30 Nov An Extreme Journey

How the talented athletes and iconic mountains of Tahoe helped push the boundaries of skiing and snowboarding to new heights

Tahoe has played a pivotal role in the world of winter sports several times in recent history: the 1960 Winter Olympic Games and, in the 1980s, the creation of the snowboard halfpipe and the birth of the “extreme skiing” phenomenon.

My intersection with extreme skiing was entirely accidental. I was a kid from the coast who had fallen in love with Tahoe. In the 1970s, it also seemed the right spot to start a freelance career. So by coincidence, that career got rolling at the same moment as did extreme skiing.

Setting the Stage: Daydreams to Hot Dog

Ski, boot and binding technology improved at a rapid pace from the 1960s into the ’70s, allowing the best skiers to push the envelope of the previously possible. The exploits of some are preserved in the cult ski film classic Daydreams, filmed and produced in winter 1974-75 by North Tahoe resident Craig Beck. A jaw-dropping moment features Craig’s brother, Greg, launching 100 feet from the top of the Palisades cliff band, his landing briefly knocking him out cold. Despite stunning cinematography, the self-funded film only played to limited audiences. But it did throw a spotlight on Olympic Valley as a place to test the outer limits of one’s skills, and nerves.

At the time, North Tahoe was home to multiple extreme legends in the making. Rick Sylvester had pioneered BASE jumping by skiing off Yosemite Valley’s El Capitan with a parachute in 1972. He made his forever-mark in the film world by doubling for Roger Moore’s James Bond in 1977’s The Spy Who Loved Me, skiing off a 6,000-foot cliff on Mount Asgard, free-falling until popping open a Union Jack parachute.

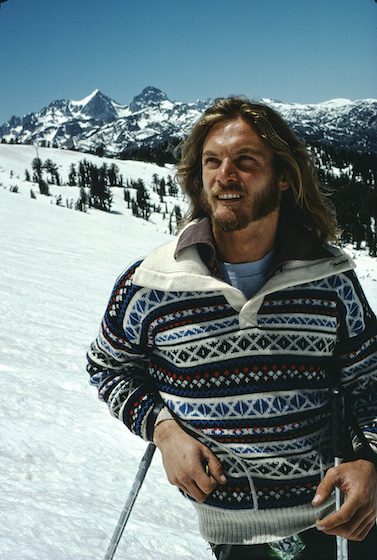

Steve McKinney was a pioneer of speed skiing, becoming the first person to exceed 125 miles per hour, photo by Eric Perlman

At the pinnacle of Olympic Valley skiers during this era was Steve McKinney, a promising young downhill racer who rebelled against U.S. Ski Team constrictions, traveling to Italy in 1974 and setting a new speed skiing world record. Four years later, McKinney became the first skier to go over 200 kilometers per hour (125 miles per hour)—labeled the “impossible barrier” by the European ski press—while reportedly tripping on LSD. Extreme? Yep.

In 1982, I wrangled an article assignment from Powder magazine on our local speed skiing heroes and spent an evening in a single-wide in the Tahoe City Trailer Park (now 64 Acres Lakeside Park) with McKinney, Paul Buschmann, Tom Simons and, visiting from Austria, Franz Weber—each of whom would win World Speed Skiing Championships at least once. Days later, I met McKinney to get some photos and we headed up the KT-22 chairlift to the steep moguls of West Face (later renamed Moseley’s Run for Olympic gold medalist Jonny Moseley).

“Do you like bump skiing?” McKinney asked.

“Sure,” I answered, somewhat confidently, since I was a regular on Scott Chute at Alpine Meadows.

“Let’s go,” he said, and pushed off straight down the fall line, gaining speed almost instantly while jumping from the top of one mogul to another. I watched with dropped jaw as he arced into wide super G turns, fully in flight at 30-plus miles per hour, bending his knees to impact the top of each mogul perfectly with micro-second carves. He rocketed down the entire 1,000 vertical feet in maybe six big turns. It remains one of the most extreme feats on skis I’ve ever witnessed. To Steve McKinney, it was ho-hum. He waited as I made my way down the steep hill, one mogul at a time.

As John Walsh, Olympic Valley native and U.S. Ski Team veteran, states: “Many radical ski lines (at Palisades Tahoe) documented in the Squallywood book (authored by Robb Gaffney) were first skied by Steve McKinney, Craig Calonica and other locals well before the extreme era.”

Before he was tragically killed by a drunk driver in 1990, McKinney left his mark on the speed skiing world in multiple ways, forming the first athlete-run sanctioning organization and expanding the race circuit from one event in Italy to competitions in Chile and Silverton, Colorado, later hosting citizen speed skiing events at numerous U.S. resorts. Seeking the farthest reaches of human experience, he also joined and led ski expeditions to Denali and the Himalayas, flying a hang-glider at 22,000 feet off Mount Everest.

Birth of ‘Extreme’

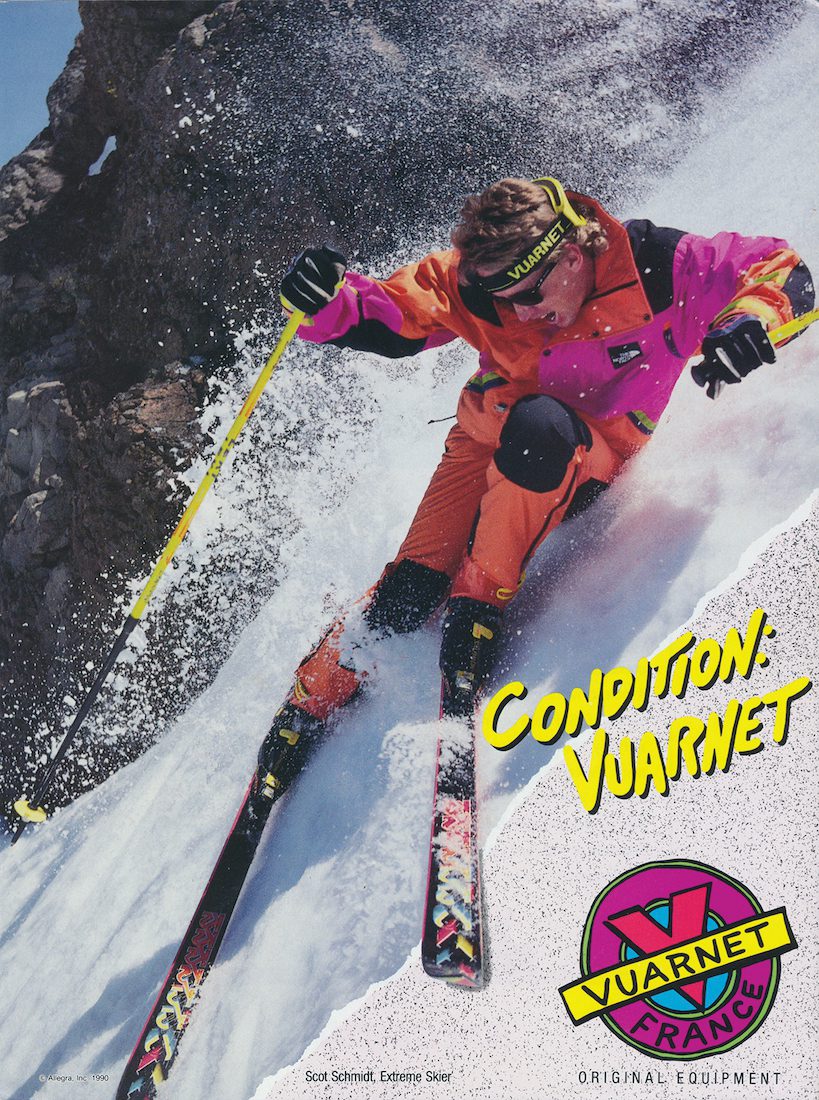

The fall and winter of 1983-84 were pivotal to the defining of extreme skiing. North Tahoe resident Scot Schmidt appeared in his first Warren Miller film, Ski Time, and the classic ski party flick, Hot Dog … The Movie!, was released, produced by Olympic Valley local Mike Marvin.

Tahoe and Hollywood B talent combined in the silly but outrageously fun Hot Dog. Amazingly, some of the scenes were accurate to real life Tahoe in the 1970s (as anyone who hung out in Olympic Valley’s Bear Pen can attest). Marvin’s signature creation was the climactic “Chinese Downhill” race segment, with dozens of skiers taking off from the top of the mountain at the same time, featuring multiple high-speed crashes and Truckee’s Robbie Huntoon skiing through High Camp lodge at the top of the tram and crashing back out to the snow through a window.

It’s hard to exaggerate the power of Warren Miller’s voice in American skiing in the 1970s and ’80s, with many thousands lining up at theaters from coast to coast as an autumn ritual, looking to get pumped up for skiing. So in 1983, when Miller’s soaring narrative introduced the nation to Schmidt in Ski Time as an “extreme skier,” a shift in ski culture occurred, although we could not recognize it at the time.

I had heard he was an incredible skier from my fellow photog, Larry Prosor, but I met Schmidt when I was just past being an Alpine liftie and he was washing dishes at River Ranch. So my general reaction to Miller’s “they call it extreme skiing” in Ski Time and subsequent films was, “Huh?” Wasn’t Schmidt just pushing the envelope slightly past what top experts did every day on the toughest ski mountains? But as was often the case, Miller’s instincts were prophetical. His well-chosen words and Schmidt’s elegant skiing gave the world a soon-to-be universal name for superior daring-do and performance. And like many in the ski business, I would soon be drinking the “extreme” Kool-Aid.

In the fall of that year, Powder assigned me the first national profile on Schmidt, to be accompanied by Prosor’s epic photos. The article included Schmidt’s clarification that “real” extreme skiing was the death-defying ski mountaineering descents of European alpinists like Patrick Vallencant and Sylvain Saudan, with the article adding a plea for U.S. ski resorts to open more expert terrain.

Rob DesLauriers launches off a Palisades Tahoe cliff in a North Face Extreme Team shoot, photo by Eric Perlman

The spotlight on Schmidt and Olympic Valley attracted new elite athletes to the area, among them two sets of brothers, Dan and John Egan and Rob and Eric DesLauriers. They and a who’s who of top freeskiers would become part of The North Face clothing’s “Extreme Team,” led by filmmaker/cinematographer Eric Perlman of Truckee, with a revolving cast of still-photogs invited on shoots.

The 1988 season saw the release of perhaps the purest expression of the era’s zeitgeist—Blizzard of Aahhh’s by Greg Stump—a film credited with “popularizing the concept of extreme skiing” (CNN) and introducing the world to Tahoe’s most iconic extreme star, Glen Plake. Son of South Lake Tahoe’s fire chief, Plake was a competitive mogul skier with a talent for big air and (it would turn out) big hair.

“He was frustrated by the competitive scene,” his lifelong friend, Darren Johnson, told me once. “Then one morning, he called me and said, ‘I got it! It’s all about the mohawk.’”

Stump’s seminal film tells the story of how Plake busted his way into the Palisades shoot and became, along with Schmidt and K-2 telemarker Mike Hattrup, the film’s star. Fast-forward 34 years and his extreme career rolls on, his druggie days well in the past with a sober Glen Plake one of skiing’s most lighthearted, popular spokespersons.

Miller’s movies kept riding the extreme wave, too, and in fall 1989 I headed south from South America for his 1990 film Extreme Winter, shooting stills of Tahoe locals Kevin Andrews, Tom Day and others on the “first extreme ski expedition to Antarctica.” We flew by Twin Otter with ski landing gear onto the glaciers of the mountainous Antarctic Peninsula. Trapped by a big storm for days, our tents were anchored in the wind by huge frozen sausages we had dug into the ice, which we’d have to dig up and eat if the days stretched into weeks. The storm broke and we climbed and flew to two “first descents.” I wrote a piece on the journey for Skiing magazine and National Geographic TV edited their own show from cinematographer Bill Heath’s footage.

Movie fame and equipment company sponsorships were now all flowing toward the new extreme athletes, and some winter sports competitors weren’t so happy about it.

“There was jealousy directed at ski film stars, and later the extreme competitors,” remembers U.S. Ski Team standout Kim Reichhelm. “Ski racers had worked so hard and put so much of ourselves into the sport. And then someone comes along with nowhere near the technical skills and is getting all the attention.”

“Posers” was the term I heard from top racers at the time when dismissing the new extreme stars. Ski photographers like myself were looking for posers, of course. My experience photographing both top racers and the new extreme skiers was that the latter had mastered two skills many racers hadn’t: hitting an exact spot or line in peak action, time after time, and skiing imagination lines down dangerous terrain with nary a scratch, time after time.

Turning the Extreme Into Sport

As the 1980s became the ’90s, posing was all that extreme skiing and snowboarding consisted of, defined exclusively by movies and magazine pages. Up in Alaska, however, a young man who was looking to attract more visitors to his mountain lodge on Thompson Pass figured out a way to turn it into a sport.

Michael Cozad and his girlfriend, Shannon Loveland, convinced the town of Valdez and, more importantly, Alyeska Pipeline Service Company to sponsor the first World Extreme Skiing Championships in 1991, the template for all freeski and freeride competitions to follow. Soon top skiers across the country received invites to attend. Skiing flew me up to shoot the contest and I shuttled to Valdez with judges Perlman, Schmidt, Plake and Hattrup, all of them, as I recall, skeptical that Cozad could validate his crazy idea.

The inaugural World Extreme Skiing Championships gathered the icons of the day—Scot Schmidt, Glen Plake and Mike Hattrup—to help establish judging criteria that is still used today, and to sign posters for local kids and media, photo by Chaco Mohler

At the first meeting of competitors and judges in Valdez, Cozad proposed a set of judging criteria but asked the group for their feedback.

“The categories we decided on are still the ones used in today’s freeski competitions,” says Reichhelm, who received one of Cozad’s invitations.

The first day of competition, we were shuttled by helicopter to the top of “27-Mile” run and I skied and crampon-ed my way with two or three other photographers onto a 45-degree-plus slope, a chocolate-chip snow and rock minefield ending in a big cliff. I don’t remember that any competitor or media on the mountain that day was wearing a helmet.

Forerunners and early competitors stayed to a safer adjacent couloir. Then a relative unknown from Jackson Hole, Doug Coombs, flashed precise turns down the most exposed line below us and took a hard right above the cliff and into the couloir. The bar had been set.

Kevin Andrews, the most solid of skiers, headed into the chocolate-chip slope yelling, “F**k, f**k!,” before every turn, then exiting safely into the couloir.

“After the first day of competition,” remembers Reichhelm, “most everyone had had our minds changed. The experience was completely liberating. I had more fun than I ever had skiing in my entire life. My eyes were opened.”

Coombs won the men’s division and Reichhelm took home the first of her many extreme contest wins.

“I went back to Crested Butte after the first Worlds and told the resort, ‘I just went to the coolest ski event ever and we have to do one here.’”

The next year, 1992, Crested Butte, Colorado, hosted the first U.S. Extreme Championships, a string the resort has kept going through the decades. During summer 1994, two contests were launched in the Southern Hemisphere: South America and New Zealand championships. Freeride snowboard contests also debuted, with Nick Perata creating the seminal King of the Hill competition in Alaska in 1994.

Like Reichhelm, I came back from the first Worlds in Valdez completely jazzed. My enthusiasm grew as I went back to subsequent Valdez and Crested Butte contests. I started to think about how this new sport could be showcased on television. In 1994, that interest led me to join a partnership with Mark Phillips and Patrick McIntyre to organize the first extreme ski and snowboard competitions on the West Coast at what is now Palisades Tahoe.

I met with resort co-founder and owner Alex Cushing and his wife Nancy Wendt Cushing three times before they signed off on hosting this somewhat unproven concept. The “All-Mountain Extremes” was held March 20–26, 1995, the first extreme contest to include ski, snowboard and combined divisions, with McIntyre organizing on-mountain venue and judging.

More than 3 feet of fresh powder and sunshine blessed our Finals Day held on Granite Chief peak, producing both fine technical turns and an epic huck fest. Kings Beach’s Chuck Patterson won the Combined, sticking matching 70-footers on skis and a snowboard (with windshield wipers duct taped as a brace on a knee he had tweaked earlier in the contest). Kristen Kremer, reigning New Zealand Extreme Ski Champion, flew 120 feet off the nose of Granite Chief and outjumped all the men. Female snowboarder Morgan Lafonte executed a perfect 60-foot backflip and landing.

“Having the Finals on Granite Chief Peak was insane,” says Patterson. “There hasn’t been a contest since that has been able to do that. It was just an awesome event.” (Patterson has gone on to a multi-sport extreme career, now known as much for his big-wave surfing and kiteboarding championships as his ski and snowboard skills.)

Extreme Goes Mainstream

We aired a one-hour All Mountain Extremes show in major U.S. markets that next fall and winter, 1995-96, on Sports Channel (the precursor to Fox Sports). The next season, Phillips and I formed a new production company, Element X, and organized the first extreme contest at Kirkwood, while McIntyre organized one more event in Olympic Valley.

Kirkwood Resort’s then-president, Tim Cohee, was an enthusiastic supporter of the contest and the television. But we wanted to hold the Finals in The Cirque: an ideal spectator venue of cliff-laden terrain, “permanently closed” to skiers throughout the resort’s history. Kirkwood Ski Patrol wanted nothing to do with our idea. So Cohee sent me out with patrol leader Dave Meyers to ski it. My two pitches to him were: Preliminary days of the contest, held on safer terrain, weed out pretenders, and, “You can’t believe the skill of the top athletes.” Meyers eventually gave us permission, on a short lease, and we held the first Kirkwood extreme contest in March 1996, with the Finals in The Cirque featuring epic skiing and riding and no major injuries.

Distributors for a beverage company launching in the U.S., Red Bull, supplied us with cases of product (but no money) for the event. So, when we goofed up on Finals Day and ran out of water for the judges and crowd in the sunny finish area, all there was to drink were cases of Red Bull. Judges, spectators, competitors … everyone was soon chugging multiple cans of this then-unknown beverage like it was water, producing a buzz in most that bordered on extreme.

Sports Channel aired an hour show nationwide on the Kirkwood contest starting in fall 1996. The following winter, Phillips and I organized the first U.S. series, the “Big Mountain Extreme Tour,” creating the first extreme contests held at Jackson Hole, Wyoming, and Bridger Bowl, Montana.

Tahoe legend Shane McConkey in the early days of Alaskan heli-skiing, photo by Chaco Mohler

During this same period, I had an ongoing conversation with Olympic Valley’s Shane McConkey, who (along with Reichhelm and other top skiers and filmmakers) had judged at our contests. Like many skiers before him, McConkey felt strongly that the word “extreme” was not appropriate to the spirit of the events. I saw his point, of course, but any sponsorship we had managed to procure had been undeniably attracted by the extreme phenomenon launched by Miller and catapulted by Stump.

“Shane was very passionate about calling the contests ‘freeski’ instead of ‘extreme,’” remembers Reichhelm. “I saw his point—he was a purist—but from a marketing perspective, extreme was definitely preferable. It explains the sport better than freeski.”

Although McConkey tragically left us years later in a BASE jumping accident, he, like McKinney, transcended his super-athlete persona to literally change his sport, pioneering the creation of “fat” powder skis and leaving a lighthearted legacy that lives on through the charity work of Sherry McConkey, his soulmate and partner.

“What we were doing was extreme as it gets,” remembers Chris “Uncle E” Ernst, organizer of the seminal “Lord of the Boards” competition at Homewood Resort in 1996, an event that featured the first skier-cross event in a combined ski, telemark and snowboard format. “But in those years, we were all disgusted by the way the word ‘extreme’ was being used to sell toothpaste or whatever.” (Ernst has gone on to a successful TV career that includes color commentating for multiple X Games.)

McConkey and other top athletes also gave feedback to ESPN-TV, which was planning to launch a new “Extreme Games.” The network reportedly changed it to the “Gen-X Games” after hearing from the competitors. ESPN aired its first winter contest, televised live, in 1997 at Snow Summit resort in Southern California. In subsequent winters, ESPN moved the event to Crested Butte and then Aspen, shortening its title to the X Games along the way.

In the months following our third Kirkwood contest, McConkey and other top athletes formed the International Freeskiers Association with plans to sanction further events. During the same weeks, we were in discussion with a television network on a series of “World Tour” contest shows. That deal fell apart when we couldn’t find a European resort that would host an extreme event (where now large annual contests are popular).

As we contemplated running another winter of contests, Phillips and I were suffering enthusiasm-deficit. It felt time to move on to new challenges. We handed the Kirkwood contest over to the resort and through the years they and IFSA members have continue to produce world-class freeski events in The Cirque.

Other than Kirkwood, big-mountain contests disappeared from Tahoe’s resorts for many winters. Luckily, that has all changed. Youth big-mountain teams and competitions in the Tahoe Junior Freeride Series are now an exciting presence at many Tahoe ski areas.

My 20-year journey through the extreme ski world was, of course, an extremely exciting period of my life, and certainly the riskiest. Now, a quarter century on, I’m acutely aware of what a privilege it was to explore spectacular mountain ranges and hang out with fascinating people and uber-athletes, some of whom are tragically gone, and others who remain treasured friends.

Chaco Mohler is the former publisher of Tahoe Quarterly and the magazine’s first editor-in-chief.

No Comments