing his anterior cruciate ligament and returning as a ballet skier to focus on his strengths in pole flipping.

Lane Spina demonstrates the dynamic motion of a pole flip in a 1989 photo shoot at Squaw Valley, courtesy photo

Howard performs in the Labatt’s pro freestyle tour at Mont-Sainte-Anne, Quebec, courtesy photo

Evolving Sport

By the early 1980s, freestyle skiing had organized and was lobbying the International Olympic Committee (IOC) for inclusion in the Winter Games. Meanwhile, ski ballet debuted as a World Cup event in 1980. Howard won all five World Cup contests that season and eight of the nine events the following year.

While competing at the highest level of the sport, Howard decided to take the show on the road as well. In between teaching a freestyle skiing camp at Les Deux Alpes, France, and competing, he called up an old friend of his, a guy named Phil Sifferman, who worked for Volvo organizing traveling ski shows around Europe. Howard thought he could choreograph a new show for Volvo that took the already flashy nature of the performances even further.

“Phil,” he said, “you know the Harlem Globetrotters?” From then on, says Howard, “It was just no-holds-barred.”

With the Volvo Ski Show he helped put together, rock ‘n’ roll music pounded in the ears of 10,000 spectators as freestyle athletes performed their most crowd-pleasing tricks—giant daffys, spins and flips off jumps, with ballet maneuvers thrown in the mix. Howard watched hours of MTV and Fred Astaire movies, jotting down choreography ideas.

Outside of this world of entertainment, however, the sport was struggling with its identity, both in the direction it was headed—the more traditional, trick-oriented version or the one defined by the Chaffee-style dance routines—and whether to give up its professional status in order to become eligible for the Olympics.

Olympic Bust

After years of lobbying to become an Olympic sport, all three freestyle disciplines were included as demonstration events in the 1988 Calgary Games.

Lane Spina during a summer training camp at Mount Hood, Oregon, courtesy photo

The ski ballet was an explosion of tasseled sleeves, synthesized pop and flame-embroidered spandex. Spina, who skied with a torn ligament, earned the silver medal while Reitberger of Germany won gold.

Ski ballet was a demonstration event again in the 1992 Albertville Games, where Spina earned bronze as Reitberger again danced his way to victory. Spina says a new scoring system awarded points for dance moves between large tricks—his specialty—which allowed skiers with limited trick capability to score high enough to win medals.

“This led to a much more watered-down experience for the spectators, much like a comparison from gymnastic floor routine to rhythmic gymnastics, where big tricks are not required to win,” says Spina.

While moguls debuted as an official Olympic sport that year, and aerials followed in 1994, ballet was dropped by the IOC. The once-popular freestyle discipline never regained its momentum, and eventually faded from the competitive scene by the new millennium.

Those involved in the sport blame a number of factors for its demise, from the increasing emphasis on choreographed dance routines over the more difficult tricks, to never figuring out how to market the sport to the average skiing audience.

Spina believes that if the sport’s leadership would have pulled back to the elements that launched ballet in the first place, the tricks, the judging issue would have been resolved and the sport would still be in the Olympic today—“with great TV ratings,” adds Spina, who pursued another career, earning a mechanical engineering degree and MBA from University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Howard says ski ballet simply lost its flare. “There’s a point in life where something that you think is really cool, you know, it’s no longer cool. It’s like a sociological turnoff.”

Still Performing

While no longer a competitive sport, ski ballet still exists, in a warped way, on the Internet. Twitter and YouTube users delight over clips of pole twirling and dance moves that more resemble figure skating than skiing.

“They just show the silly stuff, and people go, ‘This is a sport?’” Howard laments. “They don’t know… it’s one of the most difficult things, aerobically, to do.”

Though he no longer attempts the technical tricks, Howard can still ballet ski with a graceful style and panache reminiscent of his former self. To prove as much, he performed a ski ballet pairs routine with Chaffee at Squaw Valley in April 2018 as part of the U.S. Ski & Snowboard Hall of Fame induction ceremony. Howard has undergone two knees replacements and Chaffee two hip replacements.

“I was thinking, ‘If one of us falls, we’re never going to be able to stand up again. We’re going to be so screwed.’ And we were just laughing,” says Howard.

“It was like we time-warped back to the seventies,” says Chaffee.

The atmosphere that day at Squaw was light and relaxed. There were silly costumes. People were feeding off each other, not caring if they fell.

“Ballet didn’t die,” says 1998 Olympic gold medalist mogul skier Jonny Moseley, who was at Squaw that day as well. Moseley, who learned the art of ballet while coming up through the Squaw Valley Freestyle Team in the 1980s, was decked out in a blue and white onesie with rainbow stripes across the chest, performing ballet tricks alongside legendary freestylers like Bob Legasa, Dan Herby (Squirrel Murphy’s stunt double in Hot Dog… The Movie) and “Airborne” Eddie Ferguson, all in their 50s, 60s and 70s.

“Freestyle skiing is a moving target. It’s always going to be changing,” Moseley says. “It turned into slopestyle and rails and all that stuff.”

Recently, a documentary crew from Great Big Story came to Squaw Valley and filmed Howard and Moseley teaching a group of kids some classic ski ballet moves (see video below).

“It was funny because they got so into it,” Howard says. “They were like, ‘This is great! I wanna do this forever!’”

The old Reno contingent still gets together, shredding the local mountains in a pack of close friends, doing what they love. And still, the biggest trick of the day receives bragging rights among the group. But they can’t go back to Aspen Sports. The little shop where they once spent hours spinning and dancing on the ski deck is now a Domino’s Pizza.

AJ McDougall is a writer and researcher based out of Nevada and New York. She’s currently working toward an English degree at Columbia University, but comes home to Lake Tahoe whenever she can to ski and hike.

No Comments