10 Aug The Lake of the Sky, Through Many Eyes

Beginning in August, the best view of Lake Tahoe may not be from its sparkling shoreline or one of the Sierra Nevada’s towering peaks, but in downtown Reno’s Nevada Museum of Art (NMA). Here, guests can experience the Tahoe Basin as it has evolved through the centuries in the area’s first comprehensive historical art exhibit. From Washoe basketry to architecture, nineteenth century paintings to contemporary wall installations, Tahoe: A Visual Survey spans more than 200 years and includes works by 175 artists.

A tribute to Incline Village resident and major NMA patron Wayne Prim, the exhibition is comprised of pieces from collections and museums around the country and owes much of its success to sponsors in the community and beyond who are passionate about Lake Tahoe.

The exhibition was almost five years in the making, says museum curator Ann Wolfe. “We worked with a team of scholars who were instrumental to helping identify important works, but to a certain extent this type of survey exhibition is almost like a treasure hunt—one discovery leads to another discovery leads to another, and you find that you have a hard time saying no to people who really want to loan their precious objects so that the public can enjoy them,” she says.

Albert Bierstadt, Donner Lake from the Summit, 1873, Oil on canvas, 72 1/8 x 120 3⁄16 inches, Collection of

The New York Historical Society, New York

Tahoe’s Early Past

Louisa Keyser marketing photograph with LK 44 and LK 59, commissioned by A. Cohn,

circa 1916, Gelatin silver print, 8. x 6. inches, courtesy of Nevada State Museum, Carson City

Tahoe: A Visual History begins with The Lake’s first people, the Washoe, who called it Da’ ow’aga or “edge of the lake.” The Washoe made the annual pilgrimage to The Lake’s shore each spring and stayed through the summer. Woven baskets, made by tribeswomen primarily from willow, were important for carrying food, supplies and children, as well as for aesthetic purposes.

The most famous Washoe basket weaver—and Lake Tahoe’s first great artist—was Louisa Keyser, also known as Dat-So-La-Lee, who lived from about 1829 to 1925. Her baskets sold for thousands of dollars during her lifetime and can fetch hundreds of thousands of dollars today.

“Keyser is known for her innovative development of the degikup basket form that has become synonymous with the fine art of Washoe basketry,” says Wolfe, referencing the tightly coiled, non-utilitarian spherical basket form. “The exhibition will include the largest presentation of baskets by Louisa Keyser ever displayed in one place.”

Louisa Keyser, Seed gathering basket, circa 1910–14, 19 x 19 inches (diam.), Collection of Bronnie and Alan Blaugrund

From Native American artistry, the exhibition charts the progress of American explorers such as John C. Frémont and John Muir as they mapped the land. “The John Muir journal selected is from his 1888 trip to Tahoe and includes some of his quick pencil sketches of his trip around The Lake,” says Wolfe. “The Frémont material consists of maps created by Charles Preuss, who travelled with him on his expedition.”

These feats led to the taming of the land, an enormous achievement as man tunneled through the granite mountains and laid trails and roads over the Sierra spine.

Renowned nineteenth century painter Albert Bierstadt captured one version of these accomplishments in his six-foot-by-ten-foot Donner Lake from the Summit, which was completed in 1873 to wide public acclaim.

“The painting was commissioned by railroad baron Collis P. Huntington, who wanted to celebrate the achievements of the transcontinental railroad,” says Wolfe of the painting, which is on loan from the New York Historical Society. “Also on view will be many of the smaller oil studies that Bierstadt made in preparation for the large painting.”

NMA was careful to not only display the romanticized version of the past in its visual history. For instance, in exploring the region’s railroad history, artwork depicts mighty locomotives and other symbols of man’s conquest over the land, but also explores the lesser-known reality of how the railroads were built, namely, with help from thousands of Chinese laborers, many of whom perished in the construction. In this vein—by contrasting both sides of history—the exhibit strives to start a dialogue: Why were Chinese workers rarely depicted in those early paintings and how are contemporary artists revisiting this history?

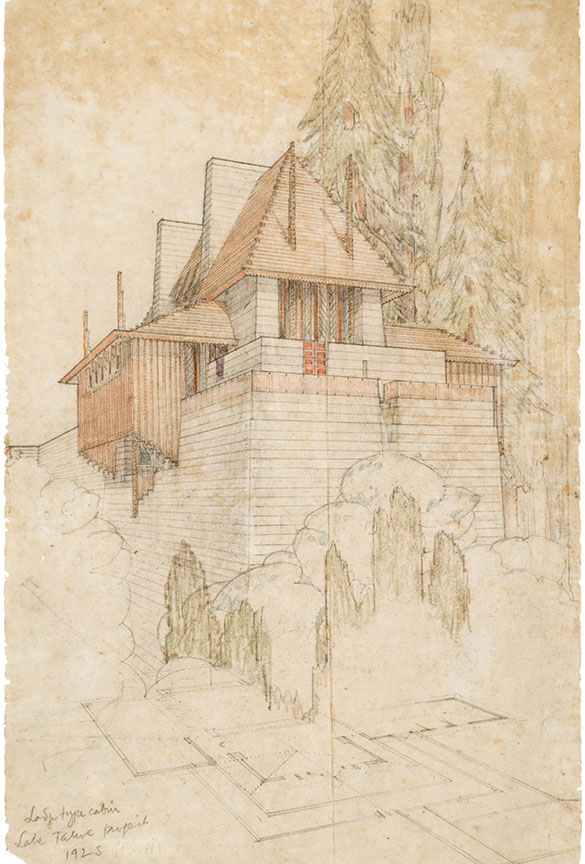

As Lake Tahoe grew popular as a tourist destination, the artwork changed again, with now-vintage posters depicting the area as an elite playground. Resorts and elaborate private residences designed by names such as Frederic de Longchamps and Julia Morgan popped up along the shoreline. One of the NMA’s exhibits—original Frank Lloyd Wright drawings and sketches for a proposed 1923 “Summer Colony” at Emerald Bay—will also explore building that did not occur. “The development plan featured floating cabins and cabins perched along the shoreline,” says Wolfe, adding that a four-foot-by-four-foot model of the proposal will also be on view.

Frank Lloyd Wright, Lodge Type Cabin, Lake Tahoe Summer Colony, California:

Perspective and Plan, 1923, Graphite and colored pencil on Japanese paper,

21 x 13 ¾ inches, Collection Centre Canadien d ’Architecture/Canadian Center for

Architecture, Montreal, Gift of George Jacobsen and of the CCA Founders Circle in

his memory, 1994, © 2014 Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale, Arizona/Artists

Rights Society (ARS), NY

Picture-Perfect

While exploring the different sides of Tahoe’s past, the NMA will also present the most classic of Lake Tahoe views—that is, the pure beauty in the region’s dramatic mountains and crystal-clear alpine waters. That beauty is interpreted in many different forms by many different artists—Ansel Adams’ black-and-white photography, the powerful composition of Maynard Dixon or the magical realism of Phyllis Shafer’s painted landscapes.

“When I was asked to do a piece for the show, I felt like I really wanted to speak for those of us who live at The Lake,” says Shafer. “I felt a responsibility to the fellow denizens of Lake Tahoe.”

Shafer was searching for a place to paint from when a friend took her to the top of Cave Rock. She appreciated the birds-eye perspective, which she “tweaked and torqued” in her signature style, and over several months created About Cave Rock, featuring a native buckwheat wildflower in the foreground blown up 20 to 30 times life-size.

“I’m really anxious to see how The Lake has been interpreted through the ages, and these different voices that are adding to the conversation,” she says. “I’m hoping that my painting adds to that conversation.”

Elizabeth Carmel is a fine arts photographer and co-owner of the Carmel Gallery, with Truckee and Calistoga locations. Two of her works, Sunset, Bonsai Rock and Tahoe Reflections, both shot in November 2006 during a series of moody, foggy sunsets on the East Shore, will be on display.

“I think my work represents a time in our modern era when the art form shifted from film to digital photography,” says Carmel. “I used a state-of-the-art medium format Hasselblad digital camera to capture these images. I was one of the first landscape photographers to use this type of ultra-high resolution camera in 2006. Because of the high resolution, I am able to print the images in the very large format shown in the NMA exhibit.”

In both photographs, the still waters of The Lake reflect the boulders and the scenery. Coupled with the evening fog, the boulders seem to float tranquilly on the surface. “Many people have commented that they have a ‘Zen’ feel to them, very still and meditative,” says Carmel.

When asked what she wants viewers to take away from her work, she refers to her artist statement, which says, in part, “My goal is to contribute uplifting imagery to the world in a time when we are bombarded with so many negative and sensationalistic images. I hope my photographs help nurture a sense of hope and affection for the natural world.”

Exploring a Changing Landscape

Many of today’s artists focus on our unique relationship with this special place.

Maya Lin, the celebrated contemporary artist best known for designing the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington D.C., explores the region’s relationship with water in Pin River—Tahoe Watershed. The NMA commissioned Lin to create a piece in response to Lake Tahoe’s landscape. Lin met with U.C. Davis Tahoe Environmental Research Center scientists to find inspiration for her 25-foot wall installation. Made from thousands of straight pins, the exhibit allows the viewer to contemplate the complex system of water—rivers, lakes, dams, pools, bays and inlets—that make up the Lake Tahoe watershed.

Maya Lin, Pin River—Tahoe Watershed, 2014, Straight pins, 21 x 114 x 1 inches, Collection of Nevada Museum of

Art, Museum purchase with funds provided by Marion Grudin in memory of Shim Grudin, photo by Kerry Ryan

McFate, © Maya Lin Studio, courtesy Pace Gallery

Peter Goin chairs the Department of Art at the University of Nevada, Reno, where he teaches photography. The NMA exhibit includes several works from his book Stopping Time. The series, in which Goin pairs a historic photo with a contemporary photo of the same spot, provides the viewer with an analysis of the evolving landscape. “Viewing fragments of time within history, arrested within the image, engages the viewer in their own analysis and comparison, enabling on some level the educational process,” says Goin. “Learning about place is part of our connection to where we live, and enriches our lives as we understand the forces of climate, growth, adaption and change.”

Another of Goin’s works, Seneca Pond, will be featured, representing South Lake Tahoe’s devastating 2007 Angora Fire by presenting a time-based visual study of the post-fire landscape. He chose ten sites, including Seneca Pond, near where the fire began, and over the course of many months created individual pictures as well as a time-based merging of the collected photographs, allowing the viewer to observe how the landscape changes and regrows in the aftermath of such a destructive forest fire.

“This series invokes a conversation among the arts and sciences; that is, the language of the fine arts,” says Goin. “Photography is employed to articulate and explore the post-fire consequences and evolution of the Tahoe landscape.”

Also exploring the subject of forest fires is Fort Collins, Colorado-based Erika Osborne, whose Back of the Map exhibit was featured at the museum in 2013.

For Tahoe: A Visual History, she created Tahoe Basin Management: What is Lost and What Remains. Osborne spoke with several Nevada forest ecologists before heading to South Lake Tahoe to get some “ground truth” on the area.

“What stood out in all this research was the larger picture of forest health resulting from decades of fire suppression,” Osborne says. “This forest management practice has led to overcrowded forests—in the Tahoe area and around the country—that are more susceptible to catastrophic fires, disease and the larger impacts of climate change. This was made apparent with the Angora Fire of 2007.”

Osborne spent several days creating rubbings of stumps from trees that were killed in the fire. She also hiked Cathedral Peak, near Mt. Tallac, to visit ancient juniper trees she’d learned about in her research. “In contrast to the trees killed in the Angora Fire, these junipers have remained incredibly adaptable to human impact and climate change—standing in the same spots for a millennia,” says Osborne.

Osborne returned to Colorado where she completed a drawing of one of the ancient junipers and cleaned up a rubbing of one of the tree stumps from the Angora Fire. From this, she created a map of the Lake Tahoe region that included all the forest fires recorded in the last 50 years—color coded largest to smallest—noting subsequent fire management projects and the GPS coordinates for both the juniper tree and stump. “I printed this map at about eight feet,” she says. “I then put a model in front of it, painting the lines and overlays of the map his body displaced across his back—fusing him with the topography.”

In contrast to Osborne’s previous works, which only painted topographic lines onto a participant’s body, she chose to paint an aerial relief image of the Tahoe Basin. “Of course, it was much harder to do and have it come out right in a day—the time I had allotted to do the drawing, given that it was done with body paints that can wash off, or sweat away. But, we pulled it off.”

After she had taken the photograph with the participant, she removed the part of the map where his body had been.

“I want people to contemplate the myriad of ways that we come to understand and affect our environments,” she says. “Our relationship to place is inherently complicated. We connect abstractly through academic research and cultural systems like maps, which give us insights into political and social issues that result in human interventions. But, we also connect through the direct experience of putting our feet on the ground and exploring a landscape visually. Both forms of connection have their effect on the ecology of any given environment. I hope Tahoe Basin Management: What is Lost and What Remains pieces together a bit of that complexity—addressing human impact on the environment with overlays of information that ultimately culminate in the viewer understanding that we do, in fact, affect the world around us in dramatic ways.”

That being said, she continues, there is hope with the piece as well, found in the representation of the juniper tree. “If you study the work, you can see that the ancient juniper lives in an area that sits outside of forest management. It continues to grow and thrive as it has done for thousands of years. It becomes a beacon of adaptability in the face of climate change, and a symbol of what is possible if we leave our forests alone.”

In exploring two centuries of artwork—from the intricate baskets of the earliest people to today’s look at water issues or fire management—it truly is a unique relationship that we have with this place. It is a place where past accomplishments are now seen as environmental atrocities. Where a storied past collides with an uncertain future. It is a place that we want to preserve but that we are constantly changing. It is a place where hope can be found in the trees and peace can be found in the water. It is—above all—a place of immense beauty.

Reno-based writer and editor Alison Bender is especially interested in the area’s early history and artifacts.

No Comments