23 Apr Into the Big Blue Abyss

Since the first documented crossing in 1931, an unknown number of athletes have attempted to swim across Tahoe, intent on testing their mettle against the high altitude, cold water and enormous size of one of the world’s most famous alpine lakes

Every time Dave Kenyon took a breath, he saw the blinking lights of radio towers along Tahoe’s southeast shore. Kenyon is a “right-side breather.” This means he favors turning his head to the right in between strokes. This also means, at least on that particular September night in 1987, that breathing was synonymous with seeing the hypnotic flicker of red in the distance. It was frustrating.

“I just kept swimming and they were always there,” Kenyon recalls. “I was really getting disappointed with my lack of progress.”

Despite his frustrations Kenyon was steadily closing in on his goal—breath by breath, minute by minute—as he sought to become the third documented person to swim the length of Lake Tahoe.

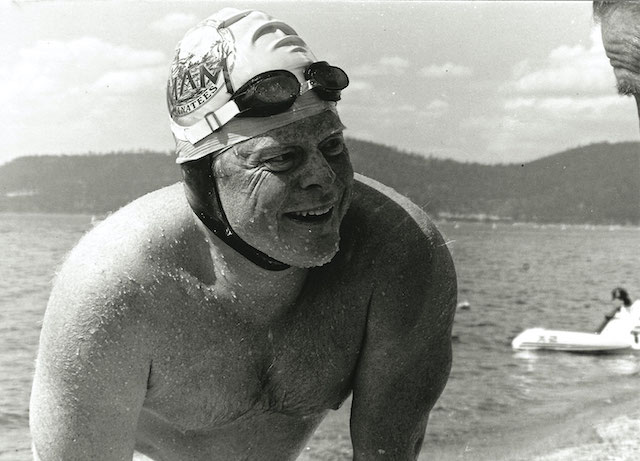

Dave Kenyon, a lawyer from Marin County, became the third person to swim Tahoe’s length when he made a 21.1-mile crossing in September 1987, photo courtesy Karen Kenyon

Some nine hours and 20 minutes after wading into the shallows of the Tahoe Keys in the blackness of night, the lawyer from Marin County emerged from Tahoe’s frigid water in Incline Village to a handful of strangers enjoying the beach. They asked where he’d swam in from.

“The other side of the lake,” he told them.

Then he got back into the water, swam out to his support boat and immediately went to sleep. He wouldn’t be able to raise his arms for the next three days, but the record for his route would stand for the next 30 years, even if the route itself would continue to evolve.

Much has changed since then. While attempts were few and far between from the first known Tahoe crossing to the turn of the twenty-first century, these impressive feats of endurance have become increasingly common in recent years. The surge can be traced to the creation of the Lake Tahoe Open Water Swimming Association, a regulatory body whose mission is to observe, ratify and promote open-water marathon swims on Lake Tahoe.

More than anything, though, the reason open-water swimmers come to Lake Tahoe is for what it offers: a challenge of immense proportions. And for those who are lucky enough—for those who have trained hard enough to make it to the other side—the experience promises rewards that are simply not available to those standing on shore.

Elizabeth Almond swims the Lake Tahoe Length in August 2020, photo courtesy SwimTahoe.com / Pacific Open Water Swim Co.

Pioneers of the Impossible

Tahoe is roughly oval in shape. It is about 12 miles wide. The north-south dimension runs just over 21 miles long, and the maximum diagonal is slightly under 22 miles from end to end.

On its surface, open-water swimming is concerned primarily with overcoming the distance between one shore and another. However, it is what lies between those shores that makes the sport so challenging.

Take Myrtle Huddleston, who swam the width of Lake Tahoe in the summer of 1931 to claim a $700 cash prize offered by the Tahoe Tavern Hotel. Huddleston entered the water somewhere near Glenbrook or Deadman Point, Nevada, bound for Tahoe City on the opposite shore.

During her crossing, a surprise wind kicked up and blew her 8 miles off course. She suffered both vomiting attacks and sinking spells. One paper reported that she was separated from her escort for two hours during the night, though her son, who accompanied her in a rowboat, disputed that claim. Finally, after swimming for nearly 23 hours, Huddleston arrived in Tahoe City to collect her hard-earned prize.

Over two decades later, in the summer of 1955, a bartender from San Francisco named Fred Rogers and a Cuban-born distance swimmer named Jose Cortinas raced across the length of the lake, starting in Kings Beach on Tahoe’s North Shore and finishing at El Dorado Beach on the South Shore.

As the crow flies, the route was supposed to cover about 20 miles. However, swimming is not flying, and the men were no crows. By the time Rogers emerged from the water—Cortinas had to be pulled from the water—a little more than 19 hours had passed. Experts debated whether Rogers may have traversed closer to 29 miles when waves and currents were accounted for.

In the early days of open-water swimming, these kinds of discrepancies weren’t uncommon. A tenth of a mile here. A mile or so there. The sport was in its infancy when Huddleston made her crossing, and it hadn’t grown much by the time Rogers completed his swim. There was still no official regulatory body or operating procedures by which to abide. Open-water swimming was less of a sport than it was a collection of ambitious individuals who, every so often, decided to test both their luck and endurance. Many failed. Some succeeded.

What the historical record can agree on is that both Huddleston and Rogers cemented themselves as famous firsts at Lake Tahoe. Huddleston was the first documented person to make it across the lake. Rogers was the first swimmer to successfully cross the length. Or, at least, a length.

Only two other people completed successful lengthwise crossings before Dave Kenyon in 1987. In 1963, 13-year-old Leonore Modell swam from Tahoe Keys to Kings Beach, adding an additional half-mile to Rogers’ route and beating his time by about five-and-a-half hours.

Kenyon knew that he wanted to swim an even longer route, even if he didn’t know exactly what that route should be. So he asked someone who did.

Buoy of Support

There is a saying in the world of open-water swimming: There’s no such thing as a solo swim.

Huddleston had her miniature fleet of rowboats. Rogers had his own crew out on the water, along with a throng of people anxiously awaiting at his destination. And Kenyon had Dean Moser.

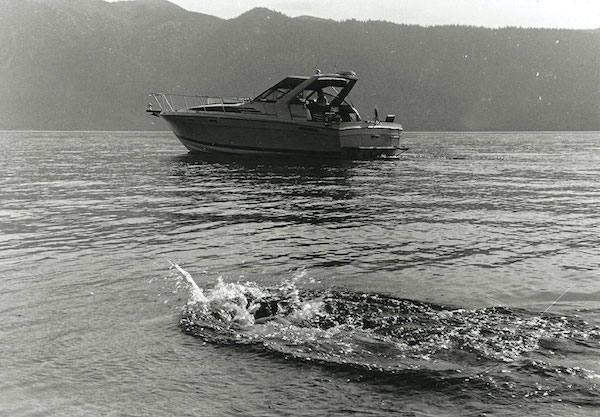

Dave Kenyon was supported on his swim by longtime Tahoe local Dean Moser and his 32-foot Bayliner, the Aqua Condo, photo courtesy Karen Kenyon

Moser was himself a swimmer. He had also spent more than 20 years boating on Lake Tahoe. He had an intimate knowledge of the area. So when Kenyon asked him what the longest possible route was for a lengthwise swim, Moser charted a course along the lake’s diagonal axis. The journey would take him between Tahoe Keys and Incline Village—a whopping 21.1 miles.

Kenyon’s wife, his coach and Moser’s wife also came along as his support crew. When Kenyon needed to replenish his energy, they tossed him a concoction of mashed fruit mixed with a hot sports drink.

Moser took the lead in his 32-foot Bayliner, the Aqua Condo, and kept Kenyon on course heading northward. Even if Kenyon had no idea how far he’d gone or how far he had left to go, Moser and the crew were keeping track.

One of the interesting things about Kenyon’s swim, at least from the standpoint of historical record-keeping, is how well documented it was. This is, in part, due to Moser, who not only kept contemporaneous notes on the crossing, but also served as the unofficial record-keeper for Lake Tahoe open-water swims. He held this position until 2011, when he passed the torch to another swimmer by the name of Dave Van Mouwerik, who would go on to continue documenting swims and compiling records through 2017.

Sylvia Lacock, a founding board member of the Lake Tahoe Open Water Swimming Association and co-owner of SwimTahoe.com, gazes across the lake. Lacock established the official 12-mile True Width when she swam it in 2017, photo courtesy SwimTahoe.com / Pacific Open Water Swim Co.

Regulatory Needs

While the phrase “open-water swimming” might suggest a kind of no-holds-barred competition between man and nature, it is worth noting that there are a strict set of regulations and procedures that govern the sport.

The Channel Swimming Association was founded in 1927 with the express purpose of drawing up a code of rules that would govern swims across the English Channel. These rules encompassed everything from what a swimmer could and couldn’t wear (goggles and a swim cap, just as long as the cap didn’t contain neoprene), to where a swim must start (England) and end (France).

Scott Kaloust, a Tahoe Triple Crown swimmer after completing all three distances, is shown with Sylvia Lacock, who supports Tahoe’s open-water swim attempts as a United States Coast Guard-licensed master captain, photo courtesy SwimTahoe.com / Pacific Open Water Swim Co.

Other regulatory associations would form throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Where swimmers swam, organizations followed. This was the case with destinations such as the Catalina Channel, the Santa Barbara Channel, the Cook Strait and, eventually, Lake Tahoe.

Founded in 2018, the Lake Tahoe Open Water Swimming Association serves much the same purpose as the Catalina Channel Swimming Federation and the Santa Barbara Channel Swimming Association. These governing bodies implement a set of general rules, standards and safety protocols, while also documenting and ratifying solo swims and maintaining historical records.

Sylvia Lacock, a U.S. Coast Guard-licensed pilot, open-water swimmer and founding board member of the Lake Tahoe Open Water Swimming Association, explains that regulatory bodies evolved out of need. As the sport of open-water swimming grew, so too did the need for some sort of professionalism and oversight. Open-water swimming is, after all, a sport. Athletes aren’t just competing with the tides, the weather and the water; they’re competing against other swimmers.

In this sense, the incorporation of the association served the other all-important purpose of adopting official routes with defined start and end points.

According to Lacock, this meant that “on any given day, whatever the conditions, you swam the same course that the person the day before swam. Or last year swam. Or five years ago.”

Thus, two swimmers, even decades apart, could still compete against one another.

The Lake Tahoe Open Water Swimming Association offers three official courses across Tahoe, map courtesy ©Mapbox, ©OpenStreetMap

These days, if you want to complete a swim with the Lake Tahoe Open Water Swimming Association, you first need to secure a date with a pilot or licensed escort vessel, which, with the growth in open-water swimming, may be booked up to one to two years in advance, says Lacock. Next, you must fill out an application. Of the two most important questions you have to answer, one is concerned with which route you’d like to swim.

While the term “across” used to be relatively amorphous, bounded only by the edges of the lake itself, the association now offers three official courses: the 10.6-mile Vikingsholm, the 12-mile True Width and the 21.3-mile Lake Tahoe Length.

The length runs from Camp Richardson on the South Shore to Incline Village, Nevada, and is about a tenth of a mile longer than Kenyon’s original route. The first person to swim the now established route was Laura Colette in the summer of 2004. The current record-holder for the length is Catherine Breed, who, almost 30 years to the day after Kenyon, made the crossing in 8 hours and 56 minutes.

Another question you have to answer is the kind that extends beyond the realm of logistics and procedure and into the nebulous territory of internal motivation.

That is to say: Why do you want to swim across Lake Tahoe?

Lake Tahoe’s Allure

It probably sounds obvious, but there are no sharks in Lake Tahoe. There are no sea lions either. The same goes for stingrays and jellyfish.

As Suzanne Heim puts it: “There are no critters to worry about.”

Heim swam the Lake Tahoe Length in August 2020. Before that, she spent most of her time out in the open ocean. During a single year in the mid-1980s, she crossed the English Channel three times. She circumnavigated Manhattan Island in 2014 and, once, during a relay swim in the San Francisco Bay, she had a surprise run-in with a curious pinniped.

Suzanne Heim before her Lake Tahoe Length swim, photo courtesy SwimTahoe.com / Pacific Open Water Swim Co.

“I thought I swam into a log and I put my head up and it was a sea lion,” says Heim. “He looked at me and I looked at him. I didn’t like that.”

Breed has also had her fair share of critter encounters. During her 2020 crossing of Monterey Bay, a route that runs 25 miles along California’s coast, she swam through sprawling blooms of jellyfish. Despite being slathered in a specially formulated repellent, Breed ended up getting stung between 50 and 60 times.

In a sport with so many things outside of human control such as tides, weather conditions and aquatic life, the absence of any one of these variables is one less thing to worry about.

In Heim’s case, the lack of critters contributed to making Tahoe one of the most relaxing swims she’s ever had.

Breed shares similar feelings.

“As far as marathon swims go, I have never had a swim as perfect as Tahoe,” she says. “It’s the pinnacle of what I’m trying to make all my other swims feel like.”

Of course, it would be dishonest to suggest that swimmers venture to Tahoe based purely on what it lacks. It would be misleading to say that the lake, even with its dearth of potentially injurious creatures, is somehow a walk in the park, because it’s not.

“Altitude, swimming in the dark and underestimating the swim as ‘just a big pool,’” are among the challenges of marathon swimming on Lake Tahoe, says Lacock, who established the official True Width course when she swam it in 2017. “We’ve had accomplished English Channel swimmers say the Lake Tahoe Length was more challenging due the altitude and fresh water.”

Seeking Sublimity

On the night of his Tahoe crossing back in 1987, Kenyon pulled over at a phone booth and called into KCBS radio to complete a brief interview. The host asked him why he was undertaking such an arduous task.

“Because I told too many people I was,” Kenyon said, “and now I’m stuck.”

Of course, he was being facetious. At least, he probably was.

Kenyon was a serious athlete, after all. Before attempting a swim through the alpine waters of the Sierra Nevada, he was training more than 50 miles a week. Social pressure may have nudged him those final few steps into the shallows that night, though it is safe to say there was a far deeper reservoir of feeling driving his decision.

Lathered in Desitin to ward off the intense sun, Melissa Filbin breaks for a feeding during her True Width swim in August 2018, photo courtesy SwimTahoe.com / Pacific Open Water Swim Co.

Motivation, much like a body of water itself, is best measured in terms of depth. There are the surface-level reasons and there are the fathomless, inarticulable motives. There are the reasons that get swimmers into the water and there are the reasons that carry them across it.

Take Georgia Wells. A tech and social media reporter for the Wall Street Journal, she likes open-water swimming because it’s the one sport in which she really can’t bring her phone with her. She completed Lake Tahoe’s 10.6-mile Vikingsholm crossing in 2018. Two years later, she traversed the True Width.

Much like Kenyon, Wells is motivated by the challenge of conquering increasing distances. In fact, she has plans to swim the Lake Tahoe Length this summer. The reason she intends to put herself through an additional 9 miles of open water has less to do with the mileage itself than it does with the act of experiencing the sublime, or at least something close to it.

In his 1937 poem Tahoe Remembrance, writer Axton Clark conceived of a world in which Tahoe is not just a body of water, but a body alive with feeling and with memory, capable of recalling everything that has happened either on its surface or in its depths. At the end of the poem, he writes:

“Deep in your drowsy level let remembrance meet / clear drops of being, cupped in the slope of time: our silver and transparent hours of peace / merged in your silver and transparent dream of age.”

Wells echoes a similar kind of poetic sensibility when describing her True Width crossing.

“When the sun started to rise a couple hours into the swim, that was the part of the swim where my mind is completely blank and I’m just staring into this blue that goes on forever,” she says. “Nothing is going through my head. That’s the ‘I’m one with Tahoe’-type feeling.”

It’s this kind of feeling that keeps Wells coming back to Tahoe, and it’s an organization like the Lake Tahoe Open Water Swimming Association that continues to draw in swimmers like her. It turns out that when you’ve got a crew of experienced people handling the logistics of your swim, you’re left with that much more time to flip over onto your back and ruminate on the divine.

The future of open-water swimming at Lake Tahoe aims to maintain its own body of carefully curated history: of stroke rates, feedings, and how much time a swimmer spends between one shore and another.

That transcendental feeling of oneness doesn’t translate as easily into the written record. It’s the kind of feeling that lives in the body of the lake itself, and in the bodies of those who have traversed its waters. To experience it, you have to get your feet wet.

And to do that, well, you just need a reason.

Matt Jones is a Reno-based writer who—especially after researching and writing this story—dreams of one day swimming across Lake Tahoe.

No Comments