27 Jan Striding The Sierra

Running deep through the Tahoe woods, outside the comforts of chairlifts, expensive lodge lunches and world-class downhill resorts, skiing exists on a different playing field.

No, this isn’t a story about backcountry skiing. This is a story about pristine tracks and desolate trails twisting and stretching through hundreds of miles of snowy Tahoe terrain. This is about a rugged man who helped pioneer a sport out of necessity and the community that has decided to keep it alive.

This is cross-country skiing in the greater Tahoe Basin.

Mark Nadell has skied the Tahoe and Truckee trails for more than 40 years and plans to continue for at least another 40. Locally, he’s known as “Captain Nordic,” having raced, coached, photographed, chronicled and fostered the future of this sport for most of his life.

“The beauty of Nordic skiing is you glide and there’s nothing, and I mean nothing in the world, that makes you feel better than when you’re gliding,” Nadell says. “Now that I’m 57 years old, I find that I can’t play basketball quite as much as I want, but I can always Nordic ski as long as I want.”

Minimal impact is just one of many perks cross-country skiers relish. The sport engages almost every body muscle, breeds endurance athletes and is relatively injury-free.

From an expense and solitude standpoint, cross-country skiing is one of the better winter options. Nordic trail tickets range from free to $30, depending on age and peak times. Rentals usually hover at about $20. There are rarely crowds, never cold chairlift rides and finding deserted trails is almost guaranteed.

But before diving into the why and where of the modern-day Nordic scene, it’s worth remembering how it all started. The story of Nordic skiing in the Tahoe Basin, and arguably America, begins with a man named Snowshoe Thompson.

Snowshoe Thompson

The nickname is deceiving since John “Snowshoe” Thompson did the majority of his traveling on ten-foot, 25-pound cross-country skis that he carved from oak.

Thompson put a lot of miles on that first heavy pair of homemade skis while serving as an unpaid mailman between Placerville and Genoa, Nevada, from 1856 to 1876. During those 20 years, the Norwegian-American braved blizzards and encounters with wolves, grizzlies and mountain lions all to deliver the mail via a 90-mile route he broke through the snowy Sierra peaks every winter.

Despite the frigid temperatures and dangerous wildlife, Thompson didn’t carry a gun or blanket. The goal was to save weight on personal items and carry as much mail as possible. His postal sack usually weighed in at nearly 100 pounds, stuffed to the brim with supplies for others as well as letters and other correspondence, according to Friends of Snowshoe Thompson, a nonprofit dedicated to preserving Thompson’s story.

Two to four times a month, Thompson would don a thick mackinaw jacket, cover his face in charcoal to prevent snow blindness, strap on the heavy pack and charge out on skis.

He didn’t rest often. Thompson only stopped when the weather turned especially nasty. Then he dug out a rock from the snow to do Norwegian folk dances on and stay warm. He rescued many prospectors in distress on those chilly nights by carrying them out on the back of his skis.

The U.S. Postal Service never paid him, although he went to Washington D.C. in 1872 to try and collect, according to Friends of Snowshoe Thompson. Legislators ignored him and he returned to the Sierra empty-handed.

He died in 1876 after appendicitis developed into pneumonia, but his legend of cross-country lore lived on through the decades.

“In 2001, three young men from Reno retraced Snowshoe’s route from Placerville to Genoa on modern cross-country skis,” says Sue Knight, who works for the nonprofit. “It took them six days compared to Snowshoe’s two to three days.”

Dan Hill enjoys perfect classic ski grooming in the meadows of Tahoe Donner’s Euer Valley trails, photo by Mark Nadell

A Nordic Hotbed

Cross-country skis have come a long way since Thompson’s early 25-pound pair, and so has the Tahoe Nordic scene.

Downhill ski meccas, like Tahoe, are not always synonymous with strong cross-country communities. Creating a thriving Nordic community takes more than just annual snowfall. But cross-country skiing is alive and well in the Basin, particularly on the North Shore and Truckee, which boast wonderful groomed Nordic trails.

“Between Tahoe Cross Country, Tahoe Donner Cross-Country and Royal Gorge, we have a lot of really good groomed trails,” Nadell says. “Those three are basically world-class ski resorts and they’re all within a 30-mile radius.”

There are about 465 cumulative kilometers of groomed trails among those three cross-country resorts. Royal Gorge in Soda Springs lays claim to the majority of those trails, about 300 kilometers, and is known as North America’s largest cross-country ski resort.

Tahoe Cross Country is a nonprofit, community-run organization with 65 kilometers of trails located in Tahoe City. The center is a big part of North Shore cross-country growth, offering free or minimally priced youth education programs and clinics to community members.

Tahoe Donner Cross-Country in Truckee boasts 100 kilometers of groomed trails and night skiing once weekly.

While the South Shore Nordic scene is not quite as prevalent, a new nonprofit network of trails at Lake Tahoe Community College could change that.

The Lake Tahoe Community College Nordic Club will open about 5 kilometers of groomed Nordic trails on campus this winter. Day passes will be $5, and trail organizers hope to incorporate a youth cross-country program at the center.

Tyler Cannon, owner of Sprouts Natural Foods Cafe, is a driving force behind the new trails. He originally planned to have the trails up and running midway through last season, but low snowfall hampered the effort.

“The plan is still the same, but now everything is set up so even if we only get six to seven inches we’ll still be able to run trail,” Cannon says.

Hope Valley Outdoors, 40 kilometers, or Kirkwood Cross Country and Snowshoe Center, 80 kilometers, are located off Highway 88 and the nearest Nordic centers with more advanced terrain.

The ample amount of groomed trails in Tahoe would already be enough to foster a flourishing cross-country community, but those resorts are just the beginning. There’s also a packed race schedule on the North Shore.

The Far West Nordic Ski Education Association schedules a cross-country race nearly every weekend in the winter. The races are open to skiers of all ages and ability levels.

The most “user-friendly” races, as Nadell puts it, are the Snowshoe Thompson Classic at Auburn Ski Club on December 22, the Sierra Skogsloppet at Tahoe Donner Cross-Country on January 20 and the Alpenglow Freestyle at Tahoe Cross Country on January 26. The Gold Rush race will also return to Royal Gorge this year after a brief hiatus.

Two longer, more challenging options are the Tahoe Rim Tour on February 9 and the highly-anticipated Great Ski Race on March 2.

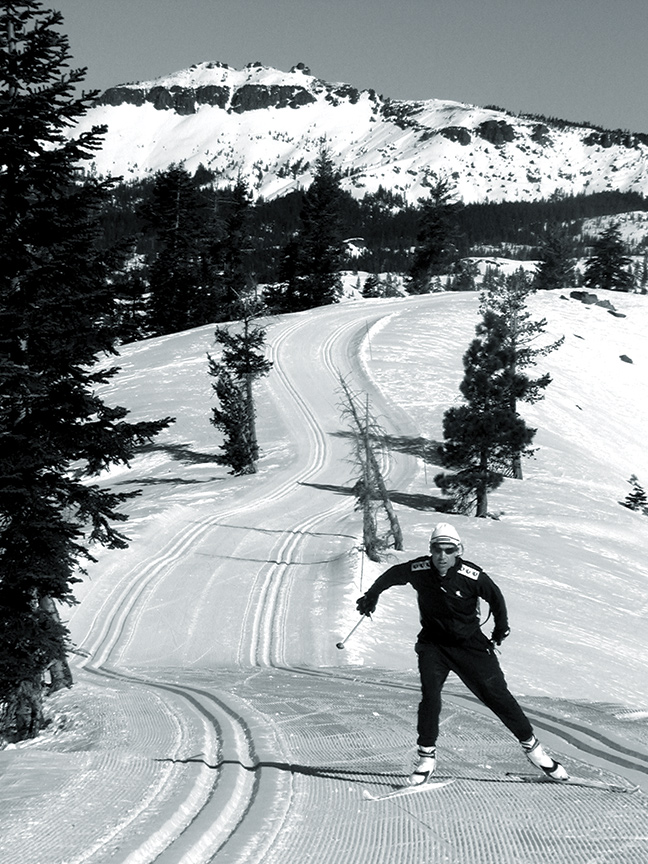

Sugar Bowl Academy Nordic Coach Jeff Schloss enjoys the breathtaking views of Castle Peak on the Razorback trail at Royal Gorge XC Area.

The Great Ski Race

The area’s lore of Nordic skiing is perhaps most obvious at the Great Ski Race.

The race started in 1977 with 60 skiers, who were manually timed, and quickly developed into national event. By 1985, the race bumped its numbers to 600. In recent years, participation hovers closer to 1,000, and the Great Ski Race is now known as one of the largest Nordic ski races west of the Mississippi River.

The 30-kilometer course starts at the Tahoe Cross Country Center in Tahoe City and ends at the Cottonwood restaurant in Truckee. Along the way, there are 1,200 feet of uphill and 1,800 feet of downhill, which includes a gritty final downhill known to produce crowd-pleasing wipeouts across the finish line.

Nordic skiers of all levels, from Olympic-caliber speedsters to costume-clad weekend warriors, have found themselves brushing off snow at the finish.

While the Great Ski Race is by far the most popular, there are 25 races scheduled in the North Shore and Truckee this winter.

“I don’t think there are a lot of areas like ours that have all these great options available,” says former Olympic biathlete Glenn Jobe of Sierraville. “We have lots of snow, but we also have sunny days and you add in these great cross-country areas to choose from and it’s just excellent wherever you go.”

A Nordic legend

The local race scene is actually where Jobe’s Olympic journey really began.

Jobe never planned on trading in his downhill skis for cross-country. He lettered in alpine skiing at the University of Nevada, Reno, in 1971–72. Alpine racing was a nice change from the ranch life that Jobe was accustomed to in Alturas, California.

But when the next season rolled around, the alpine team was packed while—big surprise—the Nordic team needed applicants.

Jobe already ran cross-country, so he decided to give skis a try.

“I liked the whole idea of endurance,” Jobe says. “I still liked alpine skiing, but cross-country just seemed like it would be a natural fit for me.”

And it was. He started doing well in races, and decided to stick with his new Nordic outlet after graduating in ’74. Once out of college, however, the competition level picked up. Jobe was hitting a wall, but he kept on racing.

It was during one of those races that Jobe met a biathlon coach from Jackson Hole, Wyoming. The coach was intrigued when he learned Jobe grew up on a cattle ranch and knew how to shoot. He invited Jobe to a Jackson Hole biathlon camp.

“So I went to the camp and it was just a good fit,” Jobe says. “The two sports seemed to go together for me. I liked everything about the sport. I like the challenge of it, both mentally and physically, so I just decided at that point to focus on biathlons and see how far I could get.”

Jobe gave himself five years to reach the Olympics.

He went to the Olympic trials in ’76. But with only one season of biathlon experience under his belt, he didn’t make the cut.

Jobe went home and dove into training. He hit the tracks at the cross-country resort he had founded and now owned at Kirkwood Ski Resort. In October, he trained at an Olympic training center formerly housed at Squaw Valley.

In 1978, the hard work paid off and Jobe made the world championship team. He was on pace for the 1980 Olympics. The following year, he made the team again, and by the age of 28 he cemented a spot on the Olympic roster.

“It’s out there. If you make up your mind to do something and pursue it you can achieve a lot,” Jobe says. “I wouldn’t trade it for anything. It was a great journey and fun to achieve a goal.”

1980 U.S. Olympian Glenn Jobe demonstrates prone shooting technique at Auburn Ski Club’s Biathlon Range

Fostering a Nordic future

Both Jobe and Nadell don’t expect cross-country skiing to explode overnight.

“We’re still a tiny, tiny niche in the big scheme of things,” Nadell says. “And we will probably always be a niche sport because one, it takes a lot of physical exertion and two, it’s not something you can generally do out your door like you can with biking and running.”

The sport is growing, slowly and steadily, like any cross-country journey—and it’s starting at the bottom.

Nadell coaches the Nordic team at Alder Creek Middle School in Truckee and says most junior programs in the area have doubled in size this past decade despite shrinking school enrollment numbers. Why?

In large part, the beefed-up junior programs are a result of coaches like Jobe and Nadell who are supported by organizations like the Far West Nordic Association and the Auburn Ski Club. These junior programs are producing more and more competitive Nordic athletes and gaining national acclaim.

It was the Auburn Ski Club that picked up Jobe’s biathlon program when Northstar California dropped the clinic two years ago. The private Nordic club recently added a permanent range for the biathlon program and hosted the Summer Regional National Championships.

“There is definitely an increase right now in the talent coming up through the Tahoe area,” Jobe says. “Several of our cross-country skiers are on university ski teams. Several athletes are on the Olympic development team. There are young kids in the biathlon program that show tremendous talent. There’s a lot of local talent coming up.”

The next Glenn Jobe could already be out there, whipping down Tahoe’s trails.

Former University of Nevada, Reno XC Ski Team member Emma Garrard

firing at the 10th Mountain Division Biathlon race at Auburn Ski Club in 2008

No Comments