24 Feb A Blast from the Brass Era Past

In the age of technologically advanced contraptions, a longtime Tahoe resident drives against the grain in his 1909 Chalmers-Detroit

Most people these days are eager to have the most cutting-edge technology. Whether it’s the newest iPhone, most waterproof ski jacket or features that nearly drive our cars for us, we revel in the latest and greatest gear.

Doug McNair is not one of these people.

The 63-year-old North Lake Tahoe local pushes against this trend every time he gets behind the wheel of his 1909 Chalmers-Detroit, which has been in his family for 80 of its 110 years. Remarkably, the 4-cylinder, 30-horsepower Brass Era vehicle still runs well and provides a comfortable, relaxing ride—as long as its driver is not in a hurry to get anywhere.

“I run about 35 miles per hour max. You risk breaking something if you go over that,” says McNair, who fittingly rolled up to the 100-year celebration of the Tahoe City Golf Course in his Chalmers-Detroit last year.

Family Gems

McNair’s twin brother Malcolm, who lives in Vermont, is also a car aficionado, owning a 1909 Cadillac along with a handful of classic British cars. The brothers have their father to thank for their relic automobiles.

Doug McNair fuels his 1909 Chalmers-Detroit in Sierraville north of Tahoe, courtesy photo

In the late 1930s, World War II was brewing in Europe and Americans helped by sending scrap medal to England. McNair’s father Robert contributed by locating some of that metal in the form of old cars rusting away in barns in his native New England.

“Back then if something broke they would just put it in the barn,” McNair says. “It didn’t work and they didn’t know how to fix it.”

While the rustiest cars were used for scrap, Robert McNair also picked up a few gems for himself that were still in good shape. They included the 1909 Chalmers-Detroit and 1909 Cadillac. He paid $25 for each. Robert McNair acquired a total of five old cars before his father put a stop to the growing collection, which was filling up his barn.

As a child growing up in New Hampshire, McNair didn’t give much thought to the old cars languishing in his grandfather’s barn. But in 1970, at age 15, his father gifted him the Chalmers-Detroit and gave his brother the Cadillac.

“Dad was an engineer and wanted us to have an interest in cars,” McNair says. “It sat there in the barn for a long, long time after that. In the summer we would go up to see the grandparents, start it and run it a bit, and then put it back away. It never drove on the road.”

After moving to Tahoe in 1979, the car dropped off McNair’s radar.

Primitive Elegance

A product of the Brass Era—cars built between roughly 1890 and 1915—the Chalmers-Detroit was purchased new by a family in New York City for the exorbitant price of $1,250. By comparison, a Ford Model T carried a $600 price tag.

Back then, “people didn’t know how to drive it,” McNair says, “so they hired a chauffeur and he took good care of it, and that is probably why it’s in such good shape.” The chauffeur eventually bought the car from the original owners, and it went through two more owners before it arrived at the McNairs’ barn.

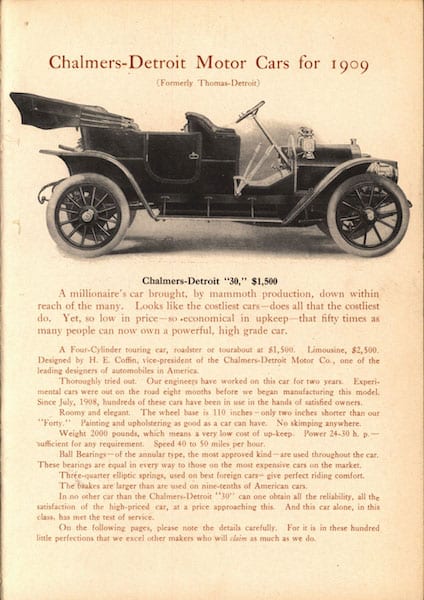

A page from a 1909 Chalmers-Detroit sales manual

Despite the high price, the car did not come with a windshield, top or lights. Those were all extra.

The windshield on McNair’s Chalmers features a horizontal hinge and can be folded in half or removed. The brass headlights are powered by acetylene gas, which, like a stove, require a match to start. Once lit, “it’s like driving down the road with a flashlight,” says McNair, noting that the lights are more for show than night vision. The car also includes two kerosene-running lanterns near the windshield, while McNair added side-view mirrors.

Like the old horse-drawn wagons these vehicles replaced, the large wheels are made of wood, but fortunately have rubber tires to provide a smooth ride and easy steering.

The driver sits on the right, but he or she must enter on the left because emergency brakes block the right side. The interior boasts upholstered seating for five that is plush and comfortable.

Driving the Chalmers-Detroit is tricky business, starting with the hand-crank start. After setting two levers on the steering column in the right position, its operator must put the car in neutral and set the hand brake, then turn the crank with finesse.

“The danger in cranking a car is that if you get the timing wrong, the car could backfire and you are in danger of breaking your wrist,” says McNair. “Many people did break their wrists.”

The Chalmers’ brakes are also not very powerful, because it was assumed the car wouldn’t be going very fast. McNair says he tries to avoid steep downhills and often finds himself having to use the hand brake as well as the foot brake to slow the car to a stop.

On the Road Again

While McNair can be spotted on occasion tootling around the Tahoe region in his Chalmers-Detroit, the car remained quietly stored in the family barn until 2012, when he took it on its first tour with a group in New Hampshire. “It took me three days to get it ready for a one-day tour,” McNair says.

Although the car sold for the exorbitant price of $1,500 in 1909, it did not include a windshield, top or lights, which were all additions, courtesy photo

The bug had finally bit, as McNair then attended the weeklong Brass and Gas Tour in Vermont, followed by the Glidden Tour, a large event with over 300 cars touring the White Mountains of New Hampshire. The car ran well, which is good because replacement parts for Brass Era vehicles—and mechanics with the knowledge to work on them—are not readily available.

For this reason most owners, including McNair, are mechanical-minded problem-solvers who conduct constant research to maintain their vehicles. Reference libraries, such as Reno’s National Automobile Museum, aid their efforts, as well as a giant swap meet in Hershey, Pennsylvania, “where vendors have all sorts of rusty stuff that looks like crap, but is gold if it’s the part you are looking for,” says McNair. The Internet also is a boon for old car owners, who post problems online knowing that somebody out there will likely have a solution.

In 2017 the stars finally aligned for McNair to bring his Chalmers-Detroit to the West Coast: The Glidden Tour was set to take place in Yosemite, and McNair’s daughter Heather was getting married in Tahoe that year. So McNair bought a trailer and convinced his brother Malcom, who was driving to Tahoe anyway for the wedding, to tow the Chalmers-Detroit across the country.

Malcolm caught the old car bug sooner than his brother. He worked with his father in the 1980s to restore his 1909 Cadillac. In 2009 he and his wife Dana commemorated both the 100-year anniversary of the car and the 100-year anniversary of Alice Ramsey becoming the first woman to drive across the country by driving the Caddy coast to coast, from Poughkeepsie, New York, to San Francisco.

“I’d driven the car five times before this, my wife twice,” says Malcolm. The journey took them 60 days, with Dana driving the whole way. Malcolm drove a sag wagon behind. “We had a couple breakdowns, but nothing major,” he says. “Every day we had to clean the carburetor. Every time you stopped for gas there were lots of questions and an hour later we would get out of there.”

Simpler Living

It was noted as early as the 1970s that every technological advancement in society creates a counter movement toward a simpler version of that technology—sort of a social Newton’s Law that every action has a reaction.

For example, highly automated industrialized agriculture helped create increased demand for free-range, small-scale sustainable farms, while advanced computer technology creates a desire among some to get outdoors and off the grid.

Perhaps Doug and Malcolm McNair and their merry band of old car fanatics are a reaction to the modern computer-controlled automobiles. It’s a desire to return to a time when a Sunday drive truly was a simple adventure.

Tim Hauserman is a Tahoe City–based writer. While he knows very little about cars, he is inspired by those who do. A highlight of 2018 was a ride in Doug McNair’s 1909 Chalmers-Detroit.

No Comments