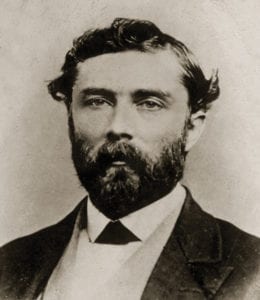

24 Jun Surmounting the Sierra

The festive scene at Promontory, Utah, on May 10, 1869, celebrating the completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad, photo by Alfred A. Hart, courtesy Department of Special Collections/Stanford University Libraries

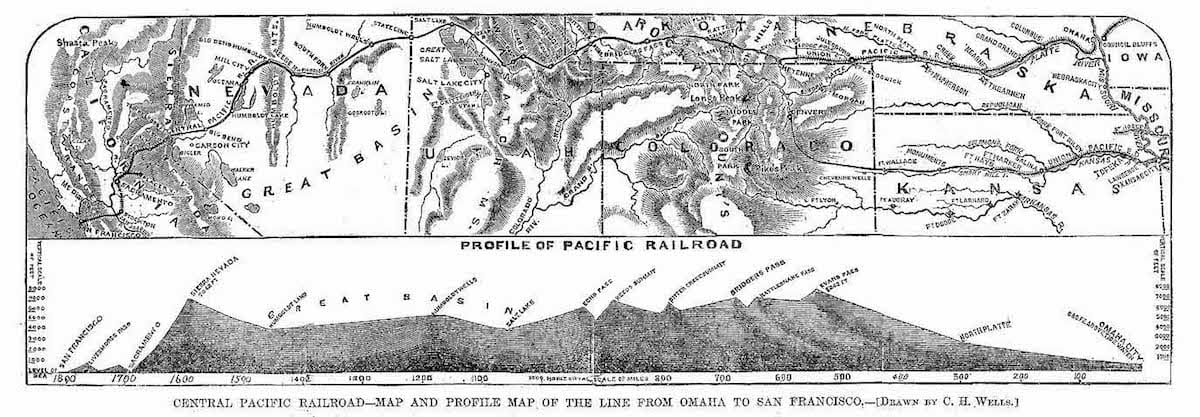

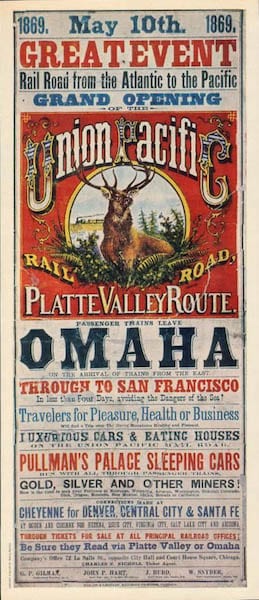

A century and a half after its completion, the First Transcontinental Railroad remains a mind-boggling feat of engineering

When Leland Stanford hoisted a silver-plated hammer above his head in a remote patch of uninhabited Utah, the world awaited his strike.

The American West was only recently connected to the rest of the nation by telegraphic wires, and ceremony organizers had contrived to put one telegraph sensor on the hammer with the other placed on the golden spike. When the two connected, it would transmit a message instantaneously to all corners of the United States.

Fixing the wire at Promontory, Utah, on May 10, 1869, photo by Alfred A. Hart, courtesy Department of Special Collections/Stanford University Libraries

The announcement of the First Transcontinental Railroad’s completion would alert the entire nation, which had only recently been reunited from north to south, that it was now joined from east to west.

The silver hammer striking the golden spike would signal the completion of the first large government-funded infrastructure project in the United States—and one of the greatest engineering feats in human history. It would mark the unlikely realization of ambitious dreams, the political will of the nation’s greatest leaders, an appetite for risk among some of the leading businessmen, and the determination, coordination, persistence and muscle of a multinational workforce of men unequaled in that century or since.

It was May 10, 1869. The day was clear and the sky, after a few days of steady rain, was a bright blue.

Situated as it was before the days of radio, television or the Internet, citizens of the young nation were unused to knowing about events of such magnitude, much less the moment they happened. Thanks to the telegraph, such a thing was possible.

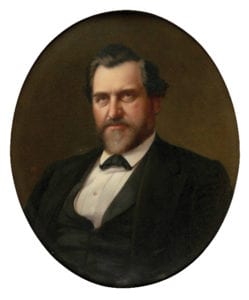

Leland Stanford

One problem did materialize, though. Stanford missed the spike, striking the rail instead. No matter. The telegraph operator closed the circuit and the message was transmitted throughout the vast telegraphic network that reached dozens of cities in the United States and all the way to London.

In San Francisco, the celebrations began on May 8 and ran through the day of the Golden Spike, as the “City by the Bay” had much to gain from a reliable transportation connection to the East. In Chicago, they held a 4-mile-long parade. Philadelphia rang the Liberty Bell for an hour. New York celebrated by firing 100 guns into the air. In fact, so many guns and cannons were fired across the the United States that day, commentators remarked that more gunpowder was likely expended than during the Battle of Gettysburg.

The exaltation was warranted, as the Golden Spike marked a watershed moment in the country’s history. The thin ribbon of iron that ran from Omaha to Sacramento marked the nation’s confident entrance into the industrial phase of its future.

It connected Western settlers back home. Instead of mail taking months, it took days.

Before the transcontinental railroad, those on the East Coast hankering to reach California could go one of three ways, all of which took months and carried an abundance of dangers—overland with the specter of thirst, hunger and hostile natives; sailing around Cape Horn at the south end of South America; or using the shortcut over the Panama isthmus with its jungle and deadly fevers.

The Emigrant Gap Tunnel, wall and snow shed along the Central Pacific line over the Sierra, photo by Alfred A. Hart, courtesy Department of Special Collections/Stanford University Libraries

The railroad also fully unlocked the economic might of the mineral-rich West, with its gold, silver and fertile agricultural land, the product of which could finally be shipped to all corners in a timely manner.

But most of all, it forged a continental bond for the young American nation and truly cinched the promise of Manifest Destiny.

As Walt Whitman wrote of the railroad in a poem published in 1870:

The earth to be spann’d, connected by network,

The races, neighbors, to marry and be given in marriage,

The distant brought near,

The lands to be welded together.

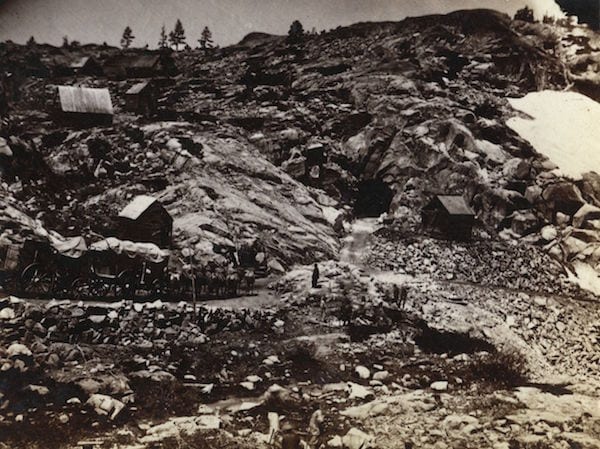

Long Ravine Bridge near Colfax crosses 120 above the ravine below, photo by Alfred A. Hart, courtesy Department of Special Collections/Stanford University Libraries

The Dreamer

In a complex enterprise involving such a vast throng of workers, superintendents, foreman, surveyors, engineers, chemists, inventors, capitalists, financiers, politicians and visionaries, it would appear ridiculous to single out one man as the individual responsible for bringing about the Transcontinental Railroad.

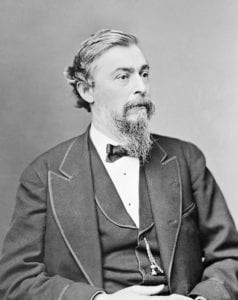

Theodore Judah

But if one were forced to choose, that man would be Theodore Judah.

Today, skiers who flock to Sugar Bowl Resort on Donner Summit often journey to the top of the mountain named in his honor without knowing the instrumental contributions he made to the region and the nation as a whole.

Unlike many of the men remembered from that era, Judah was not a robber baron, someone with ready access to capital or a particularly well-connected man who could grease the wheels of politics. Instead, he was a dreamer, a man they used to call “Crazy Judah,” who had the impudence to envision the Transcontinental Railroad and the guts and tenacity to see it through.

The idea of a railroad connecting the East to the West had gained currency in public discourse first in the 1830s, but the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill outside Coloma in 1848 and the subsequent California Gold Rush only increased the demand for rapid and convenient transportation across the continent. However, a bitterly polarized Congress in Washington D.C. made the prospect of such an enormous national infrastructure project seem infeasible.

Nevertheless, in the early 1850s when Judah was living in Buffalo, New York, working as a railroad engineer on the Erie Line, he remarked to his wife Anna, “It will get built and I will have something to do with it.”

Soon after, William Tecumseh Sherman, the famous Union Army general who in the 1850s was the president of the first railroad company in California, hired Judah to come West and help build the Sacramento Valley Line from Sacramento to Folsom.

Soon after, William Tecumseh Sherman, the famous Union Army general who in the 1850s was the president of the first railroad company in California, hired Judah to come West and help build the Sacramento Valley Line from Sacramento to Folsom.

Judah gladly accepted, but more out of the desire to bring to fruition the long-discussed Transcontinental Railroad.

After completing the Sacramento Valley Line, Judah set to work advocating for a transcontinental line so fiercely and persistently that folks began to whisper he was “Pacific Railroad Crazy.”

Despite numerous detractors, Judah succeeded in getting a convention called in 1859 with all the major legislators and businessmen of San Francisco and Sacramento. At the event, it was decided they would build a rail east from Sacramento. Judah would be their ambassador, vested with the task of traveling to Washington D.C. to convince lawmakers of the urgent necessity to build a line joining the two flanks of the continent.

Along with the help of his wife, whose sketches and paintings of the Sierra lined a museum the pair established in D.C., Judah set about convincing federal lawmakers that such a prospect was possible.

He was met with incredulity.

The fate of the Donner Party and other much-broadcasted incidents of pioneers and their difficulties crossing the Sierra Nevada were such that most regarded any attempt to get trains over the rugged mountain range as futile. But Judah knew it was possible.

With the persistent refrain of doubters in his mind, Judah repaired back to California determined to survey the exact line by which his railroad would surmount the formidable range.

The engineer spent the entire summer of 1860 in the Sierra, getting to know its contours and topography with a zeal and intimacy perhaps only matched by the likes of John Muir—although Judah was less interested in botany and mystic evocations, and instead focused intently on the engineering problem presented by the rugged terrain.

Nevertheless, he wrote to his wife about the joy he experienced breathing the sharp mountain air, contemplating potential positions for a line while resting next to a campfire only to drift to sleep beneath bright stars and towering pines.

Dutch Flat, photo by Alfred A. Hart, courtesy Department of Special Collections/Stanford University Libraries

Judah checked Henness and Beckwourth passes, neglecting Donner Pass mostly because of the story of the Donner Party some 15 years earlier. Meanwhile, a druggist in Dutch Flat by the name of Daniel Strong, who most called Doc, heard about Judah and his dream. Strong, a notable mountaineer, knew the best route for a train over the Sierra spine was, in fact, Donner Pass.

The route was superior because it differed from the rest of the Sierra crest, which was typically comprised of parallel ridgelines separated by steep valleys, meaning any train would have to summit twice. The Donner route featured a plateau at the crest, meaning a train only had to achieve the summit once before descending the opposite side.

Strong reached out and connected with Judah as autumn approached in 1860. The two men forayed into the upper elevations near Donner Summit, with Judah spending his days making a detailed survey of the area.

Early one morning before sunrise, the pair was awakened in their darkened camp by an early-season snowstorm. They mounted their horses and hurried back to Strong’s place in Dutch Flat beneath the snow line.

Secrettown Trestle stretches 1,100 feet across the ravine below, photo by Alfred A. Hart, courtesy Department of Special Collections/Stanford University Libraries

Upon arriving, Judah forwent sleep and immediately set about making his calculations and drawing charts. When the sun was high in the sky he looked at his friend and said: “Doctor, I shall make my survey over this, the Donner Pass.”

With the line identified, Judah next turned his attention to the challenge of funding.

After getting laughed out of boardrooms all over San Francisco, he tried Sacramento to greater avail. Giving his presentations to men of ample means, he finally caught the interest of four storekeepers who had come to California during the Gold Rush and made their respective fortunes providing provisions and goods to the profusion of miners in the West.

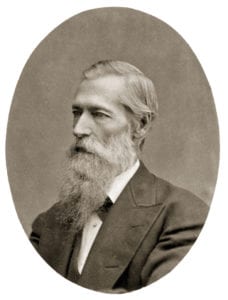

Charles Crocker, Collis Huntington, Mark Hopkins and Leland Stanford were interested in Judah’s dream, but were driven more by the chance to obtain goods for their businesses at a cheaper price with greater rapidity than any great notions of national destiny.

So in June 1861, the Central Pacific Railroad was founded with Stanford named president. Meanwhile, Judah traveled to Washington D.C. to drum up the capital needed for an ambitious project that all involved knew would only succeed with the assistance of the United States government. However, the men felt a gleam of confidence, largely due to the recent inauguration of Abraham Lincoln.

Blasting a cut 60-feet deep at Chalk Bluffs above Alta, photo by Alfred A. Hart, courtesy Department of Special Collections/Stanford University Libraries

Abraham the Railroad Man

Lincoln will be forever known as the man who abolished slavery in the United States. But the Great Emancipator started his career as a railroad lawyer.

Born in Kentucky, Lincoln was self-educated, teaching himself to read and voraciously consuming whatever books were on hand. Despite a lack of formal education, Lincoln was admitted to the Illinois bar in 1836. Four years earlier, in 1832, Lincoln launched his political career running for the Illinois state legislature on the platform of bringing the railroad to undeveloped parts of the state.

He lost. But Lincoln’s belief that railroad development was vital for the U.S. economy would follow him throughout his legal and political career.

After he gained prominence as an excellent orator and astute legal practitioner, he became the go-to for railroad companies throughout the 1850s, often representing the Illinois Central in landmark cases that established the property rights of railroad companies, among other issues.

As the presidential candidate for the Republican Party, Lincoln signed off on the platform that stated “that a railroad to the Pacific Ocean is imperatively demanded by the interests of the whole country; that the federal government ought to render immediate and efficient aid in its construction.”

The second part was important for Judah and his quest to secure government funding for a project requiring enormous up-front expenditures before a single cent of revenue would ever roll in.

Lincoln was elected president in November 1860 and by the time he was inaugurated in March 1861, the Southern states had seceded and formed the Confederacy.

While the secession presaged the horrors of war and bloody discord for the nation as a whole, it was a boon for Judah and the backers of the Transcontinental Railroad. Lawmakers had been fighting over the location of the transcontinental railroad for the better part of a decade.

While the secession presaged the horrors of war and bloody discord for the nation as a whole, it was a boon for Judah and the backers of the Transcontinental Railroad. Lawmakers had been fighting over the location of the transcontinental railroad for the better part of a decade.

In 1853, Congress authorized $150,000 to then Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, who would become president of the Confederacy, to commission surveys from the 49th parallel to the north to the 32nd parallel in the South. Davis eventually concluded the southern route from New Orleans, through Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and terminating at San Diego, was superior due to the lack of high mountains and snow.

While this was true, no northern senator was going to vote for a line that would materially benefit the slave states.

So the impasse persisted until the Southern senators walked out of Congress, allowing the remaining lawmakers representing the northern states to pass the Pacific Railway Act of 1862.

The law was practically written by Judah, who had long harbored designs about how to best raise sufficient funds for the enterprise. While the law was amended frequently in the following years, the central thrust of the legislation remained. The idea was to grant alternating pieces of land to both the government and the railroad for every mile of track that was laid—hence the checkerboard land use pattern in the Sierra was born.

The government would also provide a certain amount of bonds per mileage to help defray the costs for private investors.

But the most important thing the law did was set up construction as a race. It stipulated that Judah’s Central Pacific would begin building east from Sacramento, while the Union Pacific would start out in Omaha, Nebraska, and head west. The idea was to incentivize both companies to build as quickly and efficiently as possible, and whichever corporation built more would get more. And so the race began.

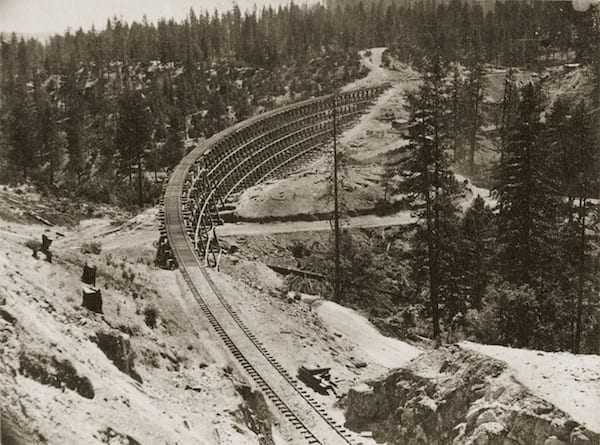

Union Pacific

Upon first blush, it seemed the Union Pacific possessed the upper hand. After all, building track across approximately 500 miles of Nebraska prairie is far easier than attacking the craggy and granitic Sierra Nevada.

Thomas “Doc” Durant

But the Central Pacific was better organized and got an earlier start.

The Union Pacific was led by Thomas “Doc” Durant, an extravagant Wall Street speculator who was more interested in personal profit than bringing the infrastructure project to fruition. Skeptical the railroad would ever be built or make money, Durant founded a construction company called the Credit Mobilier of America to milk the government and pay enormous dividends to himself and his cronies in what eventually proved to be the biggest financial scandal of the nineteenth century.

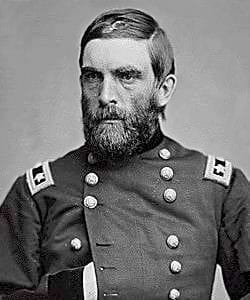

Grenville Dodge

However, the Union Pacific was eventually rescued by Grenville Dodge, who took over the project in 1866 and brought much-needed order to the endeavor.

Dodge was to the Union Pacific what Judah was to the Central Pacific. He was the opposite of Durant, a methodical man with an engineering background who had long dreamt of a transcontinental railroad. Before he joined the Civil War as a general, he had surveyed potential lines west of Omaha, where he lived and maintained a family farm.

During the war, he served directly under Ulysses S. Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman. His principal role in the war—and a vital one at that—was to repair railroad lines and downed trestles compromised by the enemy so that munitions, supplies and reinforcements could be moved about in an expedient and strategic manner.

Dodge translated the engineering acuity and organizational discipline he acquired in the war to the Union Pacific efforts to great effect. His labor force was made up of many veterans of the Civil War, from both the Union and Confederate side, and it showed in the discipline with which they carried out their duties.

Collis Huntington

Unrealized Vision

While Judah was happy to secure the government funding necessary to execute his vision, all was not well in California.

The Big Four—Stanford, Huntington, Hopkins and Crocker—were at odds with the engineer, and their differences were growing increasingly acrimonious.

Charles Crocker

While two factions within the company fought over nearly everything, the divide essentially came down to the fact that Judah believed the project to be his, with the capitalists simply providing the money, while the Big Four believed they were the rightful owners of the railroad and Judah should work at their direction in exchange for a handsome salary.

Mark Hopkins

Their meetings soon devolved into shouting matches, and at one point Huntington told Judah the only way to get his way would be to buy out the Big Four at $100,000 each. It was likely hyperbole, but Judah took it literally, and after some preliminary communications with Cornelius Vanderbilt, he headed to New York to see if he could secure funding to buy out his bosses.

Having traveled across the country several times, Judah always elected for the shortcut over Panama despite the dangers of fever. But on the last voyage, a torrential rain forced him to exert himself helping other passengers while also securing his own belongings. He caught a fever, and after landing in New York he was dead within a week, in his last moments reflecting how he would never live to see his passionate dream materialize.

Assault on the Sierra

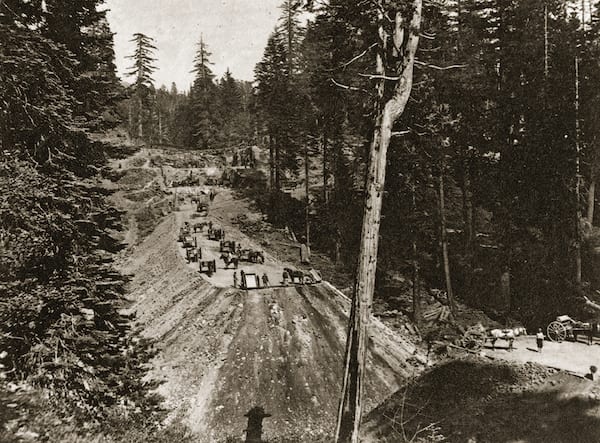

But the Big Four trundled on. They promoted Samuel Montague and Lewis Clement, two engineers hired by Judah, to carry out the work in the Sierra.

Trestle construction near Newcastle, photo by Alfred A. Hart, courtesy Department of Special Collections/Stanford University Libraries

A good majority of the engineering community around the country continued to believe the project would fail.

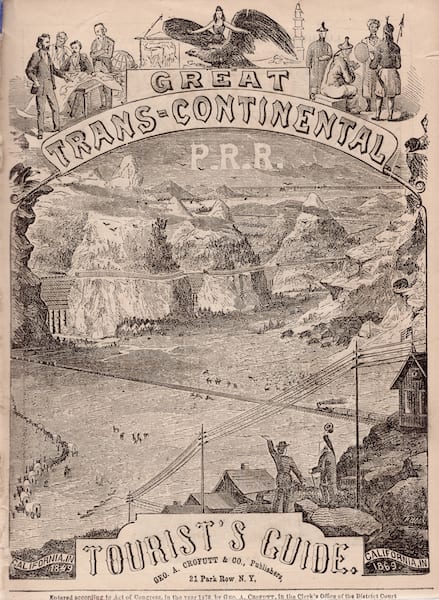

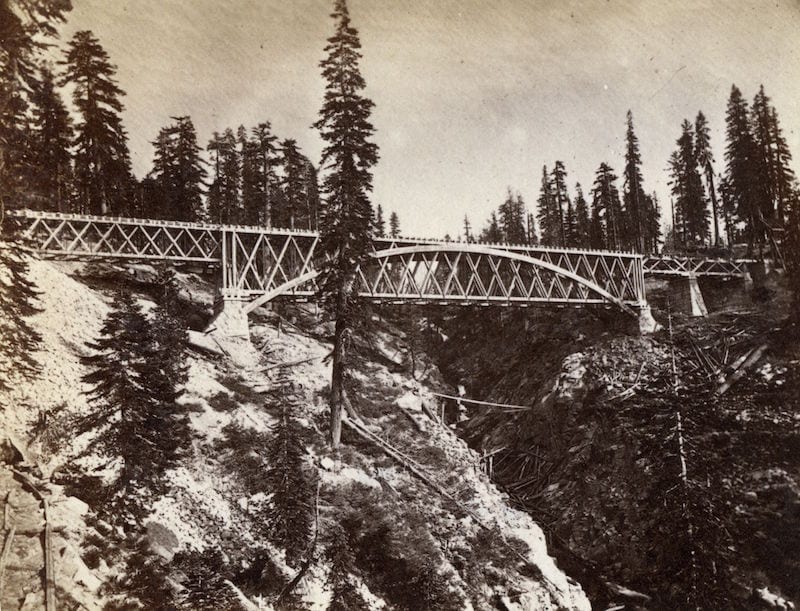

Nevertheless, Judah’s successors saw the establishment of the line from Sacramento to Colfax by 1865. While certainly progress, the real challenge in the Sierra was getting a line running from Colfax to Donner Summit. It would require cutting into the sides of mountains, building numerous bridges and trestles, and boring enormous tunnels through solid granite.

One major hurdle the Central Pacific had to overcome at this juncture was the inconsistency of its workforce. It could not keep men on the line. Nevada’s Silver Rush was still fully active after the Comstock Lode was discovered in 1859. So many of those working on the line for the Central Pacific would work for a week, then take their first pay to buy supplies necessary to unearth silver.

The problem exasperated Crocker, the member of the Big Four who oversaw construction, and his superintendent of construction, James Harvey Strobridge. Crocker suggested giving Chinese laborers a try, but Strobridge balked for reasons of racial animosity mixed with doubts about whether Chinese men possessed the braun necessary to perform the arduous physical labor.

Running out of viable options, Strobridge gave the Chinese a try. They soon proved their mettle and their worth.

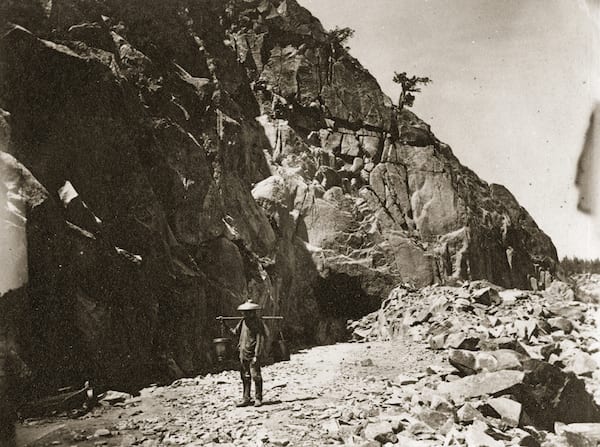

A Chinese tea carrier stands near the east portal of Tunnel 8 on Donner Summit, photo by Alfred A. Hart, courtesy Department of Special Collections/Stanford University Libraries

What they presumably lacked in muscle, they made up for in coordination and teamwork. Also, the Chinese proved ideal workers in other ways.

They showed up for work promptly every morning, and exhibited a willingness to work tirelessly throughout the day without breaks. They proved generally more peaceable than their white counterparts, refraining from physical fights and staying away from whiskey.

Instead, the workforce would indulge in opium on Sundays as a means of relaxation. Their diet also helped. They swore off the Central Pacific rations of boiled meat and instead bought their own food from storehouses in San Francisco, meaning they ate healthier with less susceptibility to sickness and disease.

Their preference for tea, from water that had been boiled, meant they were immune to the dysentery that struck white men accustomed to drinking water straight from the lakes and streams.

Thus, armed with the considerable engineering acumen of Clement and Montague and a reliable and dedicated workforce, the Central Pacific stood ready to mount its attack on the unforgiving granite of the Sierra.

Cape Horn from below, photo by Alfred A. Hart, courtesy Department of Special Collections/Stanford University Libraries

Cape Horn

Among the early challenges was Cape Horn, about 3 railroad miles east of Colfax. The blueprint as plotted out by Judah and confirmed by Montague called for workers to sculpt the side of a mountain more than 1,000 feet above the American River, which wound its way through the canyon below.

A train travels along the scenic Cape Horn section of track, 1,400 feet above the American River

While legends that Chinese fashioned wicker baskets from which they were suspended while carrying out the blasting of the granitic hill are likely exaggerated, there is no doubt that the heavy lifting of carrying the granitic shards gave the workers a preview of the back-breaking work they would encounter as they made their way east gaining nearly a mile in elevation.

Cape Horn remains one of the more picturesque spots on the line, with the American River threading the canyon below and the peaks protruding into the horizon.

At this point, everyone involved with the Central Pacific realized the pace through the Sierra would be painstaking. Despite the favorable grade of the range’s west slope, the going was slow. It took a full year to lay track from Colfax to Dutch Flat, about 12 miles, with more than 50 miles remaining to build.

The team continued to make progress upslope through the end of 1865 until New Year’s Day 1866, when a large storm brought about 5 feet of snow to the mountains, snarling the construction team. Making matters worse, it was one of those winters in the Sierra when dry weather prevailed through January and February, while it snowed through March and April and into May. Another snowstorm struck the Sierra on June 1, 1865, hindering construction plans for the summer even further.

Nevertheless, Strobridge, Crocker and the workers managed to reach Cisco in November 1866.

Tunnel 6 under construction, photo by Alfred A. Hart, courtesy Department of Special Collections/Stanford University Libraries

Tunnel 6

At the same time, the Central Pacific began the most daunting project of the entire Transcontinental Railroad, which, if completed, would arguably be the single greatest engineering feat of the nineteenth century—Tunnel 6. In order to bring trains over the summit, they first had to go through it.

The east portal of Tunnel 6 and wagon road from Tunnel 7, photo by Alfred A. Hart, courtesy Department of Special Collections/Stanford University Libraries

The plan was to carve out a tunnel 1,659 feet in length—more than a quarter mile—through solid granite and then bring the track down the steep escarpment of the east slope in a meandering route past Donner Lake. When completed, getting the line from Truckee to present-day Reno would prove a cinch, as the line essentially followed the Truckee River and continued into the Nevada desert with its comparatively flat topography.

But Tunnel 6 proved a bear. It was one of 15 tunnels the Central Pacific used to conquer the Sierra and was by far the most difficult.

It took the contributions of thousands of Chinese workers, most of whom were vastly underpaid compared to their white counterparts. It was all done by hand. They worked in teams of three, with one man holding the drill, while the other two workers swung hammers. Once a sufficiently sized hole was augered out, a man would fill it with blasting powder, light a fuse and hope for the best.

Many Chinese died in accidents related to the blasting.

Compounding the difficulty of the work, the winter of 1866-67 was even worse than the previous, which many of the locals said was the worst they had seen.

Summer snow drifts on Donner Summit during construction, photo by Alfred A. Hart, courtesy Department of Special Collections/Stanford University Libraries

The storms came early in 1866 and persisted into the summer months. In all, 44 separate storms crashed into the Sierra that year.

To continue the work, the Chinese laborers had to dig an elaborate network of tunnels through the snow to get to and from the construction site at the summit. The Central Pacific would have called it off and waited out the winter, but the race with the Union Pacific was on and delay was no option.

While several Chinese perished in the blasting—particularly as the crew transitioned from black powder to more effective, but deadlier, nitroglycerine—avalanches also took lives. In one incident an entire 20-man crew of Chinese workers were swept away in an instant, carried into a steep ravine where they died, their bodies unable to be retrieved until the snow melted.

But they kept on. They worked from three separate directions, with crews not only working from both ends of the tunnel, but from the middle.

To make such a thing possible, Clement ordered a vertical shaft bored down into the mountain at the midpoint of the tunnel so that crews could use it as a launching point toward each end. The crews advanced at a pace of roughly 14 inches per day.

Camp near Tunnel 6, photo by Alfred A. Hart, courtesy Department of Special Collections/Stanford University Libraries

In August 1867, the crews advancing toward one another finally met. Their encounter in the middle of a granitic mountain provided proof that the engineering calculations of Clement were surprisingly accurate—the facings were only 2 inches off, a feat that could hardly be replicated today with the benefit of modern instrumentation. The tunnels had to be 19 feet high and 16 feet wide at the bottom.

The degree to which the tunnel was a marvel of engineering cannot be overstated. It was the largest ever attempted, and at 7,000 above sea level sat perched higher than any train had ever reached.

The tunnel itself dropped 30 feet in elevation and curved slightly in the middle.

While the Union Pacific needed to get trains over the Rocky Mountains, specifically at Sherman Pass, through the Black Hills of Wyoming and over the Wasatch Range in Utah, nothing matched the sheer imaginative audacity and eventual sense of accomplishment of boring a quarter-mile tunnel through granite without the use of any equipment aside from hand drills, hammers, black powder and nitroglycerin.

Tunnel 6 was the crowning achievement of the Central Pacific Railroad. Despite the heavy loss of life, the railroad workers emerged triumphant.

Lower Cascade Bridge above Cisco, photo by Alfred A. Hart, courtesy Department of Special Collections/Stanford University Libraries

Railroad Over the Mountains

In 1868, using land granted by the government, Crocker founded the city of Reno, naming it after a Union general who died at the Battle of South Mountain.

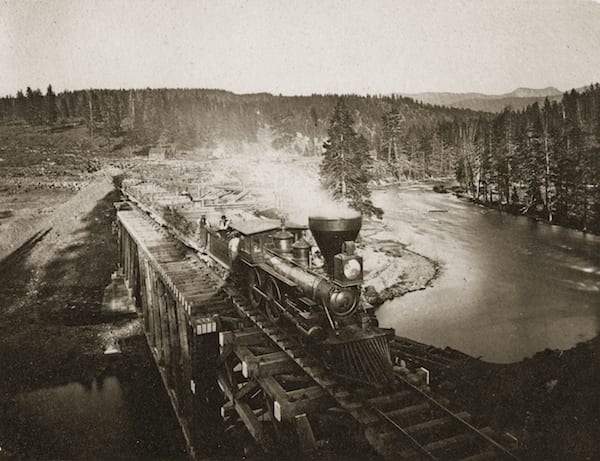

A locomotive crosses the Little Truckee River near Boca, photo by Alfred A. Hart, courtesy Department of Special Collections/Stanford University Libraries

Crocker put the land around his hastily constructed train station up for sale and business was brisk almost immediately, with speculators and shopkeepers rushing to scoop up property due to the lure of proximity to the railroad.

Truckee, too, benefited from a train station built there in 1867, as the area evolved from a remote mountain stopover with a store or two into the bustling mountain town it has remained ever since.

The Central Pacific laid track from Truckee to Reno in May 1868. A month later, crews laid track at the last remaining gap between Cisco and the summit, meaning the Central Pacific and its multitude of workers had prevailed in forging a ribbon of iron rails that traversed the mountains.

On June 18, 1868, the Central Pacific sent its first train from Sacramento to Reno, a feat that few thought possible less than a decade earlier.

Less than a year later, on May 10, 1869, the Central Pacific met the Union Pacific in Promontory, Utah.

The Nevada desert was not without challenges. But Strobridge’s crew got so efficient at laying track, they occasionally gained as much as 3 miles per day, and in one day set a record by creating 10 miles of track.

Back at Promontory

Back at Promontory

Hence the celebrations waxed boisterous on May 10. At Promontory, the engineers laid long on the shrill whistles and it was followed by whoops and hollers by the workers, mostly Irish and Chinese, who had made it possible with their grit and determination.

But Anna Judah, back in Greenfield, Massachusetts, shut herself indoors that day, refusing to see visitors, instead thinking of her husband Theodore—the man who dreamed the First Continental Railroad into existence.

The railroad line—dubbed “Uncle Sam’s waist belt” by writers of the day—was the first railroad to span a continent in the world. It was completed a decade before the Canadian Pacific Railway and nearly 40 years prior to Russia completing its version.

Judah was right that it unlocked the economic might of California and the American West, but he probably underestimated the degree to which the connection from sea to shining sea would transform the young nation into the economic powerhouse of the twentieth century and beyond.

What used to take months of arduous travel now took significantly less time, while the journey was made in comparative comfort. A person could swim in the Atlantic and dip into the Pacific a week later.

“I hear the locomotives rushing and roaring, and the shrill steam-whistle, I hear the echoes reverberate through the grandest scenery in the world,” Whitman wrote in his homage to the First Transcontinental Railroad. “I see the clear waters of Lake Tahoe, I see forests of majestic pines.”

Whitman’s vision was made possible by Judah’s. It wasn’t only his dream; he put in the hard work when there were more doubters than not. His accomplishment is further bolstered by the fact that Interstate 80, surveyed in the 1950s with modern equipment and the use of helicopters, mostly hews closely to his line.

Construction at Sailor’s Spur, 80 miles from Sacramento, photo by Alfred A. Hart, courtesy Department of Special Collections/Stanford University Libraries

Today, the Union Pacific no longer runs through Tunnel 6. As a result, adventurous hikers can walk the quarter mile themselves to get a closer look at one of the world’s most impressive engineering achievements.

Union Pacific, which still runs the transcontinental line, has since dug another tunnel. It’s 10,000 feet long and bores directly through Mount Judah, named in honor of the fabled engineer and visionary.

Some suggest that fact is ironic, while others find it altogether fitting.

Matthew Renda is a Santa Cruz–based writer and former Tahoe resident who has tripped around the Donner Summit tunnels on many occasions.

Michael Cecconi

Posted at 10:24h, 29 Mayvery well down thete is loads of info on the history on this subject I have 5 books on this route and retired as an locomotive is on this route in 2018 of November . Awesome job!!!