27 Nov Squaw’s French Connection

Émile Allais was a pioneering ski visionary who set Squaw Valley on the path to greatness in its earliest years

Squaw Valley’s 70-year tradition of skiing excellence can be traced back to the influence of one man.

Yet, in the resort’s pantheon of all-time greats, the originator who set the foundation while bringing fame, prestige and world-class skiing to the newly christened slopes—and attracting others of similar ilk—receives little recognition seven decades later.

Perhaps it was Émile Allais’ quiet manner. Or his relatively short tenure as Squaw Valley’s first ski school director. Or it could simply be the sheer amount of time that has elapsed since the “father of modern skiing,” as Allais has been hailed, left his mark in Tahoe amid one of the most accomplished ski careers in history.

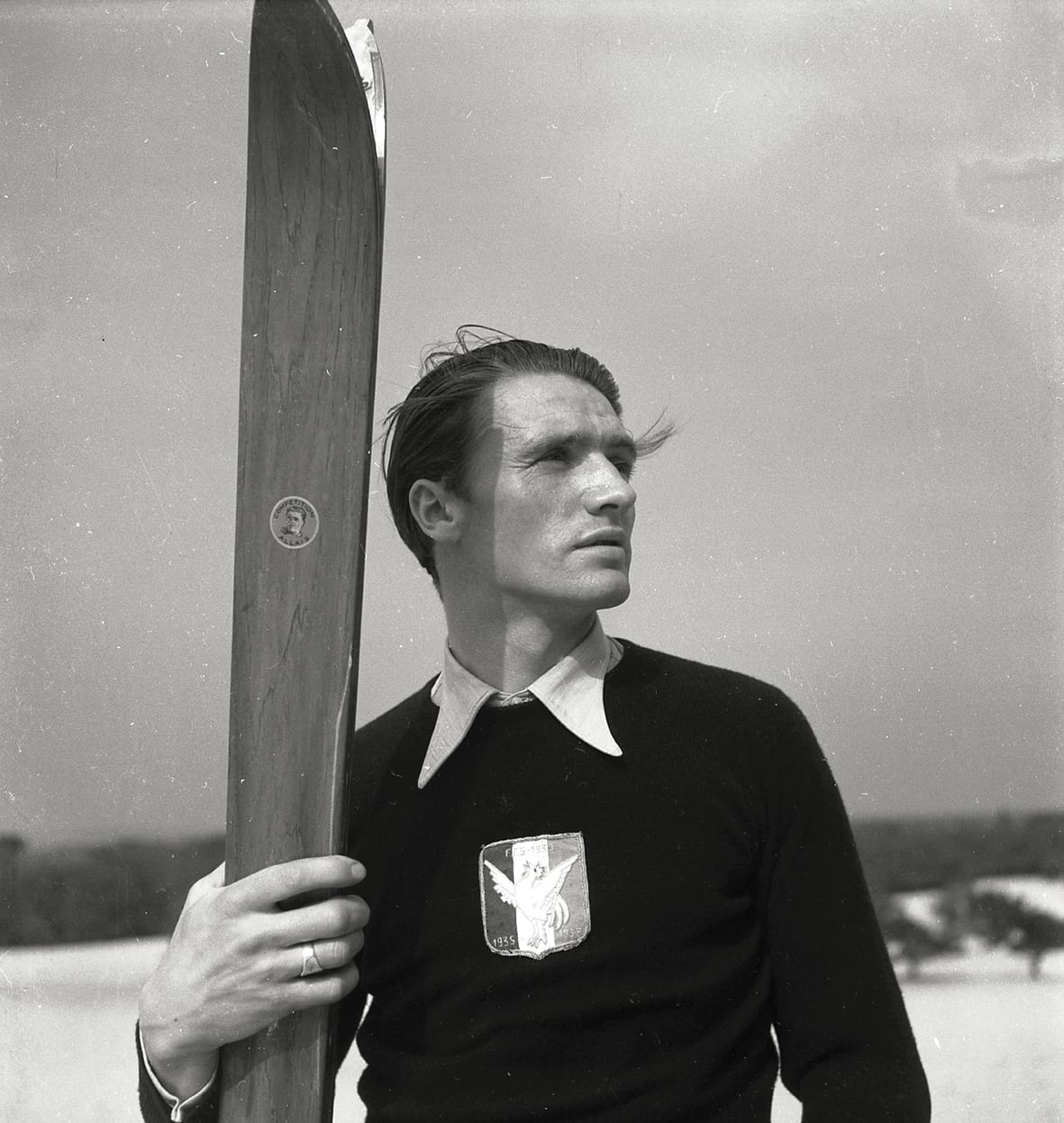

Émile Allais spent much of his post-racing career teaching the parallel skiing technique, and even co-authored two books that include photos of him demonstrating the method, photo by Pierre Boucher, from Allais, la légende d’Emile, courtesy Karen Allais-Pallandre

“In my view Émile Allais is underrated everywhere, because he was just one of those low-key people who liked to ski, and he wasn’t a promoter,” says Dick Dorworth, a Tahoe native and Hall of Fame ski racer who counts Allais among his childhood heroes. “In my circle there are people who are ski historians who don’t really know much about him, and it’s kind of sad. He’s one of the great influences in skiing. You can still see his style in modern skiers.”

In fact, it was Allais who brought the commonly accepted technique of today—skiing with planks parallel to one another—to the masses.

France’s first ski racing star, Allais co-authored a controversial book in 1937, Ski Francais, that challenged the established Arlberg snowplow method evolved by Austrian Hannes Schneider. After fighting on skis for the French underground in World War II, Allais went on to teach his parallel skiing technique at resorts around the world, including a promising startup in the Sierra Nevada.

But Allais’ contributions to skiing, and his subtle yet rippling impact at Squaw Valley, extend far beyond the French parallel method that he championed.

In addition to his ski racing stardom, Allais’ career included coaching stints with the Canadian, French and U.S. Olympic alpine teams; designing numerous ski resorts across France, Chile and North America; helping create progressive skis as a longtime consultant for Rossignol; and designing goggles, aerodynamic pants and boots that fastened to skis, among other innovations.

Allais was a pioneering big-mountain skier, as well, recording first descents down some of the most serious peaks in the Mont Blanc region of the Alps, his home range. A powder slayer years ahead of his time, he undoubtedly did the same at Squaw Valley, tapping into the resort’s most challenging untouched lines long before the legends who followed.

Squaw Valley’s first ski school at the start of the 1949-50 season included only five instructors: from left, Dodie Post, Émile Allais, Warren Miller, Charlie Cole and Alfred Hauser, courtesy photo

Shaping Squaw Valley

Allais first set eyes on Squaw Valley from the seat of a Weasel, a surplus 10th Mountain Division tracked vehicle used to access the roadless valley at the time. It was fall 1949. Demanding only the best for his new resort, Alex Cushing had reached out to Allais to direct Squaw Valley’s ski school, stealing his talents away from Sun Valley, Idaho.

According to a 2003 article in Skiing Heritage, shortly after Allais arrived at Squaw Valley, he “began to advise Cushing on the location of lifts and trails and was soon trekking the valley, placing flags to guide the workmen.” Word spread quickly that the great French champion was coming to California, and hopeful instructors from around the country, and beyond, sent resumes and made their way to Squaw Valley.

Squaw’s ski school was lean at the start of the first winter, with only four instructors working under Allais. They included a young Warren Miller, who taught for Allais at Sun Valley the previous winter; 1948 Olympic alpine racer Dodie Post (Gann) of Reno, who was among the few women ski instructors in the country; Charlie Cole; and Alfred Hauser. Miller filmed his first feature-length ski movie at Squaw that first winter, when Cushing paid $125 a month plus room and board.

Tyler Micelou joined Allais’ team later that winter, while Stan Tomlinson served on the ski patrol the first season before taking over the ski school when Allais left. Allais brought in other top-flight instructors as well, including Canadian Doug Pfeiffer and Jo Marillac, the French war hero and three-time Gestapo prisoner escapee who later helped Cushing secure the 1960 Winter Olympics.

“Everyone wanted to ski the new French method,” Post Gann, a 2001 inductee to the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame, told Skiing Heritage. “Émile’s ski school was very successful. And he was a lot of fun to work with. It was serious and you got your work done, but it was great on those days when he’d come up and say, ‘Let’s go skiing,’ which, of course, you did. Fast. And behind him. He was so good technically. And so charming…”

In addition to his alpine ski racing talents, Allais was an expert in off-piste terrain, photo from Allais, la légende d’Emile, courtesy Karen Allais-Pallandre

Leaving a Legacy

Dorworth was 11 years old when he skied Squaw Valley for the first time during its opening season. Having only been to the two small rope-tow resorts near his Zephyr Cove home—one along the road to Heavenly Valley and the other, White Hills, atop Spooner Summit—he was blown away by the scale of the new resort on the North Shore.

“When Squaw opened on Thanksgiving of 1949, my buddy John Robinson and I, we’d never even seen a chairlift, so we tried to get on the chairlift, and we were so spooked that I knocked John off the lift, and I rode up the whole way holding onto both sides,” Dorworth recalls.

His impressionable mind was blown once more that day when he first witnessed Allais ski.

“We had our local ski heroes, people we looked up to for their good skiing,” Dorworth says, “but Émile was there, and his skiing was so far above anything we had ever even thought of, it really changed my life as a young kid. I went, ‘Wow, there’s more to this than I had ever imagined.’ He was that good. So as a kid, I’d go over there and watch him every chance I got.”

Dorworth grew into a world-class speed skier—and mentor to fellow Tahoe speed skier Steve McKinney—and was the first person to break the 105-mile-per-hour barrier.

While Allais left Squaw Valley in 1952 after only his third season, heading to Southern California to help design Mount Baldy, he left an indelible mark during that short span.

One young Squaw Valley talent in particular benefitted from his serendipitous encounters with the French racing star. An 8-year-old Jimmie Heuga, whose father ran a lift at Squaw, followed Allais around the mountain daily, watching and learning from one of the best skiers in the world. Heuga became the first American man to earn an Olympic alpine medal in 1964 (along with Billy Kidd, who earned silver in the same slalom event).

Émile Allais pictured on his 100th birthday, February 25, 2012, with his 1937 racing skis and a new pair of Rossignols, photo by Sylvie Chappaz, courtesy Karen Allais-Pallandre

“Émile Allais had a great influence at Squaw Valley, especially by bringing in Jo Marillac later,” says Tom Kelly, the former longtime Squaw Valley and U.S. Ski Team coach. “Having the French Ski Team influence at Squaw Valley really developed a lot of these racers who come from Squaw Valley now. It got passed down from generation to generation.”

Formative Years

Allais was born in 1912 in the village of Megéve in the Mont Blanc region of the French Alps, where his parents owned a bakery. After his father was killed in World War I when Allais was 5, his mother remarried and the family bought a small hotel as Megéve grew into a popular ski destination. Allais left school at age 12 to apprentice in the family hotel and work other small jobs.

Around this time, Allais’ uncle, Hilaire Morand, worked as a mountain guide leading ski treks through the rugged terrain near Mont Blanc. Morand had a pair of skis built of ash for his nephew, who packed in supplies for his tours. Allais worked with his uncle for the next four years, sometimes skiing eight hours a day. The physically demanding work not only hardened the small and wiry teen, it helped Allais acquire balance and feel on the snowy terrain.

By the time Allais quit working for Morand at age 17, he had become an adept athlete who enjoyed playing hockey and excelled in cycling and cross-country ski racing. With the rise of competitive alpine skiing across Europe, Allais entered his first alpine ski race in 1931 at age 19.

He served his mandatory year of military service the following year and was recruited for his battalion’s alpine team, allowing him the opportunity to train and compete in military races during his service.

Allais had already been introduced to the parallel turn in his late teens by ski school instructors from Innsbruck, Austria, who did not subscribe to Hannes Schneider’s Arlberg method—initiating turns with skis angled inward in a V shape.

The instruction planted the seed that would lead to Allais’ adopted style. The parallel technique was further validated in Allais’ mind after he had the chance to study the best slalom racer in the world at the time, Austrian Toni Seelos, during Allais’ first season on the professional circuit in 1934.

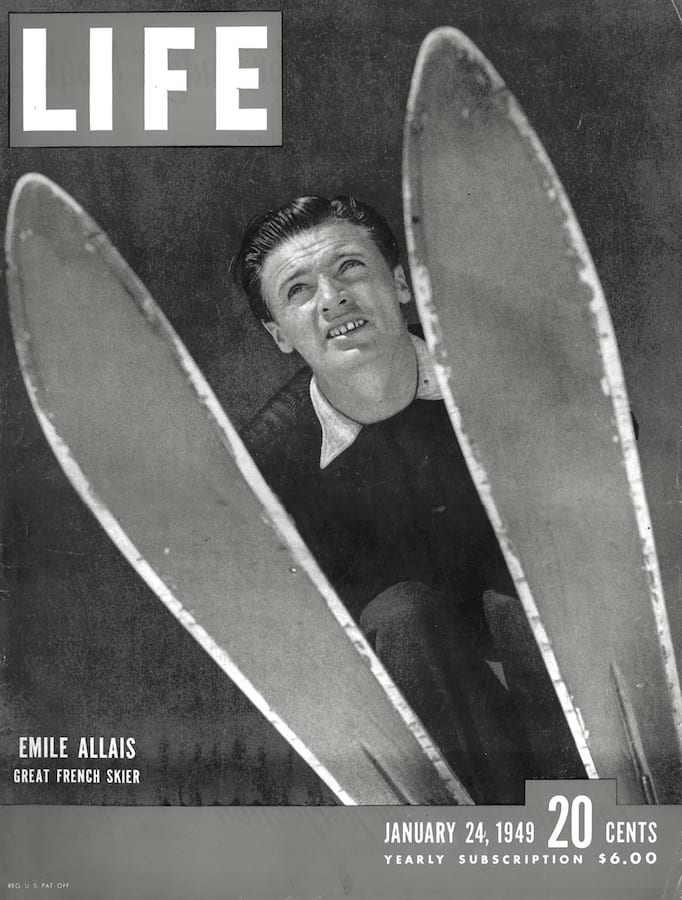

Allais on the cover of Life magazine in 1949, the year he accepted a job as Squaw Valley’s first ski school director, photo courtesy Karen Allais-Pallandre

French Champion

After steadily improving on his results, Allais recorded his first win in the combined event at Hahnenkamm in Kitzbühel in 1934, giving France its first victory in a major international race and alerting his competition that there was a new challenger on the circuit.

Allais carried his success into the 1935 season, the year he developed a new technology by drilling holes through his skis and fastening his heels to the bindings with leather straps. Although this “laniere” had been used by other racers, Allais moved it back in order to hold his instep down rather than just the ball of his foot. The subtle adjustment gave Allais significantly more ski control as he continued to climb the competitive ranks.

The opportunity to compete on a global stage came in 1936 when Germany hosted the Garmisch Olympic Games, where alpine events were scheduled for the first time. The International Olympic Committee decided to award just one set of alpine medals for the best combined score.

Germans Franz Pfür and Gustav Lantschner took gold and silver, respectively, while Allais earned France’s first Olympic medal with the bronze. He was a national ski hero. A photo from the award ceremony shows the two Germans proudly extending their right arms in Nazi salutes, and Allais to their left, staring straight ahead with his arms at his sides. Hitler congratulated him personally. “He looked harmless enough,” Allais said years later.

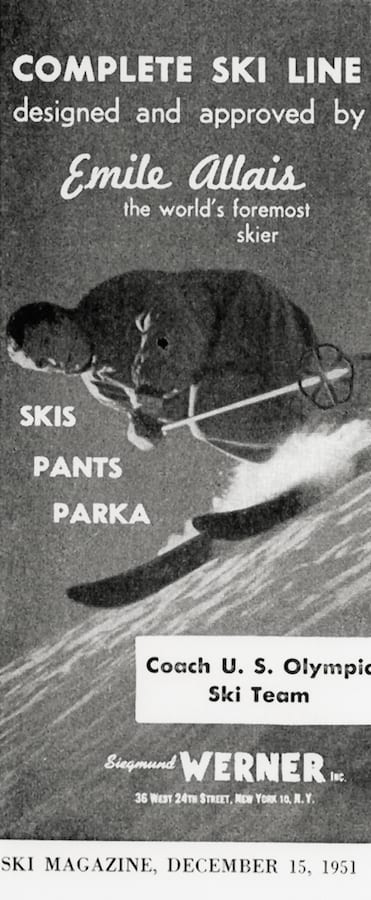

An advertisement in a 1951 Ski Magazine, photo courtesy Karen Allais-Pallandre

Allais enjoyed his most dominant stretch of alpine racing in 1937 and 1938, when he became the first man to hold the all-around world champion title in successive years.

In 1937 he co-authored the seminal Ski Francais (“Skiing the French Way”) with French teammate Paul Gignoux, which became one of the most popular and controversial sports books of the pre-war era and was translated into several languages, including Japanese (he co-authored a second book in 1947 that expanded on the first). The same year, he co-founded the Ecole du Ski Francais, the largest ski school in the world, and was selected to train the French FIS team, helping 17-year-old teammate James Couttet become the youngest world ski champion. To top off the busy year, he married his longtime sweetheart, Georgette.

Following another successful season in 1938, Allais’ ski racing career screeched to a halt in 1939 when he broke his ankle training for the FIS championships. Germany invaded Poland the next fall, igniting World War II and ending international skiing competition for seven years.

Post World War

Allais fought as a soldier and later a guerrilla in the Second World War, reportedly narrowly avoiding capture in Torino while guarding the Franco-Italian border with his countrymen.

He and Georgette left post-war France in 1946 after Allais received an offer to lead the ski school and direct the layout of a new resort, Val Cartier, near Quebec. The next spring he was contacted by the Chilean government to perform the same tasks at a developing resort in Portillo—starting a trend of sailing to the Southern Hemisphere each offseason for work, which he continued for eight years.

Allais coached the 1948 Canadian men’s Olympic Team in St. Moritz, Switzerland, before he was recruited again for his services, this time by Otto Lang, executive director at Sun Valley (he also receive an offer around this time from Lake Placid, New York).

“That was quite controversial,” says Dorworth, “because it was 1949 and Emile had been a French Resistance fighter, and Sun Valley was loaded with Austrians and Germans. That was their ski school. So there was a lot of resentment toward Émile.”

Dorworth says at Sun Valley, Allais was assigned to teach beginner skiers on the resort’s mellowest slope—a slap in the face to “one of the best skiers who has ever lived.” While he taught his classes without complaint—Allais was a man of great integrity, Dorworth says—he made a point one day of demonstrating his ability for all to see.

“On his lunch hour he went over to Baldy and went up to the top of Exhibition (an advanced run at Sun Valley) and waited until there were a bunch of Austrians on the chairlift, and then he schussed Exhibition, which had never been done,” says Dorworth, and, from an essay he wrote recounting the same story, “His point had been made on all but the emptiest of heads.”

Allais instructs Dick Buek while coaching the 1952 U.S. Olympic Alpine Team, photo from Allais, la légende d’Emile, courtesy Karen Allais-Pallandre

Three years later, in Allais’ third and final season at Squaw Valley, he was asked to coach the 1952 U.S. men’s Olympic team. In a single winter of training he pulled the team from the bottom ranks of international competition and produced a fifth-place finish by Bill Beck in the downhill and a sixth place by Brooks Dodge in the giant slalom.

Allais went on to coach the French Olympic team for seven years and helped design the French resorts of Méribel, La Plagne, Flaine and Courchevel, where he served as technical director from 1954 to 1964. He was also consulted on the designs of Telluride in Colorado and La Parva in Chile.

Working closely with his longtime sponsor, Rossignol, Allais helped design the Allais 60, a metal ski that Frenchman Jean Vuarnet rode to the gold medal at the 1960 Squaw Valley Olympics, as well as the Strato, which became the world’s first fiberglass ski when it debuted in 1964.

From left, Warren Miller, Pat Bauman, Émile Allais, Jon Reveal, Dick Dorworth and photographer Tom Lippert at Flaine, where Allais worked as director of skiing in 1973, photo courtesy Tom Lippert

A Skier at Heart

Dorworth speaks fondly of meeting his boyhood hero. It was 1973 and he was traveling through Europe filming with Warren Miller and skiers Pat Bauman and Jon Reveal. Flaine was among their stops, where Allais worked as director of skiing and owned a ski shop.

“Émile knew Warren quite well, so he was excited to see his old friend. And because we were with Warren, we were immediately accepted as part of his crew,” says Dorworth, describing Allais as “a gentle, soft spoken, reflective man,” then in his early 60s. “A friend of Warren’s was a friend of his. So he was excited to go skiing with us.”

As Dorworth penned in his essay Europe: Fourth Time Around, the three Americans were in their skiing prime and anticipated having to dial back their speed for the former world champion. After all, Allais was twice their age, with a mane of white hair and “bindings so loose that none of us would be able to make two turns without coming out.” As they quickly learned, their assumption could not be more incorrect.

“None of us will forget that day,” Dorworth noted in his essay. “That evening I wrote in my notebook: ‘Emile really blew us out today… On the first take he just smoked down the mountain doing fast, short turns in marginal snow, jumping off small cliffs and, in short, gettin’ it on. I was grinning (skiing last) and thinking, ‘You sly old fox, Émile.’ And we had to ski to keep up. I loved it.”

Later in the day when they had finished filming, Allais led the group into untracked snow full of trees, gullies and steep, rolling terrain, skiing hard and fast. That’s when Allais gave Dorworth a scare—and a classic story that he still enjoys telling.

“We were cruising along at a moderately high speed when Émile disappeared into a gully, losing it just as he went out of sight,” Dorworth wrote. “I stopped at the edge, more than a little concerned, and looked down to see Émile sitting in the snow, both skis off, snow all over him, and laughing like Chaplin makes you laugh. He laughed and laughed, and I couldn’t help but laugh with him. ‘Oh,’ he said with gentle firmness, ‘it’s good for us to fall down every now and then,’ and he laughed some more.”

“I always remember that,” Dorworth says, “because I was thinking, ‘Oh, shit, the old guy went down. I hope he’s OK.’ And he’s sitting there laughing. He was great. That was just a beautiful day of skiing. It’s always thrilling to ski with one of your heroes.”

Émile Allais with his grandchildren, Lou and Émile, photo courtesy Karen Allais-Pallandre

Skiing Family

By the time Dorworth met Allais in 1973, he had remarried (Georgette died in 1970) and had a 3-year-old daughter, Karen, who went on to ski for the French national team along with her younger sister, Kathleen. Karen was set to compete in the 1992 Albertville Olympics but was injured shortly before the Games, while Kathleen skied in the 2002 Salt Lake City Olympics.

Allais raised his daughters in his hometown of Megéve, where Karen raised her own family and Allais lived out his final years until his death in 2012 at the age of 100.

As others who knew Allais express, Karen says her father was known as much for his character as he was for his skiing exploits. In fact, it wasn’t until she was older that she understood what an impact he had on the skiing world.

“I never realized that much that he was so known and important, but I got to realize that once I started traveling to different places like the United States and Chile, for example, and people would pass and say, ‘Wow, you are Émile Allais’ daughter. That is incredible.’ Some people would start to cry when they saw me,” says Karen. “People who knew him would always say, ‘Your father was so nice,’ and they always spoke about the way he treated people.”

Lou Pallandre, the granddaughter of Émile Allais, races for Colfax High School last winter, photo by Harry Lefrak

Karen’s two children grew up ski racing as well. Her daughter, Lou, came to the United States last year as a high school foreign exchange student. As fate would have it, she was placed with a ski-racing family who lives in Colfax and skis weekly at Squaw Valley in the winter. Ironically, Lou chose California to get away from skiing and the mountains, envisioning balmy weather and palm trees.

“I live in the mountains in France, so I wanted to be near the beach. That was kind of the point of coming to California,” she says. “And then I learned that I was going to live with a family that loved skiing and had a house at Squaw, and so I was sad at first. I was like, ‘No! Why?’ But then I came and met the family, and my host sister became my sister, and now I can basically say that I have a second family and a second home here in California.”

A former junior national champion in alpine racing, Lou injured her knee before returning to the sport and then eventually walking away when she was not selected for France’s national team, says her host father, Bryan Martel.

“She had national pressure and parental pressure, and she just did not want to go back to that sport,” says Martel. “That’s why she came here. She was escaping.”

Nevertheless, Martel and his daughter, Karina, convinced Lou to race for the Colfax High School team, which Martel coaches. The team ended up winning the state championship, beating out all the powerhouse Tahoe schools.

Lou Pallandre, right, with her host sister, Karina Martel, at Squaw Valley in spring 2019, nearly 70 years after Pallandre’s grandfather established a tradition as the resort’s first ski school director, photo by Harry Lefrak

As a ski instructor himself at Squaw, Martel never missed an opportunity to tell people about Lou’s famous grandfather. But his praise fell mostly on uninterested ears.

“He’d be in the lift line and tell people, ‘She’s from France and her grandfather was the first ski instructor here,’” says Lou, who cherishes memories of skiing with her grandfather as a child. “But most people didn’t really care or know who he was.”

As Dorworth says, it’s a shame that the man who set the precedent at Squaw Valley from year one does not receive more credit today. But those who know Tahoe’s skiing history know that it was Émile Allais, the great French champion, who started Squaw Valley’s longstanding tradition of excellence.

“Basically, Émile was the beginning. He was the number one guy, and he passed everything on,” says Tom Kelly. “Squaw Valley has such a great tradition of racing, and it all started with Émile.”

Tahoe Quarterly editor Sylas Wright admits that he, too, was not aware of Émile Allais’ impact on Squaw Valley and the greater skiing community until researching this article. He knows now.

Bryan Martel

Posted at 15:29h, 03 FebruaryHi Sylas, we learned lot about our Tahoe skiing traditions from having Lou live with us for a year. This summer we traveled to Chamonix and met Lou’s family and learned even more from their French perspective. Your article did justice to a great man who had a tremendous influence on our region and the greater community of all skiers. Thanks for the great article. Bryan