25 Jun A Decade of Devotion

Since its inception amid a contentious era in the Tahoe Basin, the Tahoe Fund has served as a unifying force in its ongoing effort to restore and preserve a national treasure

Construction on the Lily Lake Trail, one of many projects made possible by the Tahoe Fund and its partners, photo courtesy TAMBA

As the world emerges into new phases of living with the COVID-19 pandemic, people are going to need places like Tahoe. Alongside the orders to stay at home, the World Health Organization recommends that people get outside. Marty Makary, a professor of health policy at Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, told the New York Times in May: “The outdoors is not only good for your mental state. It’s also a safer place than indoors.”

Outdoor places like Lake Tahoe inspire a sense of awe. Researchers at UC Berkeley pinpointed awe as the specific emotion—more so than joy, amusement or a sense of contentment—that helped veterans with post traumatic stress disorder feel the biggest boost to their sense of wellbeing. Those of us who know Tahoe can understand that feeling. After the first wave of coronavirus, people felt a deep craving for the sense we get when we crest the summit of Mount Tallac, dive off a pier into Tahoe’s frigid water, or walk in a world of sky and water along the Tahoe East Shore Trail.

The question is, will Tahoe be ready when millions of visitors arrive in the midst of a pandemic?

In the middle of May, Amy Berry, CEO of the Tahoe Fund, was looking for solutions. She had recently been on a call with several dozen recreation site managers who, according to Berry, were experiencing a surge in visitation unlike anything they had seen before. Because of COVID-19, land managers shut down access to public lands across California and Nevada, including the Tahoe Basin—gates were closed, as were bathrooms, parking lots, picnic areas and campgrounds. It was still early in the spring, so land managers hadn’t even fully staffed up for peak season, and yet, the onslaught of tourism had already started.

“Our land managers are completely overwhelmed by the huge influx of people visiting Tahoe,” Berry says. “We’re in meetings with them all day every day trying to understand from them, how can we help?”

Donors’ names appear on plaques shaped like trout along the Tahoe East Shore Trail, photo courtesy Tahoe Fund

For the last 10 years, the Tahoe Fund, a nonprofit that funnels philanthropy and donations to projects that restore the environment at Lake Tahoe, has been a major resource to the Tahoe Basin. The Tahoe Fund champions private-public collaboration. And it has been very successful in this model. In the last five years, it has leveraged $2 million of private funding into more than $40 million of public funding. The Tahoe Fund takes its partnerships one step further. It not only provides the money, it convenes people—from U.S. senators and state governors to local volunteers. As a result, the organization has collaborated on dozens of projects to restore Tahoe’s forest health and lake clarity, build trails, donate mountain bikes to kids, battle aquatic invasive species, restore pivotal components of the Tahoe watershed, educate tourists about stewardship and much more.

Now, after COVID-19, Berry says the Tahoe Fund is applying another filter to its work: How can environmental restoration projects also put people back to work?

This summer, Berry says the organization is eager to support projects like trail restoration that give a crew of people full-time work for up to 10 weeks and are an investment in both the environment and the economy.

“That’s really important,” Berry says. “Yes, things are crazy. But the Tahoe Fund is here for the long haul. We’re going to continue to do the work that we set out to do.”

With help from Nevada Governor Steve Sisolak, Tahoe Fund members and supporters cut the ribbon during the opening celebration of the Tahoe East Shore Trail, photo courtesy Tahoe Fund

Rising from Strife

Ten years ago, the Tahoe Fund was born into another moment of crisis in Lake Tahoe.

A boom of investment in the late 1990s and early 2000s to restore Lake Tahoe’s clarity had made some progress, but there was still a lot of work to be done. Then, the Great Recession hit, and public funding for restoration work in the Tahoe Basin dried up. Local businesses were hurt and trying to recover. Land managers needed financial help to get bike paths built and state parks opened. Meanwhile, the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency was in the throes of its Regional Plan Update, a fraught document that is thousands of pages long and attempts to outline all aspects of environmental regulation, development, transportation and more. In 2011, Nevada threatened to pull out of the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency unless California and the federal government could compromise. Meanwhile, development was proposed to reconstruct places like Homewood and Kings Beach, and beyond the Basin in Squaw Valley and Truckee. Environmental groups fought back with lawsuits.

Cindy Gustafson, founding chair of the Tahoe Fund, with former Nevada Governor Brian Sandoval, photo courtesy Tahoe Fund

“Those days were very divisive in the Tahoe Basin,” says Cindy Gustafson, describing the political landscape in the early days of the Tahoe Fund. Gustafson is a longtime community leader in North Lake Tahoe and the founding chair of the Tahoe Fund. Now, Gustafson represents North Lake Tahoe as a Placer County Supervisor and continues to serve on the Tahoe Fund’s board.

Lake Tahoe is at the center of many forces: two states and five counties, the Forest Service, state parks, state divisions of forestry, plus the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency, the resource conservation districts, and the many communities surrounding the lake, the nonprofits, the business owners, the developers, the second-home owners. Don’t forget the ski bums. With so many stakeholders, and so many issues at stake, the aftermath of the Great Recession made it plain that Tahoe needed a Basin-wide voice—and also a way to harness the private wealth in the Basin.

Gustafson credits the idea and the genesis of the Tahoe Fund to Patrick Wright, the executive director of the California Tahoe Conservancy.

“People saw huge untapped potential to have a private organization that would partner with public agencies to make projects happen,” Wright says. There was also potential to build unity and trust across the Basin. “Grant-making agencies love to see local matches in funding. When it comes to the [Tahoe] Fund, it also tells them the project has Basin-wide support, so you get a double benefit. You get the money, but you also get the seal of approval that matters to funders.”

Meanwhile, Senator Dianne Feinstein gave leaders in Lake Tahoe a nudge to get organized, a point she emphasized with seed money for the Tahoe Fund, donated from her husband’s family’s foundation. (The Blum Family Foundation is still at the top of the Tahoe Fund’s list of donors.) “Her political leadership was to say, ‘You have to come together,’” Gustafson says.

Wright started recruiting board members from all sides of the lake—both geographically and politically. The board of the Tahoe Fund was filled with environmentalists, government servants, developers and business leaders. It still represents that same balance of interests today. They started by finding common ground, which in this case was the lake.

“What can we agree on? We could all agree on the importance of the lake and its environment and how critical that was,” Gustafson says.

The Tahoe Fund got to work.

Work with a view along the Lily Lake Trail, photo by Bob Ward, courtesy Tahoe Fund

Expansion

In theory, the Tahoe Fund operates similarly to any philanthropic “friends of” group that is attached to an iconic landscape. In practice, the Tahoe Fund runs on a tempo of its own. Compare Tahoe with Yosemite. Both are stunning destinations. But, where one is governed by a single agency, the National Parks, the other involves many agencies. Some 4.5 million people visited Yosemite in 2019. Tahoe sees 20 million visitors annually.

A section of the Tahoe East Shore Trail is lowered by crane during construction, photo courtesy Tahoe Fund

Nevertheless, the Tahoe Fund started where many “friends of” groups work: a long list of backlogged projects. Shortly after the Tahoe Fund incorporated as a 501(c)(3), it awarded $50,000 to three projects across the lake. It helped open the new Van Sickle Bi-State Park on Tahoe’s South Shore. It provided the money to push a bike path in Tahoe City to completion. And it supported the essential UC Davis State of the Lake report, giving $5,000 to the university to ensure the science would still be published despite state budget cuts. Gustafson says the Tahoe Fund intentionally focused on “non-controversial” projects that already had consensus.

“Early on, we were often the icing on the cake. We were the last money in [for a project, and] that put us over the top so the project could move forward,” Gustafson says.

As the Tahoe Fund became more established—and as its coffers grew—it became more ambitious. In 2012, the board hired Berry as its CEO and first staff member. Her background was in marketing, and prior to the Tahoe Fund she had been working in the renewable energy industry.

“Amy is just an outstanding executive leading the organization,” Gustafson says. “We had to pick somebody we felt could communicate, could share a vision and could work well with all these organizations.”

Gustafson handed the baton for board chair to Tim Cashman, a businessman with deep family roots in Nevada. It was during Cashman’s term as board chair that the Tahoe Fund started fundraising for the Tahoe East Shore Trail, which would become its biggest project to date. The Tahoe Fund raised more than a million dollars for the paved trail, enough to leverage more than $12 million in public funding, and also provide money for long-term maintenance. The Tahoe Fund provided the money, but the project was led by the Tahoe Transportation District and was the result of a collaboration between more than 10 organizations.

“It took a lot of effort on everyone’s part, but it was a pretty easy sell,” Cashman says. Part of the incentive was to get donors’ names on plaques overlooking the lake. But also, people love trails just about as much as they love Lake Tahoe.

“When people are out on trails, they feel really good,” Berry says. “They know exactly where their money’s going and they can go experience something. And while they’re out there, they can feel a real sense of accomplishment. Like, I helped make this trail happen.”

The Tahoe Fund board at its annual dinner in 2015, photo courtesy Tahoe Fund

Leadership

As the Tahoe Fund has matured, it has also stepped into new roles. For example, comedy and marketing.

A message by Take Care Tahoe, a Tahoe Fund-financed campaign intended to bring awareness to stewardship in the Basin

To influence Lake Tahoe visitors with messaging about environmental stewardship, the Tahoe Fund hired comedians to come up with puns and one-liners about things like dog poop (“Be #1 at picking up #2”) and littering (“What happens in Tahoe shouldn’t stay in Tahoe”). Each phrase is illustrated by a cartoon. The messaging is light, but don’t be fooled by its simplicity. Behind the campaign is a much broader collaboration—40 organizations across the Basin working together to drive a big message about stewardship in the age of over-tourism. The Tahoe Fund financed the campaign, called Take Care Tahoe.

Take Care Tahoe quickly shifted its messaging in response to the pandemic. Since Memorial Day Weekend, a digital billboard on Interstate 80 has prepped visitors en route to Tahoe with a social distancing message intended to impact their behavior (“No Germs Left Behind” and “Go Big on Distance”).

Approaching its 10th anniversary, the Tahoe Fund went through a strategic planning process. Out of that process, a top priority emerged: forest health.

“If we don’t have a healthy forest, we don’t have a healthy Tahoe,” says Katy Simon Holland, who was board chair while the organization went through a comprehensive process to develop a new strategic plan.

At the beginning of March, just as the pandemic set in, Allen Biaggi stepped into the role as chair of the board. Biaggi brings with him decades of experience in public lands and perspective on Lake Tahoe. He is the former director of the Nevada Department of Conservation and Natural Resources and a former chair of the board at the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency, as well as a founding board member of the Tahoe Fund.

“There’s no one entity, no one agency, no one person that can address those big issues facing the Basin,” Biaggi says. “Nobody can do it alone. We pride ourselves on partnerships.”

Biaggi brings experience from the Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, and restoring sensitive ecosystems like Nevada’s sagebrush lands, to the Tahoe Fund’s push to invest in forest health. Recently, the Tahoe Fund launched the Smartest Forest Fund, with a goal to raise $5 million to “drive innovation” and invest in new ideas that could have a big impact. One of those ideas is an acoustic monitoring system that would make it more efficient for land managers to track owl habitat, which would help guide forest-thinning projects.

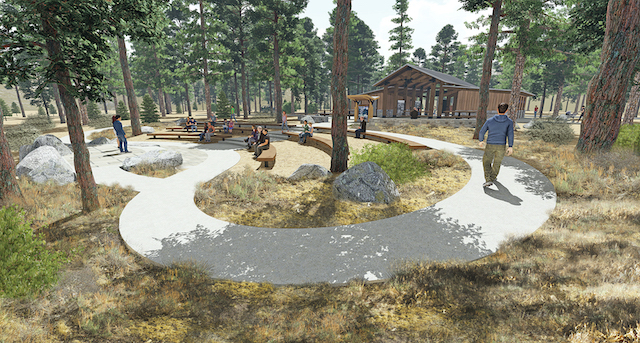

The future Spooner Lake Amphitheater, rendering courtesy Tahoe Fund

“Forest work is an ongoing effort,” Biaggi says. “It’s still a story to be written.”

The Tahoe Fund’s entrepreneurial spirit, combined with its independent voice, are going to be strengths in the years ahead, Wright says, speaking from his vantage at the helm of the California Tahoe Conservancy and as an advisory board member for the Tahoe Fund.

“It’s really positioning itself in a way that’s going to be vital to provide those critical matching funds, particularly as we move into a recession,” Wright says. “I think having private money and support is going to be more important than ever. But I also think, given the new sophistication of the organization since it’s been around for 10 years, it can do more than just provide matching funds. It can start to think more seriously, as it has been, about how philanthropic money can be used differently.

“Because as a private organization, it can be more flexible, it can be more entrepreneurial, it can take more risk than the public agencies. So, it’s got the ability to do even more in the years ahead.”

Julie Brown is a freelance writer and journalist. She grew up in Lake Tahoe and currently lives in Reno.

No Comments