24 Sep Aspens Fighting for Survival in the Tahoe Basin

The attractive deciduous tree is making a stand against the invasive white satin moth

In Tahoe, aspens are gold—both figuratively and literally.

Known for their “quaking” leaves, these trees turn striking shades of topaz in the autumn, eliciting admiration and delight from visitors and residents alike. Aside from their attractive appearance, aspens are also a rare and valuable commodity in the forests surrounding North America’s largest alpine lake.

The invasive white satin moth, in particular its caterpillar, is harming certain aspen stands in the Tahoe Basin, photo by Mark Enders, courtesy Nevada Department of Wildlife

“Aspens occur in pockets throughout the Lake Tahoe Basin and they create a really rich soil that affects everything from hydrology, the local plant community and the behavior of invertebrates,” says Will Richardson, executive director at the Tahoe Institute for Natural Science. “From a landscape diversity perspective, the aspen is so priceless in terms of what it contributes to the Basin.”

Which is why biologists and foresters have expressed increasing alarm about the invasion of a nonnative pest that has harmed aspen stands around the Basin, causing some of the oldest trees to die.

The white satin moth, native to Europe, came to Lake Tahoe about a decade ago, but it wasn’t until 2018 that its numbers exploded throughout the Basin, especially on the East Shore. The caterpillars of the moth feasted on aspen leaves so voraciously that some trees could not adequately photosynthesize due to defoliation.

The die-off at Lake Tahoe has left scientists scrambling to ascertain why the aspens in the Basin are having trouble fending off the insect, and why some trees are harmed while other individual specimens remain relatively unaffected.

Ancient Dwellers

The scientific name for the aspen tree is populus tremuloides, an obvious reference to its silver-green leaves’ propensity to tremble in the breeze. The tree was reputed among the ancients to be the best listener of all the trees because of its sensitivity to the wind, the first of all messengers.

Aspens often regenerate using suckers or sprouts from their roots to make clones of themselves, meaning that, while individual trees are relatively short-lived, aspen stands are ancient. There is a clone in Minnesota that scientists believe is 8,000 years old. As a point of comparison, the oldest known living tree, Methuselah, a bristlecone pine in the White Mountains south of Tahoe, is a mere 4,850 years old.

In Tahoe, birds like the warbling vireo and sapsucker rely on aspens for cover from predators, while other species flourish in the cool microclimate created by the aspens and their interaction with the water table.

“Aspens represent about 2 to 3 percent of the ecosystem of the forest community in the Lake Tahoe Basin Management Unit, but they support far more biodiversity than do any of our other forest upland types,” says Stephane Copetto, a forest wildlife biologist with the U.S. Forest Service.

But aspens at Lake Tahoe signify something beyond their ecological function, Copetto notes, as they play an outsized role in the human enjoyment of the natural landscape in the Basin, and the Northern Sierra in general.

“They are so beautiful aesthetically, and people appreciate them,” she says. “They serve a niche for those of us who come to the mountains in the fall to see the colors change.”

Indeed, come the first or second week of October, when the febrile height of the tourist season begins to wane, a different type of visitor arrives in the Basin, typically heading for Spooner Lake, or other aspen hotbeds, where the hues of the trees’ shivery leaves change from silvery green to brilliant gold.

Basque sheepherders left their mark in the Tahoe area with carvings on the trunks of hundreds of aspens, photo by Martin Gollery

Basque Remnants

The aspen’s role in the human drama isn’t merely relegated to providing an ideal backdrop for photographers and Instagram posters come fall. In the Tahoe Basin, the aspen trees serve as a canvas upon which an enduring slice of the region’s vibrant historical record is written.

Hundreds of aspen trees in the Tahoe region play host to arborglyphs, which are like petroglyphs but etched into the trunks of trees rather than stone. The hundreds of arborglyphs around Lake Tahoe are a testament to the lonesome lives of Basque sheepherders, many of whom settled in the Carson Valley beginning in 1860 and took their flocks up to the mountains to graze in the summer throughout the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century.

The Basque people hail from the Pyrenees Mountains between Spain and France and retain a distinct culture that defies any national boundaries. They are often called Europe’s “First Family” because of their ancient culture that predates any other on the continent. Their contributions to the New World are also significant.

The Basque people hail from the Pyrenees Mountains between Spain and France and retain a distinct culture that defies any national boundaries. They are often called Europe’s “First Family” because of their ancient culture that predates any other on the continent. Their contributions to the New World are also significant.

Many Basque sailors joined Christopher Columbus on his maiden voyage to North America. Others were among the initial pioneer trains that forayed into the untrammeled wilderness of the American West.

Before long, Basques in the West established themselves in the sheep business, with many of those who settled in the Carson Valley becoming some of the preeminent sheepherders in the region.

Summers spent in the great expanse of the Sierra appeared to have a melancholy effect on some of the herders, who carved messages attesting to their loneliness and longing for female companionship.

One such Basque shepherder carved the following into an aspen trunk in the 1920s: “Here I am bored to death. Some day the time will come to leave this place.”

That particular aspen stands on a promenade that overlooks a spectacular corner of Lake Tahoe, but clearly the view was not sufficient to allay the sheepherder’s despondent musings.

But others were more upbeat in their choice of arborglyphic subject material.

Matxin Lanathoua, a Basque sheepherder from the early twentieth century, carved many images from Basque legends into the trunks of aspens near Lake Tahoe. An image of a snake suckling sustenance from a donkey is one example among many of the bizarre elemental carvings one can encounter in the forests of Tahoe, particularly on the Nevada side.

Thus, Tahoe’s aspens are arguably the most cardinal feature of the landscape—a furnisher of microclimates, an influencer of the water table, a sanctuary for a wide array of animal species, a spectacular and colorful autumn backdrop, and a canvas upon which a slender but vibrant history is etched.

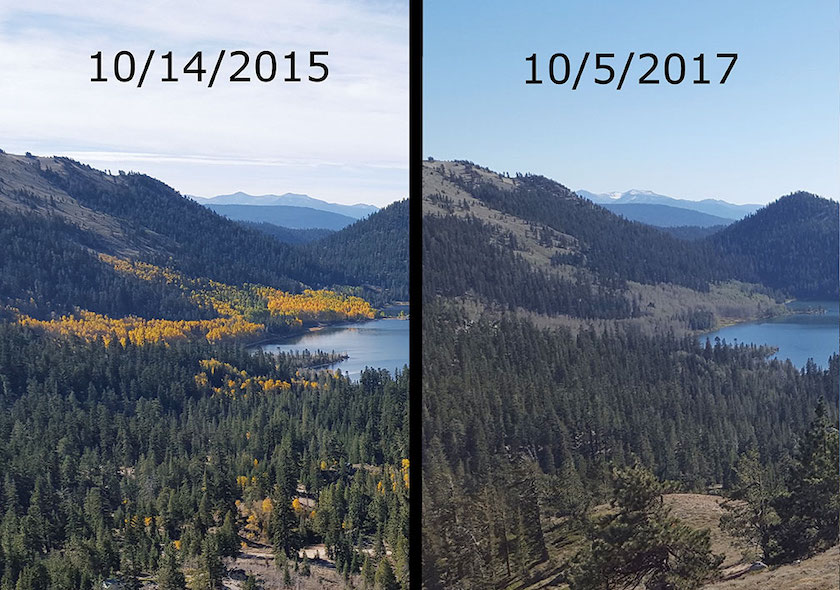

The dwindling population of aspens around Marlette Lake is apparent when comparing photos from 2015 and 2017, photo by Mark Enders, courtesy Nevada Department of Wildlife

Under Attack

For all of these reasons and more, scientists began to fret in the summer of 2017, when they noticed many of the trees were rapidly losing their leaves. In some areas of the Basin, the situation was so dire that ancient trees that had stood for a century languished and died.

North Canyon is a gully running north to south within Lake Tahoe Nevada State Park on the East Shore of Tahoe. A busy hiking trail and connector to the famously scenic Flume Trail, the area is a popular recreation destination year-round. Come fall, North Canyon boasts one of the most spectacular aspen stands in the entire Northern Sierra.

Stephanie Copetto had been active in the area for a few years, after the Forest Service had obtained federal money to undertake forest restoration projects.

Photo by Mark Enders, courtesy Nevada Department of Wildlife

“There were aspens that were dying because they were getting shaded out by the conifers in the area,” Copetto says.

The Forest Service figured by cutting back some of the impinging conifers, scientists could restore a few sickly aspen stands to a more robust condition with room to spread out.

That’s why Copetto was surprised to receive a call from Roland Shaw, a forester with the Nevada Division of Forestry, in the summer of 2018 alerting her to a massive defoliation event in a recently restored stand.

“We were seeing a die-off in trees of all ages, and I noticed there were all these caterpillars,” Shaw says. “We investigated a little further and we found out it was the white satin moth.”

The white satin moth is native to Europe but made its way to North America in the 1920s.

“They got established pretty quickly in the Northeast, but were slow to expand here,” Richardson says. “Scientists believe there was a population in British Columbia that worked their way east to Idaho and Montana and circled back to Nevada before reaching Tahoe.”

Shaw says he first noticed the critters in 2011 and 2012, but it wasn’t until the summer of 2017 that their presence reached a level at which they began to harm the trees.

Richardson says it was impossible not to notice the population boom by 2018.

“I saw moths and caterpillars all over Tahoe that year,” he says. “They cleaned off nearly every tree between Spooner and Marlette Lake. It looked like winter in the summer.”

To see such a devastating event brought on by the white satin moth was surprising because the moth, despite being invasive, does not carry a reputation for being a particularly pernicious pest. Also, aspens typically do a good job of controlling pests through a robust natural defense system. But, for whatever reason, aspens in Tahoe seem to struggle in fending off the moth.

“Aspens are fairly defenseless against these moths, it seems,” Richardson says.

The struggle is partially attributable to the caterpillars’ ability to spawn in two distinct cycles—one in June at the height of summer, and one near the end of September just before the leaves change. That means the caterpillars that eat the leaves in June are back just as the trees begin to recover.

“It’s a huge waste of energy putting out all those leaves,” Richardson says.

But even as the white satin moth has extended its range in mountainous regions throughout North America and other parts of the Tahoe Basin, including lower Blackwood Canyon on the West Shore, it’s rare to find an aspen stand that suffered as acutely as the ones in the North Canyon. The reasons for that are not immediately clear.

“One thing jumps out to me right away,” says Mark Enders, a biologist with the Nevada Department of Wildlife. “These moths really started to show up in full force after a multi-year drought that took place last decade. There is no question that aspen stands stressed by drought are much more susceptible to other types of outbreaks.”

Aspen stands in North Canyon show the effects of the white satin moth in July 2017, photo by Mark Enders, courtesy Nevada Department of Wildlife

Examining the Evidence

Scientists like Tricia Maloney, with the Tahoe Research Environmental Center, say drought is likely a contributing factor, but more study is needed before offering a definitive conclusion.

Maloney is studying the aspen leaves, particularly to see if there are differences in chemistry between the trees that do well and those that get decimated by the moth.

“One thing with aspen is that repeated herbivory induces a chemical response,” Maloney says.

In other words, aspen, which have evolved alongside all sorts of insects, including butterflies, are typically adept at emitting chemicals through their leaf structure in order to ward off feeding insects.

Maloney says understanding the chemistry in the leaf samples may provide clues as to why the aspen stands in North Canyon fared so poorly and why certain individual trees were hit harder than others.

“Certain individuals are less tolerant,” she says. “Maybe they don’t have the right chemistry.”

Richardson has a parallel theory.

“Anecdotal evidence shows that individual trees and stands that have been burned have better defenses against the moth,” Richardson says. “Maybe trees that have some scorch kicked out a chemical compound that helps.”

Copetto frets that maybe the restoration project she helmed had an unintended effect in allowing the caterpillars easier access to saplings, which led to a boom in moth population.

“I don’t think it’s true, but it’s a legitimate question you have to ask yourself,” she says.

Perhaps the answer is genetic.

“There is inherent genetic variation at play here,” Maloney says. “I would not be surprised if certain trees carry certain genotypes that create a defense mechanism that allows certain trees to go untouched.”

Others theorize that predators like wasps have discovered the white satin moth’s favorite hideouts since their explosion a couple of years ago and have begun controlling the population.

The only thing really clear at this point is that further study is necessary to achieve a better understanding of the nature and scope of the problem.

“That’s one of the problems with having an invasive species with a relatively recent arrival,” Enders says. “We don’t have a ton of information. We are more in a learning mode than a response mode.”

White satin moth caterpillars in the Tahoe Basin, photo by Mark Enders, courtesy Nevada Department of Wildlife

An Uncertain Future

But while the unknown prompts some anxiety in the scientific community at Tahoe, the good news is that 2018 appears to be the apex of the white satin moth invasion, as 2019 was not as bad.

However, the coronavirus outbreak, which has affected every corner of life in America in 2020, has made its presence felt in this particular ecological drama as well.

Maloney is concerned the funding for further tests of defense chemistry might not be there due to dwindling budgets caused by the economic recession. A few of the scientists interviewed for this story, particularly those associated with federal agencies, were not allowed into the field during June due to concerns over the pandemic, meaning monitoring has suffered.

But Shaw says he is still at Lake Tahoe Nevada State Park every day, observing the forest.

“The aspens look better this year than they have in the past,” he says. “There’s a lot of variation, of course. The lower end of the canyon looks better than the mid-portion.”

However, Shaw worries that even as the moths become more manageable, the aspen stands that are so indelible to Tahoe’s rich landscape will face other, more pernicious problems.

“The trees are more susceptible during dry periods,” he says. “With this warming trend and a pattern of more rain, less snow, and storms with more energy and more wind, we will have to continue monitoring them.”

For now, the 5-mile chain of aspens that carpets North Canyon will continue to tremble in the breeze and turn gold in the fall.

Many of the trees are poised to persist, carrying the glyphs that testify to a human history and a period of natural history that once flourished in the Tahoe Basin but has long since dwindled, leaving more uncertainty in its wake.

Matthew Renda is a Santa Cruz–based reporter and former Tahoe resident.

Pingback:These photos prove why a road trip to Tahoe in the off-season is worth it | West Observer

Posted at 05:51h, 20 February[…] nature trail and boardwalk there, visitors can browse the wetlands and learn about the region’s falling aspen population. (Apparently nimrods with Swiss army knives aren’t the only problem.) But the big surprise was in […]