23 Feb Bay to Bay

How Lake Tahoe’s early conservationists changed the world

During the Gold Rush era, pioneer geographers stubbornly penciled in a mythical river linking Lake Tahoe to San Francisco Bay. Of course, no such river exists. Yet, in the battle to save the planet’s lakes, bays and beaches from destruction, Lake Tahoe and the Bay remain forever linked. That’s because, viewed from a global perspective, no two bodies of water anywhere on earth have done more to protect planetary water quality than Lake Tahoe and the San Francisco Bay combined. In this sense, our beloved Lake Tahoe really does “flow to the Bay” after all.

Early Activism

In both cases, it started some 50 years ago when two separate groups of amateur kitchen-table activists set out to change the world—and did.

The first group was the nascent League to Save Lake Tahoe, originally founded in 1957 as the Tahoe Improvement and Conservation Association. Its goal: to block plans to build enough high-rise casinos, landfill marinas and shoreline freeways—including four-lane concrete bridges spanning Emerald Bay—to turn The Lake into a high-altitude sewer.

The second group was called Save the Bay. Formed in 1961, it fought to stem the flow of raw sewage and untreated industrial effluent directly into the San Francisco Bay; it also blocked landfill plans that would quite literally have buried more than two-thirds of the Bay forever—leaving little more than a narrow seagoing sewer.

Today, such plans sound ludicrous—as unthinkable, it seems, as that mythical river pictured on pioneer maps connecting Lake Tahoe to the Bay. Yet, the sheer fact that such plans sound so ridiculous is ample testimony to the courage, vision and dogged determination of those early activists and their little shoestring conservation organizations. Together, they helped turn the tide of American public opinion so completely that now most folks under the age of 50 can scarcely believe there ever was such a danger to San Francisco Bay or Tahoe’s beloved Emerald Bay.

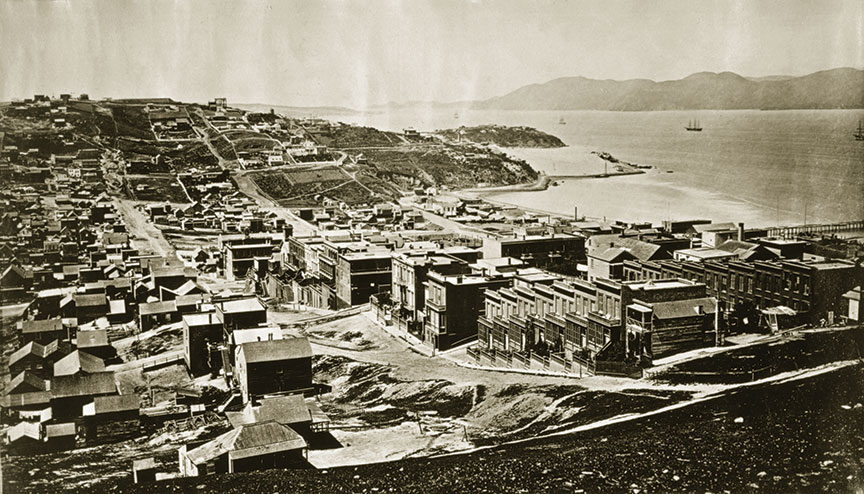

Looking out the Golden Gate, a view of the San Francisco Bay, circa

1860-1870, photo courtesy the Society of California Pioneers

Watershed Moments

Those early triumphant successes did not just stop at the shoreline—or the border. Instead, their influence on national water policy soon became truly international in scope, triggering a global tsunami of water-conservation legislation worldwide.

In 1969, California—then governed by future President Ronald Reagan—entered into the bi-state Tahoe Regional Planning Agency (TRPA) compact with the State of Nevada to protect the high-alpine lake environment through land-use regulations. TRPA, ratified that same year by Congress, became one of the first U.S. watershed-based regulatory agencies.

The first wave of watershed legislation at the national level culminated in passage of the landmark U.S. Clean Water Act of 1972. In effect, by protecting local watersheds, it triggered a watershed reversal in American conservation history.

Skeptics take note: This occurred at the height of the Nixon Era. Yet, that was also an era in which an energized American public—from Republicans to Democrats to Independents—rallied around a truly bipartisan consensus strong enough to propel the Clean Water Act straight through Congress and onto a Republican president’s desk for his signature.

The tsunami of change continued globally: Inspired by the spectacular recovery of Lake Tahoe (and similar improvements to the health of San Francisco Bay), visitors from around the world went home determined to clean up their own lakes, bays, rivers and shorelines—demanding their governments pass Clean Water Acts of their own. If Nevada and California could cooperate to protect clean water, they wondered, then why can’t we? And so within a decade, France and Switzerland joined hands to save Lake Geneva from choking levels of pollution, and even in Russia—as the Soviet Union collapsed—scientists and politicians stepped up to help apply Tahoe’s lessons to Lake Baikal, the world’s largest freshwater lake, Tahoe’s big brother, containing an estimated 24 percent of all the Earth’s fresh water.

From Tahoe to San Francisco Bay and beyond, the basic blueprint for success remained the same: Fractious political boundaries and local biases must be set aside in order to protect an entire watershed as one. Much as the famous conservationist Aldo Leopold once urged us to “think like a mountain,” stakeholders have learned to “think like a watershed” instead.

These days, both Lake Tahoe and San Francisco Bay find themselves imperiled by a whole new series of globalized threats, ranging from climate change to planetary air pollution to invasive species. To put it bluntly, the future citizens of China and India may play a greater role in Keeping Tahoe Blue than we do; saving lakes and bays is no longer just a local matter.

Which is precisely why we need to keep proudly celebrating—and actively exporting—our treasured local history of cooperation, compromise and creativity. Because for all our endless battles and bickering, Tahoe and the San Francisco Bay together still remain the global gold standard for saving large bodies of water worldwide. Our big blue lake and our little blue planet are ecologically linked. As Tahoe’s leading lake scientist, Dr. Charles Goldman, told us decades ago, “If we can save Lake Tahoe, we can save the world.”

Let’s make sure slogans like “Keep Tahoe Blue” and “Save the Bay” remain a rallying cry not just locally, but globally, for decades to come. Because from Russia’s Lake Baikal to Europe’s Lake Geneva, and from South America’s Lake Titicaca to Africa’s Lake Victoria—and yes, even by the shores of our own Lake Superior here in the U.S. and Canada—the lessons from the fractious cross-border disputes that once threatened Tahoe’s survival can be applied to the world’s “other” Great Lakes as well.

View from the top of Cave Rock, on Lake Tahoe’s East Shore, looking north,

circa 1860-1870, photo courtesy the Society of California Pioneers

Scott Lankford, a professor of English at Foothill College, published the 2010 book Tahoe Beneath the Surface: The Hidden Stories of America’s Largest Mountain Lake.

No Comments