02 Dec Stranded in the Sierra

Though the Donner Party bears George Donner’s name, a man named James Reed was responsible for many of the group’s bad decisions—and its eventual rescue

In Truckee, there’s no escaping the legacy of the infamous Donner Party, the group of 80-plus emigrants stranded while trying to cross the Sierra Nevada in the crushing winter of 1846-47. Even after more than 170 years, the Donner Party’s suffering continues to fascinate, namely because, desperate to survive, many of the group resorted to cannibalism. A February 1847 article in the California Star detailed the fates of a small band who’d escaped the mountains, relating, “the weaker began to die which rendered it unnecessary to take life, and as they died the company went into camp and made meat of the dead bodies of their companions.” After describing the horrors, the writer later, almost gleefully, continues, “I have not had the satisfaction of seeing anyone of the party that has arrived; but when I do, I will get more of the particulars and send them to you.”

Cannibalism is perhaps why popular books are being written about the Donner Party almost two centuries later, to include Ethan Rarick’s 2008 Desperate Passage and Michael Wallis’ 2017 The Best Land Under Heaven. But cannibalism is only a portion of the Donner Party’s tale. Their misadventures were truly a series of bad decisions, bad timing and bad luck. And while it would be easy to blame George Donner, acknowledged as the group’s leader, much of the responsibility for the group’s predicament—as well as their eventual rescue—lies instead with a man named James Reed.

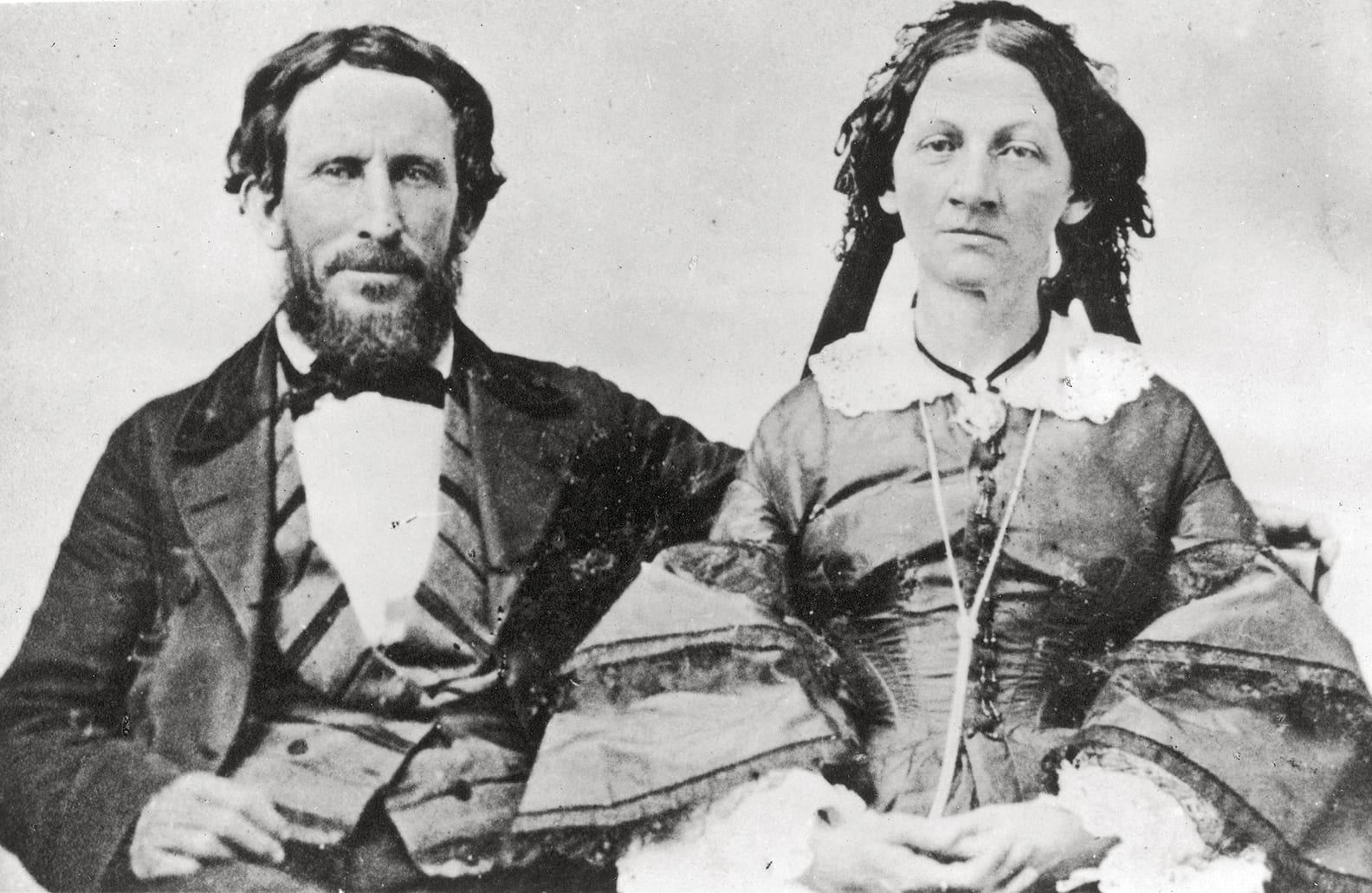

James Frazier Reed and Margret Keyes Reed, photo courtesy Utah State Historical Society

James Frazier Reed and Margret Keyes Reed, photo courtesy Utah State Historical Society

True Leader

Reed was rumored to be an arrogant man. Self-made, he found success in Idaho, though part of the allure of moving west for Reed may have been to avoid debtors. He traveled with his wife, Margret, her 12-year-old daughter Virginia from a previous marriage, and the couple’s three children, Patty, James Jr. and Thomas, ages 8 to 3, as well as Margret’s mother.

In 1891, four decades after the famed Sierra Nevada crossing, Virginia Reed (then Virginia Reed Murphy) wrote about her family’s travels in The Century magazine. “Our wagons, or the ‘Reed wagons,’ as they were called, were all made to order and I can say without fear of contradiction that nothing like our family wagon ever started across the plains. It was what might be called a two-story wagon or ‘Pioneer palace car.’”

The Reeds left Idaho with an additional two wagons filled with provisions and several teamsters, and traveled with George Donner, his wife Tamzene and their five children, plus Donner’s brother, his wife and their seven children.

It was only about two weeks into the journey that Reed’s mother-in-law died. The emigrants stopped to hold funeral rites, a luxury they would not be able to afford later as the death toll mounted.

Overall, though, the trip started smoothly. The Reeds and Donners traveled at the end of a caravan of almost 500 other wagons traveling to Oregon or California. Food was plentiful. One day, Reed went hunting for buffalo and brought back fresh meat. He noted in his journal that he was hailed as “the acknowledged hero of the day.” Another day, Daniel Boone’s grandson shared buffalo meat with the group.

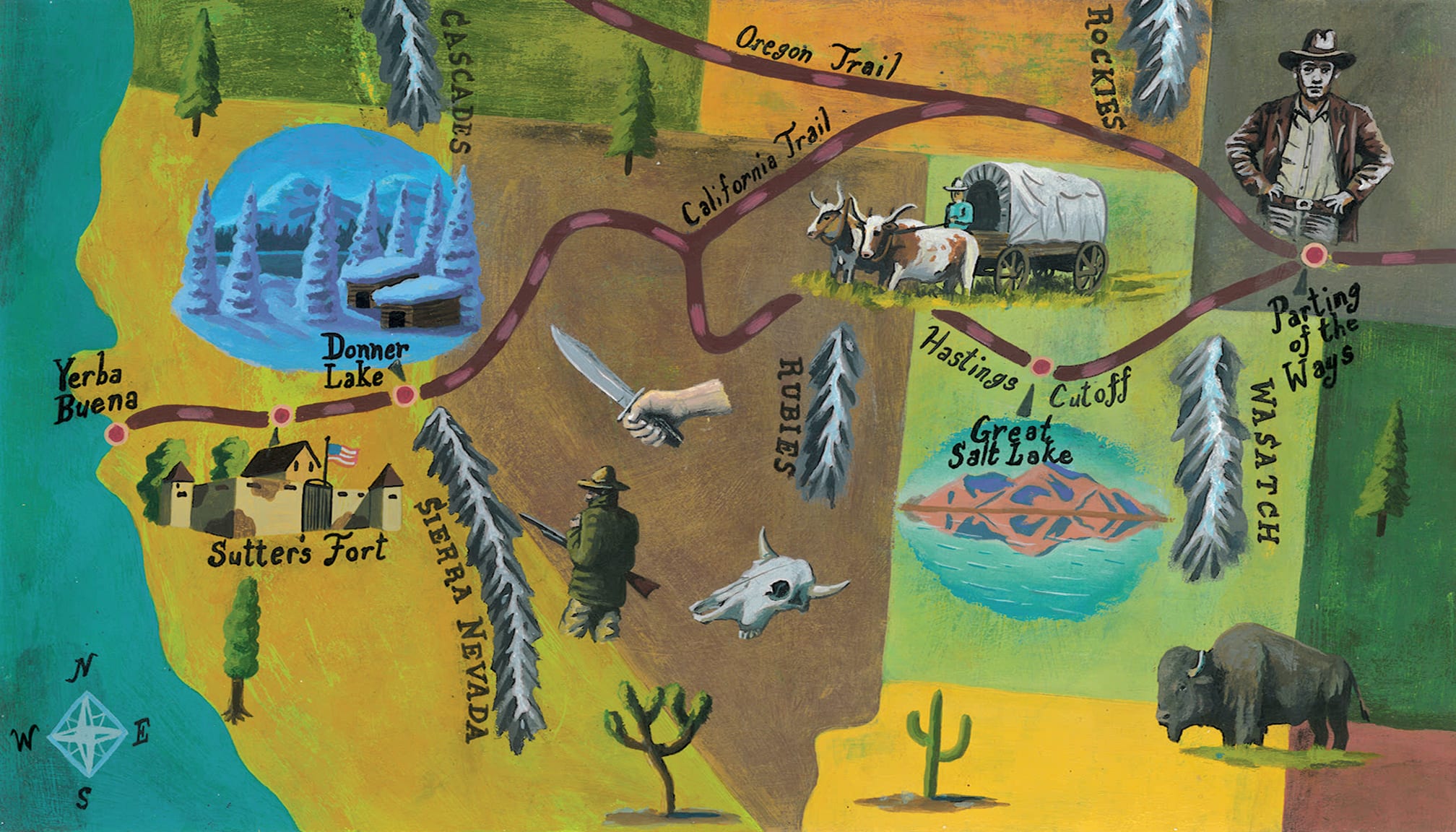

Hastings Cutoff

The typical trail for California veered far north, but Reed discovered a more direct route in a book, The Emigrants’ Guide to Oregon and California, written by Lansford Hastings. Hastings promoted a “shortcut” that crossed the desert by Utah’s Great Salt Lake, rather than going up through Idaho.

Hastings, however, had never taken the route he espoused. A lawyer in his late 20s, Hastings wanted to promote emigration to California, and figured the direct route would bring in travelers that may otherwise be redirected toward Oregon.

In 1846, as Reed pondered which path to take, Hastings was in California. He decided to take his own trail, the so-called Hastings Cutoff, backward, then convince emigrants on the main trail to take it through Utah. Among those joining Hastings was James Clyman, an explorer who doubted the cutoff’s feasibility. Clyman’s fears were confirmed when he saw the Great Salt Lake Desert; he wrote in his journal that it was the most “desolate country perhaps on the whole globe,” adding that no vegetation or animal could exist.

When Hastings reached the main trail to await emigrants, Clyman continued down the path, passing many wagon trains until he, by chance, ran into an old friend: James Reed.

Reed and Clyman had served together in the Black Hawk War 14 years earlier (along with another friend, Abraham Lincoln). Reed questioned Clyman about the Hastings Cutoff, which Clyman advised against. When Reed argued that the cut-off was more direct, Clyman again warned him, saying the trail may be impassable.

It wasn’t the answer Reed wanted to hear. And when he learned a few weeks later that Hastings himself would wait for wagons and personally guide them, his mind was made up, and he convinced the Donners and the rest of the party that they’d save time on the cutoff.

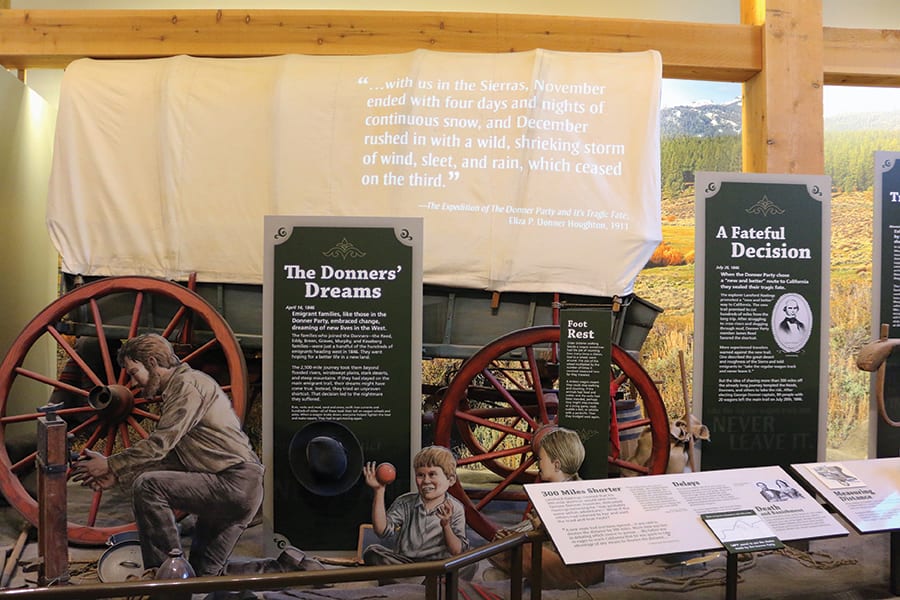

A scene depicting the Donner Party’s fateful journey on display at the Donner Memorial State Museum in Truckee, photo by Sylas Wright

Bad Decisions

Just past Wyoming’s Continental Divide, the wagons reached a place known as the Parting of the Ways. Most took the established path to the northwest. Reed, the Donners and a few dozen others headed southwest. The travelers chose George Donner as their leader, a point that most likely rankled Reed, as he didn’t mention it in his journal. Ethan Rarick, in Desperate Passage, writes that Donner was “a friendly fellow with enthusiasm and goodwill… Maybe Donner was a little malleable, but better that than a self-important blowhard like Reed.”

The Donner Party saw no sight of Hastings, who was then leading the Harlan-Young Party through the grueling elements of the Weber Canyon near the Wasatch Mountains. But Hastings had left a note telling the party to send a messenger ahead and Hastings would return. Reed, with two other men, left to find their elusive guide.

They found Hastings across the Wasatch. Hastings agreed to return immediately with Reed while the other men rested. Yet, Reed and Hastings only made it a little distance before Hastings backed out, saying he needed to return to the Harlan-Young Party. He gave Reed vague directions and disappeared again. “For the rest of their journey,” Rarick writes, “the members of the Donner Party would never again speak with the man who had promised to lead them.”

Reed returned to the party. He’d deemed the canyon trail too difficult, and instead marked a Native American trail on his way back. The party’s options were limited: backtrack, try the canyon or take Reed’s new path. In Reed’s journal, he wrote that his account of the paths “induced” the company to proceed with his route. The decision to cross the Wasatch would take the group more than two precious weeks. It was late August and they still had to cross the Sierra.

Bad Luck

The majority of the travelers were families with children. Beyond the Reeds and the Donners, the wagons mostly comprised families: the Breens, the Murphys, the Eddys and Kesebergs, as well as the teamsters who worked for them. As the group crossed the Wasatch, one final group of wagons rolled up with the Graves family, completing the group recognized as the Donner Party.

After the challenge of the Wasatch Mountains came the Great Salt Lake Desert. In her later account, Virginia wrote, “Worn with travel and greatly discouraged we reached the shore of the Great Salt Lake. It had taken an entire month, instead of a week, and our cattle were not fit to cross the desert.”

One man died and oxen and wagons suffered through the bogs. Again, James Reed rode ahead, hoping to find drinkable water, then returned to hurry his children to water before they all died of dehydration. Teamsters unyoked animals, allowing them to reach water. Finally across, the group rested about a week as they searched for missing animals and brought back left-behind wagons. The gamble was costly: Not only did the Donner Party lose time, but they lost 36 cattle in total. George Donner and Lewis Keseberg each abandoned a wagon; the Reeds abandoned two of their three wagons, including the “Pioneer palace car.” It placed the Reeds in an uncomfortable situation, reducing their fortunes and forcing them to rely on help from the other families.

They continued across the Ruby Mountains and into what is today Nevada, following the Humboldt River. They’d lost precious time and precious supplies. Unsurprisingly, tensions rose.

The Pioneer Monument at Donner Memorial State Park, the Jon B. Lovelace Collection of California Photographs in Carol M. Highsmith’s America Project, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

On October 5, John Snyder, who worked for the Graves family, tried taking a wagon up a steep hill without doubling up on oxen, as the other teams did. He whipped his oxen, trying to urge them upward, but one of Reed’s teamsters interfered. Reed entered the argument and Snyder struck Reed in the head with the butt end of his ox whip; Reed retaliated by fatally stabbing Snyder in the chest with a hunting knife.

Reed immediately regretted the blow. He offered boards from his last wagon to make a coffin.

“At the funeral my father stood sorrowfully by until the last clod was placed upon the grave,” Virginia wrote in her 1891 account. “He and John Snyder had been good friends, and no one could have regretted the taking of that young life more than my father.”

George Donner, as the leader, should have been consulted on what action to take, but his wagons were two days up the road. Instead, the remaining party members hashed it out among themselves. Keseberg (who didn’t like Reed, as Reed had remonstrated Keseberg for beating his wife) supposedly wanted Reed hanged, but the rest decided on banishment. Reed was forced out, leaving his wife and children behind. “Now,” Rarick writes, “short on both provisions and time and still hundreds of miles from its destination, the Donner Party would have to push ahead without its one true leader.”

Reed took only one teamster, Walter Herron. They had one horse and took turns riding, but food quickly grew scarce. At one point, as they crossed the mountains, they noticed one bean on the road, a relic from a previous traveler. Reed later wrote, “Never was a road examined more closely for several miles.” They found five beans in total and nearly died on that lonely stretch of trail.

Amazingly, the travelers found a group of emigrants, including a man who had left the Donner Party weeks earlier and was now returning with help and supplies. They fed Reed and Herron, who continued westward and eventually reached Sutter’s Fort, near what is now Sacramento.

Bad Timing

The rest of the party continued to hit setbacks. Native Americans stole oxen, horses and cattle. There were more deaths, including one man in a firearms mishap. And, worst of all, heavy snow hit the upper peaks of the Sierra in late October, unseasonably early.

On October 31, about two-thirds of the group had reached what was then Truckee Lake. Unable to cross the mountains, they waited, but a few days later, a heavy storm began and it snowed for the next eight days.

“Despair drove many nearly frantic,” Virginia recalled. “Each family tried to cross the mountains but found it impossible.”

Reed, on the other side of the Sierra, tried to return to his family, but he encountered the same impenetrable snow.

Resigned to wait, those at the lake built cabins and utilized one that already existed. Thanks to a broken wagon axle, the Donners themselves were 7 miles behind the main group. They put together rough shelters near Alder Creek; strangely, none of the adult Donners stayed at the lake that today bears their name.

After more than a month of captivity, in mid-December 1846, after several failed escapes, one team, nicknamed the Forlorn Hope, managed to break free. They’d rationed food for six days; the journey took a month. Of the 17 who left, two turned back and eight died on the crossing. Some of the dead were then eaten.

Reed worried about his family, but not knowing about the stolen animals, he believed they had enough meat to last a couple of months. Since it was impossible for him to return, he joined a war mission, fighting in a skirmish known as the Battle of Santa Clara in January 1847. He also went to San Jose, where he submitted land claims, forging signatures from his wife and two of his trapped employees. With business done, he was ready to try again to save his family.

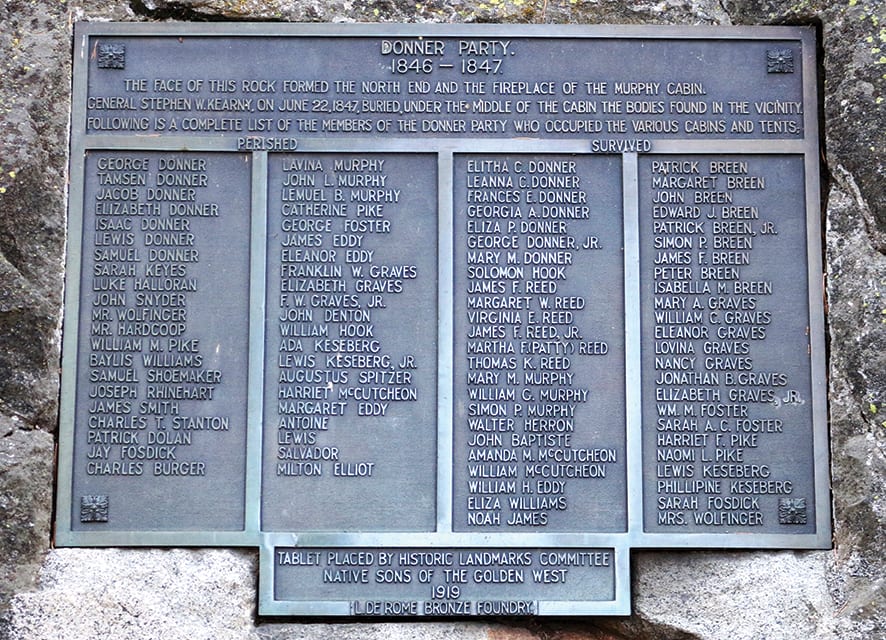

A memorial plaque marks the rock that formed the north end and fireplace of a cabin built by members of the Donner Party, photo by Sylas Wright

Breaking Free

In the Sierra, people were desperate.

“The misery endured during those four months at Donner Lake in our little dark cabins under the snow would fill pages and make the coldest heart ache,” Virginia later wrote.

Snowbound, those at Donner Lake made meals out of cattle hides and other things normally considered inedible. As people succumbed to starvation and cold, some of the survivors turned to eating the dead.

In February, a small band of rescuers reached the camps and organized a group to leave. Margret Reed gathered her four children, but it was soon apparent that two of them, 8-year-old Patty and 3-year-old Thomas, couldn’t continue. One rescuer offered to take them back to the camps, and though it distressed Margret to break up her family, she had to help Virginia and James Jr. to safety.

In the meantime, Reed had put together his own rescue mission. He’d traveled to Yerba Buena, as San Francisco was still known, and met with local leaders and townspeople at a hotel saloon. Reed was said to be so overcome with emotion he was unable to speak; instead a minister told of the group’s plight. Donations came in instantly—more than $1,000—and following that success, Reed continued north, fundraising and finding men and horses. On February 23, Reed again returned up the mountain. The snow was too much for the animals, so the men shouldered the packs and continued on foot.

A few days into the trip, scouts informed Reed that his family was on the way. Too excited to sleep, Reed spent the night getting ready for them. “My father was hurrying over the mountains, and met us in our hour of need with his hands full of bread,” Virginia later remembered. “He had expected to meet us on this day, and had stayed up all night baking bread to give us.”

Though exuberant to see his wife and two children, the reunion was cut short when Reed realized two more children were still stranded. The rescuers continued, through snow they estimated at 30 feet deep, until they arrived at camp, Reed joyful to find Patty and Tommy still alive.

The rescuers gathered 17 people, many children, from both Donner Lake and the Alder Creek camps, and again attempted to break free.

Photo by Sylas Wright

Three days after leaving the lake, it began to snow again, an intense, heavy snow that Reed referred to as a “hurricane.” They hunkered down in an area that became known as Starved Camp, just over Donner Summit, where they were trapped two days; between the cold and lack of food, several people, including Reed, almost died. When the storm finally passed, Reed insisted that they continue, but only three people—his children and a 15-year-old—went with him; the rest were in no condition to travel, and so they remained at Starved Camp for another five days—as people died and were eaten—until help arrived.

Ultimately, it took four rescue attempts to free everyone from the Sierra Nevada’s snowy grasp. Of the 81 people originally trapped in Truckee, only 45 survived, at least half of whom were children. Besides the Breens, the Reeds were the only family to survive intact, and they were said to be the only ones who did not partake in cannibalism.

As for the Donners, all the adults died. Tamzene likely would have survived, but her husband was on his deathbed and she refused to leave him, even though it meant separating from her children. By the fourth rescue mission, she was dead, though whether it was the elements or by the hand of Lewis Keseberg, the last remaining survivor at the camp, is lost to history.

After the ordeal in the Sierra, life improved immensely for the Reed family: Reed served briefly as the sheriff of Sonoma, then settled in San Jose where he owned land. And though the Reed name is not prominent in Truckee—like the Donners—in San Jose, streets named Reed, Margaret, Virginia, Keyes (Margret’s maiden name) and Martha (for Patty) still exist.

Newspapers at the time sensationalized the Donner Party story, exaggerating facts and painting the group as barbaric, rather than victims and survivors. Some of the party tried to distance themselves from their pasts, but others, including Virginia Reed, later wrote their own accounts. Several of Virginia’s letters survived, as well, including one that she wrote in May 1847, at age 13, to a cousin in Illinois not long after her escape from the mountain.

The letter detailed the group’s troubles, but also the relief in their survival. Despite their hardships, Virginia didn’t want to “dishearten” her cousin, or anyone else who might want to travel west. With hard-earned wisdom, she wrote, “Never take no cutof[f]s and hurry along as fast as you can.” It’s sage advice that would have served her father well.

For more on the Donner Party, Alison Bender recommends Ethan Rarick’s Desperate Passage and Michael Wallis’ The Best Land Under Heaven.

No Comments