27 Sep Of Mysis and Men

UC Davis published its annual State of the Lake report this summer, highlighting a massive drop in non-native shrimp—so now what?

Brant Allen’s three-month stint at Lake Tahoe has lasted 34 years so far.

After graduating from UC Santa Barbara with a marine biology degree, Allen was looking for short-term jobs in freshwater fisheries. He ended up taking a temporary position at a picturesque alpine lake shared by two states, and he’s been with UC Davis ever since, working as a staff researcher who regularly heads out onto Lake Tahoe for monitoring.

Joining with two or three colleagues, he typically motors the research vessel John Le Conte—an old 37-foot diesel-powered salmon trawler—out of Tahoe City Marina at around 8:30 a.m., drives to their designated site, collects samples and finishes around 4:30 p.m. If there’s night-based collecting on the schedule—as is necessary when counting mysis shrimp, which were introduced into the lake as potential food for game fish in the 1960s—they depart before dark and work for roughly six hours.

Over Allen’s more than three decades of routine collecting at all hours, he says he’s never hauled out anything he would consider anomalous: “It’s not like I’m pulling up bodies or diamond rings or strange fish or anything like that.”

This past year, however, something caught his attention. It wasn’t a mysterious object or creature. In fact, the something wasn’t anything at all. Allen was surprised by what he didn’t see in his samples.

“Starting in early January of this year, we noticed the shrimp populations had declined dramatically,” he says.

That decline continued through the winter, into the spring and beyond. Normally they’d collect about 100 mysis shrimp in a net when they took samples in the summer. Instead, they were seeing two or three.

Mysis numbers swell to more than 60 billion in Lake Tahoe when they’re doing well—and the miniscule crustaceans are often doing well. They enjoy a constant all-you-can-eat buffet of the lake’s natural zooplankton, but manage to stay mostly off the menu themselves since they spend their days in deeper waters, below where their intended predators like to cruise. Ascending at night, they dine, reproduce and repeat in virtual safety.

As of 2022, however, less than 3 billion of the tiny creatures are estimated to live in Lake Tahoe.

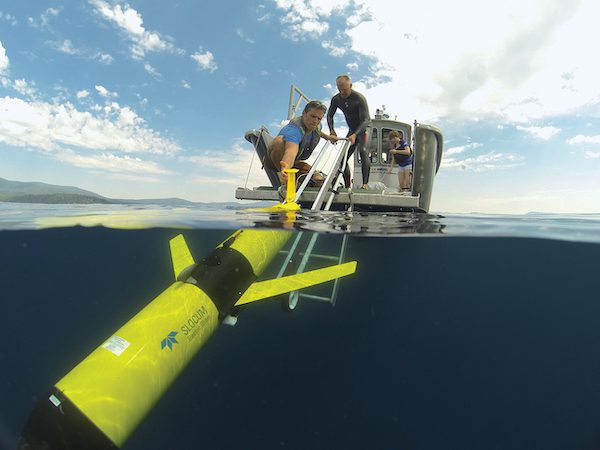

As part of a Tahoe Science Advisory Council study, Brant Allen and Alex Forrest launch an underwater glider to map the distribution of lake water quality variables, courtesy photo

Where are the Mysis?

The fact that 57 billion creatures seem to have vanished from an environment where they have mostly thrived since their arrival is—as Allen puts it—“interesting.” It’s not just adults that have disappeared, he explains, but every age of shrimp, right down to the babies.

This mysis crash is potentially good news for the daphnia of Lake Tahoe, which are microscopic “water fleas” that have two primary characteristics: They indiscriminately filter everything from algae particles to floating bits of clay out of the water as they feed, and they’re a meal of choice for mysis shrimp.

Since a daphnia life cycle is short—especially when compared to the three-year turnaround for mysis to reach reproductive maturity—there’s a chance the daphnia population can rebound while the shrimp are rallying their own numbers.

What that means for other creatures in the lake, as well as other variables including everything from algae levels to water clarity, remains unknown—as does the reason the mysis are missing.

Is the plummeting mysis population linked to a massive zooplankton die-off that happened the prior November? In other words, did the shrimp starve to death? And was that initial zooplankton die-off the result of weeks of wildfire smoke blocking light that would have otherwise nourished algae last summer?

“Seeing a lake change ecologically in a relatively short period of time is … I would call that extremely unique,” Allen says. “… I can’t think of another time in my time frame here when there’s been a shift that happened that quickly.”

For Allen—and dozens of other researchers whose work was summarized in the “Tahoe: State of the Lake Report 2022”—there are no answers yet. Data is still being analyzed. Numbers are still being crunched. And Lake Tahoe continues to serve as a 40-trillion-gallon crucible for whatever experiments happen as a result of nature intersecting with the people who live, work and play in the area. The complexity of these interactions coupled with the size and complexity of the lake itself can make finding answers a difficult challenge, but there are clues to be found for those who know where to look.

Echoes of the Past

Geoffrey Schladow, director of the UC Davis Tahoe Environmental Research Center, explains that a similar mysis crash happened around 2011, but the population drop was confined to Emerald Bay. After the shrimp disappeared, he says, native microscopic zooplankton numbers improved significantly—and so did the water clarity, by 20 or 30 feet. The daphnia were back and doing what they do so well: According to the State of the Lake report, just one daphnia can eat 100,000 fine particles per hour.

Schladow describes the Emerald Bay event as a “beautiful five-year experiment,” and it has given researchers some indication of what to expect in the near future. He cites “probably the best summer clarity readings we’ve had in 20 years,” noting that clarity during Tahoe’s busy summer season has measured at 50 or 55 feet in recent years, but now measures at more than 70 feet every time they go out.

These findings come on the heels of a 2-foot decline in average annual clarity, from 63 feet in 2020 to 61 feet in 2021, according to the State of the Lake report, which highlights a disturbing observation that Tahoe’s waters show “no pattern of consistent clarity improvement over the past 20 years.” The report notes that the lake, as of 2021, had not fully recovered from a spike of fine particles that flowed into its waters during the extremely wet year of 2017.

Moving forward, if the daphnia indeed return in robust numbers in the absence of the mysis shrimp, some researchers expect clarity to continue to improve in 2023.

But diamond-clear water isn’t forever.

Around 2014, once the mysis started taking over again in Emerald Bay following the 2011 crash, the daphnia numbers dropped along with clarity. Similarly, the mysis will likely stage a comeback at some point.

“It’s almost impossible to get rid of something entirely from a lake or any biological system,” Schladow says.

More than Mysis

The disappearance of billions of tiny shrimp is just one oddity among several that UC Davis researchers have noted in the past year.

Schladow says many variables in the lake have stayed more or less the same for a while—nutrients, temperatures, clarity, etc.—to the point that he thought he would have to stretch to say something interesting about the most recent State of the Lake.

Algae has become increasingly common on Tahoe beaches in the past year, courtesy photo

Instead, biological factors changed dramatically. In opposition to the mysis decline, free-floating algae in the form of phytoplankton mysteriously exploded. Algae growing on rocks at the edge of the lake also flourished, as did algae stimulated by Asian clams, washing up on beaches and disgusting visitors.

“Kids swimming are coming up covered in green algae,” Schladow says, adding that the issue worsened in the late summer.

Overall, he admits that these seemingly dramatic events could be a warning sign of something, but he prefers to think of them as an opportunity. When there are big changes, Schladow explains, it’s easier to measure those changes, which can make it easier to put together an explanation for what’s happening and why—and there are people who want that information.

Tahoe has a $3 billion annual tourist-based economy, Schladow says, and people don’t like what they’re seeing on the beaches.

“We get phone calls every day … from people wanting to know, ‘What’s happening? Is it dangerous?’” Schladow says.

There are mitigations that can be made, but Schladow says his team is still collecting long-term data, still seeking funding for further mysis studies and algae investigations. And in just a few months, they’ll have the data that will go into next year’s State of the Lake report. It’s an ongoing endeavor.

“If you get to work in Antarctica, you realize you’re among a few people who work there,” Schladow says. “At Lake Tahoe, it’s the same. It’s a unique system. It’s the clearest high-altitude large lake in the world. And it’s changing rapidly for things we have little control over, like climate change.

“So I think what excites me is having the opportunity, the privilege even, to be able to work here, to have the resources—meaning, the funding—to work here, and to be able to assemble a team of people who can feel exactly the same way.”

Ryan Miller is a writer who lives in the Sacramento area. Follow him on Twitter or Instagram, @jesteram.

No Comments