23 Apr Sleuthing the Enduring Mystery of D.B. Cooper

Science forges breakthroughs in the nearly 50-year-old unsolved skyjacking

Thanksgiving eve, 1971, Reno’s high desert air was crisp and cold as dozens of local law enforcement officers and FBI agents surrounded a passenger plane that had just landed.

“We all took up positions,” Washoe County Sheriff Deputy Joe Martin later told the Reno Gazette-Journal. “I was at the north end of the runway. The plane went right over us and landed.”

When the plane came to a stop, a battalion of federal agents stormed on board, guns glinting in the lighted cabin as they proceeded row by row in hopes of apprehending the man accused of hijacking the Boeing 727 in exchange for $200,000 in ransom.

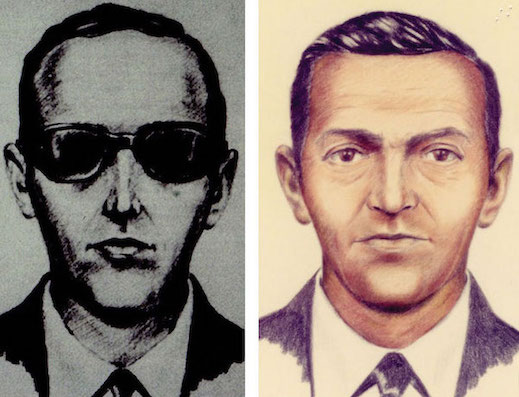

FBI artist renderings of the so-called D.B. Cooper, who hijacked Northwest Orient Flight 305 out of Portland, demanded and received ransom money upon landing in Seattle, then parachuted into the woods en route to Reno and was never found, photo courtesy FBI

By that time, approximately 10:15 p.m., the agents could hardly be blamed for their skepticism of the flight crew’s claim—that a nondescript man donning a parachute had jumped into the darkness with the stolen money somewhere between Seattle and Reno.

But after the armed search of the airplane proved fruitless, the reality of the situation began to sink in.

“That’s when we found out he was gone,” Martin told the newspaper.

Exactly who “he” is remains unknown a half-century later, as the identity of the notorious air pirate persists as one of the most intriguing and enduring true-crime mysteries in American history.

“He’s the man who beat ‘The Man,’” says Bruce A. Smith, an author who is one of the foremost experts on the unsolved case. “He’s a cultural hero of sorts. He’s just an everyday man who beat the system.”

For nearly 50 years, a slew of investigators—professional and amateur—have attempted to gain insight into the identity of the man known as D.B. Cooper. Yet, the mystery remains. Recent attempts to solve the case have gained momentum, however, as unconventional approaches to forensic science have led to tantalizing breakthroughs. While the remaining investigators may not be able to determine who D.B. Cooper is, they are increasingly able to say who he is not.

A Cold Case of Infamy

While the true identity of the man who boarded the Boeing 727 at Portland International Airport remains clouded in conjecture and uncertainty, what is known about the incident and its perpetrator have helped propel a burgeoning mystery into the stuff of legend.

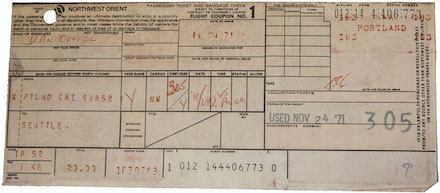

The plane ticket purchased by D.B. Cooper in 1971, photo courtesy FBI

“It’s the style in which the guy pulled it off. He was wearing a business suit while hijacking a plane and then jumped out of a plane with a bag of cash,” says Tom Kaye, a paleontologist who has dedicated considerable research to the case and leads a band of amateur sleuths in the continuing investigation. “But he was also, by all accounts, a really nice man. He even offered money to the flight attendants.”

In fact, the flight attendants and other airline employees who dealt with Cooper during the hijacking referred to him as nondescript, soft-spoken, solicitous and unfailingly polite. Such characteristics belie the audacity of the crime and the sheer danger involved in the theft.

“There are other aspects of the case that give it longevity,” says Smith. “It’s not like conspiracy theories around 9/11 or the Kennedy assassination, where the aspects are too large to kind of wrap your head around. The Cooper case, on the other hand, is plenty juicy, but small enough to grasp.”

The heist, which remains the only unsolved case of piracy in the history of American aviation, turns 50 years old this autumn, and the FBI has all but abandoned it.

“Following one of the longest and most exhaustive investigations in our history, on July 8, 2016, the FBI redirected resources allocated to the D.B. Cooper case in order to focus on other investigative priorities,” the agency stated in a release.

Paleontologist Tom Kaye, center, investigates the D.B. Cooper case along with Carol Abraczinskas and Brian Ingram, who was 8 years old in 1980 when he found $5,800 of the ransom money on a sandbar along the Columbia River, photo courtesy FBI

The FBI turned over parts of its extensive vault of evidence to a consortium of private citizens who are interested in carrying on the investigation, including Kaye and Smith.

“We’ve seen the archive,” Kaye says.

The encounter with the full spectrum of evidence and some recent scientific breakthroughs led both men to believe the identity of Cooper will be revealed, and that the revelation will likely occur soon.

“Right now is probably the best time to try and solve the case in the last 20 years,” Kaye says.

Smith agrees.

The man who committed the crime is probably pushing 90 years old if he is still alive, Kaye reasons. It’s tough to take a secret like the identity of D.B. Cooper to the grave.

“Our forensic science continues to become increasingly sophisticated and efficient,” Smith says. “Also, DNA capacities will improve over time.”

Kaye is convinced his method of investigation is superior to those of other amateur sleuths, and Smith believes Kaye’s newfangled approach is vastly superior to the FBI’s.

“I don’t investigate suspects,” Kaye says.

Richard Floyd McCoy Jr., courtesy photo

That is previously what most D.B. Cooper investigators did—find someone who fit the profile and physical descriptions provided by flight attendants and make the case that he was the guy.

Some favorites are Richard Floyd McCoy Jr., who pulled off a similar skyjacking less than five months after Cooper’s and was later caught. Kenneth Christiansen, a former Army paratrooper who also worked as a mechanic for Northwest Orient Airlines, is another suspect, as are Jack Coffelt, L.D. Cooper, William Gossett and a litany of others with relevant experience in aviation or skydiving and unexplained spending at the time directly after the skyjacking, which resulted in a series of copycat crimes across the country.

“I’m not thrilled about any of those guys,” Kaye says. “What happens is that people cherry-pick the data and find a few great reasons that their guy is the main suspect, and they dismiss everything else so they can bend it their way.”

Kaye, who is trained as a scientist, thinks it’s the wrong way to go about it.

“We look at the evidence and then develop a profile,” he says. “To date, none of the suspects match the profile.”

The Heist

The story behind history’s most notorious skyjacking began in Portland, Oregon, the afternoon of November 24, 1971, when a middle-aged man paid cash for a ticket on flight 305 bound for Seattle. He bought the ticket under the name Dan Cooper.

The Boeing 727 aircraft involved in the hijacking, courtesy photo

Upon boarding, Cooper sat in seat 18C toward the rear of the plane and in full view of the two flight attendants, Florence Schaffner and Tina Mucklow.

Once the flight was underway, at about one-third of its capacity, Cooper politely ordered a bourbon and soda. After receiving his drink, he handed Schaffner a hand-written note. Schaffner put the note in her purse, thinking little of it.

Cooper politely whispered to her, “Miss, you’d better look at that note. I have a bomb.”

Schaffner reported that the note, which Cooper later reclaimed, spelled out in capital letters that he wanted ransom money.

Cooper asked Schaffner to sit next to him and showed her an attaché case containing several red cylinders. The man told Schaffner that he wanted $200,000 in “negotiable American currency,” along with four parachutes and a refueling truck on the runway in Seattle.

Schaffner began to panic, but to her surprise, Cooper gently reassured her and requested the information be conveyed to the pilot crew. The pilot, William Scott, then relayed the information to flight control in Seattle, and local and federal authorities were notified soon after.

The flight circled Puget Sound for two hours to allow authorities time to organize the parachutes and other demands. Donald Nyrop, the president of Northwest Orient Airlines, authorized the ransom payment. During the flight, it was reported that Cooper noted several landmarks that indicated he had certain experience with flight navigation, including the exact distance to McChord Air Force Base.

When the flight landed in Seattle later that evening, the 35 passengers—the majority of whom had no idea a skyjacking was transpiring—disembarked, leaving some of the flight crew still on board.

Cooper waited on the runway for approximately two hours with the cabin shades down to ward off potential snipers. He offered all members of the flight crew the opportunity to have meals delivered while awaiting the ransom delivery and refueling, which was delayed.

“He wasn’t nervous,” Mucklow later told the FBI. “He seemed rather nice. He was never cruel or nasty. He was thoughtful and calm all the time.”

Cooper ordered a second bourbon and soda while waiting and paid for the drink, offering to give Mucklow the change.

After authorities brought four military parachutes, Cooper had them returned, demanding civilian parachutes that had manual ripcords. Four parachutes were then acquired from a local skydiving school.

The FBI also retrieved $200,000 (equivalent to about $1.3 million today) in unmarked $20 bills and photographed the serial numbers in order to track them.

The canvas bag that contained one of the parachutes given to D.B. Cooper. Cooper asked for four chutes in all and jumped with two, including one that was used for instruction and had been sewn shut. He used the cord from one of the remaining parachutes to tie the stolen money bag shut, photo courtesy FBI

The parachutes and money were conveyed onto the plane as Cooper ordered the pilots to chart a course for Mexico City. Because of his flight plan, which included maintaining the minimum airspeed possible and a maximum 10,000-foot altitude, the pilots convinced Cooper that they would need to refuel again in Reno.

The plane took off carrying only Cooper, Mucklow, Scott, co-pilot William Rataczak and flight engineer Harold Anderson, bound for Reno. Cooper initially asked the flight crew to leave the rear exit door open and the staircase extended. Air traffic control said such a takeoff wasn’t possible. Although Cooper disagreed, he did not press the argument.

Once in the air, Cooper instructed Mucklow to join the rest of the crew in the cockpit and close the door. Mucklow complied, catching one last glimpse of Cooper as he tied a bag around his waist, presumed to be the bag of money.

Around 8 p.m., the crew noticed a change in air pressure, indicating a door had opened. Rataczak engaged the plane’s intercom to offer Cooper assistance but was refused. At 8:13 p.m., the crew noticed a slight but noticeable upward movement at the tail of the aircraft. It was at this precise moment, investigators believe, that Cooper hurled himself out of the plane, with the bag of money tied around his waist, using chords from a backup parachute. He took two parachutes with him, a primary and a backup, and leapt into the dark and rainy November night.

An Elusive Manhunt

When the plane landed in Reno—with the rear airstair still deployed—there was no sign of Cooper, who was thought to have jumped somewhere near the Oregon-Washington state line.

Almost immediately, the FBI began one of the most intensive manhunts in modern history, occupying several hundred agents and spanning four-and-a-half decades.

“We interviewed hundreds of people, tracked leads across the nation and scoured the aircraft for evidence,” the agency stated in 2016, when it suspended the investigation. “By the five-year anniversary of the hijacking, we’d considered more than 800 suspects and eliminated all but two dozen from consideration.”

One of the first suspects interviewed was a Portland man by the name of D.B. Cooper. Agents hypothesized Cooper might have used his real name to buy the ticket, but after they interviewed the man, they quickly ruled him out.

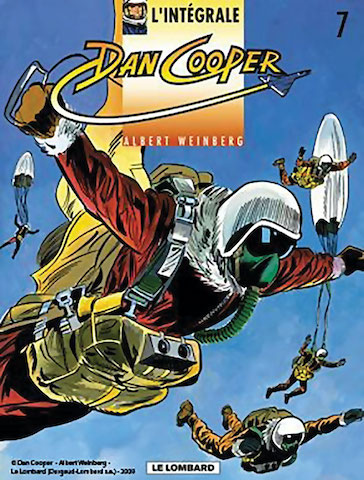

Dan Cooper was the name of a comic book series featuring a French-Canadian hero who flew and jumped from planes, photo courtesy Albert Weinberg / Le Lombard

However, a wire reporter in the 1970s misread the FBI press release and referred to the suspect’s assumed name as D.B. Cooper, cementing one of the greatest misnomers in the history of the press. The anonymous man who skyjacked Flight 305 used the name Dan Cooper, not D.B.

Dan Cooper is the name of a French-Canadian comic book hero who flew planes, piloted rocket ships and routinely jumped from planes. The comic was popular in Europe, which led investigators to believe that Cooper had perhaps spent time overseas, likely as a member of the Air Force.

One of the most prominent of the early investigators was Ralph Himmelsbach, the lead agent on the case for the FBI. The tall, lanky investigator became the face of the sprawling and persistent investigation in the years after the infamous skyjacking and often maintained his personal theory that Cooper did not survive the jump.

“My personal guess is that there is no better than a 50 percent chance that he’s still alive, and that’s being very generous,” he said in 1975. “In fact, the chances are very slim indeed.”

The difficulty of the jump combined with stormy weather and the lack of a viable landing area would have made the skydive nearly insurmountable for an extremely seasoned skydiver. Additionally, the FBI amassed evidence that indicated Cooper was not necessarily an expert. In fact, the agency later stated that he had selected an unusable parachute from the options provided to him.

Smith, the author currently investigating the case, does not buy the theory.

“He’s wrong,” Smith says of Himmelsbach.

Smith says the theory fails to account for why the body and other items were never found.

“To have everything disappear boggles the mind,” he says. “Where is the money, the parachute on his back, the other parachute, the briefcase with the bomb?”

Kaye, the paleontologist investigator, also remains skeptical that Cooper did not survive, noting that the forest in the estimated landing zone is not exactly remote.

“Typically, they find the bodies of people who go missing in that part of the forest,” Kaye says. “There’s camping there, there’s logging there.”

Larry Carr, another FBI agent who became the face of the case after a bout of renewed interest in 2007, agrees with Himmelsbach that Cooper died during the jump.

The FBI said their theory was bolstered when Brian Ingram, an 8-year-old boy vacationing with his family in the Columbia River Gorge, created the largest breakthrough in the case.

Tena Bar

It was February 1980, nearly a decade after the skyjacking, when Ingram set about building a campfire along the sandy shores of Tena Bar (often seen as Tina Bar), about 9 miles downstream from Vancouver, Washington.

Ingram uncovered three packets of the ransom cash, later confirmed by the FBI to have the same serial numbers as the bills delivered to Cooper. They were found in the same order as they were packaged.

Some of the recovered $20 bills found by 8-year-old Brian Ingram in 1980, photos courtesy FBI

It is the only piece of solid evidence to be found outside of the aircraft.

For the FBI, the discovery confirmed parts of their theory.

Cooper jumped and died somewhere in the woods near the border between Washington and Oregon, the theory goes. A portion of the money became disentangled from the rest and flowed down a tributary of the Columbia until it became buried in the sand at Tena Bar.

“We don’t like it,” Kaye says of the theory. “The money was found 20 miles away from where he jumped. We think the money belies the fact he died out there.”

The money, interestingly enough, is how Kaye became interested in the case.

“I do scientific work in paleontology, which is the study of things that have been buried for a long time,” Kaye says. “The money had been buried for a long time, so they asked me to study it.”

So Kaye, at the behest of Carr and other amateur sleuths, got involved in scientific analysis of the money. His research created one of the biggest breaks in the case, which, counterintuitively, relies on the identification of a specific algae.

Actually, technically speaking, the organisms in question are diatoms, single-cell algae that happen to be the only organism on the planet with cell walls constructed of transparent, opaline silica. Because silica arranges itself in intricate, distinctive patterns, scientists are able to identify specific diatoms that flourish in particular water bodies during seasons.

Thus, diatoms act as an algal fingerprint of sorts.

Locations where Cooper was originally thought to have landed and where some of the ransom money was later found, map courtesy FBI

“They are basically glass shells that come in tens of thousands of shapes and styles,” Kaye says. “For each different shape, there is a species.”

When Kaye analyzed the samples of the bills uncovered from Tena Bar, he found diatoms unique to the Columbia River, which was no surprise.

But what was surprising is that the particular diatoms only flourish during the spring and summer. Cooper jumped in November.

“It means the money got wet during the spring or summer,” Kaye says. “So it disconnects the burial of the money from the hijacking by about six months.”

Smith says the discovery is the most significant in decades.

“I would say that the diatoms have the potential to break the case wide open,” Smith says.

First and foremost, it presents problems for the official theory that Cooper did not survive the jump, but it also gives room for a timeline following the jump.

“The current theory is that Cooper landed somewhere near Tena Bar,” Smith says. “He buried the money and the gear not wanting to just walk out into the world with it. The money became exposed to river water, probably because he retrieved it in darkness and, in his haste, he left three or four packets behind, which the kid discovered.”

D.B. Cooper removed this black J.C. Penney tie before jumping, which later provided the FBI with a DNA sample

Kaye, a scientist by training, is less willing to wade into specific theories; instead, he focuses on the evidence and the kinds of theories and conjectures that can be excluded by evidence.

“A lot of theories go out the window, and that’s what this process is about—eliminating theories,” he says.

Another example of the theory-elimination approach is when Kaye tested the black tie that Cooper left behind in the plane after he jumped. He found trace samples of titanium, which was not a common material in the 1970s.

“That narrows the field to one of any middle-aged men who were one of the few thousand working in the titanium industry,” Kaye says.

Other scientific sampling showed rare earth metals, indicating Cooper may have worked in the aviation industry.

Both Kaye and Smith believe that, by winnowing the field of possible theories, the process of elimination will point to the one true and incontrovertible identity of one of the most famous thieves in world history—the man who either pulled off the greatest air piracy heist of all time or died trying.

Matthew Renda is a Santa Cruz-based writer and former Tahoe resident. While he hoped to land an exclusive first interview with the real D.B. Cooper, he’s happy to present the latest evidence in an unsolved criminal case that remains as intriguing today as it was when the crime was committed in 1971.

No Comments