23 Apr An Oasis of History High in the Hills

Glen Alpine Springs at the edge of Desolation Wilderness retains its rustic charm a century after the resort’s bustling heyday

Built in 1889, this barn at Glen Alpine Springs is still in good condition and houses tools, horse stalls and a hay loft, photo by Martin Gollery

Each summer, thousands of eager hikers flock to Desolation Wilderness, focused on reaching the area’s sparkling lakes and granite peaks. But along one of the most popular trails into the wilderness, they stumble upon an unexpectedly rich part of Tahoe’s history—a bubbling spring and a group of buildings designed by one of the nation’s preeminent architects.

Glen Alpine Springs is a surreal trip back into Tahoe’s early tourism and ranching history, and a fascinating look into the lives of the Tahoe visionaries who shaped this important corner of the lake.

Beginning near Fallen Leaf Lake, the Glen Alpine Trail passes several old cabins on a gravel road before reaching a sturdy barn built in 1889. Beyond, the trail reaches a small well where gently bubbling water rises up below a sign marked “Soda Spring.” Next to the spring sits a charming old building made of rock, glass and metal, once the assembly hall for the sprawling Glen Alpine Springs resort established in 1878.

The resort’s founder, Nathan Gilmore, was a true visionary whose legacy includes the creation of the trails and the gifting of the land that became Desolation Wilderness. Several fascinating buildings at the resort that still stand were designed by Bernard Maybeck, considered one of the top architects in American history.

At its height in the early 1900s, the Glen Alpine Springs resort consisted of 25 buildings, including a 16-room hotel. Five of the nine buildings on the property today were designed in the 1920s by Maybeck, a frequent visitor who was chosen after a fire destroyed several buildings on the property in 1921.

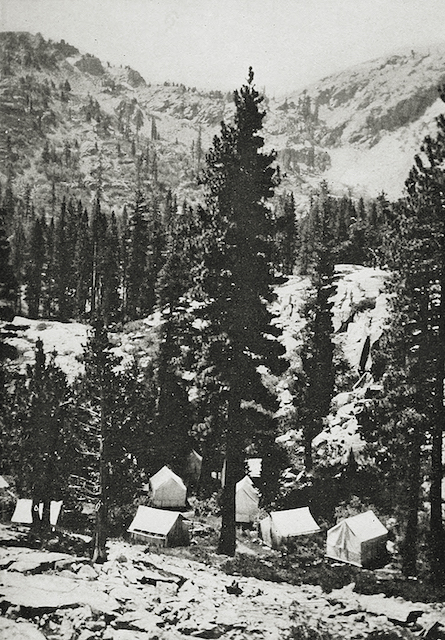

Glen Alpine Springs tent cabins nestled under towering pines ae pictured in 1915, courtesy photo

Gilmore Comes for Gold

Gilmore came to California from Ohio in 1850. He panned for gold, opened a store and was running a small cattle operation in 1863 when he discovered the soda spring, which would later become the centerpiece of the resort.

One historian says it took Gilmore and his family six days to bring his herd of cattle from the valley over what would become Echo Summit to the lush meadows around Fallen Leaf Lake. They started with 74 head but lost 20 on the treacherous journey. One morning while following some errant cattle, Gilmore discovered them at the mineral spring.

“To his surprise, he saw that they had been drinking at a mineral spring bubbling from the rocks,” writes E.B. Scott in The Saga of Lake Tahoe. “Convinced by his first taste that the water was both fresh and palatable, Nathan Gilmore and his drivers returned to the shore of Fallen Leaf to move his family and their camp up canyon to the springs.”

In 1871 Gilmore filed a homestead deed for 10,000 acres of land that extended from near Fallen Leaf Lake into the heart of what was then known as Devil’s Basin (now Desolation Wilderness) and began developing the resort.

The name Glen Alpine Springs was inspired by Sir Walter Scott’s lengthy 1810 poem The Lady of the Lake, which was a favorite of Gilmore’s wife, Amanda Gray Gilmore, according to legend. Upon her death in 1880, Gilmore named the resort Glen Alpine.

A Spring Attracts Celebrities

Glen Alpine Springs founder Nathan Gilmore encouraged visitors to drink the water from this mineral spring, which he marketed as an elixir, photo by Jaime Lyn Pirozzi, courtesy Local Freshies LLC/LocalFreshies.com

Gilmore marketed his property as a health resort, encouraging visitors to imbibe the sparkling soda water that bubbles up to the surface as an elixir. As Glen Alpine Springs Resort grew, he added more cabins and developed nature trails into the wilderness to entice visitors. He also stocked the creeks and lakes with trout, raised Angora goats for wool, and bottled and sold the spring water.

In an early use of celebrity for marketing purposes, Gilmore brought Polish actress Helena Modjeska to the resort in 1878 to entertain the guests. In her honor her fans named the waterfall near the resort Modjeska Falls. The resort experience was also enhanced by Susie Jackson, a member of the Washoe Tribe who taught basket weaving and sold her baskets at Glen Alpine Springs during the early years.

Guests stayed in “hospitable cottages, log houses and spacious tents,” writes George Wharton James in his 1915 book Lake of the Sky. James enjoyed the rustic, down-to-earth charm of Glen Alpine Springs compared to other resorts in the area that he felt were snooty. Later a small hotel was built, and by the late 1920s guests dined on three meals a day served on linen and china in the unique dining room designed by Maybeck.

In the early years, guests stayed for long periods of time simply because it was a grueling journey to get there. Most visitors took a train to Truckee and then another train along the Truckee River to Tahoe City. From there, launching from the Tahoe Tavern Resort pier, they crossed the lake via steamboat, followed by a horse-drawn stagecoach over the narrow, rugged road along Fallen Leaf Lake to the resort.

Acclaimed architect Bernard Maybeck designed a number of buildings at Glen Alpine Springs using locally sourced, fireproof materials, including the assembly hall pictured here, photo by Jaime Lyn Pirozzi, courtesy Local Freshies LLC/LocalFreshies.com

A Legacy of Conservation

In 1898 Gilmore’s daughter, Susie, married George W. Pierce at the springs. Upon Gilmore’s death the same year, she began a long period of managing the resort, assisted later by her son, Dixwell Pierce, who also married at Glen Alpine Springs in 1926.

By World War I, with the expanded use of the automobile and better roads, visitors could reach the resort in less time, and they began to stay for shorter periods. As Lake Tahoe became a bigger tourist attraction over the ensuing decades, fewer and fewer people visited the relatively remote Glen Alpine Springs. By the time the Olympics were held at Squaw Valley in 1960, the resort was on its last legs, and it closed in 1966.

This rustic cabin is still used by volunteers during the summer months, photo by Jaime Lyn Pirozzi, courtesy Local Freshies LLC/LocalFreshies.com

While it is no longer a running resort, Glen Alpine Springs has an important legacy. When John Muir visited in 1892, he came with the presidents of UC Berkeley and Stanford University, who met with Gilmore and formed the Sierra Club. Muir fell in love with the resort, saying, “It seems to me it’s one of the most delightful places in all the famous Tahoe region.”

Not only was Gilmore part of the team that lobbied President William McKinley to establish the Lake Tahoe Forest Preserve in 1899, he made the wilderness a possibility by relinquishing his claim to the land that would become Desolation Wilderness, one of America’s most popular wilderness areas.

Gilmore sought to protect the land for future generations while also shielding it from the ambitions of Lucky Baldwin, who wanted to expand his holdings beyond his Baldwin Hotel on nearby Lake Tahoe to include the lakes that are now part of Desolation Wilderness.

Warren Olney from the newly formed Sierra Club wrote at the time, “Everybody is interested in preserving the property for the use of the public on one side, against a private speculator (Baldwin) on the other.”

Today, several features in the area are named in honor of Gilmore and his family, including Gilmore and Susie lakes in Desolation Wilderness (although the latter may have also been named after Susie Jackson, the Washoe woman who spent a lot of time at the resort). Angora Lakes, Ridge and Peak were named after the Angora goats that Gilmore raised on the property, while his fellow trail builder, Barton Richardson, is the namesake of the small lake just north of the Desolation Wilderness boundary, Richardson Lake.

Gilmore’s property was sold in 1978 by Robert Fritschi to the US Forest Service under a life estate, which means Fritschi will maintain possession of the property until his death, at which time the Forest Service will take full possession.

The Historical Preservation of Glen Alpine Springs maintains the remaining buildings at the resort and provides educational experiences to the public during the summer months, photo by Jaime Lyn Pirozzi, courtesy Local Freshies LLC/LocalFreshies.com

Now, the nonprofit Historical Preservation of Glen Alpine Springs maintains the remnants of the resort, providing educational experiences to the public in the summer months.

“Our goal is to preserve the whole area and bring more families to experience the resort,” says Cody Tice, executive officer of Glen Alpine Springs.

In addition to the key goal of maintaining the Maybeck-designed buildings and other property assets, Tice says the organization hopes to eventually reopen the dining facilities and host dinners. He would also like to see restroom facilities constructed at the resort and allow the public to regularly sample drinks concocted directly from the spring.

Next time you hike into Desolation on the Glen Alpine Trail, be sure to allow enough time to explore Glen Alpine Springs. Begin your exploration with a review of the interpretive panels next to the trail, then wander uphill past the rustic cabins and the uniquely constructed Bubble Building to view the Maybeck-designed dining hall and kitchen facilities. There, take a deep breath, shut your eyes and take a virtual step back in time 95 years, envisioning the place bustling with escapees from city life who made the long journey to enjoy the sights, sounds and smells of the Sierra Nevada. In other words, the same reason people visit the Sierra today.

Tim Hauserman is a freelance writer based in Tahoe City. After hiking past Glen Alpine Springs dozens of times over the years, he finally decided this past fall that he needed to learn the story of its history.

Maybeck’s Palace of Fine Arts in San Francisco, photo courtesy Library of Congress

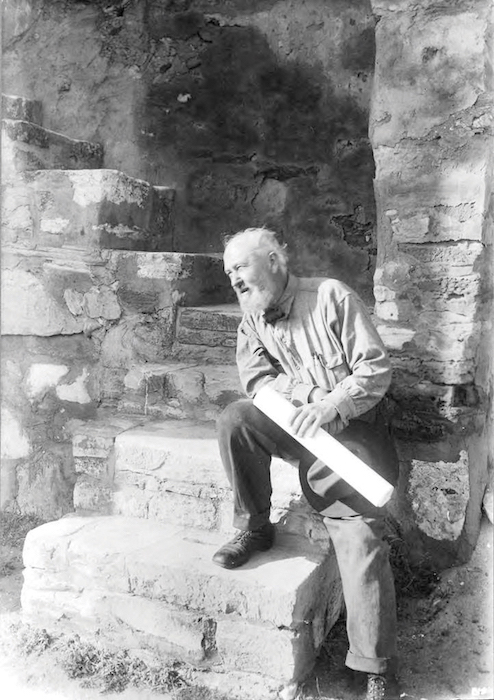

Bernard Maybeck in 1919, photo courtesy L.S. Slevin

The Story of Maybeck

Bernard Maybeck came to California in 1850, working as a professor at UC Berkeley before opening his design business in San Francisco. His masterpiece is considered the First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Berkeley, although the Palace of Fine Arts in San Francisco is perhaps his best-known work.

Maybeck was designated by the American Institute of Architects as one of America’s top 10 architects. Three of his designs are National Historic Landmarks, and six others are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Maybeck enjoyed spending time in the summer at Glen Alpine Springs with his wife, Anne, and their two children. He exchanged his design services for the right to stay there.

His 1921 dining room and kitchen used battered stone piers constructed without mortar, large windows and industrial steel. They have concrete floors and the timbers are covered in metal—all designed to prevent another fire like the one that destroyed a portion of the resort in 1921. He also designed the assembly hall next to the soda spring in a similar glass, metal and stone ambiance, and the Bubble Building, which employed the first use of lightweight aerated concrete in the United States.

The combination of metal, rock and glass that Maybeck used so successfully at Glen Alpine Springs can be found in many of the high-end homes constructed around Tahoe today.

No Comments