30 Apr The Last Prospectors

Placer miners continue to pan Sierra streams, gripped by the same gold fever that shaped California

James Dee and Keith Mullenix are sitting on the steep bank of the North Fork American River at Mineral Bar, just outside of Colfax. It’s late afternoon, and though James nudges Keith and declares they ought to pan the traps farther downstream before they lose the light, his suggestion lacks sincerity. And anyway, Keith hasn’t been listening for the past several minutes.

James falls silent, takes a sip of Keystone, and considers the river. For a long moment, all is still. Only the water moves, and even it is barely perceptible. Here, the river unspools from its upstream ferocity, slowing and widening as if to prepare for the canyon downstream, through which it will tighten into a coil of thundering rapids.

Both men stare at the river, or, perhaps, through the river. Its shallow clarity promises untold treasures, and in the glimmering half-light, that promise almost feels real. James and Keith are a little drunk and a little stoned, and they have at last given in totally to that element of gold hunting that has undergirded the activity since man first lusted after the gleaming mineral: The Dream.

The dream is not exclusive to finding gold, although any prospector worth his salt can feel the weight of the elusive nugget in his hand at all times. Rather, the dream is whatever quality first compelled a man or woman to abandon the life they had constructed and pick up a spade and a sluice and head to the river.

Perhaps even that is too articulate. Gold hunting is not about one dream or vision, but the freedom to surrender one’s life to dreams and visions.

Living the Dream

Keith stirs and takes a hit from his pipe. “The river tells the story,” he says. “You’ve just got to listen.”

It is not clear which story, exactly, the river is telling, and likely that is the point. The fact that good stories still exist to be told and heard is sufficient. For Keith, whose current narrative will end either asleep in his car tonight or in the bed of a motel he can barely afford, slipping into a story that is beautiful, if perhaps fictitious, has an irresistible appeal.

“This is why we come to the river,” he adds. “Finding gold is just a bonus.”

If it seems that very little gold hunting occurs while hunting for gold, that is not entirely false, nor entirely true. It depends on the day and the hour, bad weather or difficult terrain, the surfeit or scarcity of food and water, and the overall feeling of good or bad luck.

Unstructured and unconventional, yes, but real prospecting is no Sunday stroll.

In his two decades of prospecting, James estimates he has found about 20 ounces of gold, roughly $25,000. Though he enjoys an end-of-the-day six-pack, you don’t find 20 ounces of gold—28 grams in an ounce, countless gold flakes in a gram—by just sitting and drinking.

“This is the hardest work I’ve ever done,” says Keith, whose career in construction earned him a bad back and a disability check. “I’m not making enough from disability and social security, so I’m having to grind it out and make some extra money.

“But I never feel like I’m working when I do this,” he is quick to add. “If you got gold you’re coming back.”

Mike Terronez knows. Stooped over his sluice box in an eddy a quarter mile upriver from James and Keith, he’s still hard at work, a term meant only to denote physical exertion. The former service advisor for BMW hasn’t engaged in those other definitions of work—duty, responsibility, salary—in several years.

“I was the third top service advisor in 2014, but I put the corporate world down for this,” he says, water surging past his waders. Mike stands for a long moment in silence, as if to let the river make a formal statement. “The corporate world…” he mutters.

Mike Terronez is deep in concentration as he pans a shallow eddy along the North Fork American River. “Gold has accumulated in these areas down to the bedrock over thousands of years,” he says. “Anywhere there’s a crack, crease or crevice, there might be gold.” Photo by Michael Rohm

Mike Terronez is deep in concentration as he pans a shallow eddy along the North Fork American River. “Gold has accumulated in these areas down to the bedrock over thousands of years,” he says. “Anywhere there’s a crack, crease or crevice, there might be gold.” Photo by Michael Rohm

Compared to James’ 20 ounces in 20 years and Keith’s 5 ounces in eight years, Mike is a beginner. But his relative inexperience—about an ounce of gold in two years—is belied by his wealth of knowledge. An electrical engineer by trade, Mike came into prospecting with a running start.

“Being an engineer has helped me a lot,” he says. “Guys spend thousands on their gear and I just spent days in my shed.”

The shed is in Parma, Idaho—nominally his home, though he has been camping along the American River for several months now—and those days occurred in the grips of a long, cold winter, during which Mike caught gold fever before he even “saw color,” prospecting slang for pulling up gold.

“We were hunkered down for four months in Idaho because of the snowfall,” he says. “I spent a lot of time on YouTube figuring out how to make equipment, then I turned my shed into a gold mining production plant.

“That got me into a little trouble with the wife,” he adds, chuckling.

According to Mike, his last name translates to English as “Son of the Earth,” so it is no wonder he took to prospecting with such fervor. If genetic clichés are to be believed, he was born with it in his blood.

“Hey, look at that!” Mike bends low over the sluice and points to a tiny golden sparkle high in the wire riffle. “Gold!” he says with a lover’s sigh. “That’s really pretty.” He stands and surveys the verdant canyon around him, his arms outstretched expansively.

“Look how beautiful it is out here. Yes, gold is very pretty, and yes, you can get the fever, but I think that’s just an excuse. Being out in nature is the real attraction.”

According to Keith Mullenix, there are many reasons to pan for gold—freedom from the daily grind, a simple existence in the natural world—but gold is what keeps you coming back: “When you get the fever, you’ll be here every day after work and every weekend. It’s like playing the lottery without buying a ticket.” Photo by Michael Rohm

According to Keith Mullenix, there are many reasons to pan for gold—freedom from the daily grind, a simple existence in the natural world—but gold is what keeps you coming back: “When you get the fever, you’ll be here every day after work and every weekend. It’s like playing the lottery without buying a ticket.” Photo by Michael Rohm

Driven by Gold

People like James and Keith and Mike exist as fading iterations of a distinctly American identity: explorers on whose backs the West was built; transients for whom the frontier has always sang with the voice of a siren. It is singing still, even when it seems the last frontiers have long since vanished.

Before the events that launched the Gold Rush of 1849, there were vagabonds just like the three men panning the American River on this mild winter day. It is fitting that such restless wanderers continue to manifest their destiny a century and a half after the destiny died.

But such men did not settle California. Gold did that.

“The allure of California was already there, but the gold strike put American emigration into overdrive,” says Mark McLaughlin, a Tahoe-based historian and author. “The rush of ’49 gave California a huge jumpstart.”

Gary Kurutz, executive director of the California State Library Foundation, agrees.

“People saw gold as a grand opportunity,” says Kurutz, who authored an 800-page descriptive bibliography of the Gold Rush. “Without gold, California might have taken as long to develop as Oregon or Washington did.”

In terms of settling the soon-to-be state, the Gold Rush couldn’t have been better timed if California herself had hung vacancy signs along her borders.

When the Mexican–American war ended on February 2, 1848—nine days after sawmill operator James Marshall absentmindedly plucked a nugget of gold from the American River—thousands of soldiers in the hot sun of the nation’s newest acquisition suddenly had no more war to fight. Following the Treaty of Gaudalupe Hidalgo, the newly ceded California was no longer a foreign warzone, but an American paradise for a horde of single young men.

“The Gold Rush was exquisite timing for a lot of these soldiers coming out of the end of the Mexican–American war,” says Kurutz. “This was a great opportunity to stay out of the tedious, humdrum life back in New England. This was a place you could be free.”

That sentiment was shared by millions on the East Coast and around the world by the start of 1849. News of California’s gold discovery began to trickle across the continent throughout the summer and fall of 1848, but it wasn’t until President James Polk himself confirmed the discovery that the trickle became a flood.

On December 5, 1848, following a number of private testimonies of gold-bearing officers returning from the Mexican–American war, Polk commented on the matter in his State of the Union address, thinly disguising his own “gold fever” behind circumspect eloquence.

“Recent discoveries render it probable that these mines are more extensive and valuable than was anticipated. The accounts of the abundance of gold in that territory are of such an extraordinary character as would scarcely command belief were they not corroborated by the authentic reports of officers in the public service… ”

In that era of American expansionism—made fervent by a president so committed to the ideals of Manifest Destiny that he increased the size of the United States by two-thirds, more than any U.S. president before or since—the writing of the rush was on the wall.

“There’s been plenty of gold discovered in the history of human civilization,” says McLaughlin. “But those were in empires where all the wealth went to kings, queens or rulers. The California Gold Rush was the very first time an individual could buy a shovel and a pick and become a millionaire almost overnight. It opened the door to the greatest voluntary migration in human history.”

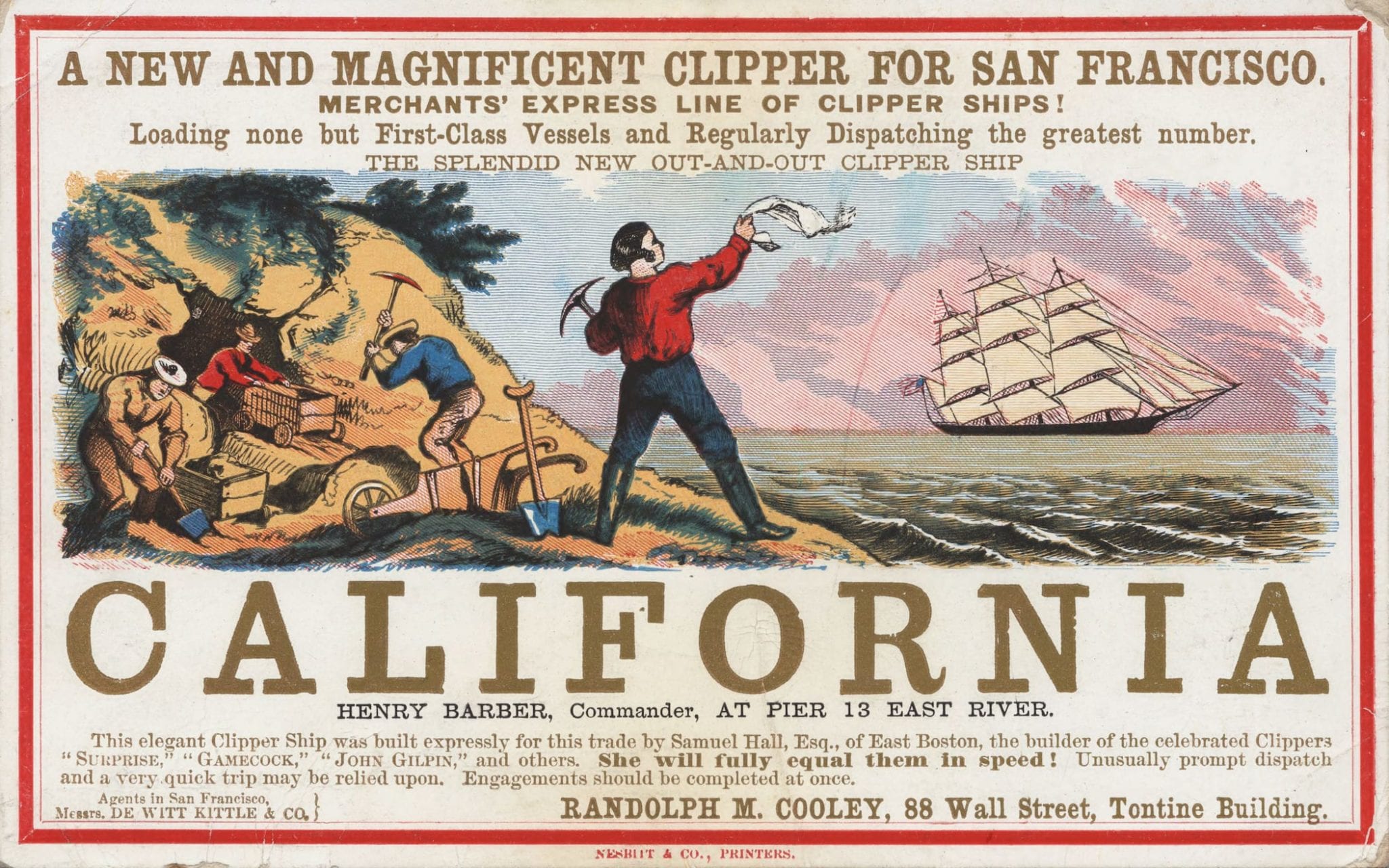

An ad encourages sailing to California, circa 1850, courtesy G.F. Nesbitt & Co.

An ad encourages sailing to California, circa 1850, courtesy G.F. Nesbitt & Co.

Gold Liberation

Polk’s State of the Union address galvanized the nation, effectively lifting the Eastern Seaboard by its rocky edges to send countless men and women tumbling across the continent. Represented in the rush were people of every race, age and occupation—average men and women seduced by an opportunity that was both factual and mythical, unprecedented and never to be repeated in California’s history.

“They’re hearing stories of guys making three grand in a month,” says McLaughlin. “It was hard for them to believe that California gold was really so abundant, but even harder to believe it would last forever.”

In the northeastern region of cold winters, staid customs and abject economic disparity, California gold magnetized the New England populace more powerfully than can be imagined in our settled twenty-first century culture.

“The economy of the United States was starting to develop and become industrialized, and most people in New England had to work dawn to dusk, six days a week, either in a factory or at a desk,” says Kurutz. “A skilled laborer in New York City was making a dollar or two a day, while the average for prospectors in California was about an ounce of gold a day, or 16 dollars.

“People saw gold as truly liberating,” he adds.

From all over the world, people in pursuit of such newfound freedom descended on California. The melting pot for which the state is celebrated today was made in a pot of gold, into which Europeans, Asians, Australians, and North and South Americans walked, rode and sailed.

Gold was liberating in ways more than just economics. The frigid puritanical values on which New England had been founded dissolved under the warm Pacific sun.

“There was no one to say ‘no’ when you came to California,” Kurutz says. “Your mother wasn’t there, your father wasn’t there, your wife wasn’t there to say, ‘No, you can’t do that.’”

Dozens of ships abandoned in San Francisco Bay during the Gold Rush were dismantled or converted into land structures, photo courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Dozens of ships abandoned in San Francisco Bay during the Gold Rush were dismantled or converted into land structures, photo courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Between 1849 and 1855, roughly 300,000 people arrived in California. San Francisco, a town of only 200 permanent residents when it was still called Yerba Buena, grew to a metropolis of 36,000, among them gamblers, prostitutes, entertainers, sailors, hoteliers, orphans, millionaires and beggars.

And all along the Sierra Nevada foothills west of Lake Tahoe, specifically in the 120-mile-long stretch of gold deposits between Mariposa and Georgetown known as the Mother Lode, an army of prospectors were picking the earth clean. The men and women of the rush swarmed over the foothills in search of their own private treasure, as blind to ecological destruction as they were to the increasingly disenfranchised Native American tribes along the Mother Lode, the population of which was cut down from 150,000 to 30,000 in the 20 years following the start of the California Gold Rush.

“People didn’t care about the environment or the natives at that time,” says Kurutz. “If you’re a young man and you can go make a million dollars tax-free, you’re not going to worry about the little guy. You’re going to get while the getting is good.”

The brevity of the Gold Rush is testament to that reckless mindset. What had taken the earth 40 million years to lay down took humans less than eight years to snatch up.

“The old-timers could very easily mine at the surface, and they did, so a lot of the easy pickings are all mined out,” says Mike Ressel, assistant professor and research economic geologist for the Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology at the University of Nevada. “Those near-surface, high-grade gold resources are pretty much gone.”

Also testament to the thorough, if heedless, gold hunting of those old-timers is the fact that the era ended without a postscript. Outside of the highly destructive practices of hydraulic mining and dredge mining—both of which became illegal in California—no gold renaissance emerged with the advancements of technology and science; no second wave of miners flocked to the sunny West with news of a new Mother Lode.

Elsewhere, yes. The son of a forty-niner inspired the Klondike Gold Rush in Alaska at the turn of the century, and countless operations continue to this day in the less developed regions of Eastern Nevada, Central and Southeast Asia, Australia and South Africa. But the flood of grab-and-go gold prospectors dried to a trickle in 1855, less than a decade after Marshall and Polk broke the dam.

A hydraulic mining operation at Dutch Flat, circa 1863. The highly destructive practice became illegal in California,

photo courtesy Denver Public Library

The Kiss of Death

It wasn’t for lack of trying that California never saw its renaissance. The miners of that era sifted and sampled their way through every river and tributary on the Sierra’s west slope, but by 1855 most were coming up empty. The easy pickings of the Mother Lode were gone, and the miners headed east into present-day Nevada in search of the rumored veins of silver and gold.

There, a few struck it rich, pocketed all the easy pickings, and—as they had done in California—were forced to leave the deeper veins for corporate mining, a lucrative practice that continues in Nevada to this day, earning the mineral-rich state the number four spot in global gold production.

Some persistent prospectors returned to California by way of Tahoe, whose forests were being destroyed to supply timber to shore up the silver mining operations of the lucrative Comstock Lode just 15 miles east in the newly established Nevada Territory.

“The thinking was, ‘If there’s gold on the west slope of the Sierra and also on the east side, maybe there’s some in the Tahoe area,’” says McLaughlin. “It’s called gold rush fever because you really want there to be gold, and you’ll just keep digging and digging.”

For a brief period in the early 1860s, a mini boom struck the Tahoe area based on more hope than evidence. Prospectors picked their way through the rivers, lakes, slopes and summits—and found mineral potential at the entrance to Squaw Valley and in the Martis Valley south of present-day Truckee.

According to McLaughlin, the “theoretical discovery” of gold near North Lake Tahoe was enough to attract a couple thousand gold-seeking explorers, including the prospectors Ward Rush, Hampton Craig Blackwood, John McKinney and Homer Burton, for whom Ward Creek, Blackwood Creek, McKinney Creek and Burton Creek are named.

When the lack of major gold deposits became apparent, the prospectors in Tahoe had two choices: settle down along the shores of the alpine lake or set off for the next theoretical discovery.

“We also had some activity here with the Noonchester gold mine that operated near Homewood before World War II, but nothing ever came of it,” McLaughlin says. “Tahoe is totally distinct geologically from the formations that created gold.”

Gold miners stand in front of the Noonchester Mine just south of Quail Lake near Homewood, circa 1935, photo courtesy North Lake Tahoe Historical Society

Gold miners stand in front of the Noonchester Mine just south of Quail Lake near Homewood, circa 1935, photo courtesy North Lake Tahoe Historical Society

Due to the process of subduction, and the ensuing hydrothermal activity responsible for the creation of gold veins, most mineral-rich deposits are found along fault lines on the flanks of mountain chains, says Ressel.

“Starting about 140 million years ago, the Pacific plate subducted under the North American plate to create a big fault zone. That’s where these Mother Lode veins formed, between the plates,” Ressel says.

Following millions of years of uplift and exposure, some of the gold from the Mother Lode veins eroded and was swept away by the massive rivers that existed in the Eocene Epoch, leaving a trail of shimmering breadcrumbs for forty-niners to eventually trace back to the source.

Unfortunately for gold-seekers in the Tahoe area, that source was generally west of the granite peaks and valleys.

“Granite is the kiss of death for Mother Lode–type gold deposits,” Ressel says. “You want to be on the flank of the granite, not right in it.”

While those same rivers of the Eocene Epoch left a legacy of ancient gravel gold scattered between Donner Pass and the summit of Heavenly, Ressel says the small amount of gold in the Tahoe area likely came from Nevada, which was upstream in the Eocene.

“Those ancient rivers traversed the range before the Sierra Nevada was uplifted,” Ressel says. “That’s how prospectors found bits of river gravel with gold nuggets in them sitting on top of the granite peaks.”

Like all the other surface deposits in California below them, however, those remnants of ancient rivers didn’t stand a chance.

“That was all prospected pretty heavily,” Ressel adds. “Most of the gold-bearing gravels are depleted.”

Finally, the prospectors accepted the truth: California was barren of surface gold. The transient tide surged onward to the next big boom—Nevada, Montana, Alaska—while the rest stayed behind to explore what was increasingly becoming evident: California was a gold mine on many fronts. Those whose identities had been briefly twisted by the rush of gold returned to their roots. Farmers cultivated the valleys, artists flocked to the cities, and men everywhere took what they had stolen from the earth and settled down with their families.

“If you got enough gold to build a house on 40 acres, you’re telling your family to come on out,” says McLaughlin. “You’re not going back to New England.”

And just like that, the rush was over. Most citizens returned to the business of working and eating and living and dying, as if the eight-year period was nothing more than a bout of national insanity.

James Dee works in flooring in Sacramento, but in his free time he can be found panning for gold on the North Fork American River. “I have a job that pays the bills,” he says. “This is all about the search for gold.” Photo by Michael Rohm

James Dee works in flooring in Sacramento, but in his free time he can be found panning for gold on the North Fork American River. “I have a job that pays the bills,” he says. “This is all about the search for gold.” Photo by Michael Rohm

Remnants of the Rush

Today, people still give their lives to prospecting in the Sierra foothills, in defiance of the overwhelming evidence that there is little left to find in California’s once-golden rivers.

“You know, this really is a new gold rush,” says Mike Terronez, continuing in the waning light to pick through the contents of his sluice. “Those old-timers barely even scratched the surface.”

In theory, that is true. Placer mining, by definition, is limited to the sand and gravel in or around bodies of water, through which prospectors can sift with their hands and meager tools. But there remains under the surface of the earth an unknown amount of wealth.

“As much as one hundred million ounces of gold were mined from California between 1849 and the present day,” says Ressel, adding the caveat that the “present day” of large-scale mining in the Mother Lode mostly ended in the 1950s. “There could very possibly be that much left, but it’s hard to say because there is no real exploration for gold deposits here anymore.

“But most geologists know that if you didn’t have constraints to exploration,” he adds, “you’d be in California looking for gold.”

The two main constraints are social and economic. To fully assess the wealth buried in the earth would require new exploration drilling with no guarantees that mining of any discovered resources was feasible.

“California has become a very urban area,” Ressel says. “People, rightly so, want to protect our water and other resources. Mining can be responsible and clean, but societal viewpoints are, ‘We don’t want mining in our backyard.’

“There’s just not a whole lot of impetus for exploration here. There’s more gold to be had, but we’re not headed in that direction. Unless you’re a small-time placer miner, you’re going to go to less developed states or countries that support exploration and mining activities.”

But those small-time placer miners persist.

Right now, two of them are a little drunk and a little stoned, and in the vague light of dusk they have become faded surrogates for an era that ended over a century and a half prior, alive only in the echoes that still resound in those who harbor a fledgling dream—a gold nugget, perhaps. But if that’s too much to ask, then a winding river, a cold beer, a good buddy, and a story that is beautiful, if perhaps fictitious.

Michael Rohm is a freelance writer who lives in the foothills east of Colfax. He is currently attempting to outfit a Chevy Astro van so that he, too, can pursue the siren song of the frontier.

GOLD HISTORY: WHERE TO GO

Marshall Gold Discovery State Historic Park

As the name suggests, this park commemorates the man who kicked off the California Gold Rush of 1849. With his accidental discovery of gold in the South Fork of the American River in 1848, James Marshall inspired one of the greatest voluntary human migrations in history and changed the course of California forever.

Visitors to the park can see a replica of the original sawmill that Marshall was operating at the time, as well as more than 20 historic buildings. There are also opportunities to pan for gold, hike and tour the museum. Be sure to check out the Marshall Monument overlooking the river canyon. It is California’s first historic monument and Marshall’s final resting place.

The park is located in Coloma on Highway 49 between Placerville and Auburn. For more information call (530) 622-3470.

Downieville Museum

What was once a boomtown of more than 5,000 inhabitants during the height of the California Gold Rush is now home to fewer than 500 permanent residents and a small but thriving tourist economy. The historic town sits at the bottom of a canyon between the confluence of the Yuba and Downie Rivers along Highway 49, but the rugged environment that drew prospectors now draws mountain bikers and adventurers.

However, vestiges of the gold rush that once put Downieville in the running for state capitol are still preserved in the Main Street museum. Among the historical artifacts present are pioneer portraits, a to-scale model of turn-of-the-century downtown Downieville, and replicas of gold nuggets pulled from the local Ruby Mine at Goodyear’s Bar.

For more information call (530) 289-3506 or email hangman@jps.net.

David Foote

Posted at 14:29h, 08 MayNice article. Excellent modern and engaging discussion of essential California history studied by every local fourth grade student but perhaps insufficiently appreciated 20, 40 or 60 years later.

Brian McDonough

Posted at 09:21h, 07 JulyI have found the oldest gold mine in North America. It is a Spanish/Mexican gold mine called Minas Sombreros.

There are 3 ancient maps that you can Google that lead to this mine.

The Peralta stones.

The Peralta deerskin map.

The Peralta Burbridge map of 1753.

Yes…that’s right….1753.

This site is easily over 300 years old.

My story was published in Lost Treasure magazine June 2016 cover story…..

The Lost Dutchman gold mine.

It is what Jacob Waltz the Dutchman found 130 years ago that is the epic story.

An ancient Spanish gold mine whose gold according to the legend, went back to Rome, the Vatican, and Spain.

Over 100 people have died in Arizona looking for this place.

Watch Lust for Gold with Glenn Ford and Ida Lupino 1949 on utube. It is about the Peralta mines. Watch the six history channel documentaries called legend of the superstition mountains. It is about the Lost Dutchman Peralta Sombrero gold mines. Watch Leonard Nemoys documentary on “In search of” about the Lost Dutchman.

This is one of the greatest mining stories in the history of North America.

Unfortunately Arizona beaurocrats and pompous politicians are trying to hide my discovery from the public for political reasons. Even after Lost Treasure magazine published my story.

Bummer is….. more people will die trying to find this place. It has been found.

For this state to not tell the public, therefore allowing more people to perish, is quite criminal.

All true. No fiction here.

Brian M.

A gold prospector.

Anyone who can get my story to Ron Howard, George Lucas, or Stephen Spielberg……gets a free tour of the mine.

And a small share of the T”of the Church of Santa Fe”. Google it. There is no story that comes close to this one.

It makes oak island look like a joke.

5 years of a Hollywood documentary series, nothing found.