27 Sep A Creative Spark

After a successful career as a furniture designer and builder, Randall ‘Sparky’ Kramer has developed into one of the best luthiers in the business

Randall Kramer’s Truckee home, which includes a well-appointed workshop on the lower floor, photo by Ryan Salm

Nestled in a quaint corner of Truckee, a two-story building clad in rusted corten steel resides harmoniously among its surroundings—aspens quaking gently in the breeze, sturdy pines stretching skyward, a bountiful garden.

In many ways, the modest structure is a reflection of the man who designed and built it from scratch.

Indeed, Randall Kramer—better known as “Sparky”—is every bit as unpretentious and hardworking as his home and workshop, where a humble yet functional exterior gives way to a well-appointed interior with every tool a woodworker could ask for.

“I basically built my dream shop with a house fit in upstairs,” says Kramer, describing his home, which he built with a crew of friends in 1987 and ’88, as an “owner-builder, finish-before-you-die kind of project.”

Kramer has spent countless hours in the three and a half decades since skillfully crafting wood from the cozy confines of his shop. But after building a reputation around Truckee and Tahoe as an expert furniture maker, the 73-year-old, nearly lifelong woodworker has carved out a successful career as one of the best luthiers around.

“He’s good. He goes to all the shows and brings his guitars, and they line up with the best guitars probably in the world,” says Steve Kershisnik, a longtime Truckee resident and professional musician.

Achieving “super luthier” status, as Kershisnik credits his friend, did not happen overnight. Nor did it come easily or without some good fortune. While Kramer has long possessed the ability to perform such a skilled profession, it wasn’t until he got into the shop of a master teacher that he gained the knowledge and foundation to become what he is today.

Now, some 20 years after building his first guitar, Kramer’s instruments are a sought-after commodity for those seeking the ultimate in quality, while his restoration work is second to none.

“He’s the top dog,” says Kershisnik. “Everybody goes to Sparky.”

Kramer’s Truckee workshop, photo by Ryan Salm

Long Before Becoming a Luthier

Kramer has enjoyed working with his hands since he was a child growing up in Southern California, where he says Popular Mechanics and The Boy Mechanic always had a prominent place on his family’s bookshelves.

“My mom bought me some woodworking tools when I was a kid and kind of turned me loose,” says Kramer, who quickly took to the craft—to the point he was soon building his own wooden toys.

Although mostly self-taught, says Kramer, he further honed his skills in junior high shop classes. He went on to buy a Ford woodie in high school and before graduating had replaced all the bad wood and refinished it himself. “I never thought I couldn’t do something, so I just did it,” he says.

After high school, Kramer worked as an auto mechanic while attending Riverside City College with thoughts of becoming an architect or engineer. But he scrapped the plan when he realized he would not be happy spending his days inside an office.

He instead became a whitewater rafting guide, working on rivers from California to Idaho to Alaska during the summer months. The gig allowed him the opportunity to delve into a hobby he only dabbled in previously: playing guitar.

“I played guitar off and on since junior high school, but when I was river guiding I played a lot because that was something we did,” he says. “I ended up working for a company that had a lot of musicians, so we would sit around the campfire after dinner and we would play music, and people loved it, and we loved it.”

Eventually, however, Kramer longed to settle down with his then-girlfriend.

“I kind of did this evaluation of, ‘OK, what are you good at? What are you going to do? You can’t be a river guide your whole life.’ I was good at woodworking, so I put my heart and soul into it and ended up in Truckee eventually,” says Kramer, who moved from Sonora in the foothills near Yosemite to Truckee in 1983 to help a friend build a house.

Kramer, who started his own woodworking business while living in Sonora, bought a 3-plus-acre property bordering Sierra Meadows in 1985. A few years later he was churning out furniture from the shop he built by hand.

In addition to furniture, Kramer performed cabinet work and got into building bar tops and tables for local restaurants, including Pianeta, Cottonwood and Christy Hill, to name a few. Among the highlights of his work, he notes creating inlaid checkerboards on several tables for Squeeze Inn in downtown Truckee, as well as abstract musical notation embedded in a bar top at The Passage (now Moody’s Bistro Bar & Beats).

“I heard that the contractor who did the remodel to create Moody’s kept the bar for his own home,” says Kramer.

A custom Randall Kramer Guitar, photo by Ryan Salm

Acquiring a New Skill

Kramer has long been a fan of Norman Blake. So when he saw that one of his favorite musicians was playing at the Millpond Music Festival outside of Bishop—“this must have been back in the 1990s,” he says—he made the trip south for the three-day show.

That’s where he met Mark Blanchard, who would change the trajectory of his career.

“Mark Blanchard had a little display with the first six guitars that he had built. So he was in his infancy of guitar-building, but he’s the kind of guy who will hit the road running,” says Kramer. “My wife and I spent a fair amount of time in his booth playing his guitars, and I was just totally floored by the sound he was getting out of them.

“Everywhere I go I play people’s instruments, and I had never met anyone who could consistently build a good guitar,” adds Kramer, who considered himself somewhat of a guitar collector at the time. “It was always a crapshoot. It’s why I never really pursued building guitars, because I wouldn’t have known what I was doing to get a good-sounding guitar. At that point I figured I could buy a good-sounding guitar.”

Kramer remained friends with Blanchard and continued to follow his work over the years. When Blanchard mentioned he would like to teach someone how to build a guitar, Kramer jumped at the opportunity. Due to his busy work schedule, though—Kramer says he had a two- to three-year backlog for his furniture—a few years went by before the two connected in 2001 for a two-week guitar-building lesson at Blanchard’s Crowley Lake shop.

“Sparky was great to work with,” says Blanchard. “By the time he came to me he had decades of furniture-making experience. So he arrived with his own tools, which was nice. We did the teaching in my workshop, but it was great because he had these woodworking skills, and I could just say, ‘This is what you need to do,’ and send him off to the machines and I didn’t have to worry about him coming back with a finger missing or something.

“So in that respect it was really a pleasure. All he really needed to know was the particulars of how to put a guitar together. He was already familiar with the materials and the tools. He was a perfect subject.”

By the end of the two-week session, Kramer had “pretty much built a guitar,” which he brought back to his shop for some finish work before returning to Blanchard’s to finalize the project.

“I still have that guitar,” says Kramer.

Although he did not anticipate becoming a luthier, after making that first guitar, he figured he’d better build another one before he forgot what he had learned. So he did. In the process, he says he spent about 80 percent of his time building all the necessary tools—jigs, templates, bending forms, etc.

“Really that second guitar was building all the fixtures to build the guitar. And then once I had those, I figured I might as well build another one, and then one thing led to the next,” says Kramer, who also spent a significant amount of time on the phone with Blanchard asking for advice. “My goal with building my third guitar was to complete it without calling Blanchard.”

The following year Kramer had business cards printed, and in 2003 he showed his work at the Healdsburg Guitar Festival. He had officially, though unintentionally, become a luthier.

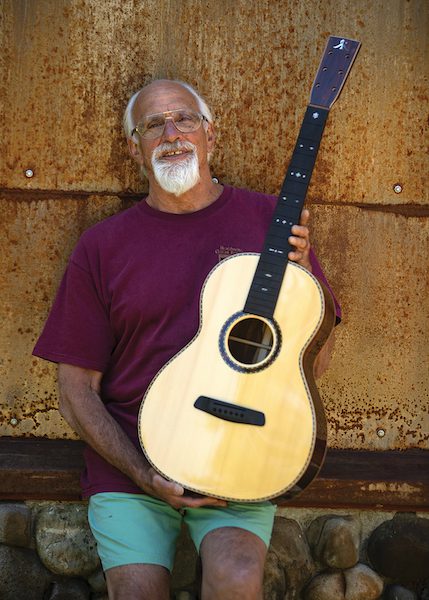

Kramer, known by most as “Sparky,” holds one of the 70 or so guitars that he has built since 2001, photo by Ryan Salm

Mastering the Craft

While Blanchard taught Kramer nearly everything he knows about building guitars, perhaps the most crucial takeaway from their training session was the understanding of Chladni plate tuning. It’s complicated, but the technique—borrowed from violin makers—is a method of tuning based on the vibrations of a resonating instrument’s top and back. By manipulating the wood used to build the guitar, a luthier can achieve the desired resonant frequencies throughout the instrument’s vocal range.

“One of the big things we did was I taught him what I knew about voicing a guitar,” says Blanchard, referencing the tuning method. “It’s one thing to just do the woodwork and put a guitar together; it’s another to know how to manipulate the tone of the instrument. And that’s all done through the way you construct it—the dimensions, the bracing patterns, the wood thickness and all that kind of stuff.

“I had developed my own little system for that, and I taught that to Sparky. And to this day, you can play one of his guitars and one of mine and there are some fundamental similarities, which I think is kind of cool.”

Kramer further explains that certain types of wood— spruce, for example, is coveted for its stiffness and low density—are better suited for a given player’s style. Whether that musician plays aggressively or with a light touch determines how Kramer constructs the guitar, and with what type of wood. In addition, if a customer is seeking a guitar to accompany singing, Kramer also considers how the instrument’s sound pairs with that musician’s voice.

“That guitar’s voice has to be compatible with their voice,” he says. “So if I’m building a guitar for a singer, I’m getting him to sing and play guitar, and I’m looking at what kind of voice is going to accompany their voice best. A lot of singers never think about that, but a lot of times they’re playing a guitar that’s competing with their voice. It’s not complementing their voice at all.”

And that is what sets Kramer’s and Blanchard’s guitars apart from the average instrument.

Kershisnik, a multi-instrumentalist and private music instructor who plays with numerous local bands—The Blues Monsters, Brian Hess Music, Mike Schermer Band and Everyday Outlaw, among others—says he was tuning a piano for a friend one day when the friend asked if he’d ever played one of Kramer’s guitars. He had not.

Musician David Goldman plays Kramer’s Prairie Grass 12 Fret model guitar with an Italian spruce top and koa back and sides

“He brought out this guitar, which was beautiful, and it was one of the best guitars I’ve ever played,” says Kershisnik. “I’ve played Martins and Taylors and Gibsons, the whole nine yards. So I could tell he had that attention to detail that you need (to be a good luthier).”

Kershisnik, who describes his friend as a “super nice, soft-spoken cat with a sly sense of humor,” has since had a guitar and bass repaired by Kramer. “I could have probably fixed the bass myself, but it wouldn’t have been perfect,” he says.

Such reports from satisfied customers are key to Kramer’s success. He’s earned his reputation from both local referrals and guitar shows across the country. For example, he recently returned from a show in Chicago called the Fretboard Summit. While he didn’t sell any of the guitars he brought, he met a lot of musicians and guitar aficionados who are now familiar with his work.

“It’s all about making contacts and getting your stuff in the hands of players and keeping the buzz rolling about you as a builder. You’ve got to get people talking about you. That’s kind of how the orders roll in,” says Kramer, whose guitars are spread far and wide due to the number of shows he attends nationally (the next one on his calendar is the Woodstock Invitational Luthier Showcase in New York in late October).

With Kramer’s reputation for high-end work established and his skills ever-evolving, his guitars—both new and restored—will continue to find happy homes.

“I’ve built almost 70 guitars now,” he says. “I’m not as prolific as some of these guys are, but I don’t want to be.”

To learn more about Kramer and his work, visit randallkramerguitars.com.

Ryan Salm is a photographer and writer based on Tahoe’s North Shore. Sylas Wright is TQ’s Truckee-based editor.

No Comments