02 Jul Behind the Curtain: Robin Williams at Tahoe

The late actor and comedian is remembered fondly at Lake Tahoe, where he vacationed often to escape the pressures of fame

As one of the most iconic actors in the history of motion pictures, Robin Williams is naturally associated with Hollywood. But the peerless comedic actor spent his formative years in Northern California, attending high school in the Bay Area, and visited Lake Tahoe throughout his adult life.

“He came to Lake Tahoe every season,” says renowned Tahoe chef Douglas Dale, who co-founded Wolfdale’s Cuisine Unique in 1976. “He loved winter up here because he skied. He was very athletic and agile, which, of course, meant he enjoyed hiking and biking in the summertime.”

Dale developed a friendship with Williams, who frequented Wolfdale’s during his forays up to the lake.

“One of the things we really specialize in is protecting famous people’s privacy,” Dale says. “But with Robin, you had to read him a little bit, because he was really into a quiet night with his wife or friends, or he would be in the bar just on fire.”

Dale recalls one occasion when Williams invited members of the Monty Python cast, who were staying with him at Alpine Meadows, to dinner at Wolfdale’s. After finishing their meal, they repaired to the bar, where they engaged in a rollicking display of improvisational comedic one-upmanship.

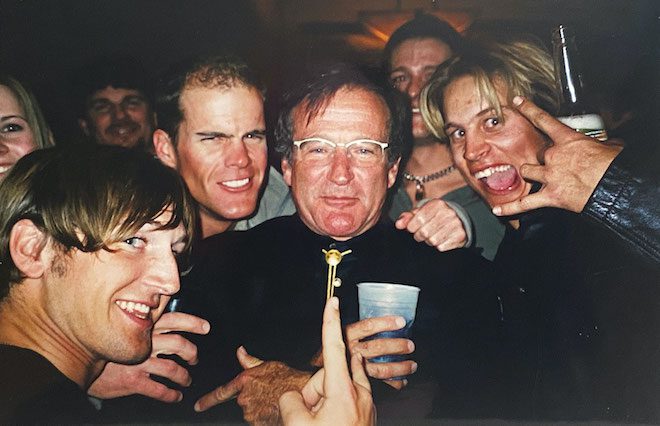

Robin Williams at a celebrity ski event in Olympic Valley in 2003. Pictured with Williams, from left, are Boyd Easley, Scott Gaffney, Shane Anderson (background) and Cody Townsend, photo courtesy Scott Gaffney

“They were all masters of improv, so they were in the bar just trying to see who could outdo the other,” Dale says. “So the restaurant became just a giant improv performance.”

Tahoe-based skier and filmmaker Scott Gaffney remembers running into Williams at a celebrity event in Olympic Valley and making an off-color joke after finding himself standing beside the comedian at the urinal. Williams immediately riffed off Gaffney’s quip, taking the joke in a ribald direction that is, unfortunately, unfit for print (this is a family publication, after all).

For Gaffney, the exchange provided a window into Williams’ prodigious comedic genius.

“It was clear right then and there that that comedic spontaneity is why he was a star,” Gaffney says.

Beyond the sharp wit and humor, Gaffney says he also appreciated Williams’ common touch.

“Later that evening I saw him again and told him how impressed I was that I knew many people who had dealt with him in one way or another up in Tahoe, and everyone just had glowing things to say about him,” Gaffney recalls. “He simply responded, ‘That’s just how you have to be. Everyone matters.’ A few friends and I got a shot with him, and that was that.”

Famously Friendly

It’s a story told again and again by those who lived and worked at Tahoe and were fortunate enough to interact with the international star: Williams was a down-to-earth guy who treated others—ordinary folk included—with kindness and respect.

Greg Felsch was the director of skiing services at Alpine Meadows in the 1990s and interacted often with Williams, as he gave personal ski lessons to his children, Zachary, Zelda and Cody.

“He wasn’t always the outgoing person you see on TV,” Felsch says. “He was just a regular, low-key person when he was by himself or with his family. And he was always gracious.”

Felsch believes Williams liked him to teach his children because he took a subdued approach to the situation out of respect for the family’s privacy.

“He appreciated the fact through the years that when he came up, I didn’t make a big deal out of it,” Felsch says. “We just tried to keep it low key, off to the side … because for him, what I got, it was more important that the kids have a good time.”

Both Dale and Felsch say Williams came to Tahoe for the same reason most people do—to commune with the outdoors and engage athletically in a mountain paradise.

Williams was a proficient telemark skier and devoted cyclist who boasted a collection of more than 80 bicycles. He enjoyed both activities when he visited Tahoe.

“He was a capable athlete, very strong legs, very good balance, and he was comfortable on skis,” says Dale, who accompanied him on the hill several times.

In fact, Dale says he believes Williams’ suicide in 2014 was tied to his physical decline. Williams was diagnosed after his death with Lewy body dementia, which can lead to both cognitive decline and diminished motor skills, similar to Parkinson’s disease.

“I was extremely stunned and sad,” Dale says. “But when I heard of his illness, I understood it, because he was so proud of his athleticism. He did not want to watch his body fall apart.”

These elements of Williams’ personality—his athleticism, his electric, feral verve offset by a contemplative sadness, his generosity—all showed up in his prolific acting career.

While his madcap approach to comedy propelled him to stardom, it was his thoughtful approach to acting that earned him an Oscar and a place in the pantheon of great American actors.

Comedic Genius

Williams was born in Chicago in 1951. His father was a senior executive at Ford Motor Company and his mother was a former model from Jackson, Mississippi. The family moved to the Detroit area when Williams was 12 and then to Tiburon in Marin County after his father took an early retirement.

Williams, who was 16 at the time, attended Redwood High School, where he began taking drama classes and was voted both “Most Unlikely to Succeed” and “Funniest” by his classmates.

He attended community colleges in Orange County and Marin County, where he continued to pursue drama after a brief flirtation with political science. He went on to receive a scholarship to The Juilliard School in New York, one of the world’s most prestigious performing arts schools. He was classmates with William Hurt, Mandy Patinkin and Christopher Reeve, with whom he developed a lifelong friendship.

“He wore tie-dyed shirts with tracksuit bottoms and talked a mile a minute,” Reeve recalled in his autobiography. “I’d never seen so much energy contained in one person. He was like an untied balloon that had been inflated and immediately released. I watched in awe as he virtually caromed off the walls of the classrooms and hallways.”

Instructors at Juilliard, who emphasized classical forms of acting, doubted whether Williams could transcend his wacky antics until he performed in The Night of the Iguana, a play by Tennessee Williams, and awed everyone who attended with his restrained performance.

“I was astonished by his work,” Reeve wrote.

Nevertheless, Juilliard proved too constricting for Williams’ rowdy approach to acting.

“You’re only given one spark of madness,” Williams would later say. “You mustn’t lose it.”

So he dropped out of Juilliard and returned home to the Bay Area, where he bussed tables and bartended at comedy clubs in San Francisco before he finally took the stage as a stand-up comedian.

His stand-up performances are the stuff of legend, completely lunatic, riffing improvisationally on various subjects, an almost stream-of-consciousness display of his hyperkinetic comedic talents.

The performances were so volatile that some critics worried he was on the verge of a meltdown. Williams described his performance style in an interview with Stephen Fry: “Usually, you start off performing in bars, where you can’t really take your time. So, I developed a style that was very much synaptic: quick-firing, moving, so that they never really had a chance to lock on as a target.”

Williams’ inimitable approach cemented his status as a preeminent nightclub comedian.

The opening salvo in his television and film career came in 1978, when he appeared in an episode of Happy Days as an alien named Mork from the planet Ork. His performance proved so popular that it prompted a spin-off, Mork & Mindy, which ran from 1978 through 1982 and launched Williams into another stratum of stardom.

Serious Side

Flush with cash and fame, Williams developed a dangerous addiction to cocaine during this period. He partied with famed comedian John Belushi the night before Belushi died of a drug overdose. He later cited Belushi’s tragic death, along with the birth of his first son, Zachary, as a turning point in his life.

“Was it a wake-up call? Oh yeah, on a huge level,” he told Inside the Actors Sudio in 2001. “The grand jury helped, too.”

To help curb his appetite for illicit drugs, he took to outdoor activities such as skiing and cycling, which he credited for saving his life.

“Reality is just a crutch for people who can’t cope with drugs,” he joked.

Through it all, Williams remained eager to prove he was more than just a comedian.

“I was saying, in effect, ‘I’ll act. I’ll show you I can act,’” he told Rolling Stone in 1988.

In 1987, he paired with Barry Levinson to film what would be his breakthrough cinematic performance, Good Morning, Vietnam. Williams played a rock ‘n’ roll shock jock who kept troops in Vietnam entertained with his comedy. He did impressions of Walter Cronkite, Richard Nixon, Elvis Presley and others, with the filmmakers allowing Williams to improvise nearly all his lines.

“We just let the cameras roll, (and he) managed to create something new for every single take,” producer Mark Johnson was quoted as saying.

Williams earned his first Academy Award nomination for the performance.

He took on other serious roles around this time to burnish his acting credentials, including an appearance with Steve Martin in a stage production of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot.

Even his comedic roles from this era, like Mrs. Doubtfire (1993) and Patch Adams (1998), bore a tinge of seriousness and sadness that displayed Williams’ versatility. However, he perhaps truly came into his own as an actor in Dead Poets Society, released in 1989, in which he played a private-school English teacher attempting to shepherd young men through their formative years. A year later he played a neurologist in Awakenings alongside Robert De Niro in what is arguably one of the most underrated films in his catalog.

All these decidedly dramatic turns culminated in Williams’ performance as a therapist in Good Will Hunting, released in 1997, which earned him his first and only Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor.

Williams had a prolific career, with far too many performances to list here. There is a generation of moviegoers who know him primarily for voicing the Genie in Disney’s animated hit Aladdin (1992). Fans of Christopher Nolan films will highlight his turn in Insomnia (2002), in which he played a serial killer haunting a small town in Alaska alongside Al Pacino, as one of Williams’ best performances. Still others will point to the cult films of surrealist director Terry Gilliam—The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1988) and The Fisher King (1991)—as films where Williams was able to truly unfold the full range of his repertoire.

Gilliam thought so, as the director said in a 1992 interview that Williams could “go from manic to mad to tender and vulnerable,” adding: “He had the most unique mind on the planet. There’s nobody like him out there.”

Lasting Impact

As Williams’ career ascended to a place of rarefied air, earning awards, plaudits and commanding enormous salaries, he often parlayed these benefits into philanthropic causes.

He co-founded Comic Relief USA with Billy Crystal and Whoopi Goldberg in 1986, which went on to raise $50 million for those in need, namely the homeless. He and his second wife Marsha founded the Windfall Foundation, which primarily supports nonprofit organizations, and he spent considerable time entertaining troops with stand-up performances on USO tours around the world.

Williams’ charitable nature also extended to Tahoe. Dale says he would quietly donate to local fundraisers and charities with one strict condition. “His only rule was, ‘I am to remain anonymous. Nobody know where this came from,’” Dale says.

Even after the meteoric success of his film career, Williams never quit stand-up and even performed at Tahoe several times, including as recently as July 2012 when he appeared at what was then MontBleu Resort Casino in Stateline.

Soon after, Williams began to experience the symptoms of Lewy body dementia, which presented as a prolonged spate of fear, anxiety, stress and insomnia, eventually progressing to the point where he experienced delusions and profound paranoia.

Felsch says he was distraught to hear of his death and the health struggles that preceded it—but also that, in a way, he understood. He prefers to remember Williams in his prime, a man of grace and genuine warmth who enjoyed skiing with his family.

“Tahoe was where he came to have family time,” Felsch says.

In hindsight, Dale says he’s glad Williams had Tahoe as a refuge, a place to get away from the pressures of fame and experience the outdoors in all its splendor.

“He considered Tahoe his playground,” Dale says. “He just loved coming to Tahoe. He relaxed here, he played here, he ate here—he did it all.”

Matthew Renda is a former Tahoe resident who now resides in Santa Cruz.

No Comments