29 Sep Cloud-Seeding Drones on Hold

Desert Research Institute eyeing 2018–19 winter for project

Ambitious plans to boost snowfall in the Lake Tahoe region via drones came to a halt last winter, with huge storms reducing the need for man-made snow and regulatory processes hampering researchers’ hopes of flying their unmanned aircraft through winter storm clouds.

Now, scientists at Reno’s Desert Research Institute (DRI) say it will likely be at least a year before they can send drones into the teeth of winter storms to produce additional precipitation through a process called cloud seeding. To date, drones have never been used for such a purpose.

Congressional Hold-ups

In 2013, Nevada was given a special designation as a UAS (unmanned aircraft systems) test site by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). This designation allows scientists to use unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), more commonly known as drones, for a variety of potential applications. DRI researchers had hoped to work with the FAA to gain approval for in-cloud testing of UAVs above the Tahoe Basin during the 2016–17 winter.

“We were hoping to leverage our technical progress into regulatory progress, but that didn’t happen,” says Frank McDonough, a cloud physicist and manager of DRI’s weather modification program. “It is frustrating, but for us it’s more about costs. We looked at it and decided it was cost prohibitive at this point to pursue the FAA’s extensive and exhaustive permitting process.”

Congress is currently reviewing the Federal Aviation Administration Reauthorization Act of 2017 that would, among other things, provide an extension of the current UAS test site programs, allowing UAS test sites such as Nevada to continue research and development. The bill specifically directs the FAA administrator to streamline the approval process for test sites and encourage flights of unmanned aircraft equipped with sense-and-avoid and “beyond-visual-line-of-sight” (BVLOS) systems at the test sites for continued research, development, testing and evaluation toward the safe integration of unmanned aircraft into the national airspace system.

McDonough and his colleagues are not counting on the bill’s reauthorization in time for the 2017–18 winter. They’re looking to the following year as likely the soonest opportunity to test drones for cloud-seeding purposes.

“There will be no flights over Tahoe this coming winter,” McDonough says.

UAS pilots from Drone America prepare the Savant Unmanned Cloud-Seeding aircraft for flight at Hawthorne Industrial Airport, photo courtesy Drone America

Storm Assists

For more than 30 years, DRI scientists have worked to coax additional snow out of storm clouds, primarily through the use of five ground-based generators installed on mountaintops along the Sierra Crest west of Tahoe.

When winter storms approach and temperatures and other atmospheric conditions align properly, the mountain generators are fired up. The remotely controlled machines discharge a stream of silver iodide particles, a substance with a molecular makeup closely matching that of ice crystals.

The particles adhere to tiny ice crystals present in storm clouds, causing them to grow in size and fall to the ground as snowflakes. Without the human-induced changes brought by seeding, that moisture would likely pass the Tahoe area and evaporate.

On average, snowfall generated by DRI’s cloud-seeding operation is estimated to provide an additional 14,000 acre-feet of water, or 4.5 billion gallons, to the watersheds of Lake Tahoe and the Truckee River each winter. In an effort to help the area recover from a four-year drought, the generators were used 38 times during the 2015–16 winter, producing an estimated 19,021 acre-feet of extra water, or 6.1 billion gallons, McDonough says.

One of DRI’s five active ground-based cloud-seeding generators sits near the summit of Ward Peak on Lake Tahoe’s North Shore, photo courtesy DRI

Limited Need to Seed

Cloud-seeding operations were far more limited last winter due to the season’s epic intensity. A series of powerful storms, referred to as “atmospheric river” events, hammered the Sierra, particularly in January and February.

According to the National Weather Service, the Northern Sierra experienced the wettest year on record dating back to 1922. Some 89.7 inches of rain or melted snow soaked the region between October 1 and mid-April, producing nearly 7.5 feet of water and surpassing the previous winter record set in 1982–83.

All that natural snow meant curtailing cloud-seeding operations. DRI’s protocol calls for operations to halt if there’s any chance seeding could possibly contribute to flooding or other problems.

Last winter, cloud-seeding generators were activated only nine times between November and early January, producing an estimated 6,000 acre-feet of water.

“After that, we saw that first massive atmospheric river lining up and we just shut it down,” McDonough says.

DRI’s ground-based cloud seeding operations in the Tahoe Basin—funded by Nevada water providers—are expected to continue during the coming winter but on a much more limited scale than usual. The reason? The prodigious winter has Lake Tahoe and the region’s other major reservoirs still brimming with water.

“There’s not a giant need for water this coming year,” McDonough says. “All the reservoirs are in real good shape. It was an incredible rebound we had.”

The rebound occurred after a historic drought that withered the Sierra between 2012 and 2015, drastically lowering Lake Tahoe’s water levels and nearly drying up the Truckee River in some locations. During such dry periods, cloud seeding can make a real difference in supplying extra water, and that’s why McDonough and colleagues say the program remains important.

The Savant Unmanned Cloud-Seeding aircraft successfully deploys wing-mounted cloud-seeding flares during a test flight near Hawthorne Industrial Airport in Nevada, photo courtesy Drone America

The Savant Unmanned Cloud-Seeding aircraft successfully deploys wing-mounted cloud-seeding flares during a test flight near Hawthorne Industrial Airport in Nevada, photo courtesy Drone America

Future Seeding

Drones are expected to enhance cloud-seeding operations. The UAVs could effectively target specific parts of a storm deemed to have the most potential to generate snowfall, something not possible with ground-based generators. Drones can be used at lower altitudes and at less cost and risk than manned aircraft.

Efforts ramped up last year when DRI, Reno-based Drone America and the Las Vegas–based aerospace firm AviSight announced a collaborative effort to aggressively explore the potential application of drones in cloud seeding. The program is funded by the Nevada Governor’s Office of Economic Development, which has made the development and testing of drone technology a top priority for the state.

And while his team didn’t obtain federal permission for actual in-cloud testing of drones last winter, significant progress was made in other areas, McDonough says.

Perhaps the most important milestone occurred in mid-February when researchers successfully completed a BVLOS test of a fixed-wing Savant drone near Hawthorne, Nevada. The remotely operated vehicle traveled some 30 miles and reached an altitude of 1,200 feet during a nearly hour-long flight.

“Today we demonstrated without a doubt that our unmanned cloud-seeding technology and capabilities can move beyond line of sight, a significant hurdle in this industry,” Adam Watts, DRI’s principal investigator for the project, said in a statement issued shortly after the test.

“We checked that box off,” McDonough agrees. “Obviously, when you are cloud seeding you have to fly the UAV to a place where you can’t see it, a place far beyond the pilot’s visual line of sight.”

Also tested successfully were silver iodide flares, both those that disburse the chemical directly from drones and others that could be ejected from the aircraft into storm clouds.

Other efforts have focused on potential problems created by ice forming on the drones while they fly through a storm. The same subfreezing water droplets that are the target of seeding operations could accumulate on the aircraft, posing a significant danger of forcing it to the ground. Researchers are looking at installing heating instruments or other technology to address this issue.

“Icing is probably one of the biggest challenges,” McDonough says. “That’s the kind of stuff the UAV will have to fly into and that’s still a hurdle that has to be passed.”

But researchers say they remain committed to overcoming the challenge and others when it comes to drones and their potential role in squeezing every possible snowflake out of Sierra storms.

“We will continue to push the envelope,” McDonough says.

Jeff DeLong is a freelance writer based in Incline Village. Special thanks to Justin Broglio at Desert Research Institute for his assistance.

Photo courtesy DRI

Stories in the Snow

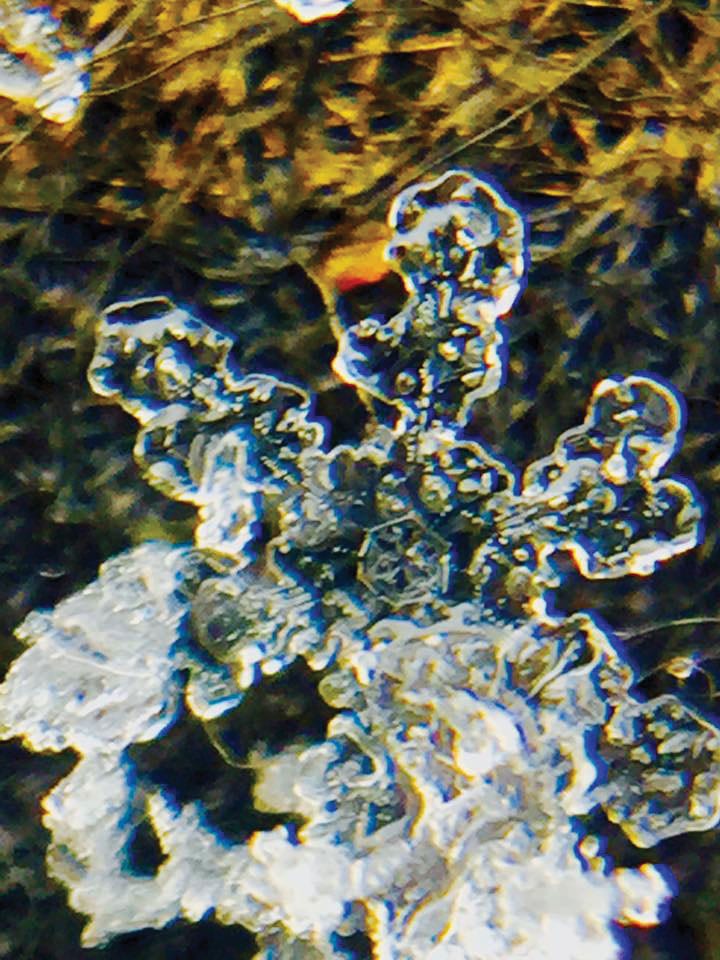

It’s said that no two snowflakes are the same, which is why scientists are reaching out to residents and students across Tahoe and Northern Nevada in an effort to determine the scientific tale told by each flake.

“Every snowflake has a story,” says Meghan Collins, an assistant research scientist in STEM education at Reno’s Desert Research Institute (DRI).

As part of DRI’s new “Stories in the Snow” citizen science program, scientists are asking folks across the region to use their smartphones—fitted with a special macro lens—to photograph snowflakes during the coming winter. Scientists can study images of the freshly fallen crystals to determine atmospheric conditions that existed during a given snowstorm.

Following a successful pilot program conducted at four area schools last winter, this will be the first full season for the “Stories in the Snow” project, Collins says.

The idea is to allow students and others to help track the path a snowflake has taken through the atmosphere. Photographic images of snowflakes taken by citizen scientists will be matched with information such as temperature, wind speed and direction, visibility and radar data.

The first-of-its-kind project may produce valuable information to help validate weather models, associate ice crystal structure with avalanche frequency and help to determine effectiveness of cloud-seeding operations, scientists say.

“Our intention is to really take a creative and a very hands-on approach to science,” Collins says. “We are really, really excited about this.”

Photo courtesy DRI

How to participate

• Visit www.storiesinthesnow.org and click “Get your kit.”

• On your smartphone, search “Citizen Science Lake Tahoe” wherever you get your apps. Install the free app and join the community.

• Watch the how-to video on the website and learn how to collect snow crystal images.

• Take a picture with your phone and macro lens and upload it to the app.

• Like “Stories in the Snow” on Facebook and follow @StoriesintheSnow on Instagram.

No Comments