27 Sep A Ride of a Lifetime

Andy Finch receives his due recognition more than a decade into retirement as the snowboarding world reflects on his hard work and hard-charging style

On February 12, 2006, Andy Finch stood atop the halfpipe in Bardonecchia, Italy, a snowy village about 90 miles west of Turin, Italy, home of the 2006 Winter Olympics. Finch, competing against 43 of the best snowboarders from around the globe in the men’s halfpipe, took a few deep breaths, girded himself in front of the crowd of 30,000 and slid down onto the lip, over the edge and briefly vanished, only to reemerge on the other side.

He soared.

And then, he came crashing back to earth.

For a few short moments, Finch, the Truckee-based kid originally from Fresno, became the embodiment of the Olympic motto: “Citius, Altius, Fortius” (“Faster, Higher, Stronger”). Nobody on earth could go higher, tweak their airs with more style and, as fate would have it that day, hit the deck harder.

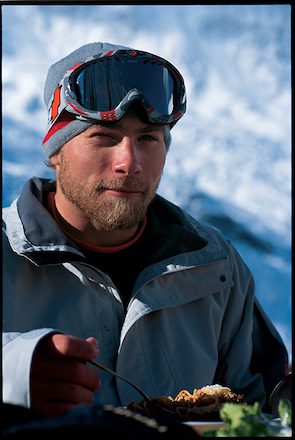

Andy Finch fuels up with some spaghetti bolognese in Saas-Fee, Switzerland, in 2003, photo by Sean Sullivan

Though riding on an injured foot, Finch was on a once-in-a-lifetime mission and managed a 43.1 on his opening qualifying run, good for fourth place and a guaranteed spot in the final for a chance at a medal. But that’s when it came to an end.

A fall on his first finals run aggravated the foot and a fall on the second run—while boosting arguably the biggest air of that Olympic Games—did him in for the day, landing him with the most significant injury of his career, and a 12th-place finish.

“I had really strong bones,” Finch says with a laugh as he recalls that day, and others to follow, from his Truckee home. “The only bone I ever broke was my wrist at the Olympics.”

As he watched teammates and friends Shaun White (gold) and Danny Kass (silver) ascend the podium, Finch—who came home from Torino wearing a souvenir cast on his forearm instead of hardware—was circumspect, and grateful: “I did, like, maybe two tricks total for three runs, but mostly I just ran straight airs and cold turkeyed on the final run,” he told the Sierra Sun upon returning from Italy. “It was amazing because even without the tricks, I still was in the top 12 qualifiers.

“The key to the whole Olympic experience for me was the people, and they were all just great. I felt honored to be a part of it all.”

Fast forward 18 years and Finch, now 43, still feels the same way about the experience. No regrets for riding as hard and as fast and as high as he could—but also, truth be told, he felt he had no choice in the matter.

“I knew I had a niche: I love to fly,” Finch says. “I also knew people enjoyed that that’s the one thing that would make me stand out in the crowd. And to me, if I could stand out, I could make it as a snowboarder.”

Finch isn’t exaggerating. It’s telling to watch old clips of him on YouTube and see that he’s just going a little bit bigger than everyone else. But when things went wrong—and they did—he came down hard.

“When he’s dropping into the halfpipe, everyone stops what they’re doing,” says Truckee-based pro snowboarder Tim Humphries, recalling his early days watching Finch. “Everyone just stops and watches. He did not hold back. The guy is an absolute lunatic. He’s so insane.”

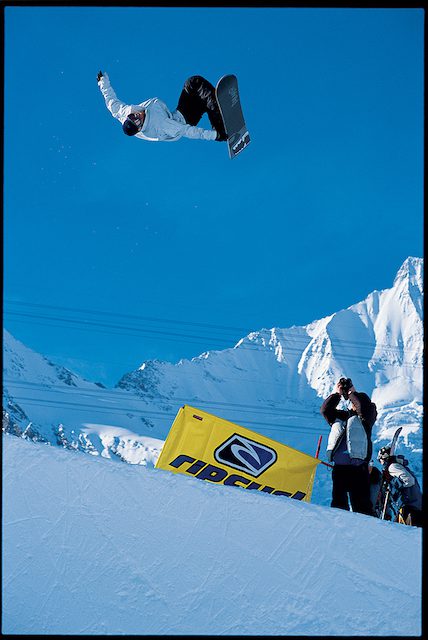

Andy Finch with a massive air at the Arctic Challenge in Norway in the early to mid 2000s, photo by Frode Sandbech

‘So Much Energy and Power’

Finch first stomped onto a snowboard deck at age 12 on the family-friendly slopes of China Peak (then Sierra Summit), located in the Central Sierra about 70 miles outside of Fresno. He decided right then and there that’s what he wanted to do with his life.

“It was never a question,” Finch says. “When I saw a snowboarder make it look stylish and good, from that point on it was what I was going to do. That was it.”

While millions of kids might have had similar thoughts, Finch was the one who turned them into reality.

“I had a lot of heart. Probably had more heart than talent and natural ability,” Finch says. “I dreamed big and had a lot of determination. But I’m glad I didn’t know what I know now. It’s almost like I had the benefit of having to work so hard to make it; those life lessons would carry me through.”

The lessons, and the success, came fast.

Part of the last generation of multi-disciplinary riders, Finch landed his first board sponsor in 1997 at age 16: Palmer Snowboards, teaming up with notorious South Lake Tahoe multi-sport athlete Shaun Palmer, whose “bad boy” reputation was juxtaposed directly to Finch’s squeaky-clean aesthetic.

“Palmer once told me there’s no such thing as bad marketing,” Finch says with a laugh. “I was always blown away by his generosity and how he made tough decisions—and some of those kept him from excelling. But he’s still doing it, there’s still a smile on his face and he’s very much the unique, original guy he is.”

By 1998, only five years after strapping in for the first time, Finch was a bona fide pro. He proceeded to win the 1999 U.S. Junior Worlds in boardercross, but he didn’t enjoy his place at the top of that discipline long before shifting his focus to the halfpipe and finding similar success there.

“I have a ton of thoughts about Andy,” says Bob Klein, one of Tahoe’s pioneer snowboarders of the late 1970s and Finch’s manager in the early 2000s. “I’ve known him since he was 16. Andy just crushed it at boardercross. He was this happy-go-lucky kid, super excited to be a part of anything. He just rode with total explosion. Everything he did had so much energy and power. It was a privilege sponsoring him and representing him, as well as developing a longtime friendship.”

Finch at a 2002 U.S. Snowboard Team session at Mammoth Mountain, photo by Sean Sullivan

When Finch switched disciplines to halfpipe, Klein says he immediately turned heads with his aggressive style, especially among his competition.

“It was a really interesting time in snowboarding,” Klein says, explaining that technical tricks combined with big airs were pushing the sport into an age of innovation. “Andy, he came in at this time they were really progressing snowboarding. The reflection of that was ’02. I represented Danny Kass as well. Danny was conflicted because he was so technical, but he wouldn’t go as big. He was 5, 6 feet out of the [pipe], where Andy was 12 feet out. It was where power and technical tricks kind of met—and Andy took it to the next level.”

Arguably boosting out of the halfpipe higher and stronger than anyone had before him, Finch won the World Cup title in Japan in 2002, missed making the U.S. Olympic Team that year by a single point and then went on to dominate the U.S. Grand Prix halfpipe in back-to-back years, winning overall titles in 2003 and 2004. Also in 2004, Finch won both the Vans Triple Crown and Arctic Challenge in Norway—started by Terje Håkonsen and Daniel Franck—and placed second at the Vans Tahoe Cup at his adopted home mountain, Northstar.

‘Running Out of Spare Parts’

Finch’s career continued to soar, through the 2006 Olympics and years to follow, and while he didn’t always hit the top of the podium, “He always, always was the guy who everyone looked up to, literally,” Humphries says, while admitting there’s a hidden cost to it all—a fact he knows well as a former competitive snowboarder himself.

“A lot of the contest riders go through the meat grinder,” Humphries says. “And for you to continue to learn these new tricks, your body can’t quite recover … then a young, hungry kid built out of rubber—their baseline starts where you progressed to. Injuries stack up and everything, well, it starts to go.”

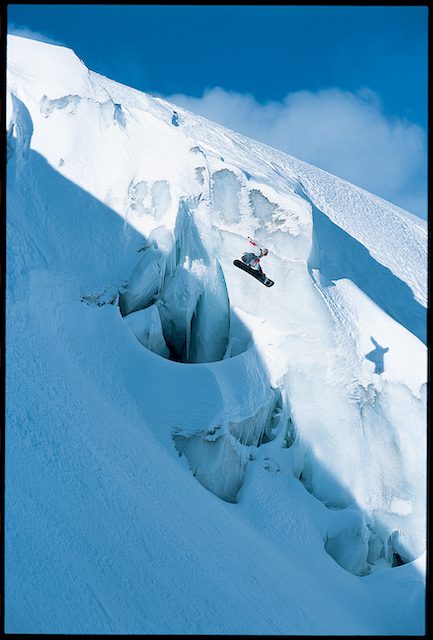

Andy Finch floats above the halfpipe during a 2003 Rip Curl photoshoot with Sean Sullivan and Brad Holmes in Saas-Fee, Switzerland, photo by Sean Sullivan

That moment came for Finch at the final stop of the U.S. Snowboarding Grand Prix in January 2010.

Arriving in Park City, Utah, it was already an emotional moment for Finch and the snowboarding world at large. Just weeks prior, friend and fellow pro rider Kevin Pearce hit his head on the lip of the Park City halfpipe—ironically, the same pipe where Sarah Burke was killed in 2012—attempting to learn the new trick that everyone wanted in their quiver, the double cork.

Pearce was hospitalized in critical condition and suffered severe brain damage. While he survived and continues to share his story as a motivational speaker, a line had been drawn.

Finch came into the Grand Prix not having the double cork in his repertoire but knowing that, to have a chance at making the 2010 Olympic team, he’d have to figure out a way to get there.

“I kind of had a shot at it at more of a distance because of the double,” he says. “But I knew my body couldn’t go through the beating anymore, because things were starting to break and at a certain point you’re not as tough as you used to be. I saw that writing on the wall. You [have to] make a decision to push to a point where you don’t ever come back, and I was getting to that point.”

On the second day of training, Finch’s fate was decided for him. He returned home that afternoon after landing hard on his shoulder. He and his wife Amber sat down and talked it out.

“It was a huge turning point in my career with shoulder surgeries. You can only be stretching out soft tissue so much before it loses its integrity,” Finch says. “Eleven months out of a shoulder rebuild, and I knew what it meant. I started running out of spare parts.

“That was my last halfpipe contest.”

Even though Finch switched disciplines again—this time to big-mountain riding—the recession led to even more major life decisions off the mountain.

“With the change in my direction in my career and my sponsors, whether it was the competitive side or the media side, it started to slip away,” Finch says. “A couple of sponsors went into hiding because of debt collectors. By the time 2011 hit, I lost every single sponsor.”

Legendary snowboarder and photographer Mike Basich shows off his airtime camera follow skills as Finch throws a one-footer over a 60-foot jump, photo by Mike Basich

Impeded by Image

Finch’s legacy has taken a long time to take shape since then. As the narrative goes, reigning snowboarding GOAT Shaun White and technical trick specialists like Kass got much of the credit for bridging the gap in the sport between the old world of floaty, style-drenched, skateboard-inspired tricks in the halfpipe to what it is today: an analytics-driven, heavily choreographed, locked-in lesson in acrobatic and gymnastic feats where precision, rotation and flawless execution are not just the keys to success, but barriers to entry.

In some ways, Finch in his prime was hampered by his image—whether it’s because he was a geographic outsider to the sport (coming from Fresno), or because his riding style was influenced by his wakeboarding background (he was a sponsored wakeboarder as a teen), or even because of his unabashedly professed Christian faith. None of it fit the mold of a typical pro snowboarder image.

As a result, Klein says, the industry was reluctant to place Finch among snowboarding’s elite, even if he was one of the biggest influencers and pushers of the sport.

“Andy, you know, it was a major struggle to get him contracts,” Klein says. “Every single one of these team managers were washed-up, never-was, wanna-be pro guys, and were like, ‘I’m in charge. I can pick who I think is cool!’ And in many cases, I had conversations with these douchebag team managers and whether it was [his] ‘bad’ style or being outgoing religiously, in those circles, he wasn’t a cool guy. Didn’t have the look. Didn’t have the style. And he didn’t kiss their ass, either.

“I thought we were a good match, because he was so positive and so kind, and so forward-thinking. Andy figured out a way to make it work financially and time-wise and dedication-wise. He’s one of the hardest-working riders of that era.”

Leading by Example

Hindsight might be even more forgiving to Finch’s legacy, Klein says, noting that he and many of his contemporaries now embrace a new line of thinking: one where Finch—who showed what was possible with his sheer amplitude—is now a key figure in snowboarding’s progression.

Finch is emerging as the sport’s living missing link.

Finch with an icy cliff drop in Saas-Fee, Switzerland, in 2003. As Finch recalls: “It had some size to it and the locals were shaking their heads at us because of how dangerous it was to be riding in that area. Sean had a great eye for this one,” photo by Sean Sullivan

“My first memories of Andy were just watching him in the halfpipe: He rode like a pit bull, so aggressive and explosive,” says former Tahoe-based pro snowboarder and 2014 Olympian Chas Guldemond. “This is like 2005-’06. I was just on the cusp of making it onto the scene myself. I remember going to the events—I wasn’t invited to them yet—and I just remember him skying overhead tweaking his board so hard it turned into a banana.”

Guldemond says Finch and the generation of riders who descended on Truckee to film and compete just before his time inspired him to pick up and move across the country from New Hampshire, sight unseen, to try to make it—something, he says as he laughs at the recollection, that would be impossible to do today.

And while Guldemond says it was an introduction to Finch and his riding style that showed him what was possible on a snowboard, the real progression—in life lessons from Finch—is what turned him not only into the pro he became, but the person he is now that his snowboarding career is over. He’s living in San Diego, raising a family and working as foreman of a construction crew building custom homes—en route to getting his master builder’s certification.

“I think transitioning from a pro career in any circumstance is hard—the hardest thing I went through,” Guldemond says. “I set guidelines for myself, but when it came time, it’s a really tough spot; it’s where depression and anxiety and gnarly things can come from. But when you look at guys like Andy who did it first, who took that first step, it’s like, ‘OK, I’ve been following in this guy’s footsteps, and now this is how he made the transition—I can too.’”

Humphries agrees. Like Guldemond, he loves watching Finch on the snow—whether it’s clips from his early days or they’re taking a backcountry trip together on sleds—but he says the thing he respects most about Finch is the way he’s guided others with an almost invisible hand, by setting the example.

“He’s probably the most clean-cut person I know,” Humphries says. “There’s literally, I can’t … he’s straight up the most solid dude I’ve met.

“I’ve seen a lot of snowboarders who might have been more successful, but he’s this combination of one who did it so well and was then smart enough to invest. … He didn’t make contest loot and blow it on stupid shit—you do that, you’re going to be broke, which is what I learned from him. Make smarter investments: index funds, real estate—put [your money] in things that will continue to grow.”

‘By Grace, Lots of Grace’

Finch demurs when asked about being a role model to other snowboarders. He notes that the community is tiny in professional snowboarding, and the time to pursue the career is so finite there’s not a ton of room for mentorship among peers.

He does, however, acknowledge that setting an example, without trying to set an example, might be something that comes naturally from factors going back to his upbringing in a musical family (Finch started playing the violin at age 4 and can still bust out most songs from pop to classical by ear), and with a father who showed him the outdoors from an early age.

Andy Finch enjoys deep powder and blue skies in the Tahoe backcountry, photo by Mike Basich

“Fresno’s farmland,” Finch says, laughing. “It’s in the middle of nowhere, but yet it’s in the middle of everywhere. Therefore, it’s ‘FresYes.’”

It was during his formative years that an emphasis on family and faith was instilled in him, and that’s been the plumb line through his career both during and after snowboarding.

“By grace, lots of grace, is why I’m here,” he says. “You know, I think having good mentors, as well … people I looked up to and respected and tried to emulate. But even with that, there’s such a lure to squander, and there’s plenty of opportunity. I believe there’s a protection over me spiritually.”

Finch’s faith is well-documented—but also, unlike his flourishes on the hill, it’s not something he does for show. Several times a season, he leads a church service overlooking Lake Tahoe from Diamond Peak’s Crystal Ridge. “It’s usually four to six people. It’s pretty chill,” he says. “Even on some of the days when it’s stormy, we still meet. It’s still really cool. I really like Diamond Peak—real similar mountain to the one I grew up on.”

Post-snowboarding, Finch gained his biggest celebrity fame as a member of the “pro snowboarder” team Andy Finch and Tommy Czeschin on the Amazing Race season 19, which aired in 2011. Czeschin remains one of his closest friends. “We always enjoy hanging out,” Finch says, “but anyone who has a family knows your friends change so much depending on who your kids hang out with.”

Finch and his wife Amber have two children, a 10-year-old son and 8-year-old daughter, and these days most of their activities revolve around them. Whether it’s soccer or music or even snowboarding, life as a father is “everything,” Finch says.

“It’s all-consuming. When I decided to retire in 2011, a lot of that decision came about because I always had a dream of doing active things with my children. … I wanted to preserve my body enough to play with my children.”

Rediscovering a New Niche

And play (and work) he still does. Finch’s latest pursuit is called Surf ’n Foil Tahoe. Finch is both a boat captain and coach who takes guests out on the water to hone the craft of wake surfing or foil riding.

Being on the water, Finch says, is as important to him as being on the snow. “Still chasing waves and chasing frozen waves in the mountains,” says Finch, who also visits his family’s home in Morro Bay on California’s Central Coast, where he learned to surf growing up.

Klein says Finch’s former sponsor, Rip Curl, a surf company specializing in wetsuits and apparel, was a great fit for a rider whose undeniable style on the slopes was shaped by his gravitation toward water.

Andy Finch with a foil air at Boca Reservoir. Finch, who has a strong background in watersports, launched Surf ’n Foil Tahoe this past summer, teaching wake surfing and foil riding behind a hybrid boat that features a pontoon deck on top and a traditional V-drive mono hull on bottom, photo by Court Leve

“Andy’s style naturally showed he was comfortable [on the water]. That’s where his consistency, power and aggression was born, but he’s so rad,” Klein says.

Focusing on his latest venture has led Finch to do what he does best—rediscover a new niche.

“I specialize in teaching people, for sure,” Finch says, describing the experience from being mic’d up and in the ear of his student to meeting a client’s every need with the latest equipment: boat, boards, wetsuits, even food—but especially with the type of waves he creates. “I make an excellent wave. I refer to myself as a wave geek and know how to dial in the wave just right for people. And with foiling, I’ve developed some cheat codes for progression—found a way to make it attainable and safe.”

Those who get on the water with Finch often don’t know him from his past as a snowboarder or even his stint on TV. Sometimes, someone will vaguely recognize him or recall a contest where they saw him. And that’s always rewarding.

“It’s nice when people remember you,” Finch says. “I’ll see someone down the road who’s excited to run into me. But it’s [in the] past. It’s history. It is what it is. I cherish the memories. It doesn’t last forever. Everything goes away.”

That’s one way to look at it, though others disagree that what Finch does is at all fleeting.

“I remember when I was brought into the circle and a handful of guys gave me respect in the Tahoe area—that’s how I met Andy,” Guldemond says. “He’s really had an impact on my life and my success in the sport and in Tahoe, but also, those are the lessons I take with me today.”

Andrew Pridgen once got to follow Andy Finch through the aspen trees on a sunny powder day in Utah. He was unable to keep up.

Ken

Posted at 17:33h, 06 NovemberSo well worth the time reading,

Inspirational and visually memorable.