05 Oct Shane McConkey’s Lasting Legacy

A decade since his last stunt, the Tahoe freeskiing legend is remembered for his beaming spirit, incredible talents and revolutionary contributions to his sport

Beginning in 1995, Shane McConkey ruled as king of the skiing world for the better part of the next decade and a half, while also serving as its jester.

One of the greatest skiers of all time, not to mention one of the best Tahoe athletes in any discipline, the late Squaw Valley icon carved out a unique spot in the region’s athletic pantheon. He simultaneously ascended to the pinnacle of his sport while mercilessly skewering and satirizing its sanctimonious self-seriousness and inherent ego.

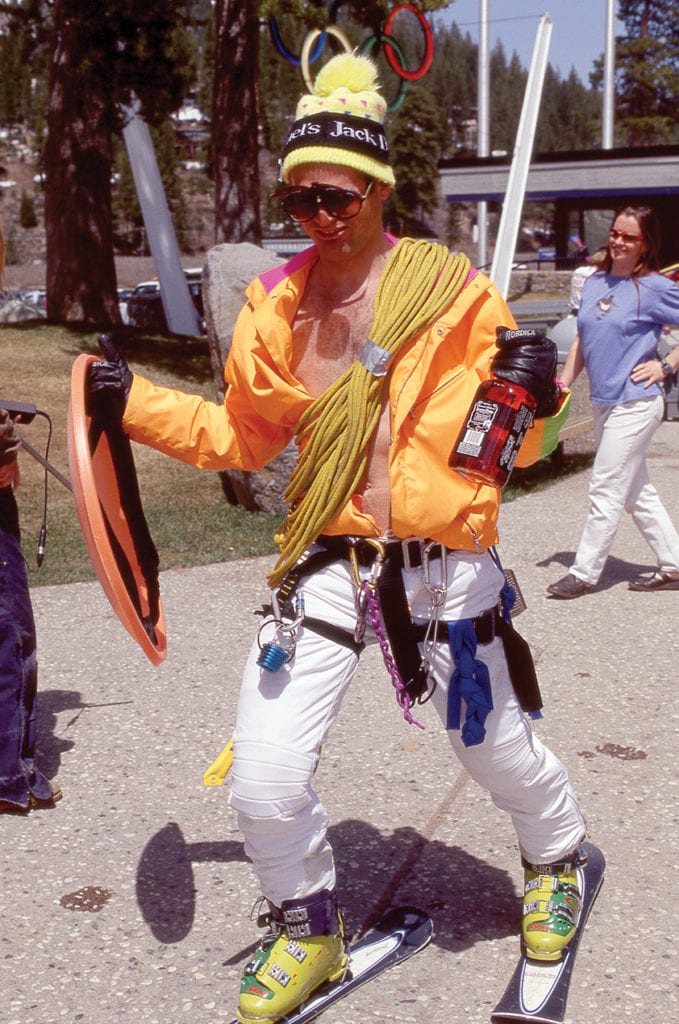

“I can stick uphill ice on my saucer,” McConkey famously said while dressed in the neon apparel of his Jack Daniels–wielding alter ego, Saucer Boy, intended as a send-up of pro skiers and their arrogance. It wasn’t just Saucer Boy, either, as McConkey willingly played the clown in the nearly two dozen ski videos he starred in over the course of his career. He relentlessly played practical jokes on his fellow skiers, hammed it up for the cameras and frequently skied naked.

Shane McConkey as Saucer Boy, 1998, photo by Keoki Flagg

In fact, McConkey received a lifetime ban from Vail Resorts after hucking a backflip during a mogul competition and proceeding to race his final heat in the nude.

He also invented the game of G.N.A.R., short for “Gaffney’s Numerical Assessment of Radness.” The game, which is detailed in a chapter written by McConkey in Robb Gaffney’s book Squallywood: A Guide to Squaw Valley’s Most Exposed Lines, assigns numerical value to the most difficult and dangerous lines at Squaw Valley—McConkey’s home mountain. Points are also awarded for undertaking various ski-related hijinks, like farting in a crowded tram and claiming it.

Thanks to McConkey, a generation of skiers and snowboarders throughout Tahoe were cruising up to complete strangers and saying, “I’m so much better than you,” or, “I’m the best skier on this mountain”—both of which would earn G.N.A.R. points.

“The ski industry can be a little intense,” says Sherry McConkey, Shane’s widow. “I think Shane influenced the ski industry in a good way. He got it to not take itself so seriously and encouraged people to have more fun, especially when they’re doing the things they love.”

And Shane McConkey loved skiing.

And there’s the rub.

McConkey’s schtick as king of the goofballs, his irreverent spirit that pervaded his personality and his exploits, belied the fierceness of his passion for skiing and his raw ambition to be the best.

“People think he was just an adrenaline junkie going out there and tossing these things off,” says Scott Gaffney, McConkey’s close friend and longtime filmmaking partner. “But it wasn’t that way at all. He worked on it hard.”

While McConkey enjoyed success coming up as a competitive alpine ski racer, his career transcends the trophies won and is more about his courage, his willingness to tackle the most difficult and daring ski lines in the world with a seemingly casual disregard for the stakes.

“Shane was aggressive in his skiing,” says JT Holmes, a Squaw Valley–based skier and aerial athlete who was a close friend of McConkey’s. “A lot of skiers just seem to go through the motions, but Shane always seemed to be charging and learning while he did it. He made the most out of every run.”

As much as McConkey left an indelible imprint on skiing through his physical exploits, it was his mind that continues to have the biggest impact on successive generations of skiers.

He advocated for new ski design, favoring fatter skis with a rockered profile for navigating powder. Scoffed at when first employed, the ski design McConkey championed is now commonplace at resorts across the globe, allowing skiers to float atop the snow rather than sink into it.

“For all those people whose legs are burning at around 1 p.m. on a powder day, they should be thankful, because without Shane, they would’ve burned out by 11 a.m.,” Holmes says.

McConkey was a multi-faceted individual—a prankster with a derelict sense of humor, a world-class athlete bound for greatness, a designer and equipment engineer motivated by the simplicity of function. The strain that ran through all McConkey’s facets was a sneering disregard for boundaries, for limitations—self-imposed or otherwise.

“Shane didn’t see the walls of the box,” Gaffney says. “He didn’t recognize the limitations, and if he did see them, he looked for ways to push them.”

McConkey’s disdain for the box revealed itself in his penchant for increasingly daring aerial stunts. Immediately struck by the freedom and beauty of skydiving, he soon turned to BASE jumping from bridges, cliffs, buildings or whatever formation offered a creative way to jump, fall, pull a parachute and land safely on level ground.

He found ways to incorporate skiing into aerial athletic pursuits, a dangerous cocktail that ultimately proved fatal, robbing McConkey of his life in 2009 and an opportunity to watch his young daughter, Ayla, grow up.

But as the 10-year anniversary of McConkey’s death approaches in March, the fallen skier’s family, friends and fellow athletes are forced to unfurl a grief that remains untinged by bitterness or what-ifs and instead is full of gratitude for his humor, generosity and how he provided an example of an uncompromised life lived at full throttle.

“I’m getting maximum enjoyment out of life and I’ll never stop,” Shane McConkey once said.

McConkey on Eagle’s Nest (aka “McConkey’s”) at Squaw Valley, 1996, photo by Keoki Flagg

Squaw Heritage

“Shane was Tahoe and Tahoe was Shane,” says Ingrid Backstrom, an accomplished freeskier who frequently appeared alongside McConkey in various Matchstick Productions films. “Shane as much as anyone showcased what Tahoe had to offer. Whether it was the Palisades at Squaw or the backcountry, that was his playground.”

Matchstick Productions director Scott Gaffney, who moved to Tahoe the winter of 1994–95 to pursue his film career, says Squaw Valley is the place where McConkey went from a relatively anonymous skier to a legend.

“We shot Walls of Freedom (1995) with a bunch of Tahoe locals, but Shane was just a level above. We shot two films that year and Shane made his mark—1995 was the year Shane became the man,” Gaffney says, adding that Squaw, and by extension the rest of Tahoe, was the epicenter of the ski movie industry in the mid 1990s. “It was the place of ski movie dreams. There’s just a ton of skiable snow and a whole lot of sunshine.”

By then, however, Squaw’s freeskiing roots were already well established. Far before McConkey and his contemporaries ever made a name on the resort’s famously burly terrain, Squaw’s most hairball lines were pioneered by earlier generations of fearless freeskiers—like Craig and Gregory Beck, Mark and Tuck Rivard, and David Burnham in the 1970s, who ushered in future waves of professional freeskiers the likes of Glen Plake and Scot Schmidt.

“Back then, there were not a whole lot of guys doing it,” says Schmidt, who moved to Squaw in 1979 before going on to star in dozens of ski movies. “You could put a track down through the Palisades, or the Chimney or Eagle’s Nest, and it would stay there through the next storm.”

The beauty of those iconic Squaw features, both then and now, is that they are all in plain sight from the chairlifts.

“It’s quite the arena,” says Schmidt, for which “Schmidiots,” a 67-degree, 100-foot line on the Palisades is named. “People are always watching from the lift, from the ridges. To have such huge audiences pushes people.”

Given Squaw’s rich freeskiing history, by the time McConkey arrived in 1995 virtually all of the resort’s daring lines had been taken.

“I think a lot of people were interested in seeing what type of impact Shane would have at Squaw,” Gaffney says. “But after living here for only one year, he changed everything here.”

It’s not that McConkey discovered challenging new terrain at Squaw. For the most part, he skied the same lines as his predecessors. But he did it with an entirely different flair, often involving a giant, laid-out backflip.

“Shane took what we did and added a whole other dimension to it,” Schmidt says. “He was doing the same lines, catching the same air, but with spins and flips. For us, we were gripped just to do these lines.”

McConkey in his comfort zone, photo by Keoki Flagg

The Formative Years

While McConkey moved to Squaw Valley at age 24 to make his mark in freeskiing, it was hardly his first time there. He grew up skiing at Tahoe resorts.

“He lived in Santa Cruz and he and his mother would go up to Squaw on the weekends,” says Sherry McConkey. “Sometimes he would stay with families around Truckee, especially after it became apparent he was becoming a really good skier.”

McConkey was born in Vancouver, British Columbia. His father, Jim, and his mother, Glenn, were both living the ski bum lifestyle in and around Whistler at the time.

Jim McConkey was a noted alpine star, appearing in ski films in the 1960s while instructing at Whistler. But he was not in his son’s life much after Glenn, a notable slalom skier in her own right, left Canada and took her 3-year-old child to the Central Coast of California.

While not as ensconced in the skiing world in Santa Cruz, Glenn still took her son up to the mountains frequently.

The young McConkey quickly took to alpine racing with the goal of one day competing in the Olympics like Sweden’s Ingemar Stenmark, his ski racing idol in his youth. McConkey spent his high school years honing his talents at the prestigious Burke Mountain Academy in Vermont.

But it was not to be.

McConkey was a late developer who lacked the prototypical size of a World Cup ski racer. Realizing his dream of becoming an Olympian was unlikely, he gave up the discipline and enrolled at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

“He had focused his entire life on ski racing, so for him not to make it was a huge downer in his life,” Sherry McConkey says. “He had a hard time in college; he didn’t really like school at all. He knew what he wanted to do in life, what he was passionate about. He just had to find a way to do it his way.”

Having dropped out of college, McConkey was living in the basement of fellow skier Kent Kreitler’s house, delivering pizzas at night and eliciting general concern from his relatives and peers about the trajectory of his life.

He had made the transition from racing to mogul skiing, winning a Pro Mogul Tour event in 1993.

“The thing about Shane was he was super competitive,” says Kreitler, adding that he often brought a ski racing mentality to freeskiing.

Meanwhile, McConkey’s athletic feats on the mountain—the flips, spins and gnarly lines tackled with precision—earned him sponsorships with ski companies Volant and Spyder.

Inspired by cult classic ski films such as Blizzard of Aahhh’s (1988), starring Schmidt and Plake, McConkey gravitated toward the camera. He and Kreitler began skiing in some films, including two by filmmaker Nick Nixon. But when McConkey played a prank on Nixon that didn’t go over well, the relationship dissolved, according to Gaffney and Kreitler.

However, in the meantime, McConkey delivered a pizza to a young medical student named Robb Gaffney—Scott Gaffney’s brother. McConkey spotted Robb Gaffney’s skis and the two got to talking. They became fast friends before Robb introduced McConkey to his brother, cementing one of the great ski filmmaking partnerships in the sport’s history.

“Shane always said he would be nobody without Scott Gaffney,” Sherry McConkey says. “He felt he was a genius at filming and that he made him famous.”

So when Gaffney moved to Squaw the winter of 1994–95, convincing McConkey to join him wasn’t a hard sell. After all, McConkey had just been banned from Vail and booted off the pro mogul circuit after he hucked an illegal backflip and snuck back into the competitor’s line to take one final run naked—punctuated by a spread eagle for style.

Shane McConkey, 2007, photo by Court Leve

McConkey the Prankster

Everyone who knows McConkey was either a victim or accomplice to his pranks.

“There was never a dull moment with Shane,” Sherry McConkey says. The wife of the notorious prankster admits she wasn’t always in the mood for it, whether it was hopping out of the shower while she was brushing her teeth, or running ahead on the trail and popping out of the woods to startle her. “He loved trying to give me a heart attack,” she says.

Ingrid Backstrom recalls a birthday party of hers in Portillo, Chile. Her friends assembled around a table with candles and all the trappings. After Backstrom blew out the candles, McConkey presented her with a gift.

“I opened it up and it was one of Ayla’s poopy diapers,” Backstrom says.

Cody Townsend, another freeskier who frequently skied with McConkey at Squaw Valley, recalls getting home to his girlfriend one day and she was demanding answers regarding a note from someone claiming to have had a one-night stand with Townsend in the recent past. The handwriting of the enigmatic mistress was mysteriously similar to McConkey’s.

Gaffney remembers climbing at Big Chief in the Truckee River Canyon one day with McConkey. On the way back from the cliff, they stopped by a buddy’s house, who made the mistake of not being home.

“We snuck into his house and turned every poster upside down,” Gaffney recalls. Nothing big, just moving things around subtly enough to suggest maybe a poltergeist had moved in.

Even death could not tame McConkey’s relentless pranking.

“We had this running joke among the crew that we would run up each other’s hotel bills or play credit card roulette for helicopter bills,” Holmes says. “Another one was stealing money from people’s wallet and waiting until they had to pay for something.”

Holmes was with McConkey in Italy at the time of his death.

“It was brutal. I was a long way from home and my best friend had just died,” Holmes says. “Getting ready to go home, I notice that my money, my credit cards and all my receipts are missing.”

Holmes chalked it up to one more in a series of abysmal events, but as he rifled through his and McConkey’s gear at the London Heathrow airport in an attempt to organize it all, he had an epiphany.

“I look in Shane’s wallet and sure enough, there was my money, my credit card and receipts,” Holmes says. “He pulled the trick one last time.”

Fateful Fall

The Spy Who Loved Me (1977), the popular James Bond movie starring Roger Moore, features a famous chase scene on skis. Maneuvering gracefully, Bond manages to dodge gunfire from the bad guys following closely on his heels. Right as it seems the henchmen are about to overtake the embattled hero, Bond launches off an enormous cliff. He appears doomed—that is, until he pulls a cord that releases a bright red parachute that carries him to safety.

This sequence was central to McConkey’s imagination as a kid and an adult. And the stunt, performed by Tahoe BASE jumper Rick Sylvester, was something McConkey longed to recreate. With this in mind, he began combining skiing and BASE jumping.

At Lover’s Leap, near Echo Summit on the South Shore of Lake Tahoe, McConkey and Holmes first tinkered with skiing off cliffs and pulling parachutes.

“There is nothing better in life than sliding down snow before flying through the air,” McConkey once said.

It was this love of skiing and BASE jumping that led McConkey and Holmes to the Dolomites in Italy, where the Sass Pordoi, a 9,685-foot, table-like cliff system protrudes vertically from the ground. More popular with hikers than skiers, the cliffs include a skinny couloir that Holmes and McConkey skied down before reaching a precipitous drop that falls thousands of feet. McConkey had already jumped the cliff in the summer and had been chomping at the bit to ski BASE it.

The two men dropped rocks and counted the seconds before they hit in an attempt to judge the height. Ultimately, the method proved faulty, as there was not as much room between the cliff and the ground as they thought.

Holmes went first.

“We misjudged the height of the cliff,” Holmes says. “I was surprised with how quickly the ground came up on my jump.”

But it wasn’t just height miscalculation. When McConkey’s turn came, he performed two backflips before trying to pull his skis off via a cord attached to his bindings. When ski BASE jumping, flips are more than just style points. They are essential to keep aerial movements manageable.

“It’s difficult to stay on top of your skis for a long time in the air,” Holmes says. “When you perform flips, you introduce this symmetrical movement that makes everything more predictable.”

When McConkey came out of his backflips and pulled the cord, his left ski failed to come off—which is essential before pulling the chute because it could become tangled with the ski. This particular scenario was compounded by the fact that the left ski was entangled with the right.

Ever air aware, McConkey kept from panicking and calmly managed to get the left ski off. He turned to the ground with the intention of pulling the chute, but he didn’t have time. He was hurtling toward the ground at 110 miles per hour and he had less room than anticipated.

He impacted the ground without ever pulling the cord. Shane McConkey was dead at the age of 39.

McConkey BASE jumps off the Silver Legacy in Reno, 2007, photo by Court Leve

Aerial Pursuits

It’s easy to second-guess athletes who live on the edge of life and death, particularly when something goes wrong.

“We were naive with the whole BASE jumping thing,” Sherry McConkey says. “We’d only heard of Jan Davis dying in Yosemite.”

McConkey learned to BASE jump from Frank “The Gambler” Gambalie, an accomplished Tahoe skydiver and BASE jumper in the 1990s. Gambalie drowned in the Merced River in 1999 after he dove in trying to escape park rangers in Yosemite National Park, where BASE jumping was illegal and carried heavy fines. During a jump the same year from Yosemite’s El Capitan, which was intended to honor the life of Gambalie while protesting the park’s ban on the sport, Jan Davis died after her parachute failed to open.

It was a wakeup call, but many in the sport felt McConkey was too skilled to ever suffer a similar fate.

“Shane was the guy we all thought was never going to die,” Townsend says. “He was too air aware, too perfect.”

Holmes says it took a perfect storm of things going wrong for it to happen, but his death proved just how slim the margin for error is in that sport.

“You don’t get to crash in that sport,” says Scot Schmidt. “All it takes is one mistake. And you don’t learn from your mistakes the way you do in skiing. You die from your mistakes in that sport.”

But for McConkey, the airborne sports were just part of his outsized lust for life.

“He was already pushing the limits in every other way,” Gaffney says. “For Shane, it was just the next step in a natural progression.”

Gaffney says the general public will never understand how much work McConkey put into each jump. He went skydiving with skis several times in order to figure out the best way to manage them in the air. He conducted voluminous amounts of research about potential jumps.

In the end, however, no amount of planning or skill could forestall the inevitable.

But Sherry McConkey doesn’t spend her time with what-ifs. Instead of feeling bitter, she prefers to be proud of her husband’s ability to seize the day.

“When he was a kid, in high school, he filled out this paper about what he would have to do to get the maximum enjoyment out of life,” she says. “He ended up doing all of them. How cool is that? He did more with one life than most people could do with 10 lifetimes.”

For many of McConkey’s peers, the aerial pursuits were just part of his larger-than-life persona.

“Shane is one of the godfathers of that sport,” Townsend says. “They have moves called the McConkey in that sport. How many athletes can say they revolutionized two sports?”

But for the skiing purists who witnessed McConkey’s exploits, the airborne stuff was just sideshow.

“The BASE jumping may have stole some thunder from the skiing,” Gaffney concedes.

Holmes agrees: “I think his biggest accomplishments were in skiing, not the airborne sports. He was at the top and we were all just chasing his heels.”

McConkey with a sizable spread eagle at Squaw Valley, photo by Keoki Flagg

Skiing Ability

“Versatility is what really separated Shane,” says Kreitler. “I mean, he won a competition on the mogul tour, could big mountain ski, do all the aerial stuff. I mean, you got guys who can ski big mountain features but can’t flip. Shane could do it all.”

After achieving modest success in alpine racing as a youth, and in mogul competitions later, McConkey became an international star through his freeskiing accomplishments. He consistently landed on podiums in freeskiing competitions throughout the late 1990s and in 2001 was named ESPN’s Action Sport Awards Skier of the Year. In 2002, he won POWDER Magazine’s reader poll for his revolutionary powder ski design.

While the hardware is significant, McConkey was always more about the films and the persona.

“He has an amazingly fluid style, making it all look very effortless while going completely balls to the wall,” Townsend says. “You don’t see that combination very often. Usually, you have the chargers that lack the grace or guys who are very fluid but are reluctant to go big.”

Kreitler says it stems from McConkey’s stint at Burke Mountain Academy, where he trained in slalom before applying those principles to the creative discipline of freesking.

“He had a skinny upper body, but he had extremely strong legs,” Kreitler says. “His body was actually ideal for skiing.”

Sherry McConkey says her husband often discussed the benefits that ski racing had on his later career.

“Training for ski racing made him what he was,” she says. “He always said it was important to race before heading to the big mountains, so you could learn technique and how to use your body to get out of various situations.”

For Backstrom, McConkey’s confidence in his ability stood out.

“He always knew what he could do and what he couldn’t do,” she says. “He could always pick out the line that was best for his ability and flash it. His percentage of nailing the line was the highest of anyone I’ve ever been around.”

McConkey introduced wider skis designed specifically for powder, photo by Hank de Vré

Ski Genius

For all of McConkey’s contributions to the kinetic aspects of skiing, it was his hardheaded insistence on bringing the sport into the twenty-first century that is arguably his biggest contribution to the industry.

After tinkering for years with the concept of a wider ski designed specifically for powder, with reverse camber and reverse sidecut, McConkey convinced his sponsor, Volant, to manufacture the Spatula in 2001. While many wrote off the design initially, the ski gained wide support and ultimately revolutionized powder skiing.

“That’s what was great about Shane,” says Schmidt. “People were laughing at those Spatulas when they first came out, but he didn’t care. I mean, they work and they’ve gone mainstream pretty quickly.”

Adds Backstrom: “The new shape of skis blew people’s minds as to what was possible. It really opened up skiing big mountains.”

For Sherry McConkey, it also provides a window into her husband’s sometimes stubborn convictions that his way was the right way. “One of the things I loved about him was that when he had an idea, he made it happen.”

“I think he was a genius,” adds Holmes. “He was just one of those geniuses that was never going to do well in school.”

Shane McConkey with daughter Ayla, 2009, photo by Keoki Flagg

Shane McConkey with daughter Ayla, 2009, photo by Keoki Flagg

Remembering Shane

This ski season will be the 10th without Shane McConkey hucking flips from Squaw Valley ridgelines.

But his influence remains.

“I think Shane truly embodied that spirit that life is about being happy, and you should do the things that make you happy,” Townsend says.

It’s no mean feat in an industry that sometimes puts more emphasis on a cool arrogance or a competitive intensity.

Backstrom remembers McConkey for being an incredible team player, rooting people on during the long shoots up in Alaska or at Squaw.

“He was incredibly kind and caring and he was a huge mentor to me,” she says. “He loved to help others reach their potential and wanted everyone around him to be lifted up and have a good time.”

For Holmes, McConkey was his best friend, adventure partner and the genuine article.

“First of all, how you see him in all the videos, that’s exactly how he was in real life,” Holmes says. “He’s not like a lot of guys selling tickets to a fake show. That wasn’t him.”

It’s something reiterated by many people who encountered McConkey through the course of his life.

“People say don’t meet your heroes, but Shane was the exception to that,” Townsend says.

Kreitler says he drifted away from McConkey once they moved to Squaw together, but saw his old friend mature into a good man and father in his final years.

“I remember when I wrote to him telling him I was retiring, it was like getting out of skiing with a clear conscience,” Kreitler says, describing an email he wrote to McConkey a few months before he died. “We were always competing with each other and it was my way of telling him, ‘The competition is off.’”

Kreitler says McConkey wrote back saying he respected the retirement decision, but he still had some goals left to achieve.

McConkey was slowing down though. He’d had seven knee surgeries, a brutal back injury and countless other injuries. Sherry McConkey says in his last years, he was increasingly more concerned about spending time with Ayla.

“He was thinking about his future, thinking about slowing down,” Sherry says.

Holmes says he has pumped the breaks on his own more daring pursuits, leaving it to the younger generation of daredevils. It’s not hard to imagine McConkey opting for a similar path.

But Sherry can’t go there, instead concentrating on honoring her late husband who was so universally loved, while raising perhaps the best part of his legacy—Ayla, who is on the cusp of becoming a teenager.

“She’s a very cool kid,” Sherry says. “She has a lot of his traits—she’s very kind, very empathetic—but then not some of them. Everyone thinks she must be crazy, must be this ripper running around. But she’s just normal. She likes to surf and dance.”

McConkey is still honored by his peers. The Shane McConkey Foundation donates money to a bevy of organizations in the Tahoe area. The Pain McShlonkey Classic, a race on snowlerblades featuring contestants in outrageous costumes, and the ensuing gala are the signature events that generate the funds.

“It’s hard to lose someone you love,” Sherry says. “But as I saw so many people also grieving him, I felt guilty and I wanted to do something every year to remember him.”

Shane McConkey is not forgotten. He lives on in his ski films, in his contributions to industry design and, above all, his jovial spirit and blithe approach to the sport he loved.

“He was the coolest human I ever met,” Sherry says. “He had the kindest soul and he was an amazing dad and husband.”

Matthew Renda is a Santa Cruz–based writer who is honored to remember the legacy of the late Shane McConkey.

No Comments