30 Apr The Trailblazer Who Forged the Flume

Max Jones worked tirelessly throughout the summer of 1983 to create what is arguably the most scenic mountain bike trail in the world. All the while, he was also building a successful career that is still going strong

If trails could talk, the Marlette Flume Trail would fill volumes.

As one of the most historic, popular and scenic trails in the world, the Marlette Flume Trail represents far more than just a tourist attraction. This 4.5-mile-long ribbon of decomposed granite along a benched cliff edge 1,500 feet above Lake Tahoe represents two distinct eras in Lake Tahoe’s history: the early mining days of the Comstock Lode and the eco-tourism movement that drives the modern economy of the region.

But if it weren’t for the efforts of an ambitious young mountain biker named Max Jones, the Marlette Flume Trail might have never been reborn.

Origins of a Famous Trail

From box flume to world-class recreation trail, the Marlette Flume’s existence has spanned more than 150 years, courtesy photo

The Marlette Flume Trail is commonly known as the Flume Trail because, compared to any other flume trail, its breathtaking views of Lake Tahoe and Sand Harbor give it international status as the Flume Trail. There is no other route in the world with such commanding vistas. It truly is a one-of-a-kind experience.

Throughout most of the twentieth century, the Flume Trail was a little-known piece of Comstock Era history that only a few brave hikers with a taste for 22 miles of bushwhacking would ever tackle.

The flume was originally constructed in the late 1800s to deliver potable water 50 miles from Marlette Lake, up and over the Carson Range before dropping 2,000 vertical feet across Washoe Valley, then continuing over the shoulder of Mount Davidson to the silver mines of Virginia City.

Considered one of the greatest feats of human engineering at the time, this remarkable project was completed in only a year. (To this day water still travels from Marlette Lake to Virginia City, though it is now pumped out of the lake rather than transported by flume.)

For decades the flume sat dormant, until the summer of 1983, when Max Jones, then in his mid-20s, walked into a Reno bike shop and discovered a newfangled contraption called a mountain bike. Sporting 18 gears, knobby balloon tires and upright handlebars, it was like nothing Jones had ever seen.

The discovery would set a course for the rest of his life’s adventure, and a career he is still living to this day.

A Time of Discovery

As a fourth-generation Nevadan, Jones comes from a prominent Carson Valley ranching family that emigrated from Minden, Germany, to (ironically) Minden, Nevada, in the 1800s. Jones was the first male in the family to break from the ranching tradition, deciding instead to pursue athletic endeavors as a pioneering rock climber and competitive cross-country skier.

But Jones was looking for a new challenge, and he saw it in the form of a mountain bike.

He began racing and immediately started winning. It wasn’t long before mountain biking legend Tom Ritchey saw Jones in action and offered him a sponsorship with a brand-new mountain bike, handmade by Ritchey himself.

Max Jones with an illustration of Spooner Lake, where he and his wife Patti ran their summer and winter business, photo by Ryan Salm

Jones spent every day on his Ritchey training and exploring the Carson Range, which led to the realization that there were no good singletrack trails for mountain biking. All existing trails were designed for hiking—too steep and tight for a mountain bike to navigate.

He got his hands on a U.S. Geological Survey map and scanned it for any old trails he could ride. A thin blue line on the map above Sand Harbor caught his attention.

“The line said ‘flume,’ and knowing that flumes are usually pretty flat, I wanted to find it and see if it could be a rideable route,” Jones recounts on episode 19 of Mind the Track Podcast.

Because the Flume Trail hadn’t been used in decades, both sides from the north and south were overgrown with brush and fallen trees, making it difficult to find. Jones went to the University of Nevada, Reno, to research everything he could about the trail and its location.

Eventually, he found the trail, and despite the route only being 4.5 miles in length, his first experience “riding” it took him five hours of bushwhacking and climbing over downed trees with his Ritchey in tow.

Despite the bushwhack fiesta, Jones was obsessed with the idea of clearing the trail so he could not only ride it, but also share the unbelievable views of Lake Tahoe with friends.

Building a Legacy

Besides the brush and fallen trees, there was a bigger problem: miles of slippery aluminum pipe in the middle of the trail. After conducting more research, Jones learned that in 1963, a company building a rocket fuel plant in Dayton, Nevada, needed water for its operation. The company laid the aluminum pipe to revive the flume, then ran out of money and abandoned the project, along with the piping.

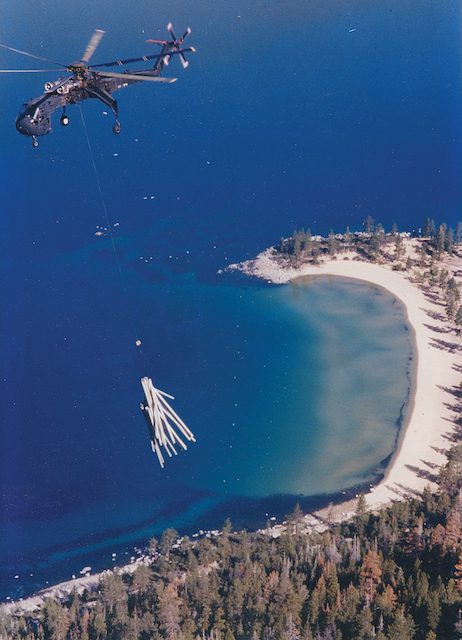

A Nevada National Guard helicopter lifts out miles of old aluminum pipe that Max Jones split by hand with hammer and maul, courtesy photo

Undeterred, Jones hauled a handsaw, loppers, shovel and splitting maul up the mountain on his back, cut out the brush and trees, shoveled out landslide after landslide, and used the maul to split the aluminum pipe into 20-foot sections, rolling them to the side of the trail. Those who’ve ridden the Flume Trail may have noticed the aluminum pipe in the ground, as a few sections remain buried in the trail bed.

Through the summer of 1983, Jones humped his gear on his Ritchey up to the Flume from his Incline Village home, working tirelessly. He thought he was being discrete, but there were eyes on his covert operation.

Mark Kimbrough, park supervisor for Lake Tahoe-Nevada State Park, managed the land above Sand Harbor, which the Flume Trail ran across. Kimbrough noticed someone was doing work on the trail.

“I don’t recall our first encounter, but what I do remember is Max working all summer on clearing the flume, and since it was a pre-existing trail, there was no rule against what he was doing,” says Kimbrough. “I just saw this young man putting in a ton of work to clear the trail, so I figured, ‘Let’s see what he can do.’”

Kimbrough and Jones developed a relationship that summer, with Jones putting in the sweat equity and Kimbrough there to ensure everything was done within State Park guidelines. To remove the aluminum pipe, Kimbrough brought in a Nevada National Guard unit with a Sikorsky helicopter, and with the help of volunteers, they bound the pipe and had it flown out.

“A few years after that my wife Patti and I were cross-country skiing on a trail out near Spooner Lake when we saw an aluminum pipe laying in the woods,” says Jones. “Patti said, ‘Where did that come from? There are no flumes around here.’ That’s when I realized one of the pipes must have fallen from the helicopter.”

As Fate Would Have It

David Zischke rides the Flume Trail in the early days of its existence. Notice the old aluminum pipe and wood along the trail, photo by Larry Prosor

The aluminum pipe represents additional significance: If it weren’t for the pipe’s presence when Jones discovered the route, the Flume Trail may have never become legal for recreation.

Before 1963, the aluminum pipe did not exist on the trail, which still had all the original remnants of the wooden box flume from the Comstock Era. The rocket fuel company came in with machinery and pushed what remained of the box flume off the cliff. Had they left it alone, the materials would be considered artifacts, likely presenting an insurmountable archaeological hurdle for Jones.

Because the damage had already been done, however, Jones was permitted to continue his work, and after a long, backbreaking summer in 1983, the Flume Trail was open for the public to enjoy.

The problem was, not many people were riding mountain bikes yet because the sport was still in its infancy.

“In those first couple years, I’d ride the Flume every day, and my tire tracks were the only ones on the trail,” says Jones.

Because he was a professional mountain bike racer, Jones knew all the biggest names in the sport. So to promote the Flume Trail and get more tire tracks on it, he and his wife Patti organized an event in 1985 called the Great Flume Race.

Putting the Flume on the Map

Named after an event in the 1800s started by two Comstock Era mining magnates—James C. Fair and James Flood, who raced logs down a V-flume off the east side of Mount Rose to Huffaker’s mill pond—the Great Flume Race was an immediate hit with mountain bikers.

This included Tom Ritchey, who brought all his friends in the industry to experience the Flume Trail.

Bob Shelton competes in the Great Flume Race in 1987, photo by Erik Gordon Bainbridge

“The timing of it all was perfect,” recalls Kimbrough. “Mountain biking was growing fast, and Max and Patti had just started promoting the race on a trail nobody had ever seen before with some of the best views anywhere.”

As word got out about the Flume Trail, its popularity exploded, with photos of Lake Tahoe on magazine cover after magazine cover. People from around the world came to Lake Tahoe to ride the Flume Trail and race in the event.

Eventually, it became so popular that more than 200 racers showed up on the same day hundreds of recreational hikers and mountain bikers were on the trail, and the event got to be too much, bringing an end to the race.

But after a 12-year run, the Great Flume Race had served its purpose: It put the trail on the map. It also established a lifelong career for Jones.

In 1998, thanks to his achievements in the sport, Jones was inducted into the Mountain Bike Hall of Fame. The next year, he received a permit from Nevada State Parks to provide shuttles for mountain bikers back to Spooner Summit after they finished riding the Flume Trail. Between running the cross-country ski center at Spooner Lake in winter and Flume Trail Bikes in summer, Jones and his wife Patti were pioneering eco-tourism in Tahoe.

Max Jones was inducted into the Mountain Bike Hall of Fame in 1998, photo by Ryan Salm

After a few years of running the shuttle business, Jones met his future landlord, Craig Olson, who had recently purchased part of the historic Ponderosa Ranch at Tunnel Creek along Highway 28. Jones had been picking people up with his shuttle van along a shoulder on the side of the highway, which was not an ideal spot.

“It was always my dream to have the shuttle business at the end of the trail at Tunnel Creek,” says Jones. “So when Craig approached me and said, ‘You should pick people up here,’ I immediately said, ‘OK.’”

After five years of Jones operating from the cross-country center at Spooner Lake, Olson suggested he move the whole operation to Tunnel Creek. Jones jumped at the opportunity, opening Tunnel Creek Café alongside Flume Trail Bikes in 2012, because the only thing better than a mountain bike shuttle is a beer and sandwich at the end of the ride.

The Joneses recently sold the restaurant, but the couple still owns Flume Trail Bikes, and it’s going stronger than ever.

Understated Steward

Fellow Mountain Bike Hall of Fame member Scot Nicol, founder and co-owner of Ibis Cycles—established in 1981 as one of the original mountain bike brands—has known Jones for nearly 40 years.

“Max is such a rock star in so many different ways, from mountain biking, skiing and rock climbing to running multiple successful businesses and resurrecting the Flume Trail,” says Nicol. “But what I love most about Max is how understated and humble he is about all of it. He doesn’t draw attention to all the significant achievements he’s had over the years.”

In addition to being at the forefront of eco-tourism in Tahoe, Jones has long been an influential voice for trail access. According to Kimbrough, his involvement with the Tahoe Rim Trail Association (TRTA) was pivotal in expanding trail access for mountain bikes.

Max Jones, the legend, photo by Ryan Salm

“In the late 1990s, I was president of the TRTA, and there was a lot of turmoil between mountain bikers and hikers,” says Kimbrough. “Mountain bikers didn’t have a great reputation, and since everyone respected Max, he stepped up to represent the voice of mountain bikers, serving on the board of the TRTA. His efforts are the reason why the Tahoe Rim Trail is open to mountain bikes today.”

Thanks to Jones’ advocacy efforts, expanded riding opportunities keep coming.

Last summer, Carson City-based trails advocacy group Muscle Powered completed the Capitol to Tahoe Connector trail, a new 10-mile route linking the Tahoe Rim Trail at Marlette Campground all the way into Carson City on the Ash to Kings Trail. Additionally, the Tahoe Area Mountain Biking Association (TAMBA) and Great Basin Institute are close to completing a 2.2-mile singletrack connecting the north end of the Flume Trail to Tunnel Creek, bypassing the sandy, steep, winding and very busy Tunnel Creek Road.

The expanded trail access will only enhance an experience Nicol regards as one of the world’s most unique mountain bike rides. Nicol has been fortunate enough to travel extensively with his bike over the years, riding in some of the world’s most beautiful locations, including the French Alps—but to him, there’s nothing like the Flume Trail.

“The Flume Trail above Sand Harbor is one of the most spectacular moments anyone could ever have on a mountain bike,” says Nicol. “And because of how easy the Flume Trail is to access, Max has given a magical experience to people who don’t even consider themselves mountain bikers. Anybody who can ride a bike can witness one of the most beautiful trails on the planet, and that’s the true gift of Max and the Flume Trail.”

The story of Max Jones and the Flume Trail is the story of a man who built a career around a trail. Four decades later, he is celebrated as a pioneer, carving out a niche that’s benefited hundreds of thousands of visitors and the entire Lake Tahoe region.

As a freelance writer and co-host of Mind the Track Podcast, Kurt Gensheimer has a passion for storytelling, trails and mountain biking. In 2018 Gensheimer began resurrecting the Toiyabe Crest Trail near Kingston, Nevada, inspired by the efforts of Max Jones and the Flume Trail. Follow him on Instagram, @trail_whisperer and @mindthetrack.

Max Jones’ Mountain Biking Achievements

× Created Tahoe’s famed Flume Trail, 1983

× Professional cross-country racer, 1984–1996

× NORBA board of trustees rider representative, 1989-91

× Tahoe Rim Trail board member since September 1997

× Team manager for the U.S. National Worlds Team, 1995-98

× KONA Professional Team Manager, 1992-97

× US National Team member, 1990, 1992, 1993

× Second in 1986 National Championships

× First overall in 1986 Fat Tire Bike Week Stage Race

× Third in 1988 National Championship Series

× Fourth in 1989 National Finals

× Third in 1989 World Cup Finals

× Fifth in 1990 World Championships

× Veteran National Champion, 1992, 1993

× Fifth in 1992 Veteran World Championships

× Eighth in 1997 Master World Championships 40-49

× Inducted into Mountain Bike Hall of Fame, 1998

PT in PC

Posted at 16:18h, 14 AugustGreat article. I just (re)rode the trail last weekend including the new, and very welcome, north section. It had been 20 years since the last time. I love that the planets aligned and a bunch of hard work by Max made this gem possible. I was wondering about the aluminum pipes, but now I know. Thanks for this article!