25 Jun Ty Cobb: A Tamer Tiger at Tahoe

Known for his fiery and impulsive personality, the baseball great was not as crude as his reputation suggests

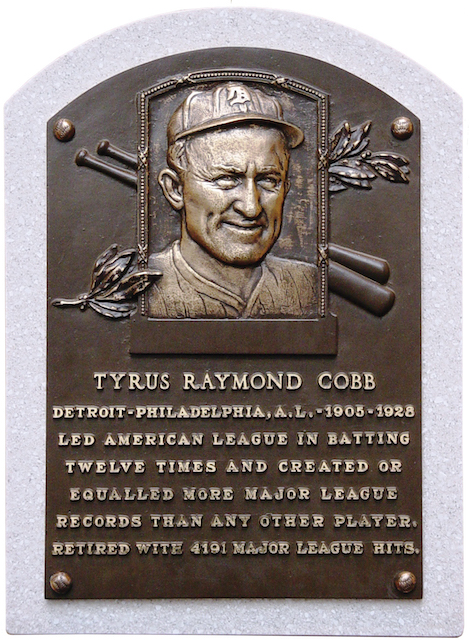

Cobb’s plaque in the Baseball Hall of Fame, courtesy photo

Apocryphal (adj): of doubtful authenticity, although widely circulated as being true.

There are two versions of Ty Cobb at Lake Tahoe.

Two stories representing each are set against wild weather events at his East Shore cabin near Cave Rock. They paint a picture of baseball’s first Hall of Famer as a man guided by impulse.

The Heatwave

One is told by his grandson, Herschel Cobb, an attorney and author based in Menlo Park, California.

Herschel Cobb’s story—which he told to Tahoe Quarterly but also appeared in his 2013 book, Heart of a Tiger: Growing Up with My Grandfather, Ty Cobb—takes place during a blisteringly hot summer afternoon at his grandfather’s 2,000-square-foot lakeside Zephyr Cove cabin in the mid-1950s.

A four-day heatwave sent temperatures into the mid-90s, and an inversion layer made the pressure unbearable.

Herschel, along with his older sister Susan and younger brother Kit, were spending time with “Granddaddy” at his cabin. It was a summer ritual for the trio, an escape from a home life that was both abusive and neglectful.

The kids—Herschel was then in his early teens—beat the heat by trotting down to the lake for a dip in its cool waters. Cobb, about 70 years old at that point, suffered from diabetes and a host of other age-related ailments. He struggled to leave the house in the extreme heat and was trying to seek comfort in a midday nap in his bedroom, which had a lake view.

“If there was anything Ty Cobb didn’t like, it was weather that reminded him of a hot summer day in Georgia,” Herschel Cobb says. Ty Cobb—nicknamed the Georgia Peach for his home state—grew up in rural Royston, Georgia, which is known for its humid, subtropical climate.

“He was very uncomfortable and totally without energy,” Herschel says of his grandfather on that hot Tahoe day. “He just wanted to sit in his chair and try to sleep. On the fourth day, it was dramatic. He was in his room, trying to take a nap, when all of a sudden he bolted out of bed and started shouting: ‘Susan, Herschel, quick! Grab all the sheets off the beds!’”

The interior of the lakefront home once owned by Ty Cobb on the East Shore of Lake Tahoe. The home is currently for sale, listed at $4,995,000 by Craig Zager with Coldwell Banker, photo courtesy Coldwell Banker

Cobb—dressed in a short-sleeve button-down shirt and pants that were rolled up to relieve the heat—sprinted into a spare bathroom and turned on the shower. He was soaking bedsheets under the cold water and frantically calling for the kids to strip the beds and bring more sheets to him.

“He was soaking wet—and Susan and I looked at each other like it had finally happened. He’d went nuts,” Herschel says.

But the dutiful grandchildren stripped all the beds, grabbed extra sheets from the linen closets, and handed them to their sopping Granddaddy.

Cobb instructed Herschel to fetch a ladder, hammer, nails and thumbtacks from a workroom. Then the old Detroit Tigers star nailed and tacked the sheets over the windows on the lake-facing side of the cabin.

“He stepped back and I could see a slight breeze billowing the sheets,” Herschel says, recalling that the cold water soaked into the sheets cooled the breeze, and the inside of the cabin. The Cobbs affixed sheets to the rest of the doors and windows and luxuriated in this bit of backcountry air-conditioning.

“We just sat there and finally relaxed,” Herschel says. “During the course of the evening the wind picked up and the heat finally broke. I remember Granddaddy saying, ‘You didn’t know your grandfather had such tricks, did you?’”

Ty Cobb signs autographs at an old-timers game, photo courtesy Ty Cobb Museum

The Blizzard

The other Ty Cobb story—written by Al Stump in a 1961 True magazine article—takes place during a blizzard in the winter of 1960. It’s widely regarded as fictionalized. Stump was working with Cobb to “set down the true record” of his 24-year baseball career in a sanctioned autobiography.

In Stump’s telling, the Los Angeles–based writer and the 73-year-old were planning a 1 a.m. trip to Reno at Cobb’s insistence. Stump’s Cobb is heavily medicated, drunk and intent on driving himself to a craps table in the Biggest Little City.

They set off in separate cars down Highway 50 to reach Reno via Carson City, with Cobb originally following Stump:

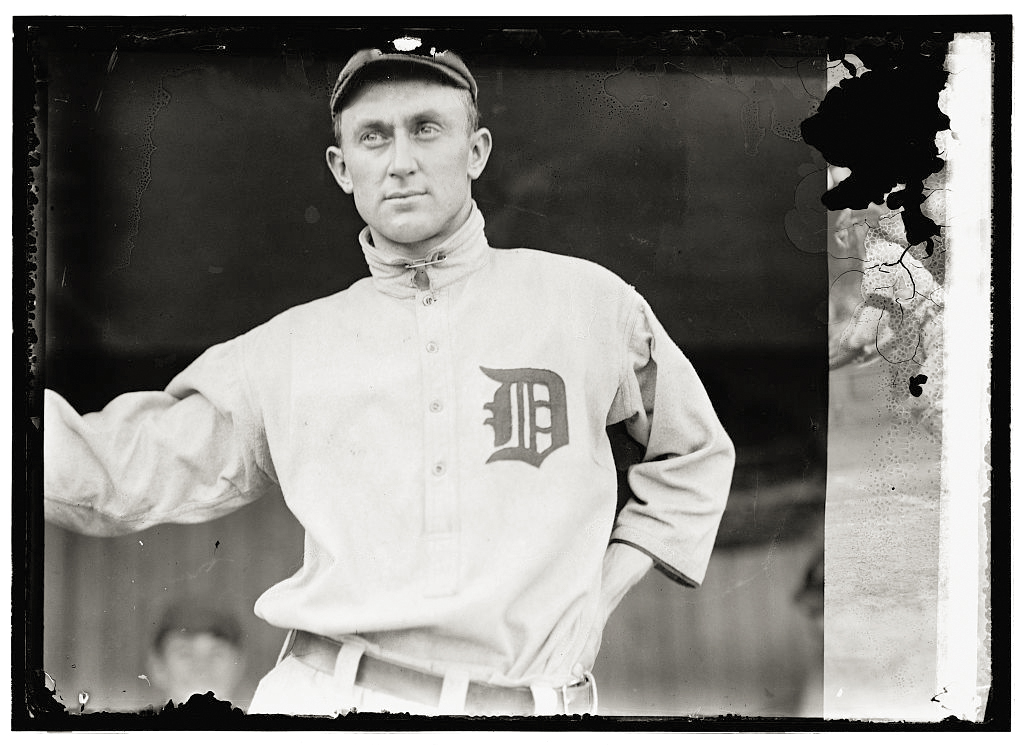

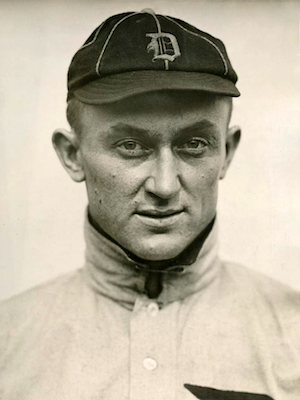

Cobb in 1913, courtesy photo

“And then here came Cobb. Tiring of my creeping pace, he gunned the Imperial around me in one big skid. I caught a glimpse of an angry face under a big Stetson hat and a waving fist. He was doing a good 30 m.p.h. when he had gained 25 yards on me, fishtailing right and left, but straightening as he slid out of sight in the thick sleet.

“I let him go. Suicide wasn’t in my contract.

“The next six miles was a matter of feeling my way and praying. Near a curve, I saw tail lights to the left. Pulling up, I found Ty swung sideways and buried, nosedown, in a snowbank, his hind wheels two feet in the air. Twenty yards away was a sheer drop-off into a canyon.”

Cobb exits the vehicle and insists on continuing the trip, which ends with Cobb gambling in Reno—and attempting to punch a casino employee, then smashing a wooden rake over a craps table—with an exhausted Stump in tow.

Historians, and the people who knew him, have discredited Stump’s Cobb—who, while at times a drinker and certainly impulsive, probably never took that trip down the mountain. He also almost certainly wasn’t a racist, which is the charge Stump stuck him with most damningly in the public imagination.

Sales of Cobb’s autobiography, titled My Life in Baseball: A True Record, never met Stump’s expectations when it was released in 1961, the year Cobb died in Atlanta’s Emory University Hospital.

So, Stump created his Cobb, the violent, drunken racist, first in the True piece and then in two successive books.

In 1994, Warner Bros. adapted Stump’s work into a screenplay starring Tommy Lee Jones titled Cobb. Stump’s charges of racism also made their way into Ken Burns’ Baseball documentary, released that same year, and the die was cast.

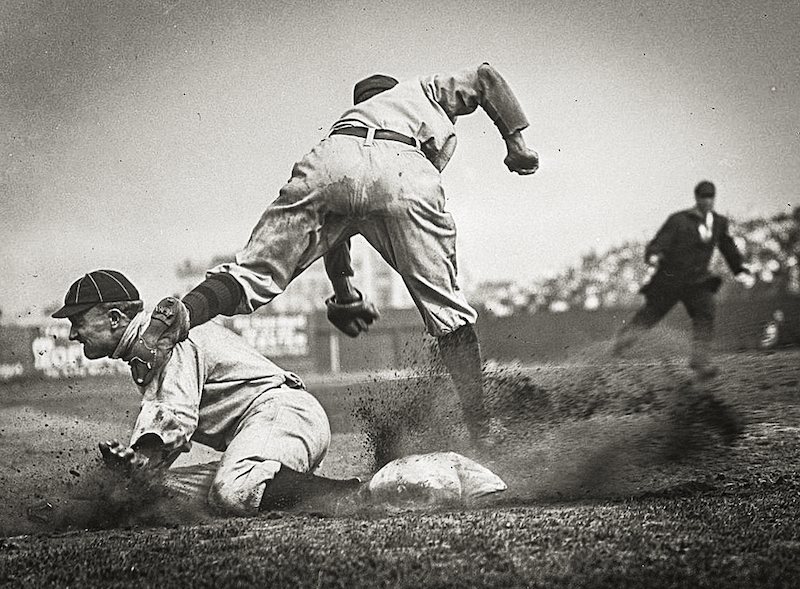

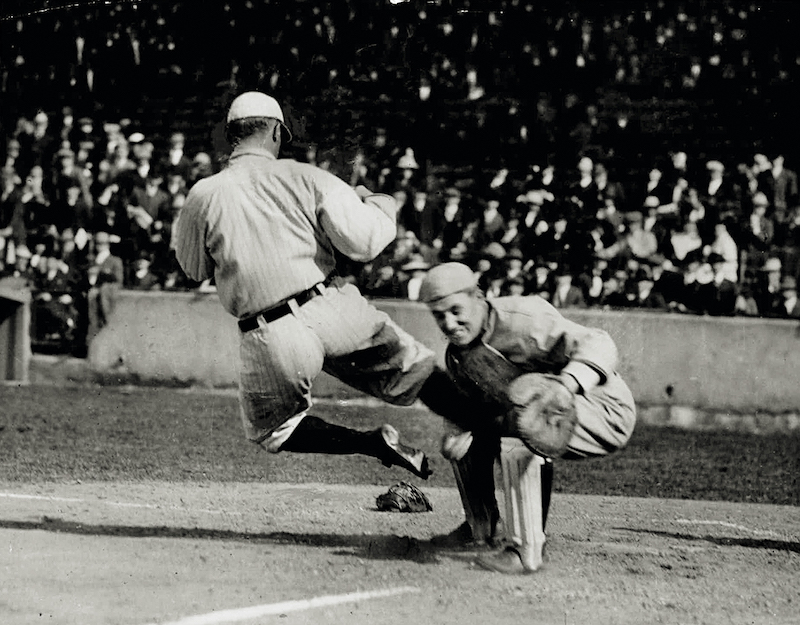

Charles M. Conlon’s famous photo of Cobb stealing third base during the 1909 season, courtesy photo

The Truth

In point of fact, no newspaper or writer during Cobb’s life recorded him making a racist statement.

Author Charlie Leerhsen’s 2015 biography on Cobb, Ty Cobb: A Terrible Beauty, digs extensively into the record and comes up empty, beyond Stump’s reporting and its parrots.

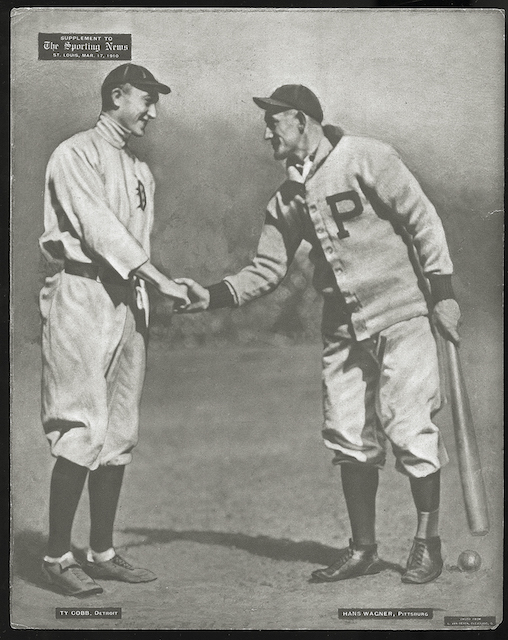

Ty Cobb, left, shakes hands with Honus Wagner in 1909, courtesy photo

In a May 2020 story for the Detroit Free Press, a reporter for the paper found that a retired Cobb took a train in 1930 from Georgia to Detroit—then a Ku Klux Klan hotbed—to help open Hamtramck Stadium, the new digs for the city’s Negro League franchise, the Detroit Stars.

“That is not something someone would do if they were truly racist,” Leerhsen told the paper.

Cobb was also on record praising baseball’s racial integration in 1947 and calling Willie Mays—the San Francisco Giants’ centerfielder and the only man at that position whom baseball historians put ahead of Cobb in achievements—as being the only ballplayer he’d pay money to see.

Stump didn’t invent Cobb’s reputation for drinking, antics and violence from whole cloth, though.

Around Tahoe, Cobb was known for his “hard-drinking, hard-partying” friendship with George Whittell Jr., owner of the East Shore’s iconic Thunderbird Lodge, says Bill Watson, its chief executive and curator. All-night poker games between Cobb, Whittell and Howard Hughes are a key part of Thunderbird Lore.

Another biographer, Charles Alexander, included a story in his book Ty Cobb about Cobb beating a grocer in Detroit in 1914.

As the story goes, the man offended Cobb’s wife, Charlie (Charlotte), and Cobb took a pistol to his shop to demand an apology. The grocer’s brother-in-law, an employee at the market, pulled out a butcher’s knife and demanded he leave. Cobb challenged the man to a fight on the sidewalk in front of the store, and beat him soundly, breaking his thumb on the man’s skull. Both men were arrested for fighting, according to the Free Press.

Alexander reported the man’s race as black, which may have contributed to Cobb’s reputation as a bigot. Leerhsen, in his research, found the man listed as white in a census form.

Another incident, in 1909, found Cobb visiting Cleveland’s Euclid Hotel during a road series. After a night out, Cobb tried to get a teenaged bellhop to take him to the hotel’s second floor, where he heard a poker game was going on.

Because it was about 2 a.m., or perhaps because Cobb was drunk, the bellhop told him he could only take him to his own floor, the third. Cobb, in turn, beat him up. In Alexander’s and Stump’s telling, the bellhop was black. But, Leerhsen finds no evidence of the bellhop’s race in contemporaneous accounts.

Ty Cobb slides spikes high into a catcher blocking the plate, courtesy photo

The Gambler

Cobb also embraced risk. One doesn’t steal 897 career bases in an era when infielders sharpened the spikes on their shoes and stomped on opponents’ feet and legs without taking a few chances.

In fact, Herschel figures, being a bit of a gambler is how Cobb ended up with his Lake Tahoe home. Purchased during the dark days of the Great Depression in 1933—five years after Cobb retired from baseball—Herschel calls the investment “chancey,” but points out that it fits a larger pattern of behavior for his grandfather.

Cobb, an avid sportsman, removes a brier from the paw of one of his favorite dogs, photo by © Bettmann/CORBIS, courtesy Ty Cobb Museum

Cobb built his wealth—estimated to be around $110 million in today’s dollars at the time of his death—on risks, rather than just baseball.

He was the game’s pre-eminent star during his 24-year career, amassing a lifetime .366 (or .367) batting average (baseball historians disagree on the figure) on 4,189 career hits, which stands as the highest career average of all time. A rarity in today’s major leagues, Cobb recorded more than 200 hits in a season on nine occasions, including his 1911 MVP campaign when he posted a .419 batting average with 248 hits, 127 RBIs and 83 stolen bases.

Yet, he battled every year with Detroit Tigers owner Frank Navin, a notorious penny-pincher, over his salary, Herschel says.

“He was determined to be monetarily independent of baseball,” says Herschel, whose grandfather earned roughly $491,000 total (not counting possible bonuses) during his career, according to Baseball-Reference.com.

Cobb looked around 1910s Detroit and clearly saw what direction the nation was going, and that they’d get there in a car, so he invested early in General Motors and Chrysler.

He also made money by endorsing Coca-Cola, then a regional soft drink interest in Georgia. When Robert Woodruff bought the company in 1919, he counseled Cobb to invest, telling him it was going to become one of the country’s most successful companies. Cobb didn’t have the money to buy stock, so he borrowed $400 from Woodruff to purchase it.

The rest is history. Cobb profited handsomely from the arrangement and went on to own Coke distributorships up and down the West Coast. In Heart of a Tiger, Herschel remembers finding an uncashed $83,000 dividend check when cleaning his grandfather’s dining room table in the 1950s.

The lakefront home once owned by Ty Cobb on the East Shore of Lake Tahoe. The home is currently for sale, listed at $4,995,000 by Craig Zager with Coldwell Banker, photos courtesy Coldwell Banker

Finding Family Again

Leslie McLaren, Ty Cobb’s granddaughter, remembers a different story involving him and Coca-Cola. The two lived next door to each other when McLaren was a child in Atherton, California.

“He’d look for me after school each day,” McLaren says. “He’d invite me in for cake and Cokes if he saw me. What a diabetic was doing eating cake and drinking Coke, I’ll never know. But that was grandfather. He was very warm.”

Ty Cobb and family in Paris, France, circa 1929, photo by © Bettmann/CORBIS, courtesy Ty Cobb Museum

McLaren went on to own the Cobb cabin with siblings after her mother and aunt Shirley purchased it from her grandfather’s estate after his death. The family sold the property in 2016.

Both McLaren and Herschel recall tender relationships with their grandfather, but friction between him and their parents—Herschel’s father, Herschel Sr., and McLaren’s mother, Beverly.

Cobb had long lived a fraught family life.

During his rookie season in 1905, Cobb’s mother shot and killed his father, mistaking him for a burglar. She was charged and later acquitted for his murder.

Cobb struggled in relationships with his children, barely speaking with his son Ty Jr. for the 30 years before his death in 1952.

“My theory is that he regretted the way he treated his own children. He always expected them to be the very best and didn’t know why they couldn’t be,” McLaren says.

After losing Herschel Sr. and Ty Jr. in back-to-back years, Cobb embraced his grandchildren.

“Ty Cobb regained his family through his grandchildren,” Herschel says.

He forged those connections largely at Lake Tahoe. His cabin was a refuge—a place where he slept well and connected with the natural world.

Both Herschel and Leslie fondly recall traipsing through the woods south of Cave Rock to a small spring where they filled a small cistern with water to have around the cabin. Trips around Tahoe with Cobb were great fun. A highlight was taking his 26-foot Chris-Craft boat to Glenbrook to get the mail and chat with locals. And Cobb—a dedicated fisherman—was known to string a line from his home down more than a hundred feet to the water to wait for a bite.

“Grandfather came home to himself in Tahoe,” McLaren says. “He was not a well man by the time I really remember him (McLaren was 12 when he died), but he could be at peace up there.”

Kyle Magin is an Austin, Texas-based writer and editor and a lifelong fan of the Detroit Tigers.

David Armstrong

Posted at 08:21h, 26 JuneGreat story – thank you!

Jim Ingram

Posted at 15:41h, 11 AugustI was an 18 year old college boy from San Rafael CA. on summer break looking for a job at Lake Tahoe. No luck looking at So.

shore or Zepher Cove so I went up the road just past Cave Rock were I found the Sky Water Lodge. They needed a flunky type house boy to do needful chores. I found out that Ty Cobb lived next door but wouldn’t dare approach such a famous supper star and ask for an autograph. One day while raking pine needles in the driveway who should I see but the great Ty Cobb returning from his mail box with an arm full of mail. “Good morning Mr. Cobb” I blurted out. “Good morning…come on over!” I drop my rake right there and hoped over low rock wall. He graciously escorted me into his house and sat me down at his kitchen table and started sorting thru his mail. Being in such a state of star stuck shock I don’t remember what we talked about. Through the following 65 years I’ve told the story many times, people always ask “did you get his autograph?” ” No, I forgot!”

Tahoe Quarterly

Posted at 22:56h, 11 AugustThat is a great story, Jim! Thanks for sharing.

National TY COBB Historian

Posted at 07:01h, 26 SeptemberTy Cobb batted .367 over 24 big league seasons from 1905-1928. His career batting average of .367 and his career hits of 4,191 are the official stats recognized by Major League Baseball, Ty Cobb, and Elias Sports Bureau, the official statistician of Major League Baseball since 1913.

The incorrect batting average of .366 was brought before the MLB records committee on Saturday April 13, 1981 and because of inconclusive evidence, the inability to change all player errors and the expiration of the statue of limitation, Major League Baseball declined to change Ty Cobb’s batting average and his career hits total of 4,191.

Therefore, his career batting average of .367 will continue to be the ideal mark for young baseball players to aspire to duplicate.

Discover More At The Atheneum: https://www.tycobb.org/ty-cobb-stats