02 May Riding the Lens

Tahoe’s pioneering snowboard photographers captured iconic images that helped shape the sport

Shaun Palmer at Donner Ski Ranch in 1985, photo by Bud Fawcett

Bud Fawcett remembers when it clicked. Just days before the 1985 Sierra Cup, a snowboarding event, a storm dumped 4 feet of snow on the Tahoe Basin. The highways shut down. Almost everything came to a standstill. Except the lifts. Fawcett, a budding snowboard photographer, and pro riders Terry Kidwell, Shaun Palmer and Tom Sims showed up at Donner Ski Ranch to take some runs.

“There was nobody there, but the chairs were running,” Fawcett remembers. “It was the first day that I had ever snowboarded in powder top to bottom without falling. I was hooked at that point. I really had a great time.”

Not only had the sport forever ratcheted into his veins, but he got a glimmer of the future that capturing it on film might afford.

“I shot three photos that day and all of them were published,” Fawcett recalls.

Fawcett would go on to be one of the preeminent snowboard photographers of the mid-1980s and early ’90s. He, along with a cohort of skateboard-inspired Tahoe shooters, would capture the sport’s raw teenage years and the explosive growth that followed.

Photography from Fawcett, Sean Sullivan, Aaron Sedway and Chris Carnel—much of it focused on the Tahoe scene— graced magazine covers, defined brands, inspired a huge cohort of younger photographers and adorned the bedroom walls of snowboarding’s biggest fans around the world.

“There’s a depth of pioneers and culture and influences that came out of here,” says Pat Bridges, former editor of Snowboarder Magazine and founder of Slush Magazine, who now lives in Incline Village. “And the reason why they’re all pioneers, cultural icons and influences was the photos. First and foremost, the photos, and then later on the videos came to back it up as well.”

Tom Sims at the World Snowboarding Championships at Soda Springs in 1985, photo by Bud Fawcett

The Early Days

Of all the photographers who trained their lenses on snowboarding’s trailblazers, Fawcett’s entry was perhaps the most unlikely.

Born in North Carolina, Fawcett enrolled in his high school’s yearbook class and newspaper as a photographer. The only problem: He’d never actually taken a photo. After borrowing a camera, he dove into photography with the zeal of a teenager, learning to shoot and develop film. His first photos were published while working for the school newspaper at the University of North Carolina.

A few years later, after a long road trip and a handful of odd jobs, he found himself sitting for a job interview as inventory manager at Sims Skateboards in Santa Barbara.

“I didn’t even know what a skateboard was,” Fawcett says. “I’d never seen one living in North Carolina.”

Tom Sims, founder of Sims Skateboards, would go on to become a founding father of snowboarding and build his company into one of the sport’s iconic brands. As Fawcett worked in the warehouse, he noticed snowboards began showing up. Sims’ employee at the time, Chuck Barfoot, another soon-to-be snowboarding legend, had started to design prototypes for the company. The problem was the boards weren’t selling—yet.

“Things got really slow, and I told [Tom Sims], ‘You know what, Tom? Snowboarding is going nowhere. I don’t know why you’re wasting your time,’” Fawcett says with a laugh. “I swear I did say that to him.”

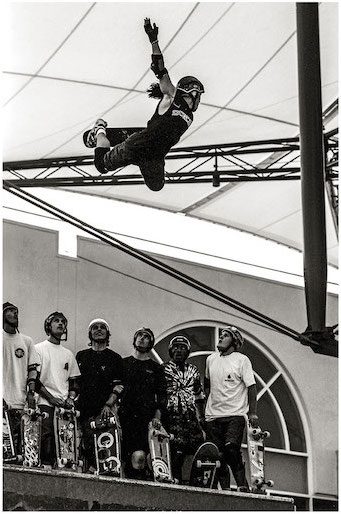

Christian Hosoi airs above some heavy hitters of the pro skate world, including Steve Steadham and Jeff Grosso, among others, at the Long Beach Trade Show, circa 1989, photo by Sean Sullivan

For Sullivan, Sedway and Carnel, skateboarding was just a part of childhood.

Both Sullivan and Sedway grew up in Southern California while some of the biggest names in skating like Christian Hosoi and the Dogtown crew were rolling around the streets and hunting for rippable backyard pools. Sullivan found photography after an injury took him out of skating. He saw it as a way to keep up with his friends. Sedway first took a photo class in high school, but failed when he couldn’t secure a camera. His mom eventually helped him out.

“I just got obsessed with photography along with snowboarding and skateboarding at the time,” Sedway says. As with Sullivan, Sedway’s early skateboarding images were published in Thrasher Magazine.

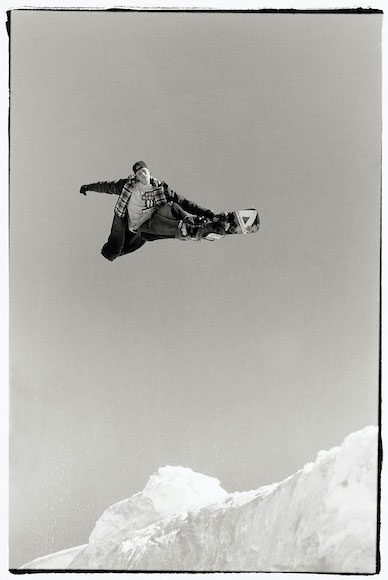

Carnel was raised in Reno, where he started documenting a burgeoning scene of ramps and street skating from a young age. Many of his skate friends made their way to the mountains in the winter. Carnel liked to bring his camera during those early trips to Mount Rose. He remembers shooting with pros like John Cardiel, who would go on to become one of the world’s elite skateboarding talents.

“Starting out, I was really into it,” Carnel says. “I started to get photos that I liked. I just kind of went with the flow and just kept shooting.”

Not long after Fawcett started capturing snowboarding regularly, Carnel ran into him at Mount Rose while Fawcett was shooting with South Lake Tahoe pro Shaun Palmer. They became friends, with Fawcett often sharing his wisdom.

“He would do slideshows and talk about lenses and gear,” Carnel recalls. “It was cool to geek out. There wasn’t an online community, so it was just kind of knowing people and experimenting.”

A Tool for Progress

As Fawcett settled in Tahoe, eventually becoming staff photographer at the Tahoe World, snowboarding was transitioning from its infancy of hand-built halfpipes and poaching to being legitimized on the runs of some of the region’s largest resorts.

Terry Kidwell with an iconic capture at the Donner Quarterpipe in 1986, photo by Bud Fawcett

In 1986, Fawcett captured one of his most iconic images: Tahoe-born-and-raised legend Terry Kidwell tweaking a double-handed rocket air out of a natural quarterpipe feature across the street from Sugar Bowl. The frame, Fawcett says, helped him become noticed by publishers.

It also stood out because it showed progression: riders getting serious air and doing it with style.

“Really, photography was a tool for progressing the sport,” Bridges says. “Whether it was style or tricks or hitting cliffs or slashing turns, it’s cliché to say, but you don’t know what can be done until you see it done. If somebody’s not shooting it, how would a kid in Vermont, like myself, know what they’re doing in Tahoe?”

Sullivan landed in Tahoe in 1989. He dove into shooting, making regular appearances on Donner Summit and pointing his lens at pros like Noah Salasnek, Chris Roach and Steve Graham, among others. He soon met Mike and Dave Hatchett of Standard Films fame, who were both at the heart of Tahoe’s snowboard community, and, at one point, rented a room from the brothers. He started shooting photos during video shoots for Fall Line Films, one of the first snowboard-focused production companies. He also learned from Fawcett.

“He helped me figure out how to get the exposures dialed,” Sullivan says.

Sedway followed a similar path, eventually signing on to shoot photos on trips with Standard Films.

“Tahoe was a photographer’s dream,” Sedway says. “It had the terrain to put snowboarding on the map, great weather and fairly easy access.”

By 1990, magazines like Snowboarder and Transworld Snowboarding had become major titles and brands like Sims and Burton started licensing images. Still, photographers had to be scrappy to make a living. Before their photography careers took off, Sedway and Fawcett worked at photo labs in the area in their spare time.

Tracy Latzen, Donner Summit, mid-’90s. “Tracy was one of the most stylish riders I ever shot with,” says photographer Sean Sullivan, “and this image really captures that,” photo by Sean Sullivan

Developing Style

As snowboarding grew, a variety of interests influenced the sport. From hard boots to gate-bashing races, skiing’s impact was widely felt. Riders who skateboarded (or were inspired by skateboarding) brought their own feel to the snow with technique, grabs and style.

“The sport was very much in flux back then,” Sullivan says. “There was this sort of tug-of-war going on between the ski industry and the skate world for the soul of snowboarding.”

The photography conveyed these unrefined roots. Magazine covers at the time ranged from the screaming neon hard-booted airs of famed South Lake Tahoe rider Damian Sanders to the wild tweaked mute grabs and early jibs of esteemed pro Noah Salasnek, who was based on Tahoe’s North Shore. As the culture, tricks and riding evolved, so did the photography.

“Snowboarding just became an extension of skateboarding. [The riders] would bring skateboard tricks to the snow,” says Sedway, who photographed popular pro skateboarders like Steve Alba before getting into snowboarding. “And my photography just followed.”

Sullivan liked to feature techniques and equipment common to skateboard photography: fisheye lenses, flash and an in-your-face composition. His style, though it sometimes seemed out of place among many photographers who were using 50-millimeter and 200-millimeter zoom lenses on the mountain, matched many of the riders who were into skating.

“I had a very skateboarding-centric punk rock ethos that I took over to snowboarding,” Sullivan says. “I had a specific way I thought it should be done. I wanted to see snowboarding emulate skateboarding, and I was vocal about it.”

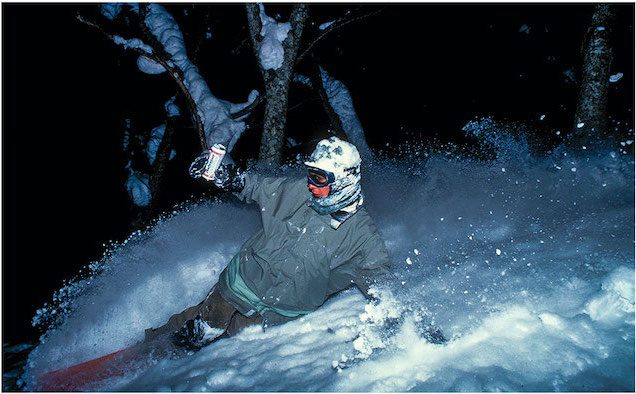

Mike Ranquet night riding with a tall boy in Niseko, Japan, photo by Sean Sullivan

With a density of motivated pro riders, a variety of photogenic and easily accessible spots like Donner Summit, and a growing number of resorts welcoming the new sport, Lake Tahoe became central to the snowboard scene. The region’s stable powder, giant cliffs and big jumps became frequent subjects.

“We’d hop in the car and spend the day driving around Donner Summit,” Sullivan says. ‘We wouldn’t have to drive more than 2 miles and we’d hit 10 things and bag so many killer shots, especially if the snow was good. And the snow was relatively consistent back then. If you had a decent powder day with some sun and you had some solid riders, it really wasn’t that hard to get it done.”

John Cardiel on Donner Summit, 1991, photo by Chris Carnel

‘Tip of the Spear’

Images from Fawcett, Sullivan, Sedway and Carnel began to pepper the magazines, and an unspoken code was woven into snowboard photography. Photos would no longer feature “the guy in the sky,” with no reference to the takeoff point and landing of the rider. This helped the viewer understand what was really happening in the image, Sullivan says. From grabs to deep powder slashes, photos had to capture style.

“A lot of photographers couldn’t figure out what the action was supposed to look like,” Fawcett says.

Their knowledge of skateboarding helped the photographers dial into the peak moments on the snow, but the sport was changing fast. As ski areas opened their lifts, riders continued pushing the boundaries, and the photographers captured it all.

“We were the tip of the spear when it came to content,” Sullivan says. “There was no Instagram, there was no Facebook, YouTube, TikTok, no social media back then. There were the magazines. And the magazines were the voice of the sport.”

For Carnel, the sport’s progression seemed natural and he didn’t think too much about its growth. He was there to shoot.

“It’s just one of those things,” he says. “It’s like the beginning or genesis of something. You don’t really realize it or know what the impact is, but it’s inspiring and you’re just there documenting it and checking it out. It’s a cool thing.”

Despite all the pressures pulling the sport in different directions, snowboarding came into its own. No photographer could ignore the early morning mountain light and the beauty of cold smoke powder rooster-tailing from the back of a ripping rider. For good photography, you needed a Venn diagram of talent, cold, powder and sun, Sullivan says.

“If you have all four of those lines cross in one place, you’re going to have a great day,” Sullivan says. “Tahoe was one of the places where you were most likely and would have the easiest time bringing all four of those forces together compared to just about anywhere else in the world.”

Jeremy Jones rides Grizzly Spines in the Sierra backcountry for Standard Films’ 2006 movie Paradox, photo by Aaron Sedway

The Momentum

The realities of being a photographer at the turn of the 1990s were wildly different without the conveniences of digital imaging and wireless Internet. Shooting film required lightning reflexes and a solid sense of anticipation. Motor drives were becoming more common, but they still weren’t ubiquitous.

“You had to know when to push the button. It wasn’t at the moment when the action happened. You had to be just a second before,” Fawcett says. “I tried to be at the moment all the time by shooting just one picture. The photo editors used to just laugh at me. They’d ask, ‘How many photos did it take to get this?’”

Then, there was the developing. Fawcett would often shoot a roll of his favorite color Kodachrome film and not know what was on it for weeks after sending it in to Kodak. Carnel, who still often shoots with film, remembers that feeling of uncertainty.

“You just didn’t know,” he says. “That was part of the process that was kind of cool. You just had to rely on experience and hope that your film didn’t get botched in a lab or scratched or anything. It was kind of crazy.”

They’d send their slides to the magazines, but often wouldn’t know what was published until they started flipping through new issues. But the sport kept growing, and Tahoe was right at the center of it. Fawcett remembers going to what is now Palisades Tahoe to shoot snowboarders coming down under the resort’s sign.

“There was 40 people in the photo and people just kept coming down the mountain—then there was 80 people,” he says. “People were waiting for [the resort to open to snowboarding]. That was the moment.”

The momentum continued for Fawcett. He shot for years with many of the sport’s biggest names, including Damian Sanders, Terry Kidwell and the late Craig Kelly. He had a brief stint as the photo editor at International Snowboard Magazine. In an accident that left his left arm paralyzed, Fawcett was hit by a snowboarder on a blind jump in 1992. He continued to shoot occasionally, eventually learning Photoshop and becoming a creative director. Fawcett is widely considered the first successful full-time snowboard photographer. He now lives near Portland, Oregon.

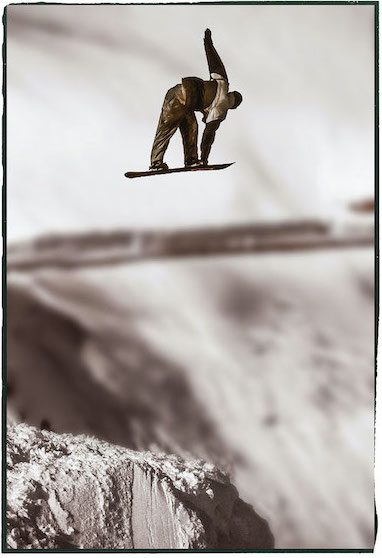

Noah Salasnek drops into Super Spines near Haines, Alaska, for Standard Films’ 1995 classic Totally Board 5, photo by Aaron Sedway

Carnel, Sullivan and Sedway became senior photographers for Snowboarder Magazine, traveling around the world to capture the sport’s progression. Sullivan remembers shooting with Norwegian snowboarding icon Terje Håkonsen.

“He redefined the notion of what it meant to be a gifted snowboarder,” Sullivan says. “There were a few guys like him. Craig Kelly was another guy that every single time he hits a jump, you’re going to get a shot.”

Sullivan lives near Auburn in the Sierra foothills and still shoots, now primarily focusing on sport fishing. He’s published multiple hardcover books of his photography, including Lines, a compilation of his snowboarding images.

Carnel photographed the early jib scene and made international trips with many of the top pros. He became a founding partner of Heckler Magazine. Carnel still lives in Reno and continues to photograph, often showing his work in the region.

On trips to Alaska with Standard Films, Sedway showed the world the next level of big-mountain riding, including Salasnek’s famous first descent of Super Spines for the 1995 Standard Films classic Totally Board 5.

“I just always had my camera,” says Sedway, who lives in Reno and still shoots, now combining his photography with painting to create surreal abstracts (he also works with Mike Hatchett as a commercial and residential house painter). “It was just part of my routine back then. I didn’t think much of it at the time. I just wanted to be out snowboarding with my friends, but I’m honored to look back now and see that I was part of Tahoe’s early snowboarding roots.”

Dylan Silver is a freelance writer and photographer based in the Sierra. He’s the author of the underwater photography book Clarity: A Photographic Dive Into Lake Tahoe’s Remarkable Water. A former intern at Snowboarder Magazine, Silver’s love of snowboarding extends back to his first lesson at 8 years old on a snowy day at Kirkwood.

No Comments