01 Oct Clarity Loss Overshadowed by Climate Change

Tahoe’s clarity culprit is the historic winter of 2016–17, but climate change raises troubling, long-term concerns for the lake

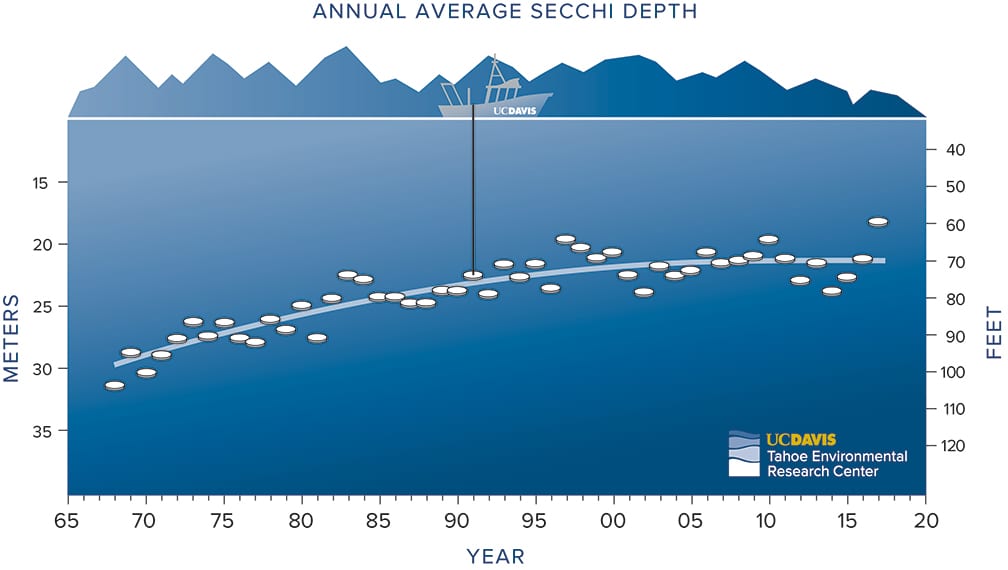

Last year was the worst year for Lake Tahoe’s clarity since anyone started paying attention.

That said, it was a fluke. The bigger problem—and it may be bigger than anyone can know—lies ahead as the climate continues to warm, raising water temperatures and producing potentially widespread changes for a sensitive ecosystem.

“It could change everything,” says Geoffrey Schladow, director of the UC Davis Tahoe Environmental Research Center.

In 2017, Lake Tahoe’s average clarity was 59.7 feet, the lowest since measurements began 50 years ago. That measurement represents a 9.5-foot decrease from 2016 and surpassed the previous lowest clarity of 64.1 feet recorded in 1997, when winter floodwaters washed massive amounts of sediment into the lake.

2017 Secchi data, Annual Average Secchi Depth, courtesy UC Davis

2017 Secchi data, Annual Average Secchi Depth, courtesy UC Davis

A similar situation occurred during the winter of 2016–17, which produced the wettest water year in the Sierra dating back to 1922. Nearly 7.5 feet of water—rain and melted snow—fell between October 1 and mid-April, surpassing the previous record set during the winter of 1982–83, according to the National Weather Service.

That epic winter followed five years of drought, which left sediment that normally would have washed into the lake trapped on land. Heavy runoff during and after the winter flushed all that stuff into the lake at once—more than what washed into its waters during the previous five years combined, according to UC Davis’ 2018 “State of the Lake” report.

Complicating the matter were unusually warm water temperatures in late summer and fall. Those temperatures may have trapped sediment—which would normally plunge deep that time of year—near the lake’s surface, further reducing clarity.

Combined, these factors made 2017 something of an anomaly when it comes to lake clarity, Schladow says. Readings for the first seven months of 2018 showed clarity at about 73 feet, indicating an overall trend of improving clarity is still on track.

“I think that’s encouraging,” says Schladow. “Last year didn’t indicate that what we’ve been doing all these years is ineffective. That isn’t true at all.”

Brant Allen, field lab director and boat captain for the UC Davis Tahoe Environmental Research Center, uses a white Secchi disk to measure water clarity in Lake Tahoe, photo courtesy UC Davis

Brant Allen, field lab director and boat captain for the UC Davis Tahoe Environmental Research Center, uses a white Secchi disk to measure water clarity in Lake Tahoe, photo courtesy UC Davis

Clear Progress

Since 1968, when Tahoe’s clarity reached more than 100 feet, scientists have carefully monitored changes in the transparency of its famously clear waters. They do so through the use of a Secchi disk, a white, dinner plate–like device that is lowered from a research boat into the depths until it disappears from view.

For many years, the news wasn’t good. Researchers measured a steady loss in lake clarity, a trend associated with human-induced changes that promoted algae growth and flushed fine sediment into the lake from roadways, urban centers and streams.

Much work and many millions of dollars have gone into reversing the trend of clarity loss. Roadways and parking lots were retrofitted to prevent the flushing of sediment into the lake. Wetlands and streams were restored to act as natural filters.

Since 1997, when then-President Bill Clinton convened the first Lake Tahoe Summit to address Tahoe’s many environmental ills, more than $2 billion in federal, state, local government and private funds have been spent, with reversing clarity loss the central goal. Completed projects keep an estimated 300,000 pounds of fine sediment per year from entering the lake.

The work appears to have paid off. Since around 2000, the troubling trend has slowed or stabilized, with scientists expressing optimism that Tahoe’s clarity could one day return to historic levels of near 100 feet.

It’s the long-term and now improving trend that’s important, says Tom Lotshaw, spokesman for the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency. TRPA was established by Congress in 1969 and charged with the task of protecting Tahoe’s environment.

“The steady declines have stabilized,” Lotshaw says. “We know the clarity readings can fluctuate from season to season, from year to year. I think at the end of the day, we’re looking at that trend.”

Research vessel John LaConte on Lake Tahoe, photo courtesy UC Davis

Research vessel John LaConte on Lake Tahoe, photo courtesy UC Davis

Warming as Warning

If 2017 was an outlier, more such events can be anticipated in the future—particularly due to impacts of a warming climate, says Schladow.

“Extreme droughts and more of them are one result of climate change. Extreme winters are another,” he says. “We’re going to have more of these anomalies in the coming decades, I think.”

Looking at the big picture, climate change could pose the single biggest threat to Lake Tahoe and the famed clarity of its waters, Schladow adds.

“Up here climate change isn’t a theory,” he says. “The climate has changed. The lake is getting warmer.”

That was demonstrated in 2017, when Tahoe’s temperature was the warmest on record. Average surface water temperature in July was 68.4 degrees, 6.1 degrees warmer than July 2016 and the highest ever measured.

The trend appeared to be continuing during the hot summer of 2018. During the first week of August, water temperatures at Sand Harbor State Park at a depth of 6 feet were measured at 74.5 degrees, Schladow says.

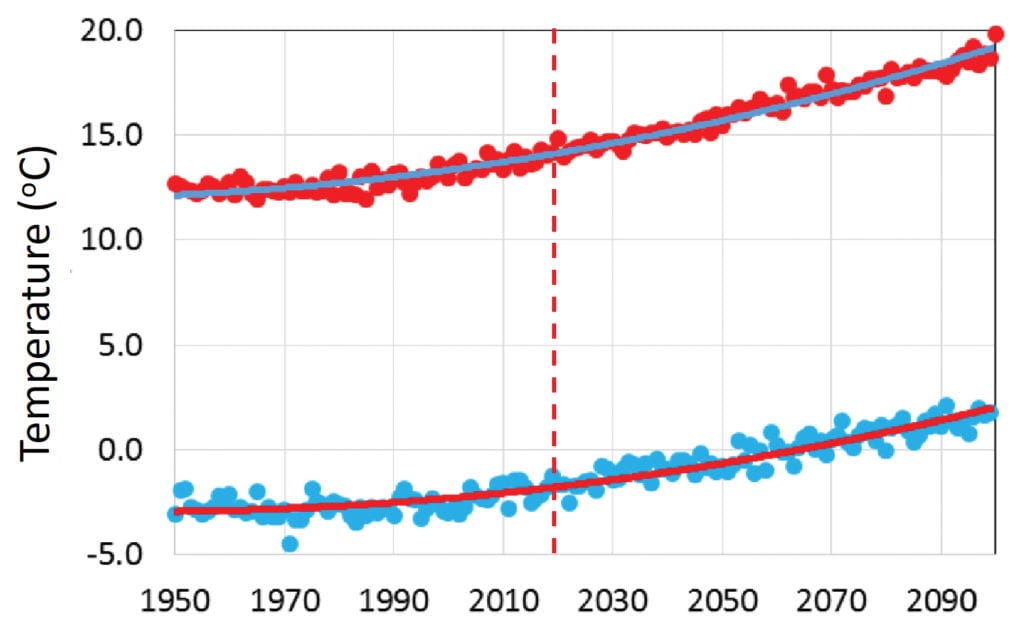

Climate change is evident in this model of maximum and minimum temperature trends averaged over the Tahoe Basin, courtesy UC Davis

Climate change is evident in this model of maximum and minimum temperature trends averaged over the Tahoe Basin, courtesy UC Davis

That’s only about 4 degrees cooler than shallow-water ocean temperatures recorded at the same time by scientists in San Diego.

“We’re at 6,000 feet and we’re just behind San Diego,” Schladow says.

Air temperatures are also expected to increase during the years to come. According to climate models prepared by scientists at the Tahoe Environmental Research Center, temperatures could rise by 7 to 9 degrees between now and the end of the century, likely resulting in significantly less snowfall.

Potential impacts to Tahoe from a warming climate are many and varied. One is the continuing spread of non-native warm-water fish, such as largemouth bass, and the continuing loss of the lake’s minnows and other native species.

A more dire and fundamental risk, Schladow says, could be drastic changes in the lake’s overall chemistry with possible irreversible consequences to clarity.

Normally, the waters of Lake Tahoe “mix” every few years, with warm surface water mixing with the cold, dense water found near the bottom. But climate change is creating longer periods of summer-like conditions and shorter winters, interfering with normal mixing and causing more lengthy periods of stratification of the lake’s water layers. Lake Tahoe hasn’t mixed completely since 2011, and it isn’t certain if it happened for long enough then.

Successful mixing is required for oxygen to reach the lake’s bottom. If oxygen can’t get there, organisms that need it to survive will die.

More dangerous is the potential change in chemistry of bottom sediments, including the possible release of huge amounts of nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorous into Tahoe’s water column, causing unprecedented algae blooms. Tahoe’s famous blue waters could then go green.

“It’s like this whole new source is suddenly unlocked,” Schladow says. “Suddenly we could get a huge influx of nutrients, which could potentially be a tipping point.”

The primary focus in protecting water clarity over the last 20 years has been reducing inflow of fine sediment particles. While that always was and will continue to be important, more attention may need to be directed at reducing input of algae nutrients, Schladow says.

“Maybe we need to give equal value to projects that only reduce nutrients,” he says. “With climate change, there are other things happening in the lake now.”

Jeff DeLong is a freelance writer based in Incline Village.

No Comments