26 Apr Into Thin Sierra Air

Mt. Whitney tests the mettle of a rag-tag group of hikers with weather, elevation and steep granite

The darkening clouds clustered above us on the shoulders of Mt. Whitney were starting to look angry. It was a bad portent for our eclectic band of eight adventurers.

For one, it cast doubt on whether our goal of bagging the highest summit in the lower 48 states could be accomplished the following morning. Perhaps more troubling, the inclement weather meant the various degrees of preparation in our group would be severely challenged. Earlier, we collected our tents, sleeping bags and assorted necessities and set out at dawn on a cool, clear Friday in early September.

What makes the Sierra Nevada singular among mountain ranges is the cast and quality of its light.

Just ask John Muir. “All the world lies warm in one heart, yet the Sierra seems to get more light than other mountains,” he wrote.

The morning exemplified why Muir wanted to rename the Sierra “The Range of Light”—all blue sky and gold sunbeams as we packed the last of our personal effects and got a jump on the late summer day.

Our group was rag-tag, to be sure.

It was the kind of crew that forms the backbone of those universally liked sports movies. You know the plot—a motley group of seemingly ill-fitting individuals gradually, and through a series of comedic hijinks, coalesce around a common goal, overcome long odds and seize an unlikely triumph. Think Major League in the mountains. Or The Replacements, The Longest Yard, even The Dirty Dozen. You get the idea.

In this instance, the fearless leader of our band was none other than Kyle Magin, the former editor-in-chief of this fair publication.

Since repairing to San Diego for his slice of that good tech money, he and a handful of his cohorts hatched a plan whereby if each of them entered the Mt. Whitney lottery, one was bound to strike permit gold.

It proved a wise gambit, as Tierney, a soft-spoken writer and recent college grad, struck the big one—an overnight camping permit for a Friday night.

She brought along her boyfriend Chris, a welder with an off-color sense of humor. Kelli, a special events organizer at Kyle’s company and the organizer extraordinaire of our excursion, brought along her husband Dan, a lean, athletic and relentlessly positive Midwestern boy from Michigan. Bridget, a brash, ever-laughing, garrulous New Jersey native, rounded out the employees from Kyle’s company. Casey, a barrel-chested San Diego native with a cavernous voice, punctuated our roster.

Then there was me. The fact I was even there was a fluke.

Originally, Mikey, a graphic designer in Kyle’s new outfit, was scheduled to make the trek, but during the gang’s practice run at San Jacinto Mountain outside Palm Springs, the altitude sickened him something fierce and he wisely opted out. After all, Whitney’s biggest challenge is the altitude. It’s the reason that more people fail than succeed when they try to tackle it.

At any rate, I was in.

Going up, photo by Bridget Clerkin

Going up, photo by Bridget Clerkin

The Challenge

Climbing Mt. Whitney is both hard and not hard. It’s 11 miles from the starting point at Whitney Portal to the summit, but because the hike begins at 8,400 feet in elevation, the total climb of 6,100 feet is not as tall as other notable alpine pursuits. What’s more, the elevation gain is spread evenly over the trail, which ascends about 500 feet per mile.

The corollary is that anyone in reasonably good physical condition can tame Whitney.

That said, it’s typically the mountain that does the taming, as roughly 70 percent of summit attempts at Whitney end in failure. A bevy of factors contribute to the high failure rate. Weather, poor physical condition, little to no mountaineering experience, and underestimating the sheer difficulty of the hike all play a role. But perhaps the single most important component is altitude.

Many mountain greenhorns who sally an attempt at 14,505 feet don’t understand the difficulty of strenuous exertion in thin air.

Fit for the Task

Aside from Kyle, Casey and me, there was scant mountaineering experience in our group. And it’s not as though the three of us were giving John Muir a run for his money in terms of logging hours and miles in the Range of Light.

But what we lacked in Sierra backcountry seasoning, we made up for in eagerness, positivity and generally decent physical conditioning. Frankly, the three women—Tierney, Bridget and Kelli—were all in the finest of fettle, but Dan and Chris were right there as well.

Furthermore, aside from Casey and me, everyone was under 35. The wisdom of experience should not underestimate the vigor of youth, as the old saw goes.

After meeting up at the Whitney Portal campground Thursday night, we went lightly on the adult beverages in preparations for the haul the following morning.

At first light, we assembled at Whitney Portal, weighed our packs on the scale provided, closed our eyes as Kelli led us in an invocation and set off in giddy optimism through the forest of manzanita, pine and fir. The first leg of the journey amid the forest’s shadows featured a gentle ascent and a steady stream of ebullient conversation, characteristic of people high on the fumes of adventure who have yet to encounter the challenge of their undertaking.

Soon we reached the first milestone of the Mt. Whitney Trail—a sign that marks the entry into the John Muir Wilderness. For modern hikers, the sign represents the split between the Mt. Whitney Trail and the Mountaineer’s Route—a more direct line to the summit that includes a 1,500-foot ascent up a steep gully with loose rock and a class-three scramble up the final 500 feet. It was first climbed in 1873 by none other than Muir.

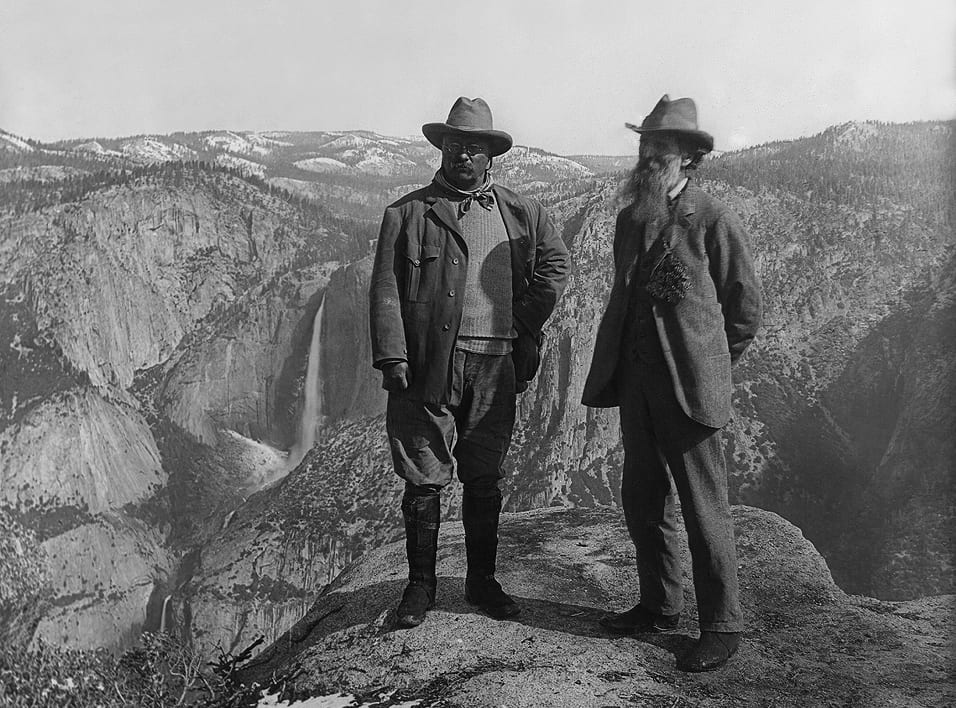

John Muir, right, with Theodore Roosevelt in Yosemite National Park in 1906, courtesy United States Library of Congress

Mountain Pioneers

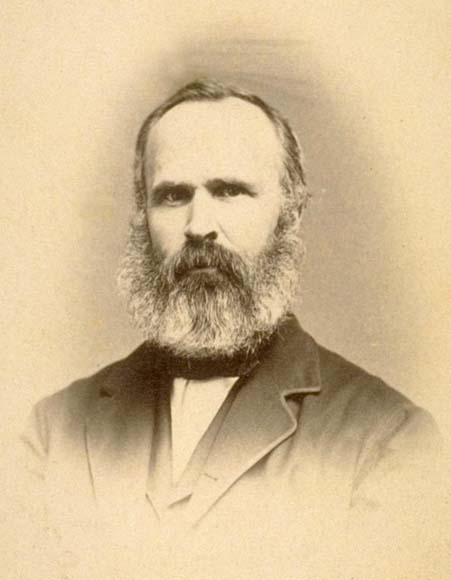

Mt. Whitney is named after Josiah Whitney, a Harvard professor of geology and chief of the United States Geological Survey. In 1860 he became the geologist for the 10-year-old state of California and ordered a survey of the entire territory, including the Sierra.

Mt. Whitney was nearly named Mt. Muir, but John of the Woods was part of the fourth party to scale the summit, and thus too late to qualify for the namesake.

Three fishermen from nearby Lone Pine are credited with Whitney’s first ascent. As the story goes, they were on their way to a trout-filled river in nearby Kern Canyon when they figured they’d bag the highest peak in the Sierra.

Clarence King, one of the first geologists to help conduct the survey ordered by Josiah Whitney, thought he’d captured the first ascent, but he got turned around in a canyon near the top and actually climbed Mt. Langley by mistake. He was part of the third party to climb Mt. Whitney, about a week before Muir pioneered the Mountaineer’s Route in the summer of 1873.

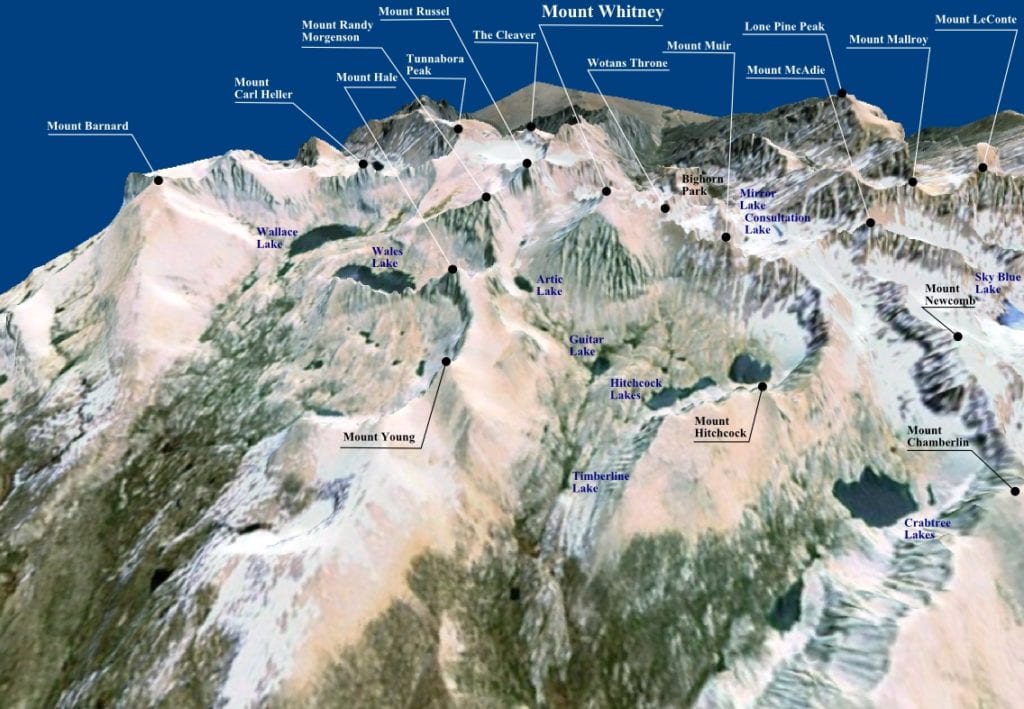

Image courtesy NASA

Image courtesy NASA

Outpost Camp

Soon after passing the threshold of the John Muir Wilderness, our intrepid party arrived at Lone Pine Lake, the first major geographical checkpoint about 2.5 miles in. This also marks the Mt. Whitney permit area, meaning those found hiking without a permit are subject to steep fines.

Forging through late morning sun, we hit the meadows at Outpost Camp around noon. Stopping for lunch next to a Sierra stream running swift and transparent is what wilderness adventures are all about.

We were all swagger and jokes. We’d climbed about 2,000 feet in 4 miles and were only 2 miles from Trial Camp, where we were slated to spend the night before attempting the summit the following day. At the end of the meadow, a 20-foot waterfall fell cleanly over gray granite, spilling a gentle roar over the afternoon repast.

Josiah Whitney

Sierra Rivals

Josiah Whitney didn’t much like John Muir. Perhaps it was personal, but more likely it was a classic case of professional disdain.

By the time Muir climbed Whitney in 1873, he had achieved a modest share of fame, particularly in contemporary scientific circles, for the advancement of a theory that held glaciation was responsible for some of the notable features in the Sierra.

“The Sierra Nevada of California may be regarded as one grand wrinkled sheet of glacial records,” Muir wrote in 1875. “For the scripture of the ancient glaciers cover every rock, mountain and valley of the range.”

Josiah Whitney, on the other hand, held that the granitic valleys of the Sierra were created abruptly by cataclysmic earthquakes, which caused the mountains to separate and the valley floor to plummet thousands of feet in an instant. This view was so widely ascendant that when a large earthquake struck near Lone Pine in March 1872, many settlers residing in the Yosemite Valley fled in fear the temblor was a prelude to another deepening of the valley.

But Muir, convinced of the validity of his scientific theories, blithely roved about the valley collecting samples from newly formed talus piles. His Harvard-educated rival often sneered at the theories of the man he considered his intellectual inferior, calling him an “ignoramus” and a “mere sheepherder.”

Indeed, Muir never finished college. He enrolled in classes at the University of Wisconsin-Madison long enough to learn all he could about botany and geology and then began a long exploratory journey in Ontario, which would eventually lead him to Florida, Cuba, San Francisco and to his cabin in Yosemite.

Today, Muir’s theories of glaciers’ role in the formation of the Sierra are widely held as valid, while Josiah Whitney’s are largely discredited.

The tree line marks the end of shade, photo by Kyle Magin

The tree line marks the end of shade, photo by Kyle Magin

Upward

Past the waterfall and up a couple of switchbacks, our roving band of weekend warriors reached Mirror Lake. A characteristic example of the gin-clear alpine lakes that dapple the Sierra landscape, the lake also marks the end of the shade. Moving on, we encountered granite rock underfoot and a more aggressive slope.

Only a couple miles from the night’s destination, the giddy thrill that propelled us at the start began to wear off and the effects of the altitude materialized. Our pace slowed, our hydration increased and conversation became more sporadic. About a mile above Mirror Lake is the picturesque Trail Side Meadow, with its translucent streams tumbling past melting snowfields. Above the tree line at this point, the lush greenery of the meadows is the only color to offset the vast sea of iron-gray granite spreading upwards to the jagged peaks.

After a brief pause to soak up the scenery, we trundled up the trail to Consultation Lake, a camping destination for some, but only a half-mile away from Trail Camp, where our increasingly weary group of mountain climbers were to rest.

Here, a descending hiker gave us not only the words of encouragement common to passing travelers on the trail, but also some valuable advice. He told us to camp off the lake in a nearby valley, which offered relative seclusion and wind protection. Sure enough, after persisting up to Trail Camp, we veered left and found a gray cleft between two rock walls with a series of developed campsites. In some places, rocks had been piled up against the prevailing direction of the wind, providing modest protection from the sturdy alpine gusts.

This proved indispensable for one member of our party, Bridget, whose sleeping bag was so large that she decided to ditch her tent at the trailhead. She instead brought a rain fly. Using stones, we managed to make a fairly watertight lean-to shelter to provide sanctuary from the elements.

Good thing, too, because about an hour after arriving at Trail Camp, storm clouds gathered and we all dipped into our respective shelters as a mixture of rain, snow and hail fell hard on our site. The lightning and thunder were almost simultaneous, meaning the strikes were close.

Hunting Glaciers

Muir not only pioneered the Mountaineer’s Route on Mt. Whitney, he became the first person to free solo Cathedral Peak in Yosemite four years earlier in 1869. Some rock-climbing historians designate this event as the sport’s advent in North America.

But unlike the scores of mountaineers who ascend Whitney in the present day, Muir wasn’t on a tour. He had a singular focus—proving his theory of glaciation. To be sure, Muir, who wrote some of the most spiritually ecstatic prose about mountain landscapes, took to the high elevations for more than purely scientific reasons.

But one can imagine him bristling when his peers pointed out that a large problem with his glaciation theory was that, unlike the northern Rockies or parts of the Alps, the Sierra Nevada was almost entirely glacier-free. Muir wasn’t convinced. And he had an advantage on his armchair-oriented geological foes: He was willing to climb and explore places others wouldn’t dare go.

“The main cause that has prevented the earlier discovery of Sierra Nevada glaciers is simply the want of explorations in the regions where they occur,” Muir wrote in his seminal book, The Mountains of California.

Muir found more than a few glaciers, documenting as many as 65 during rambles through the high country over four summers. The most famous was the mile-wide Lyell Glacier at the base of Mt. Lyell’s summit—the highest point in Yosemite National Park.

Sadly, many of the glaciers Muir meticulously documented have vanished due to the ravages of a changing climate, while others have diminished to the brink of disappearance.

But not so with Mt. Whitney. When Muir went glacier hunting on the highest peak of his beloved mountain range, he found nary a one.

“Mt. Whitney, although it is the highest mountain in the range, does not now cherish a single glacier,” he wrote. “Small patches of lasting snow and ice occur on its northern slopes, but they are shallow and present no well-marked evidence of glacial motion. Its sides, however, are scored and polished in many places by the action of its ancient glaciers that flowed east and west in tributaries of the great glaciers that once filled the valleys of the Kern and Owens rivers.”

No Sleep Till Whitney

Turning in early meant we were better served to wake up at 3 a.m. and bag the peak before heading down. It was 5 miles to the top and, along with an 11-mile descent back to Whitney Portal, our merry band had a bear of a day in front of us.

Sleep was imperative.

But it was not my lot to experience what Muir called “the clear death-like sleep that always comes to the tired mountaineer.”

The main reason we stayed at Trail Camp was to give ourselves an opportunity to acclimate to the altitude overnight. A good night’s sleep at 12,000 feet should put you in good stead for knocking out the remaining 2,505 feet the following day. Theoretically.

I couldn’t sleep because I couldn’t catch my breath. I woke up short of breath several times. A little panicked, I’d sit up, unzip my tent and gulp in the fresh air until my heart stopped racing enough to attempt another round of shuteye. The steady snores of my cohorts convinced me I was the only one wrestling with the altitude. I resigned myself to telling everyone first thing that the altitude was too much for me and I wished them luck but I was headed down. But when we all roused ourselves early in the morning, there were enough tales of little to no sleep and trouble breathing that I kept quiet and prepared for the ascent. Sometimes peer pressure is a blessing.

The nice thing about an overnight is the heavy pack full of equipment could be left at the tent site. I packed a much lighter bag with a snack and enough water to see me through to the top.

I drank a little Acli-Mate to help with the altitude, and off we went up the 99 switchbacks.

Morning in the Range of Light, photo by Kyle Magin

Morning in the Range of Light, photo by Kyle Magin

Danger by Switchback

Perhaps the most iconic part of the Mt. Whitney Trail, the 99 switchbacks, begin right after Trail Camp and rise 1,700 feet into the truly rarified air of the High Sierra.

We got started later than we intended, largely due to indecision related to trail conditions, which Kyle expected to be dangerous as a result of the copious amounts of precipitation and overnight freezing temperatures.

We disembarked from camp around 5 a.m. despite our leader’s trepidation, which, in the end, turned out to be acutely understated.

Conditions were extremely dangerous.

Verglas is a thin, clear sheet of ice formed due to the freezing of rain or meltwater on a hard, smooth surface, like rock. It was all over the trail. In some of the switchback pivots, the ice was skating rink thick and impossible to avoid. Only careful, methodical foot placement saved us from slipping.

And with the precipitous cliffs off the side of the trail, any slip would likely prove fatal, particularly toward the top of the climb. Perhaps because it was dark for most of the ascent, we didn’t realize the extent of the exposure and the high stakes of placing each foot correctly. By now the conversation from the previous day had vanished. All of us were intent on the trail.

Casey assumed the head of the group as both his pace and capacity to call out icy spots were heavily relied upon. Those warnings were relayed back, with Kyle bringing up the rear to monitor the progress in front of him.

What Bridget lacked in preparation, she made up for in fitness, athleticism and overall positive outlook. Tierney and Chris steadily gobbled up the terrain, while Kelli faltered only slightly at the top. But after a brief pep talk from Dan, she took her position right behind Casey and bent her will toward the summit.

Icy conditions make for dicey footing on the 99 switchbacks, photo by Bridget Clerkin

Icy conditions make for dicey footing on the 99 switchbacks, photo by Bridget Clerkin

Trail Crest

Upon arriving at the top of the 99 switchbacks, about 2 miles separate the beginning of the Trail Crest and the pinnacle of the helmet-shaped peak of Mt. Whitney. At 13,600 feet, most of the climbing is behind you, although that final 900 feet takes you into truly thin air.

Although I was anxious about altitude sickness, I barely noticed being short of breath because of the intense concentration required by a trail covered in slippery snow and ice.

On parts of Trail Crest, our team had to crab-walk due to the conditions and steep consequences of falling. But another distraction was the scenery. The wide panoramas into the Owens Valley and across into the White Mountains are spectacular, particularly when accompanied by the mellow hues of encroaching dawn.

Westward, the serrated spine of the High Sierra spreads out in all directions, with snow-flanked pyramids jutting into that crystalline blue of mountain skies hemming in Guitar and Hitchcock lakes, located off the western shoulder of Whitney in Sequoia National Park.

If trying to confront a fear of heights, Trail Crest affords plenty of opportunities. In between jagged peaks along the trail, there are “windows” to the east, presenting dizzying descents back the way we came and making for some heady moments as we steadied on through the morning.

Parties heading back our way after summiting earlier in the morning provided another welcome distraction. Distance estimates, trail condition updates and general words of encouragement were generously handed out, and it was a favor we tried to return on our way out.

Despite Whitney’s reputation as intolerably crowded, we found that it was really not that bad. And, there is a comforting sense of solidarity among the hikers lumbering to and from the peak.

Giant views open from the flanks of Mt. Whitney, photo by Kyle Magin

Giant views open from the flanks of Mt. Whitney, photo by Kyle Magin

The Final Push

After a straight stretch, including a narrow path through a semi-permanent snowfield, there was just one more rolling ascent through a landscape of pale talus.

The last pitch is more like walking up a dome than an isosceles peak, and we reached the iconic Summit House around 10 a.m. with nothing left to do but sign our names in the guestbook, give a few high-fives, pose for some photos and soak in the crowning views of the High Sierra.

Although the weather can turn quickly and the wind stings the skin, you don’t want to leave too quickly after working that hard to get there. And with all the fanfare, you’ll want to reserve a quiet moment for yourself to convene with all that mountaintops have to offer.

Like John of the Woods wrote, “Climb the mountains and get their good tidings. Nature’s peace will flow into you as sunshine flows into trees. The winds will blow their own freshness into you, and the storms their energy, while cares will drop off like autumn leaves.”

We accomplished our mission. And while undoubtedly arduous, the message of this particular Whitney ascent is that if I can do it—if our motley crew can do it—anyone can.

Matthew Renda is a Santa Cruz–based writer and former Tahoe resident. He considered using a Segway to summit Mt. Whitney but resorted to hiking when shamed by his fellow group members.

Group members are all smiles after reaching the summit. From left, Casey Fox (front), Bridget Clerkin, author Matthew Renda, Tierney Brannigan, Dan Stevenson, Kelli Jensen, Kyle Magin and Chris Anderson, photo courtesy Kelli Jensen

Group members are all smiles after reaching the summit. From left, Casey Fox (front), Bridget Clerkin, author Matthew Renda, Tierney Brannigan, Dan Stevenson, Kelli Jensen, Kyle Magin and Chris Anderson, photo courtesy Kelli Jensen

Kelli Jensen

Posted at 21:20h, 02 MayMatthew Renda, you captured the essence of our journey so perfectly, I felt like I was climbing all over again. What a beautiful way to educate readers on the history, and share the weakness and triumph we experienced and achieved! Thank you!

Casey Fox

Posted at 22:45h, 02 MayYeeeeeewww, rad article! Get “hi”…go hiking!

Reggie S Beaufore

Posted at 16:12h, 04 MayAs Kyle’s mom I am so proud of him and so very glad I didn’t understand or appreciate the danger in this adventure.