27 Apr Mitigating Dam Dangers

Questions arise about the state of aging dams in the Tahoe area

When roughly 180,000 people were evacuated beneath the potentially failing Oroville Dam emergency spillway in Northern California on February 12, it brought into sharp focus what experts have been warning for years: Many of the nation’s dams are in disrepair, posing risks to downstream residents.

The Association of State Dam Safety Officials lists nearly 2,000 hazard-level state-regulated dams across the country, estimating billions of dollars in repairs needed.

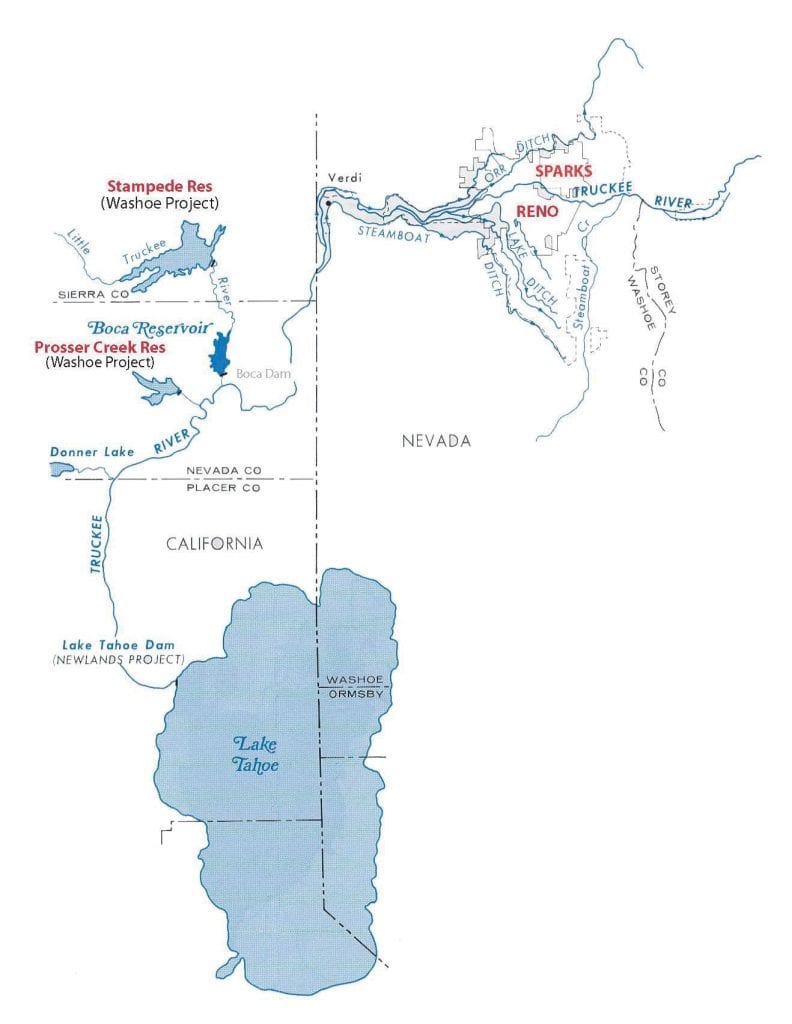

In the Tahoe region, Martis Creek Dam near Truckee ranked as the sixth most dangerous dam in the United States Army Corps of Engineers’ national inventory less than a decade ago. Meanwhile, the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Reclamation found the risks of the dam at Stampede Reservoir, just north of Martis Creek Lake, were three times the acceptable level for safety, known as Public Protection Guidelines. Just downstream of Stampede, Boca Reservoir’s dam exceeds those guidelines by a factor of 25.

Each of those dams feeds into the Truckee River and toward the 420,000 residents who live in the Reno–Sparks area below—one of the main factors in assessing their risk.

But since each dam’s unique risks have been assessed, steps have already been taken to ensure their safety, and the safety of those downstream. None pose the level of threat of Oroville, though officials working on them are feeling the pressure of that near miss.

“When we had to evacuate nearly 200,000 people it certainly raised awareness of dam safety,” says Todd Hill, project manager with the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s Dams Safety Program. “We’ve been answering quite a bit of questions from the public and from Congress, and everyone in between.”

Martis Creek Dam

The 113-foot-tall earth-fill Martis Creek Dam was completed in 1972. The dam is able to hold back 20,391 acre-feet of Martis Creek on its way across the Martis Valley, near Truckee Tahoe Airport, before it feeds into the Truckee River east of the Highway 267 bypass.

“When they built the dam, they couldn’t dig deep enough to build on bedrock, which is where we like to build most dams,” says Doug Gothe, park manager for Martis Creek and other reservoirs in the region for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. “They decided to put additional impervious materials in the dam to keep it from seeping and it pretty much worked—except when they did test fills.”

The last test fill, conducted in 1995, brought other issues to light. Water started seeping out places not expected, Gothe says. The water was the highest it had ever been—an elevation of 5,833 feet (the gross pool tops out at 5,838 feet).

Martis Creek Lake is shown before it was lowered indefinitely to minimum pool, photo by Michael J. Nevins

Martis Creek Lake is shown before it was lowered indefinitely to minimum pool, photo by Michael J. Nevins

In spite of efforts to put impervious surfaces on the lake bed upstream from the dam and other work, the Army Corps declared the dam a Class One, Gothe says, the most dangerous rating on a scale of one to five.

Coarse glacial soil under the reservoir foiled efforts to prevent seepage that could—in a worst-case scenario—destabilize the dam, so officials dropped the water level of Martis Creek Lake to minimum pool, retaining only 800 acre-feet of water.

In the 2000s, engineers began an evaluation and study of Martis Creek Dam, drilling numerous 4- to 8-inch-diameter wells on the upstream side of the dam looking for bedrock, assessing the geology and trying to get a better picture of what was happening underground, Gothe says.

In 2009, the Polaris Fault was discovered near the dam, compounding safety concerns. But the Army Corps’ decision to keep the reservoir at minimum pool mitigates the risk from that fault as well, Gothe says.

From 2013 to 2016, an Army Corps team set out to evaluate that study—to examine possible solutions from shoring up the dam to taking it out altogether—and reevaluated figures used in the ’70s to build the dam with modern technology and information.

“After getting all this data, last summer they made the determination that with the measures we’re taking right now, Martis Creek Dam is no longer a Level One,” Gothe says. “They reduced the risk calculation to a three, which is basically safe.”

Those measures include keeping the dam gates open to keep the reservoir at minimum pool, not to go above 5,810 feet in elevation (8,000 acre-feet of water), he says, along with extensive monitoring and other minor modifications to the dam.

“If the lake starts creeping up to 5,810 feet, they send in the engineers, but we’ve never reached that level since we’ve stopped doing test fills,” Gothe says. “The gates are always open. If the dam failed with that much water, you probably wouldn’t even notice it by the time it got to the Truckee River.”

Looking to the spring runoff after the massive snowfall of this winter, Gothe says the Army Corps isn’t anticipating any problems with Martis Creek Dam.

Boca and Stampede

On the north side of the Truckee River, Boca and Stampede reservoirs help regulate flow and store water from the Little Truckee River into the Truckee. Stampede, with its 239-foot-tall earth-fill dam completed in 1970, feeds into Boca, which is held back by a 116-foot-tall earth-fill dam completed in 1939.

The risk for Stampede, considered three times higher than the acceptable levels of the Public Protection Guidelines of the Bureau of Reclamation, comes from the potential of an extreme flood event overtopping the dam, which would cause Boca Reservoir downstream to fail, Hill says. The fix is to raise the dam by 11.5 feet.

“We’re already in construction and will be working through 2018,” Hill says. “We’re putting in two vertical concrete walls on either side of the crest of the dam, with compacted earth in between.”

Additionally, two small dykes elsewhere on the reservoir block low spots—or saddles—that would overtop at that new level, he says.

While that extreme flood event is highly unlikely, the large downstream population makes it unacceptable, Hill says. The dam itself is in good standing structurally, and poses no other risks.

Work is also planned for Boca Dam, which is potentially susceptible to an earthquake, Hill says.

“When the dam was built in the ’30s, they left some alluvium that is potentially liquefiable in an earthquake, which could cause the dam to overtop or crack and deform,” Hill says.

Boca Dam, photo by Sylas Wright

Boca Dam, photo by Sylas Wright

Alluvium—soft silt or sand deposited by water (in this case the Little Truckee River)—can become unstable, or liquefy, in an earthquake, similar to the landfill material that caused many of the problems in San Francisco’s 1906 earthquake.

Working on the downstream side, the Bureau of Reclamation plans to build what is called a shear key and stability berm—replacing the alluvium with compacted earth 15 to 20 feet down, while also buttressing the dam with 150,000 cubic yards of material, Hill says.

“We’re finalizing project design now, and hope to start construction in 2018,” Hill says.

The Dog Valley Fault is within a few miles of the dam, posing the seismic risk to the reservoir.

As for this year’s big snowpack, Hill says there aren’t safety concerns, only figuring out how it will affect the timing of work on the ground this summer.

“We’re looking at weekly hydrologic predictions—figuring out where and when the water might come, trying to get an idea for managing the reservoir in a way that allows us to get in and do the things we need to do,” Hill says.

Regulating the Flow

Along with the structure itself, a lot of dam safety depends on flow regulation, and that’s where the Federal Water Master’s Office in Reno steps in, balancing the numerous reservoirs’ storage and flow.

“We try to operate in the best manner to put as little stress on the system as possible,” says Federal Water Master Chad Blanchard. “With regards to Oroville, it’s something we think about. We feel for the people who have had to deal with it, both the people downstream and who had to make the operational decisions.”

In a big water year such as this, the balancing act is passing water so reservoirs don’t get full too early, before peak inflow from snowmelt, which is typically in late May, Blanchard says. But if they hold back too little and peak flow doesn’t match forecasts, they won’t get the storage they want for the rest of the year supplying the Reno–Sparks area.

“It’s not a perfect science,” Blanchard says. “We have to try and balance down the middle.”

Map courtesy U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Environmental Aspects

While numerous news sources noted that environmental groups like the South Yuba Citizens League voiced concerns over Oroville Dam’s safety years before this winter’s incident, the Truckee River Watershed Council expressed no similar concerns over area dams—focusing their work on environmental impacts instead.

“We haven’t really engaged in the whole dam removal argument that’s been going on in other places,” says Beth Christman, director of restoration programs for the watershed council. “These are established dams in our watershed that aren’t going anywhere, so our energy is better suited somewhere else.”

The council instead is focused on how flow is controlled from dams and the effects of those flows on the downstream ecology, she says, along with restoration work for fish-spawning habitat below dams.

“We’ve been really engaged in how reservoir operations affect in-stream habitat,” Christman says.

With the Truckee River Operations Agreement in place for the first time in 2016, watershed council staff have been working with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and the California Department of Water Resources to make recommendations for preferred flows for fish—maximum flows, minimum flows and how quickly those flows are ramped up or down.

Placing gravel and other materials needed for spawning habitats downstream of dams has been a part of their work as well, as dams prevent those materials from being naturally deposited from upstream, Christman says.

So while dams in the Truckee–Tahoe area are aging, local authorities are taking every step to make sure they are safe, ensuring residents won’t need to worry about a disaster on par with Oroville’s close call.

Greyson Howard is a Truckee-based writer. Learn more at www.greysonhowardmedia.com.

What about Tahoe?

The Lake Tahoe Dam, which releases water into the Truckee River, is a different animal than Martis Creek, Stampede or Boca. Built in 1913—and modified in 1987 under the Safety of Dams program—Tahoe’s dam is only 18.2 feet tall and 109 feet long, which is diminutive compared to other dams in the area, especially when considering Tahoe’s 1,644-foot depth. The difference is that Tahoe is a natural lake, and only the top 6.1 feet of water is controlled by the dam. Even so, because of Tahoe’s large surface area, the dam stores 732,000 acre-feet of water when The Lake is full. Compare that to Stampede, which takes a 239-foot-tall, 1,511-foot-long dam to store 226,500 acre-feet when full.

No Comments