23 Apr Baking in Basque Tradition

A nearly century-old brick-and-stone oven on former sheepherding land serves up historic culinary experiences

If you’re going to eat food from a Basque oven, bring wine.

Tell a friend to bring her guitar. It wouldn’t be in the Basque tradition to cook here without drink and song. Plus, you’re gonna wait a while.

Ian Baker tends to a pizza cooking in the Basque oven, photo by Lauren Shearer

The tall, beehive-shaped brick-and-stone ovens take hours to heat up with burning logs. Ian Baker, a greenhouse manager and talented amateur chef out of Alta, California, is something of a specialist.

“Managing a brick oven is an art,” Baker says. “You have to get out by 6 or 7 (a.m.) to get it going by noon.”

Wood logs are lit inside the oven to heat it up to 700 to 900 degrees. Once the wood burns down, the coals are swept off the oven’s stone floor, at which point the super-heated surface is used to cook.

Baker hosts summer cookouts at the Basque oven located at Wheeler Sheep Camp in Kyburz Flat, a plot of Tahoe National Forest land about 25 minutes north of Truckee on State Route 89.

He serves a menu that has fluctuated over the years, including pizza, leg of lamb, pork belly and, of course, bread.

Bread is the tie that binds the people who use the Kyburz Flat oven to its past. It’s a past that has informed the way people in the Sierra eat, drink and live.

The general public can reserve the oven for group cookouts, photo by Lauren Shearer

Killing Time

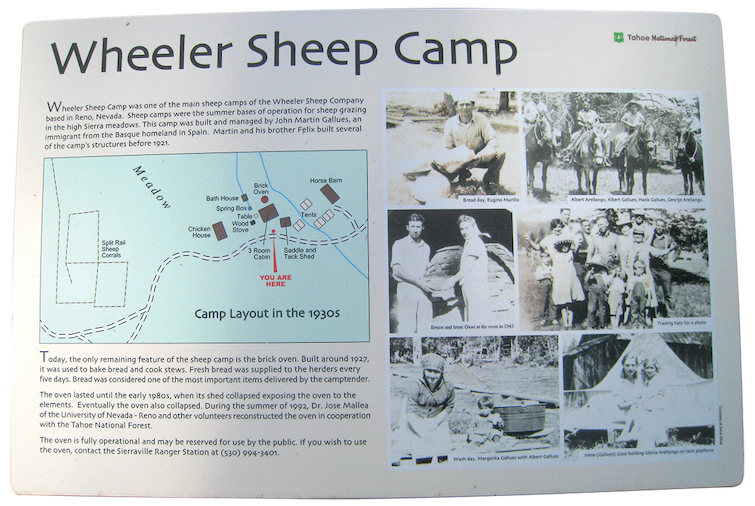

A pair of Basque sheepherders—brothers Martin and Felix Gallues—constructed the first Kyburz Flat oven in 1927, according to a National Forest Service report. They were shepherding for Nevada rancher Dan Wheeler at the time.

The Gallueses built it in the style of bread ovens found on the second stories of home in their native Basque country in Northern Spain, says Dr. Xabier Irujo, director of the Center for Basque Studies at the University of Nevada, Reno (UNR). They may have been looking for something to do besides watch sheep eat grass, he says.

“It takes a long time to produce bread, and that may be why these people brought it here,” Irujo says. “They needed something to do. Otherwise shepherding can become very boring.”

An interpretive sign outlines the history of the Wheeler Sheep Camp in Kyburz Flat, photo by Lauren Shearer

Basques in the West

The Gallues brothers, despite having lived in the area nearly a century ago, fall in a pretty recent point on the timeline of Basque people in the Americas, Irujo points out.

Basque immigrants were among the first Europeans to land in the Americas in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, serving as governors in New Spain (modern-day Mexico) for the Castillian (Spanish) Empire.

Successive waves came to the Americas in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, populating everywhere from Canada to the Caribbean to Argentina. They began populating the American West in heavy numbers in the mid-nineteenth century as the Gold Rush intensified.

Around that time, Basques began working as shepherds. Though they held all sorts of jobs in the old country—many were sailors—Basques began herding sheep because the work was available, Irujo says. Like immigrants before them, once one person became established, he’d send for family to follow him to the United States, just like the Gallues family.

“For most people, when they speak about Basques, they think about shepherds,” Irujo says. “But one of the first institutions Basques organized here were schools for English. By the second generation, Basques had moved out of herding.”

True to form, Martin Gallues was the last of his family to work the Wheeler Sheep Camp—he retired in 1955, roughly a decade after his sons returned from World War II to one of the “most memorable celebrations” the camp ever hosted, according to the Forest Service report.

Basques then moved into the business of restaurants, hotels and politics. Reno’s Santa Fe Hotel restaurant is one such example of a Basque boarding house turned hotel and bar, as well as the Star Hotel in Elko, Nevada. Both serve Basque-American entrees like chorizo burgers and lamb alongside Nevada’s state cocktail, the Picon Punch, a boozy Basque country concoction.

Lawmakers including California U.S. Representative John Garamendi (D-Davis), and members of Nevada’s Laxalt family—among them Paul Laxalt, the state’s former Republican governor and U.S. Senator—hail from Basque origins.

Rebuilding History

While younger generations of Basques turned toward new careers, a hunger grew to preserve their cultural heritage, Irujo says.

“They were losing their roots,” he says of Basque descendants. “So this is the origin of Basque centers and Basque cultural activities, like organizing dances.”

UNR’s Center for Basque Studies opened in 1967 (though it was originally affiliated with the Great Basin Institute). In 1992, volunteers and members of the program, under the direction of former director and Basque history author Joxe Mallea, rebuilt the brick oven at Kyburz Flat. Word soon got around among local foodies and Basque descendants, who brought celebrations back to the forest’s edge alongside a meadow that used to belong to the Wheeler herds.

The wood-burning Basque oven is heated to around 450 degrees, photo by Ian Baker

“An old roommate of mine in Truckee [where Baker lived between 2005 and 2009] had talked to me about this oven for a long time,” Baker says. “He had this idea to get out there, but we just never got around to it. I have this habit of adventuring, so a few years later I decided to do what he proposed. The first time I went there for myself, I knew that this was a magical place.”

“[Basques] really left their mark on the forest as far as cultural sites,” says Erica Jaeger, the East Zone archaeologist for the Tahoe National Forest. Jaeger oversees the site’s upkeep, which amounts mainly to adding new mortar between the bricks every other year, she says.

The general public can reserve the oven for free by calling the Sierraville Ranger Station at (530) 994-3401. The site is available throughout the summer beginning in June, Jaeger says.

Booking the site can sweep you into history. If you visit, be sure to make a toast to Martin Gallues and the Basque immigrants like him who contributed to the American West and this corner of the Sierra.

Former Tahoe Quarterly editor Kyle Magin is a writer and editor based in Austin, Texas. He’s glad to eat bread and drink wine with anyone who wants to wake up at 6 a.m. to start the oven.

Sheepherder’s Bread

Ingredients:

3 cups very hot tap water

1/2 cup butter, margarine or shortening

1/2 cup sugar

2 1/2 tsp salt

2 packages active dry yeast

About 9 1/2 cups all-purpose flour, unsifted

Light-flavored vegetable oil

Directions:

In a bowl, combine water, butter, sugar and salt. Stir until butter melts and cool to 110 to 115 degrees. Stir in yeast, cover and set in warm place until bubbly, about 15 minutes.

Add 5 cups flour and beat to form thick batter. Stir in enough of remaining flour (about 3 1/2 cups) to form stiff dough. Turn out on floured board and knead until smooth and elastic (about 10 minutes), adding flour as needed to prevent sticking. Turn dough into greased bowl, cover and let rise in warm place until doubled, about 1 1/2 hours. Punch down and knead to form a smooth ball.

Grease inside of Dutch oven and inside of lid with vegetable oil. Place dough in Dutch oven and cover with lid to let rise for the third time. Let rise in a warm place until dough pushes up lid about 1/2 inch (watch closely).

Bake covered with lid in 375-degree oven for 12 minutes, carefully remove lid and bake for another 30 to 35 minutes, or until loaf is golden brown and sounds hollow when tapped. Remove from oven and turn out on rack to cool.

Felis Gallues

Posted at 07:44h, 09 JuneGreat story! My family built this, but the last name is Gallues not Gaulles 😃

Tahoe Quarterly

Posted at 09:16h, 09 JuneThank you, Felis. Apologies for the misspelling. The name has been corrected.

Elise Hyndman

Posted at 08:53h, 11 JuneCan we reserve the site with the chef too! And for how many people. Is there camping available on the property?