07 Jun George Whittell, Jr.: The Accidental Conservationist

Through the wafts of cigarette smoke, the clinks of whiskey glasses and the inebriated squeals of a few straggling showgirls regularly employed at the Cal-Neva, it becomes apparent that Ty Cobb has a full house, while Howard Hughes leans on his two of a kind—both of which prove futile as George Whittell Jr., patriarch of the Thunderbird Lodge, lays down his straight flush in graceful triumph.

This poker game featuring some of Lake Tahoe’s more notable denizens may be ripped from history, but like most of the anecdotes that comprise the famed region’s lore, it is susceptible to the storyteller’s natural tendency toward embellishment.

Tall Tales

Lake Tahoe, as a playground for the affluent for more than a century, has hosted more than its fair share of decadence. However, Whittell arguably sits atop Tahoe’s immense Bacchanalian heap, king of Revelry Mountain.

An eccentric playboy with the good fortune to be born into money, Whittell never worked a day in his life, ran away with the circus instead of going to university, married a succession of dancers and showgirls, sped around in his fleet of luxury Duesenbergs with a lion riding shotgun, and bought and preserved nearly the entire Nevada portion of Lake Tahoe.

.jpg)

Whittell’s pet lion, Bill, was a gift to Whittell by his former second wife on the occasion of his marriage to his third wife.

Following their divorce, Josie Cunningham Whittell and George Whittell remained close. So when he remarried in 1919,

Josie thought the then young cub would be a perfect wedding present for her friend. Little did she know that Whittell

and Bill would become inseparable.

However, Bill Watson, executive director and curator of Thunderbird Lake Tahoe, which has turned Whittell’s spacious mansion into a museum, points out that the society pages of newspapers at the time, which provide the foundation of the lore surrounding Whittell, were more than a little prone to exaggeration.

“The wealthy of that time liked to see scandalous stories printed about themselves à la The Great Gatsby,” Watson says. “So, as a result there were exaggerated tales of Mr. Whittell’s exploits, some of which happened, most of which did not.”

Regardless, Watson is correct in asserting that Whittell’s life was not all tawdry intrigue, ceaseless orgies and torrid love affairs.

Whittell was made a Knight of the Order of Leopold by the King of Belgium for his distinguished service as an ambulance driver in World War I, where he served alongside Ernest Hemingway. Whittell further attempted to sign up as a volunteer in the army on December 8, 1942, at the ripe old age of 60 (he was denied, much to his chagrin).

Upon his death, he left a large share of his fortune to the National Audubon Society, Defenders of Wildlife and the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. He was fluent in seven languages, a gracious host and a major if unwitting conservationist.

The picture of Whittell is complicated—gilded by the excesses of his age, worn by the accusations of the more staid members of the San Francisco upper crust. His reputed selfishness is contradicted by his sacrifices and service for his country. His vaunted appetite for high society is contrasted with a propensity to be reclusive and solitary. All of this complication is further muddled by the exaggerations unique to the tabloid coverage of his exploits and historians’ own tendency to print the legend in lieu of the facts.

One of the first photos following George and Elia Whittell’s occupancy of Thunderbird Lodge in 1937 or 1938. A second round of construction to

add terraces and faux chimneys had not yet commenced. Note the wind turbine at the base of the flagpole. City power did not arrive until 1939:

until that time, Whittell generated power using wind and water from Marlette Creek.

The Man Versus the Myth

Whittell was born in 1882, scion of one of San Francisco’s wealthiest families. His father, George Whittell Sr., made his money in real estate during the Gold Rush and was one of the founders of the Pacific Gas & Electric Company.

The Whittells maintained a respectable house across the street from Charles Crocker and established a sprawling estate in Woodside, California, a few miles south of the city.

Whittell’s twin brother, Nick, died at age four, leaving George Jr. as the sole heir of his family’s fortune.

Junior did not inherit his father’s conservative predilections; instead, he ran away with the Barnum & Bailey Circus as it toured the country at a time when most of his contemporaries were chasing university degrees.

In 1903, the young tycoon met and married Florence Boyere, a young dancer. The marriage embarrassed his parents; his father paid an enormous sum to have it annulled and dispatched $25,000 to Boyere for her troubles. Uncowed, Whittell married yet another woman of the spotlight, Josie Cunningham, a year later.

Their marriage did not prove durable. They divorced in two years.

Whittell then bounced from affair to affair. He is reputed to have said: “When men stop boozing, womanizing and gambling, the bloom is off the rose.”

But it wasn’t all floozies and fun. Whittell proved an adroit manager of the family fortune after his father died in 1922. In 1929, only months before the Great Stock Market Crash, Whittell liquidated more than $50 million worth of stock—a move that saved his family’s enormous fortune.

By then, he had married a woman he met while serving meritoriously in World War I, a French debutante named Elia Pascal. Pascal differed from the showgirls of his youth. She, like Whittell, came from wealth, as her parents owned a large estate in France’s picturesque Loire Valley.

The marriage was durable, but elastic. Pascal was with Whittell at his Woodside deathbed in 1969 when he died of melanoma at the age of 87, but the couple spent most of their marriage in separate countries, as Pascal preferred to reside in Paris while Whittell is rumored to never have quite rid himself of his affinity for showgirls.

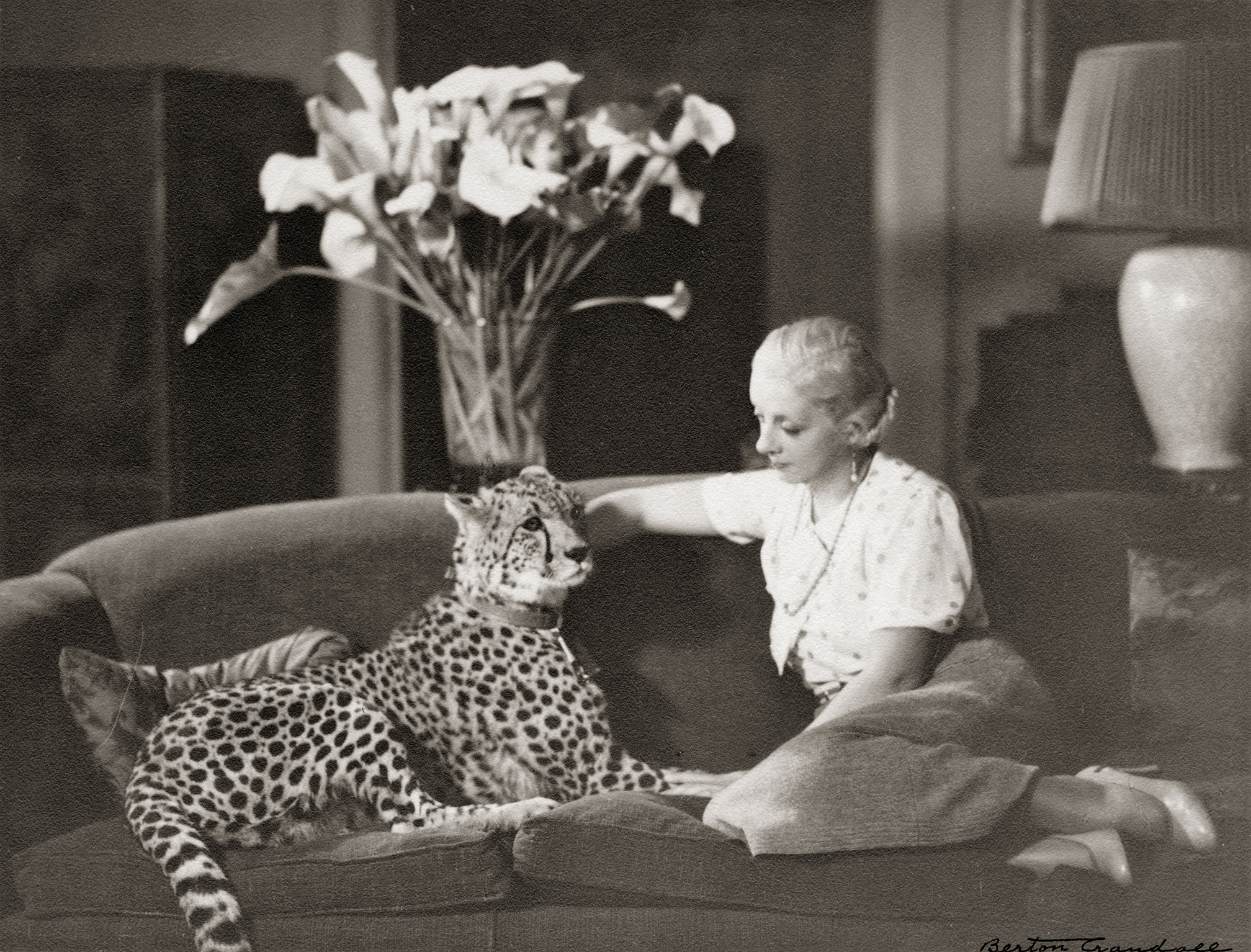

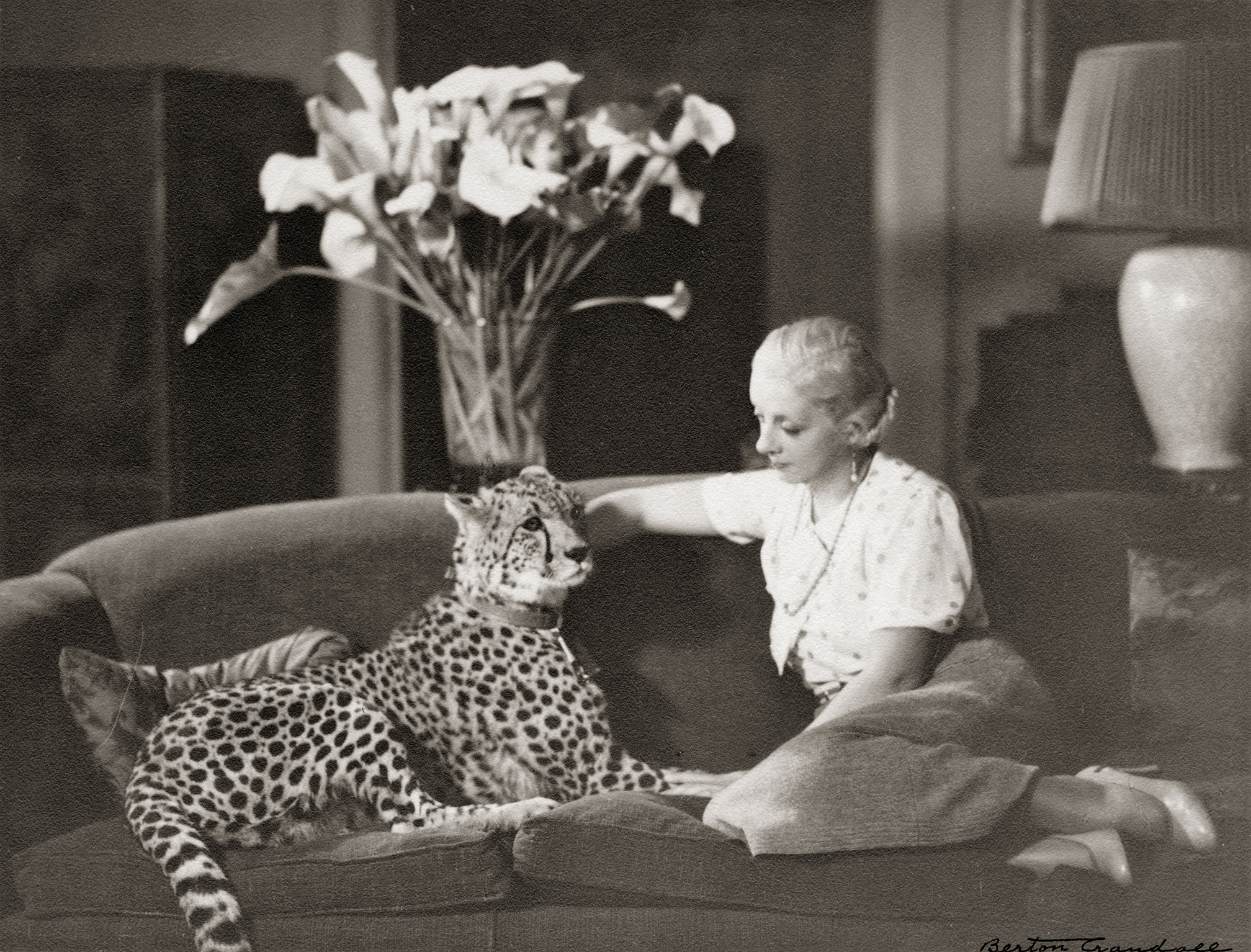

George Whittell’s third wife, Elia Pascal, loved animals, too. She had two pet cheetahs whom she treated as house cats

Whittell’s Thunderbird

Whittell originally absconded to Nevada around 1930 because its reputation as a tax haven accommodated his need to protect his vast inheritance from the intrusive hands of the state of California.

He began real estate hunting in the early 1930s, as most of the American population was in the initial throes of the Great Depression.

Tahoe as a destination for the wealthy was in ascendancy, so Whittell zeroed in on The Lake’s East Shore, where the trees had all been cut and conveyed down to the mine shafts of the Comstock Lode in Virginia City. The tycoon purchased a wide swath of land, including 45,000 acres and more than 20 miles of Lake Tahoe’s inimitable shoreline. The land closest to the shore cost about $6 an acre, while land higher up ran a meager $3 an acre.

The construction of the house, replete with its secret passageways and outlying buildings, cost about $300,000 all told—a fair chunk in the ’30s; Whittell took out a building permit in 1935 for $5.50.

Whittell’s original intention was to augment his own estate with large-scale development, with plans for large casino and hotel resorts in Zephyr Cove and Sand Harbor.

But after his remote stone mansion was completed in 1936 and he moved in around 1937, his appetite for the development vanished.

“One can imagine that George Whittell looked over the pristine landscape from his home and torpedoed his own development plans,” Watson says.

Whether by land or by sea, the Thunderbird Lodge offers the beholder an impressive sight. Perched on a rocky promontory formerly known as Observation Point, the three-story Tudor Revival stone manse, designed by Reno architect Frederick De Longchamps, resembles a combination of a gallant French chateau and a fortress aimed at preventing an invasion from Tahoe’s West Shore.

Of course, a fortress it was not, though Whittell, particularly in his latter years, did retire to the mansion and its vast surrounding estate as a means of keeping the outside world at bay.

A unique feature of the Thunderbird Lodge is its custom-made elephant pen. It was constructed to house Mingo, Whittell’s 600-pound pet Sumatran elephant, a memento of his youth spent with the circus.

Mingo was one of Whittell’s two pet elephants. Because Whittell planned to fly Mingo to and from

the Bay Area by seaplane, and that seaplane crashed twice in Lake Tahoe, it has been long-rumored

that Mingo is at the bottom of The Lake. This is not true, as Mingo was not aboard and, both times,

the plane crashed near Sand Harbor, was hauled ashore, and repaired to fly again.

Watson has seen pictures of Whittell with the elephant at the Lake Tahoe estate. Rumors persist that Whittell also allowed his pet lion, Bill, to roam the grounds at Thunderbird Lodge, frightening off a few hapless trespassers over the years, but these tales have grown rather tall, Watson says.

“There’s a picture of him driving with a lion in the front seat of his Duesenberg and suddenly that story becomes he has lions and tigers up here at the Thunderbird,” Watson says.

Much of the lore surrounding Whittell’s time in Tahoe is steeped more in myth than truth, Watson says.

The legendary parties at Thunderbird certainly occurred, but they were rare. While Whittell hosted friends and family, the mansion was built in a manner that discouraged overnight visitors.

Nevertheless, the stories about Whittell using a dungeon in the basement for guests who over-imbibed certainly persist.

But more often, particularly as Whittell grew older, he was alone at Thunderbird. For every night he invited baseball legend Ty Cobb and fellow eccentric millionaire Howard Hughes over for poker, there stretched a longer duration where he consorted with nobody but his exotic pets or a favored mistress.

From 1937 to 1968, Whittell repaired to his Lake Tahoe retreat every summer. During this period, Whittell commissioned the construction of what some deem the world’s most recognizable speedboat.

The Thunderbird Yacht is a 55-foot wooden boat capable of hitting 60 knots due to the twin V-12 550 horsepower Kermath engines. It is under repair now, but it still roams the crystalline surface of Lake Tahoe, its aggressive engines announcing its presence in no uncertain terms.

To house the boat, the reclusive millionaire ordered the construction of a boathouse the size of a basketball court blasted out of the granite and a 600-foot tunnel that connected it to the main house.

Preserving the East Shore

Whittell died in 1969, but prior to his death, he sold off pieces of his vast estate to Nevada State Parks and other management agencies. At the time of his death, he still owned the house and about 10,000 acres of surrounding property, which was purchased by Wall Street maven Jack Dreyfus, then later sold with most of the estate to the U.S. Forest Service.

In 2009, the Thunderbird Preservation Society, of which Bill Watson serves as executive director, assumed ownership of the building and approximately 140 acres of surrounding land. The nonprofit has transformed the mansion into a museum that pays homage not only to the life of its eccentric former owner, but to Lake Tahoe’s rich and illustrious history in general. A popular tourist attraction, the Thunderbird Preservation Society offers guided tours by foot, by boat or by kayak Tuesday through Saturday, from mid-May to mid-October.

Reservations are required for all tours. For more information, call 1-800-GO-TAHOE or click here.

In the meantime, remember that while Whittell’s legacy is bound up inextricably with his appetites, his whimsies, his parties, his hobnobbing with the faded luminaries of a bygone era, his pets and his reclusive eccentricities, his true legacy lies in the unspoiled nature of Lake Tahoe’s nearly development-free East Shore. While the other three shores are dotted with casinos, ski resorts, alpine cabins, restaurants and development, Whittell’s decision to indulge his need for solitude rather than line his pocketbook means ensuing generations are free to enjoy an unspoiled version of Lake Tahoe. A more natural Lake Tahoe, courtesy of Whittell.

Matthew Renda is a Santa Cruz–based writer.

Liza Casey

Posted at 11:43h, 22 DecemberGeorge Whittell was brilliant. He did love beauty, which included beautiful women but it was the marriage of the minds with the women who were close to him. His wife stayed in France one year out of every 4 years… Though the summers she did not come up to Tahoe after the 1950s. Too rustic. She was highly cultured and taught Mr Whittell much in that regard. They did have separate living quarters in Woodside estate. She had a large bedroom with walking closets, sewing room and study upstairs while GW had his bedroom, large study and a large, mostly glass, room for his electronics. He was very interested in the developments of the computer in the 60s. He would be in awe of how far we’ve come.

Though he did like practical jokes it was out of a curiosity of how people react and what makes them tick…with a deep respect for nature. (human, plant and animal…)

Trying to say he was more than a player and how profoundly wise he was didn’t come out so well in above description… Could go on and on. Must be this shut down… Thanks for offering a space to share.

Carole

Posted at 13:52h, 05 AugustDid a very loved girlfriend of his crash & die in a car near Crystal Bay, Nevada?

He kept the smash car for years above his Thunderbird Lodge property?