25 Jun Winged Wonders

The Tahoe region has long been a hotspot for the study of native and migratory butterflies

California tortoiseshells were seen in large numbers in Tahoe late last summer, courtesy photo

Anyone who was in the Tahoe region in August 2019 saw butterflies—lots of them. Insects are good at capitalizing on favorable weather and food availability, and last year, conditions were perfect for California tortoiseshells.

Swarms of these attractive butterflies erupted throughout the region in unprecedented numbers, and the spectacle had everybody talking. As social media became awash in streams of fluttering orange masses, the Tahoe Institute for Natural Science received daily interview requests from news outlets and phone calls from out-of-towners wanting to drive up to witness the show.

The butterflies were certainly a lot of fun, but I was likewise thrilled that so many people were paying attention to insects. For a brief moment, butterflies captured the imagination of seemingly everybody at Tahoe.

In a general sense, butterflies have always been a part of our consciousness. Their buoyant flight and bold colors have delighted human eyes since the dawn of history. Aristotle gave butterflies the name “psyche,” the Greek word for soul, and in many cultures they remain potent symbols of metamorphosis, freedom or simply joy.

But for many, these animals comprise the ideal subject for closer examination. Few readers may realize that the Tahoe region, with Truckee and Donner Summit in particular, has been a center of butterfly study for nearly 150 years.

The western tiger swallowtail is one of Tahoe’s largest butterfly species, photo by First Tracks Productions

Truckee’s Original Collectors

It all started in 1871 with Charles Fayette McGlashan, then a fifth-grade school teacher, taking his students on a field trip to an amateur scientist’s home near Placerville. There, they witnessed a sizable collection of moths and butterflies proceeding through their developmental stages in cloth-covered cages.

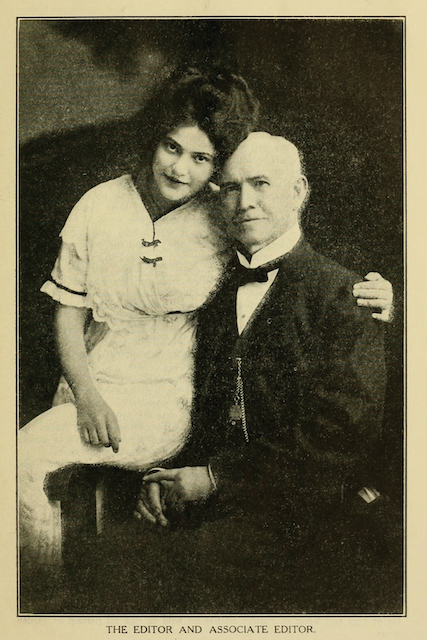

Charles McGlashan and daughter Ximena, who was also known as Truckee’s “butterfly princess,” courtesy photo

McGlashan returned to the scientist’s home to learn all he could about the study of lepidoptera (butterflies and moths), but within months he was relocating to Truckee to become the new school principal.

For the next several decades, McGlashan dedicated himself to the pursuit and study of butterflies and moths, all while keeping busy as a defense attorney, owner and editor of the Truckee Republican, historian of the Donner Party, promoter of winter sports and politician. He had a voracious curiosity and wide interests. Unfortunately, once the transcontinental railroad was completed, he used his role as newspaper editor to spearhead an anti-Chinese boycott in Truckee and beyond.

Nevertheless, butterflies remained among his greatest passions. He once confided, “Give me a mountain meadow, and you can have the metropolises of the world. I would rather chase butterflies on the Truckee meadows than compete for position and fees and fame in any city.”

Of his eight children, only his daughter Ximena took an interest in butterflies. Ximena’s specialty was lepidopteran husbandry, and as a teenager she developed and perfected techniques of rearing the animals in jars, boxes and barrels, allowing for pristine specimens that could fetch high prices. Butterfly collecting was wildly popular in Victorian and Edwardian times, reaching its peak in the early 1900s and making the timing perfect for the country’s first commercial butterfly farming venture.

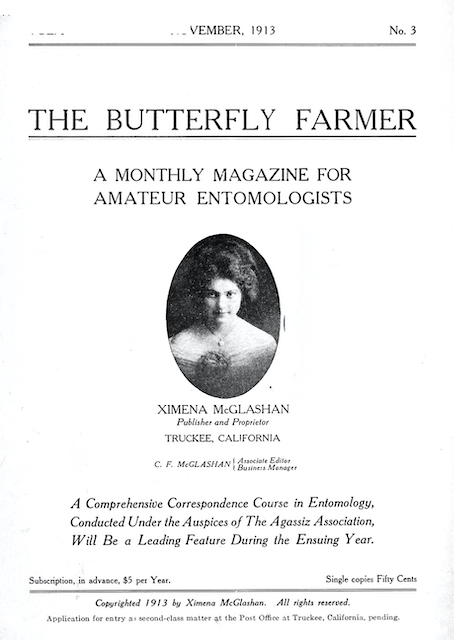

With Ximena’s mastery of the craft and her father’s experience in publishing, the two launched a magazine called The Butterfly Farmer (1911–1914). The publication included tips for butterfly farming, with everything from collecting eggs in paper bags and methods for specimen preparation to contracts and shipments. Content also included lists of dealers and buyers, submissions by famous entomologists on beetles and other insect orders, and a basic correspondence course in entomology.

In the magazine’s final year, Ximena published species lists of Truckee butterflies and moths that, combined with Erval Jackson Newcomer’s 1910 publication on butterflies of the Lake Tahoe Basin, gives modern scientists a valuable baseline inventory of the region’s fauna from 100 years ago.

A Lucrative Trade

The cover of Ximena McGlashan’s magazine, The Butterfly Farmer, courtesy photo

While The Butterfly Farmer was a successful venture, the real money was in the trade of specimens. In her first two weeks of effort, Ximena shipped 1,500 specimens and received a check for $75 in the mail (over $2,000 in today’s dollars). By 1914 she was averaging $50 a week, sometimes more, selling specimens for 5 to 12.5 cents each with $25 minimum orders. With her earnings, she enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley, for a year before transferring to Stanford University, where she graduated with an entomology degree.

The McGlashans provided another valuable service: With the railroad passing through Truckee, the town became a convenient stopover for visiting lepidopterists, most of whom were amateur entomologists of considerable financial means. Charles and Ximena could meet collectors at the train station and ride off on horseback on guided expeditions into the mountains and meadows surrounding Truckee.

This quickly put Truckee on the lepidopterist map. Visitors included prominent names like Berthold Neumogen, a New York banker and stockbroker fluent in six languages; Captain J. Gamble Geddes, a banker, political appointee and authority on Canadian butterflies; Henry Edwards, a British-born stage actor and prolific entomologist who named new species after female characters from Shakespeare plays; and Herman Strecker from Pennsylvania, who owned the largest private butterfly collection in the Western Hemisphere before it was purchased by the Field Museum in Chicago.

Between Ximena’s brisk trade and the steady stream of visiting collectors, thousands of Truckee butterflies ended up in the most important collections in the world. At its peak, the McGlashans’ collection was quite substantial as well, reaching an estimated 20,000 butterflies and moths from around the globe.

As entomology advanced, butterfly study became less about collecting and more about understanding the animals themselves or examining them as models to unlock broader ecological principles. In the early 1960s, John and Thomas Emmel settled on the Donner Pass area for several seasons of intensive study. Their work was foundational to scientists’ understanding of basic distributional patterns of butterflies: Weather and climate dictate when they fly, and vegetation communities and landscape dictate where.

Milbert’s tortoiseshells often move upslope in summer and back down the mountains in fall, photo by Will Richardson

Butterfly Hotbed

The Tahoe-Truckee region hosts a remarkably rich aggregation of butterflies. The relatively low passes in the area allow Great Basin and Pacific Slope species to intermingle. The higher elevations, bogs and fens can hold boreal relicts, and the complex topography of mountain areas lends itself to isolation and speciation.

This speciation is ongoing. The Emmel brothers discovered and described a new species, the Heather blue from Desolation Wilderness, in 1998. A stable hybrid species of blue butterfly in the genus Lycaeides was discovered at high elevations around Lake Tahoe in 2006 but has yet to be formally named.

Lembert’s hairstreak can be found in windswept sage from Martis Valley to the highest ridges in the Tahoe region, photo by Will Richardson

To understand why certain species occur where they do, it is important to know that butterflies gain most of their energy during the caterpillar stage, by eating the leaves of plants. Because plants would rather not be eaten by hungry caterpillars, they produce chemical defenses that make them unpalatable, but some butterflies evolve a tolerance to these defenses, often becoming dependent on that very plant as the only type it can eat. This whole process can drive speciation of both butterflies and plants, but it also means that butterflies are only found where their larval host plants are found.

As plants have specific climate and soil requirements, so do the butterflies, directly or indirectly. For example, showy milkweed has only been found growing within the Lake Tahoe Basin since about 2012. Historically, monarch butterflies only passed by Tahoe on migration, but as the milkweed has expanded its range into the Tahoe Basin, monarchs have started reproducing and laying eggs at Tahoe.

Butterflies that are tied to small ranges generally do not disperse well and make poor colonizers of new habitats. Many of Tahoe’s species, however, are characterized by their strong flight.

Larger species like swallowtails can often be seen patrolling a territory, back and forth, all day long. Our Speyeria fritillaries never seem to land and never appear to have any particular direction of travel. Many species are quite purposeful in their flight and follow predictable patterns.

Tahoe is a terrific place to witness hill-topping, which is a strategy many insects employ to seek out mates by flying to ridgetops and summits. After mating, the females descend to find host plants, and the males generally descend to get out of the wind and seek nectar, minerals from mud and other resources.

The strongest fliers of all are the seasonal migrants. Unlike vertebrate migration, where single animals complete a full migratory circuit, insect migration usually requires several generations to make a full lap. Butterfly migration at Tahoe can be elevational, as is the case with California and Milbert’s tortoiseshells; an expansion from wintering territory in warmer parts of the American Southwest, which is seen with painted ladies streaming north in March and April and buckeyes headed south in fall; or an expansion from wintering territory along the Central Coast of California, which we see with western monarchs.

Butterflies temporarily placed in jars allow for close study at the annual South Lake Tahoe Butterfly Count, photo by Will Richardson

Counting Butterflies

To help monitor all this diversity, the Tahoe Institute for Natural Science coordinates a butterfly count in South Lake Tahoe each July. The count is open to all participants, who regularly travel from the Bay Area and elsewhere in California and Nevada to spend a day with Tahoe’s unique and impressive suite of species.

An anise swallowtail caterpillar pictured during the annual Sagehen Bioblitz, photo by Will Richardson

In the 10 years of conducting the count, most of those years were consumed by drought, so we haven’t seen many trends that can’t be attributable to shorter-term precipitation patterns. However, we have also documented first records for a couple of species more commonly associated with southwestern deserts—the marine blue and western pygmy blue, two species that appear to be expanding their ranges both northward and uphill.

Art Shapiro, a lepidopterist at University of California, Davis, has been monitoring the butterfly diversity and population trends along a transect that spans the elevational gradient from the Bay Area to Tahoe, with 10 sites along the Interstate-80 corridor, and one each at Donner Pass and Castle Peak. Starting in 1972, he has conducted bi-weekly transect counts through the butterfly flight season every year. It is the longest continually running butterfly monitoring project in the world, and it involves knowing a long list of often frustratingly similar-looking butterflies by sight.

One day in June in the early 1990s, Shapiro observed 62 species along a 4-mile stretch of Old Highway 40. For perspective, consider that only 71 species have been recorded in the entire British Isles, and only 59 occur there today. With this incredible dataset, Shapiro and collaborators like Matt Forister, a former student who is now a professor at the University of Nevada, Reno, have been teasing out long-term trends and changes as well as finding signatures of climate change.

In recent years, Forister and his lab have taken over responsibility for sampling the Donner Summit and Castle Peak sites. Graduate student Chris Halsch conducts survey transects at these sites every other week from late spring through early fall. Halsch tells me that when he first started this project, he didn’t quite realize the sense of responsibility he’d feel for this dataset.

“At the beginning I suffered impostor syndrome pretty bad,” he says, adding that he’s thankful to have Shapiro to send photos and specimens to for confirmation. This ensures that the data quality of the project remains consistent, as it has for nearly 50 years.

A Clodius parnassian pauses for participants before being released at the annual Butterfly Count coordinated by the Tahoe Institute for Natural Science, photo by Will Richardson

A Collection Preserved

And what became of the McGlashan’s personal butterfly collection? McGlashan created an artistic presentation for approximately 1,200 of his favorites: four large wooden panels comprising 15 sections each, hinged together and displaying colorful geometric arrangements of the insects (with no regard to taxonomy or geography).

This display took 41 years to complete and was a highlight of McGlashan’s own Rocking Stone Tower museum for years, before moving to the Nevada County Courthouse in Nevada City from 1935 to 1996. The Emigrant Trail Museum at Donner Memorial State Park housed the panels up until 2015, when, thanks to efforts by the McGlashan family and the Truckee-Donner Historical Society, they were installed at the Truckee Community Recreation Center—appropriately enough, right next to the Butterfly Preschool.

As the specimens lack labels, they are, unfortunately, of little scientific value. But they are lovely to behold, and I am hopeful that they will inspire future generations to continue the legacy of butterfly study in the Tahoe-Truckee region.

Biologist Will Richardson is the executive director of the Tahoe Institute for Natural Science, www.tinsweb.org.

Claudette

Posted at 13:57h, 31 JulyWhile backpacking to Lake Paradise in I think August many years ago we had the great experience of hiking with a butterfly migration going on all around us. It was magical especially since we hadn’t planned on being there for it. While hiking in we did meet some people who had specifically planned to be there for the migration.The butterflys looked like a smaller version of a monarch. It was magical!

Will

Posted at 13:23h, 22 SeptemberThose would’ve been California Tortoiseshells