01 May A New Approach to Tahoe Clarity

Scientists are studying the impacts of removing non-native mysid shrimp from Lake Tahoe’s famously clear waters

Replacing one tiny critter that doesn’t belong in Lake Tahoe’s waters with an even smaller one that does could offer promising possibilities when it comes to restoring the lake’s threatened clarity.

At iconic Emerald Bay, scientists are studying ways to reduce the abundance of mysid shrimp, which were introduced into the lake as fish food decades ago with unintended and damaging consequences.

Reducing populations of those shrimp, experts believe, could encourage the return of smaller zooplankton to Lake Tahoe in healthy populations. The native zooplankton graze aggressively on algae, one of the key contributors to the lake’s clarity loss over the last 50 years.

If successful, the effort might demonstrate an important new approach to address Tahoe’s clarity problems, particularly in the face of changes associated with a warming climate.

“It does show a lot of promise,” says Brant Allen, staff research associate with the UC Davis Tahoe Environmental Research Center and captain of the Tahoe research vessel John Le Conte, used in a 2018 pilot project to haul shrimp from Emerald Bay’s waters by net.

“We’ve spent somewhere around $1 billion in the Tahoe Basin working to improve water clarity, and a lot of good work has been done, but that money was all spent on landscape restoration,” Allen says. “What we’ve found shows huge promise for aquatic ecology restoration that could result in dramatic increases in clarity.”

Mysid shrimp were introduced to Lake Tahoe from the Great Lakes between 1963 and 1965, intended to provide food for both Mackinaw and Kokanee, photo courtesy UC Davis

Consequential

Fish Food

The mysid (alternately known as mysis) shrimp story dates back to a three-year period between 1963 and 1965, when wildlife officials from California and Nevada introduced the small crustaceans into Lake Tahoe with the idea of providing a new food source for two non-native game fish: Mackinaw (also called lake trout), introduced by humans in the 1880s, and Kokanee salmon, brought here in the 1940s.

While mysid has provided a successful food source for game fish in other lakes across the country, it did not succeed to the same degree at Tahoe. That’s because Tahoe’s waters are so clear that during the day, the shrimp swim as deep as 1,000 feet to escape harmful rays from the sun—below where the targeted fish swim and feed.

But mysid’s presence at Lake Tahoe came with serious consequences. They fed voraciously on native zooplankton, leading to the near extirpation of the zooplankton Daphnia and resulting in what UC Davis scientists describe as a “dramatic change in the makeup of the Lake Tahoe zooplankton food web.”

Because zooplankton graze on algae, major reductions in their numbers allow algae to flourish. Combined with fine sediments washing into the lake from Tahoe’s roads and urban areas, algae growth is believed to be responsible for alarming drops in clarity measured in recent decades.

The research vessel John Le Conte pulls a mysid trawl through the waters of Lake Tahoe, photo courtesy U.C. Davis

A Clear Correlation

In 1968, one could see more than 100 feet into Tahoe’s depths. Now, average clarity is around 70 feet despite decades of work to control polluting runoff and restore natural wetlands to filter sediments, among other improvements. While the loss in clarity appears to have stabilized, the problem remains of serious concern.

In 2011, and after a 26-year gap in Tahoe’s measured mysid population, the Tahoe Environmental Research Center began gauging shrimp densities around the lake. While populations across most of Tahoe were consistent with past surveys, researchers were surprised to find that for whatever reason—and they’re still not sure why—shrimp numbers in Emerald Bay had dropped dramatically.

Two other things were then documented: Native zooplankton quickly returned to Emerald Bay in healthy numbers, and water clarity improved dramatically, apparently as a result.

“Within a short period of time we saw the zooplankton rebound and become very abundant,” Allen says. “Shortly after that we noticed the water clarity doubled in Emerald Bay.

“Emerald Bay’s clarity actually exceeded Tahoe’s, which is very unusual. Essentially, the ecology in Emerald Bay rapidly returned to what it was pre-1965.”

By late 2013, mysid numbers in Emerald Bay started to rise again, with a corresponding drop in the zooplankton population and water clarity. The events captured the close attention of researchers, who begged the question: Could humans improve lake clarity by somehow deliberately reducing the mysid shrimp population?

“The goal was to see if we could successfully remove mysid shrimp,” says Geoff Schladow, executive director of the Tahoe research center. “Rather than let nature do this, can we help it along?”

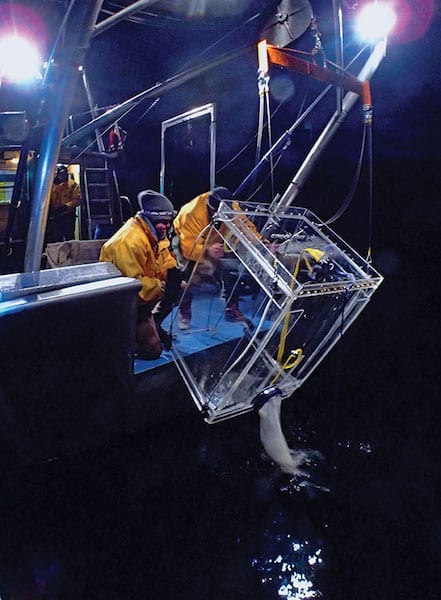

Researchers recover a Schindler trap used to quantify shrimp populations in the water column

Removal Efforts

What followed was an investigation to answer that question. In a $450,000 pilot project funded by the California Tahoe Conservancy and Nevada Department of Environmental Protection, scientists attempted to figure out if shrimp could effectively be removed from Emerald Bay through the use of a trawling net towed by the research vessel John Le Conte.

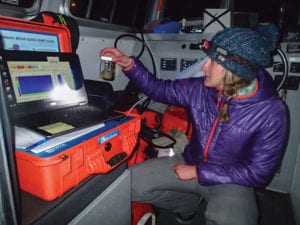

Cutting-edge technology was employed, including use of a hydroacoustic sounding device mounted on the boat that could measure population density and three-dimensional distribution of the shrimp, and record behavioral patterns. Detailed surveys were conducted across Emerald Bay, as well as off of Camp Richardson and between Tahoe City and Deadman Point.

Actual removal of the shrimp proved tricky. Researchers borrowed a specialized trawling net from Florida International University in Miami, but the device wasn’t quite up to the task. After trawling in Emerald Bay commenced in February 2018, scientists quickly discovered the net’s mesh was too large to successfully capture a sufficient number of the mysids, which are between a quarter-inch and half-inch in size when mature. It took months of modification before the necessary tool was produced.

Work began in earnest the following fall. And it wasn’t easy, says Allen.

Trawling could only occur at night, when conflict with any other boaters wasn’t likely and, more importantly, at a time when the shrimp rise from the depths and swim close to the surface. It occurred during the dead of winter, often in single-digit temperatures. Ice covered the vessel’s decks. Gloves stuck to metal. Simply put, it was miserable.

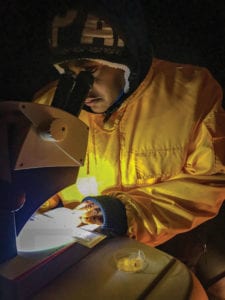

Siya Phillips measures mysid shrimp captured in a trawl during night work in Emerald Bay, photo courtesy UC Davis

“It was a lot of work under some very unpleasant conditions,” Allen says. “It was kind of a modest version of Deadliest Catch at Tahoe.”

The efforts proved successful, however. “We started catching a lot of shrimp, which was great,” Allen says.

Between late October and mid-December 2018, researchers harvested some 330 pounds of shrimp—an estimated 3.3 million of the tiny crustaceans in all. They measured a 19 percent reduction in Emerald Bay shrimp density between November and December 2018. Researchers acknowledge factors other than the trawling harvest could have contributed to that drop and say more research and monitoring will be needed to truly determine the effectiveness of the effort.

“We don’t yet know if the pilot project will be able to be considered successful,” says Jason Kuchnicki, supervisor of the Lake Tahoe Watershed Program for the Nevada Department of Environmental Protection, which provided $60,000 toward the project.

Researcher Katie Senft studies a mysid sample while tracking the shrimp population using a scientific echo sounder, photo courtesy UC Davis

Optimizing harvest methods will be the focus of additional work occurring in 2019, Kuchnicki says.

Long-standing goals to reduce the amount of fine sediment washing into the lake—the other major factor when it comes to recorded clarity loss—must remain an ongoing emphasis, experts agree.

But as a warming climate appears to make algae an increasing danger for Lake Tahoe’s clarity, particularly during the summer months and in shallow depths, “this could be a very important mechanism” in the future, Kuchnicki says.

“With climate change we’re going to have to relook at what measures might be effective as opposed to others,” says Patrick Wright, executive director of the California Tahoe Conservancy, the project’s primary sponsor. The conservancy awarded a $390,000 grant in September 2017 to finance the Emerald Bay endeavor.

“It’s clear we’re going to need some new ideas and approaches,” Wright says. “We’re going to learn a lot from this. That’s really the key: to increase our understanding.”

A Shift in Thinking

Trawling for shrimp in the confines of Emerald Bay is one thing. Expanding the effort across the lake—should it be determined that shrimp removal makes sense on a larger scale—would be something else entirely, with assistance needed outside of university researchers.

“If it could be scaled up, it would have to be something of a commercial operation,” Schladow says.

The shrimp—rich in Omega 3 fatty acids—could conceivably be marketed as a dietary supplement for humans or as a high-quality pet food, Schladow says.

As for how Tahoe’s shrimp could be harvested on a large scale, one possibility is a fleet of autonomous trawlers working at night.

“One could think of a small fleet of driverless electric trawlers. Nobody sees them. Nobody hears them. It’s something that could happen under the cover of darkness,” Schladow says.

Another possibility is the use of submerged ultraviolet lights to kill the mysids with radiation, though the dead shrimp would sink into Tahoe’s abyss and not be available for commercial gain.

Whatever happens, Schladow says the project is important because it represents a significant shift in thinking regarding the future of a national treasure.

“This is probably the first major clarity project that is targeting the ecology for returning Lake Tahoe to its previous ecosystem state,” Schladow says. “This one is saying, ‘How can we work with the lake’s own ecosystem processes to undo the mistakes of the past?’”

Jeff DeLong is a freelance writer based in Incline Village.

No Comments