27 Jun Chair Apparent

Robert Erickson has built a life on handcrafting museum-quality furniture—a business he now shares with his son, Tor

Van Muyden Chairs. The three-legged chairs are constructed of Pacific madrone and fiddleback bigleaf maple

Before Robert Erickson’s handmade furniture caught the eye of national collectors, before his three-legged Van Muyden chair joined the Yale University Art Gallery collection, before his fiddleback maple rocking chair was added to the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Nevada City-area craftsman tried his hand at a very different line of wood-related work: Christmas tree sales.

Robert is known around the country today for the way he honors his raw materials and borrows forms from the surrounding environment. Decades of design and labor have yielded a collection marked by details that hint at naturalistic elements—a desk set with legs almost like curved horns, a chair with joinery that flows like a branching antler, a table with a shape reminiscent of a hide stretched to tan.

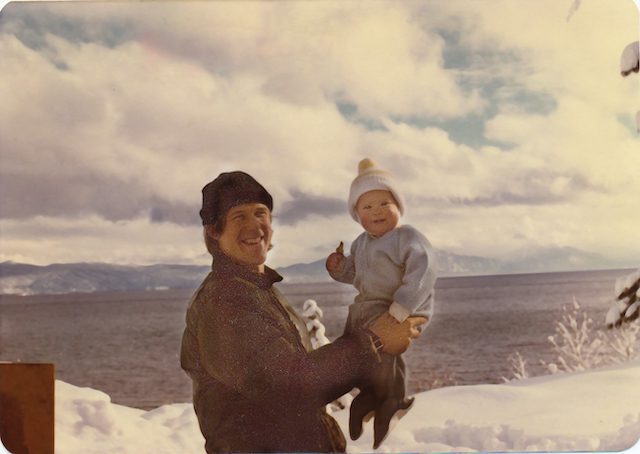

But in December 1979, Robert, his wife Liese Greensfelder and a business partner set up a lot near the Watson log cabin in Tahoe City. Their goal? To sell about 350 salvaged white firs he had downed earlier that year as part of a thinning contract with the U.S. Forest Service. Crammed into an 11-foot trailer with his family—including his 9-month-old son, Tor—Robert burned the sawed-off green butt ends of the trees for heat and used the bathrooms at nearby businesses to conserve water.

A young Tor Erickson with his mom, Liese Greensfelder, at Lake Tahoe in 1979

They sold just 26 trees in four days while living a life of what Robert called “effluence amidst affluence,” watching scant buyers trickle in and haggle over heights and prices. Business remained slow for weeks. Then, on December 21, several feet of snow brought a wave of skiers and tourists eager to spruce up their holiday with some greenery. The neighboring lots quickly sold out, prompting panic in procrastinating families facing a holiday with nothing to preside over their presents.

“We were the only people who had any trees left,” Robert says. “In the last three days, we made more money than we ever had before.”

After their successful sales run, a Christmas storm buried them in their trailer and knocked power out around the lake. Digging out through a wall of snow, they discovered that their propane lantern was the only light they could see for miles—apart from the full moon.

Robert Erickson holds up his 9-month-old son, Tor, at the family’s Christmas tree lot in Tahoe City in 1979

More than four decades later, an amber glow still tints the memory of the holiday for Robert, now 76. He tells the story upon some prompting from Tor, now 44. Though Tor moved away for about 10 years in his 20s—studying, traveling and working—he’s since returned to what he considers a very special place to do very meaningful work. The two men now share a workshop, much brighter, airier and roomier than the trailer where Tor spent a month of the first year of his life. Their mutual pride in their work, in each other, is obvious: It hangs in the air like sawdust and swirls between them as they move from station to station.

“Bob’s lucky,” says Dr. Julian Fisher, a Boston-area neurosurgeon, art collector and outspoken proponent of the Ericksons’ work. He notes that Robert and Tor’s ongoing partnership, with Tor returning to develop innovations of his own and push furniture marketing in a way Robert hadn’t before, is rare in the industry: “So many craftspeople do what they do, and their kids go off and become bankers, brokers and crooks.”

Shaping a Life

Robert’s ancestors came from central Sweden in the 1870s to homestead in central Nebraska. A few generations later, after he graduated from the university there in 1969, he “evaded the draft” and headed west himself, seeking to “learn actual real skills.”

Chief among those skills was woodworking. He attributes his initial curiosity in the endeavor to “some Foxfire books by a guy in Appalachia documenting handcrafts made by old hillbillies.” Such skills seemed to be on the decline, he felt, as design trends and preferred materials were changing across the country.

“One of the people he documented was a chairmaker,” Robert says, “and the image of busting a chair from a tree was very powerful in my imagination.”

Salvaging a large incense cedar log that was used to build the Erickson home in Nevada City in 1976, three years before Tor was born. From left: Bob Greensfelder, Dick Sisto, a young Jeremy Sisto (before becoming a successful actor), Robert Erickson, Jonathan Keehn and Bob Bellezza

He was romanced by the notion of cutting down an oak or an ash, splitting it into parts, and then putting it together into something new. He quickly realized the various pieces of a chair may have come from different kinds of trees, each chosen because of the wood’s unique characteristics.

Buoyed by that idea, he eventually hitchhiked all the way out to San Francisco, where he met poet and real-life Dharma Bum Gary Snyder, who invited him to travel northeast and help build a log house based on earth lodge structures from the Great Plains and Japanese country temples.

After months of work in the Sierra foothills, Robert and some of the others who collaborated on the project decided to buy the property next door. He built a woodshop that doubled as his residence in 1973 and got married in 1978. Tor was born in 1979.

“We’re still here,” he says. “The core of that group is still together on a shared piece of land under what’s called a ‘limited equity co-op.’”

A solar array provides power to the property, backed up by a battery system that has evolved over the years. He now has a proper home separate from the workshop, too. Robert and Tor use a solar kiln for seasoning the wood they collect—often walnut from Woodland, Davis and Sacramento—and their workshop is surrounded by various storage structures and piles of planks.

Erickson Woodworking, from left: Robert Erickson, Liese Greensfelder, Tor Erickson and Bobby Corns

The land is also dotted with cameras, which Robert and Liese use to spot the wild creatures who share the property, from mountain lions to bears. Robert maintains a fascination with his plant and animal neighbors—noting when he hears spotted owls seeking a mate outside his bedroom window or sees the first orange-crowned warblers coming in before they head to Tahoe—with the interest bleeding into and informing his profession, as well.

“I would like to say that one of the things that has really interested me about woodworking—but also regional woodworking, and by that I mean digging deep into using local materials that come from the landscape—[is that] the more we’ve used the materials, the more we’ve learned about not only those specific woods, but where they come from, how they grow, what are the insects that eat them,” Robert says. “That kind of regional reflection of the landscape you live in has always kind of been a philosophical, spiritual base for me.”

Shaping a Business

Aside from his foray into Christmas tree sales at the tail end of the 1970s, Robert has built his furniture business on the foundation of intimacy with the environment and those who transform it for decades.

Erickson Woodworking’s Columnar Table with South Yuba Chairs, combining California walnut, basalt stone and bronze

“When I started, I thought I was the only person in the world who ever thought of making handmade furniture,” Robert says.

He soon realized, however, that there were thousands of others with the same idea—enough to start something of a social movement.

“My dad was kind of the second generation of this revival of the American crafts movement through the twentieth century,” Tor says. “This was a movement where there was this renewed interest in building things by hand—and I think a response to other trends happening around the country. … The idea was that it wasn’t something to hang on a wall; it was a wooden bowl meant to be used. The belief was that if you had an object in your house that was not just beautiful, but that was made by hand, maybe connected to the person who made it—quotidian, had use in daily life, you put salad in it—that doing this could actually make your life richer and more meaningful.”

Robert admits to taking some inspiration from others in the movement—such as George Nakashima, who pioneered the “live edge” look on tables to evoke a relationship to the original form of the tree—but he prefers to respectfully work in general traditions as opposed to copying other styles.

Among his personal innovations is the “floating back” rocking chair, which he devised in the 1970s as a pinnacle of form meeting function. Vertical slats gently press against the sitter’s back, bowing and flexing with each movement and adjustment. The effect is almost supernatural, like an alchemist discovered a way to transmute the feeling of walnut branches moving in the wind into an object you can park on a rug in the corner of your living room.

Robert began taking his unique creations on the road to indoor craft furniture shows in the ’70s and ’80s. His travels spanned the coasts, from San Francisco to Philadelphia and Baltimore.

Shaping a Legacy

Fisher has been collecting American crafts since the 1980s, when a year of work in Peru opened his eyes to the wonders that can be made when talented and practiced hands lovingly meet local wood. Upon his return to the Boston area, he began seeking out similar artisans so he could surround himself with functional beauty.

“I realized at that point craft furniture commissioned from artists whose work was in major museums was cheaper than buying furniture at Bloomingdales,” he says. “And far more interesting.”

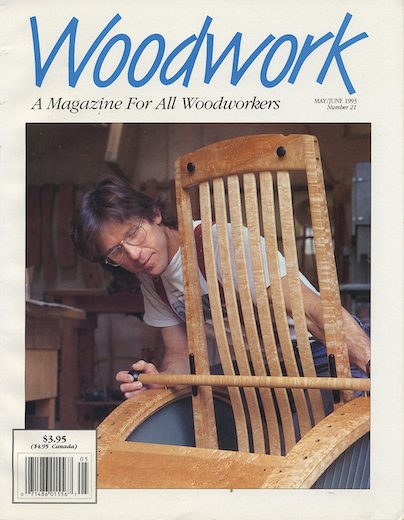

Robert Erickson on the cover of Woodwork Magazine in 1993

He began to furnish his life with turned wood bowls, contemporary quilts and larger pieces, seeking objects he wanted to surround himself with and use regularly in addition to admiring. In the midst of this ongoing hunt, he met Robert in 1981 or ’82 at an American Craft Council Show (“probably in West Springfield”), after which he deliberated over whether to buy a rocker or not.

“I went back another year and thought about it: Did I need it?” Fisher says. “The subsequent year, I thought, ‘Yes. I’m buying it.’ … The ergonomics of his chairs and the ergonomics of his furniture, it just fits. It fits you, your lifestyle, your body, and it looks wonderful and it really honors nature because of the wood he chooses and how well he cares for it and works it up. … He really glorifies the wood.”

Sometime later, Fisher found himself looking to do something in his parents’ memory while helping the Yale University Art Gallery update its collection featuring post-nineteenth century American craftwork.

“Yale began to commission one-of-a-kind pieces from various furniture makers,” Fisher says. “The first was Bob.”

He calls the floating back rocker an iconic design, with work reflecting the woods of the West, built by someone he felt was unrecognized at the time. In those pre-Internet days, it was especially challenging for solo crafters to build an audience. Even today, it’s difficult.

“It’s a tough life as a fine craftsman in furniture because it’s long work, long hours and a tough sell,” Fisher says. “Furniture craftspeople really have to sell themselves, and it’s through craft shows or through the web or connections through designers, and that’s it. They’ve made that commitment over years and taken furniture by truck all over the country to exhibit it at craft fairs and so on, and they’ve made a life for their family. Bob’s made a name for himself, quietly. He’s a very humble person.”

Shaping a Year

Robert still relies on craft shows, though he’s been attending mostly outdoor events in the mountainous West since the late 2000s. Another change? Tor is now an active part of the endeavor. Still, the work hasn’t changed much. Tor describes the summer routine: setting up a booth like a mini house, starting with a floor, trusses and lights. They put down carpet and hang pictures on the walls. They set out the furniture. Then they break it all down, pack it all up and move on.

“We’re sort of carnies in that sense,” Tor says, “moving around, setting up shop.”

Erickson Woodworking’s booth display on the road

Their travels take them into the fall, when they settle back at home as the orders roll in. Winter is devoted to hunkering down and filling those orders. It’s also the time to “get away from the distractions of having to get out there and hustle,” Tor explains. “It’s a good time to slow down, reflect and design then—always designing for clients specifically.”

In the spring, life gets busy again as they finish filling orders from the prior year and start preparing to head out for another summer of shows.

“That cycle—truck, van, booth—that’s been going on for decades. It becomes a feedback loop: build, conceive, go out, show to people, see how they respond, sit in it, sit at tables, learn what works, what doesn’t, what you like,” Tor says. “It’s sort of like a spiral that moves outward.”

Tor’s description of a year in the life of Erickson Woodworking mimics—perhaps unconsciously—the growth of a tree, expanding outward in rings, each new layer reflecting the highs and lows of the year. In fact, the cycle is harmonious with the natural world as a whole: a dormant winter giving way to the preparations of spring, then a summer of activity slowing to an autumn marked by the culmination of growing things bearing fruit. And then it starts again.

“Generally, we do 50 to 75 pieces a year: tables, chairs, everything,” Robert says. “I’m making less furniture, taking more time off.”

Tor cuts in: “He’s actually not really making that much less furniture.”

Shaping a Chair

The Ericksons use ponderosa or sugar pine for their chair prototypes, building each design a few times to work out the bugs, then literally burning the various prior iterations.

The real deal is made with more valuable wood—say, native California black oak or walnut or Pacific maple and maybe manzanita for the details. For much of the wood they use, they mill the logs and bring the wood back to the shop, where it air dries and spends a year or two in a 117-degree solar kiln.

The Sandhill Chair pairs a bigleaf maple burl with forged steel by Mike Route

Rockers are customized for each client. The Ericksons will request measurements, such as upper and lower body height, to ensure the chair fits the way a chair built for a specific buyer should. (“I have a rocking chair that’s mine,” Fisher explains. “It’s for me in more ways than one.”)

Robert admits that some of the best inspirations for new designs come from clients, such as a recent table that needed to fit into a small space while allowing the owners to fold laundry on top. Tor developed a piece of furniture that can be compact or can open up to a large tabletop with storage underneath. Design challenges can lead to surprising conclusions, he explains, with the result being something he couldn’t imagine being built any other way.

“The Platonic ideal of whatever you were designing sort of emerges at the end,” Tor says.

Mostly, though, they stick with their established designs, such as the Wapiti Chair inspired by discarded antlers. This is because an eye-catching design takes work—often years of tinkering. Add to that the fact this art is also functional furniture, which means it needs to meet some intense engineering requirements: A chair must be sturdy enough to support the weight of a person, while remaining light enough to easily be picked up and moved, all while being comfortable to sit in.

“Once you’ve gone through the process of refining all of the form and the shape and the joinery and how it goes together … you have a lot of investment in a piece of furniture,” Tor says. “It really makes sense to, as you come up with a design that really works on all levels, keep that design and move forward. That’s true of all furniture, but especially chairs, which are related directly and intimately to the human body.”

The Silver Chest uses California walnut and California black oak

To that end, one of the last things the Ericksons do before they ship a chair is sit in it. They consider: Is it comfortable? Functional? Aesthetic? Tor says they’re still finding ways to adjust their chairs to make them more comfortable and beautiful—even designs they’ve been making for decades now.

In some ways, this process also mimics nature: The gradual shaping of things by their environment as edges are worn smooth and new surprises occasionally pop up. Given time, anything that brings change to a place—a fallen rock, a downed branch, a shed antler—takes on a new form as it becomes incorporated into the larger world. Soon, it joins its surroundings as an established feature of the landscape, even as it retains some of its distinct characteristics.

This is how a new curve is incorporated into a classic design, a chair is incorporated into a home’s collection of furniture, and how a man seeking something new ultimately has his ideas incorporated into the national consciousness as he is incorporated into a particular western slope of the Sierra Nevada, absorbing the splendor of the region.

“That’s what’s kept me here,” Robert says.

Erickson Woodworking’s furniture will be on display at the Tahoe City Art by the Lake event at Boatworks Mall on August 18, 19 and 20.

Ryan Miller is a writer who lives in the Sacramento area. Follow him on Twitter or Instagram, @jesteram.

No Comments