23 Apr The Unsolved Case of Marco Siffredi

A new book by South Lake Tahoe author Jeremy Evans looks back on the life and mysterious disappearance of a young snowboarding star on Mount Everest

Author Jeremy Evans of South Lake Tahoe recently released his third book, See You Tomorrow: The Disappearance of Snowboarder Marco Siffredi on Everest, photo by Rick Gunn

Jeremy Evans was working as a sports reporter at the Nevada Appeal in 2001 when he first encountered the name Marco Siffredi while scrolling through the Associated Press wire.

“I saw he made the first snowboarding descent of Mount Everest,” says Evans, who lives in South Lake Tahoe. “I was just learning to snowboard and I thought it was a pretty cool accomplishment.”

Evans wanted to write about it then for the Carson City newspaper, but the Internet was in its infancy and he could not find enough information about Siffredi to comprise a full article. He knew Siffredi grew up in the world-famed mountain town of Chamonix, France, in the shadow of the colossal Mont Blanc, and that he was among the world’s best snowboarders, capable of climbing and riding the highest peaks on the planet.

From those faint clues about Siffredi’s prominence, Evans, nearly 20 years later, released See You Tomorrow, which plumbs the subject of the great outdoor athlete and attempts to unravel what happened to him during his second descent of Mount Everest.

‘What happened to Marco Siffredi?’

Evans was again working the AP wire in Carson City in 2002—about a year after he first learned of Siffredi—when the news came that the snowboarder had mysteriously disappeared while making his second attempt to ride Mount Everest.

This time, Siffredi had set his sights on a line through the Hornbein Couloir, a considerably more precipitous and challenging route than his first descent via the Norton Couloir. Siffredi long harbored an ambition to ride the perilous Hornbein Couloir, but he couldn’t attempt it during his first Everest expedition due to a lack of snow.

In 2001, Marco Siffredi successfully descended the Norton Couloir of Mount Everest, located in the shadows looker’s left from the summit. The following year, he disappeared while attempting the precipitous Hornbein Couloir, seen looker’s right from the summit, photo by René Robert

While the snow was sufficient for his second attempt, after an arduous hike up to the summit, Siffredi seemed uncharacteristically fatigued and distracted for a climber of his caliber—to the point that his climbing partners, Pa Nuru,

Da Tenzing and Phurba Tashi, urged Siffredi to abandon his goal.

Tashi, in particular, noticed a distinct difference between Siffredi’s demeanor on the second trip compared to the first, when he seemed more carefree, relaxed and at the top of his game.

Tashi has summited Mount Everest a record 21 times, so he was a savvy and experienced observer of the effects of extremely high altitude on climbers. Tashi said that during the first ascent, Siffredi climbed like a Sherpa, the inhabitants of the Himalayan villages of Tibet and Nepal who are renowned for their climbing prowess in the highest mountains on earth.

The second ascent, which included a 12-hour trudge through waist-high snow through the brittle thin air, sapped the Frenchman of energy.

Despite the urging of Tashi and the two other Sherpas, Siffredi, adorned in a full-body yellow snowboarding suit, tightened his bindings and rode off in the direction of the Hornbein Couloir.

As he rode away, the Sherpas lost sight of him periodically in the tatters of clouds and wind-blown snow before he descended off the crest of the summit and disappeared into the void below.

Nobody has seen Siffredi since.

“The question that I kept kicking around was, ‘What happened to Marco Siffredi?’” Evans says.

Digging into a Mystery

Evans is no longer a sports reporter. He went back to school and earned a master’s degree from Sierra Nevada College before embarking a new career as an English teacher, first at Lake Tahoe Community College and then South Tahoe High School. He also wrote a book about outdoor adventure called In Search of Powder, released in 2010, as well as a second book, The Battle for Paradise, which published in 2015.

While working on his second book project, Evans began coaching soccer as well, leading the South Tahoe High School girls to a pair of championships in 2013 and 2014. He became the head women’s soccer coach at Lake Tahoe Community College in 2015 and, four years later, took over the men’s program as well.

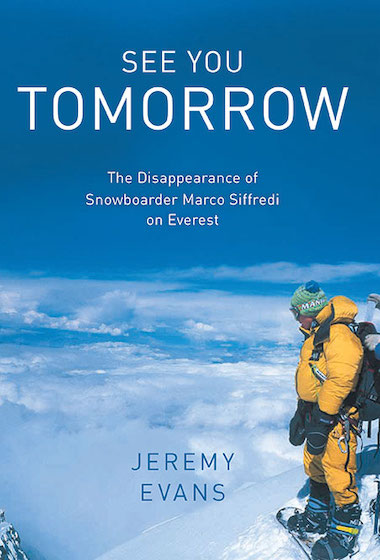

See You Tomorrow: The Disappearance of Snowboarder Marco Siffredi on Everest

Yet all the while, the question of Siffredi and what happened to him on that fateful day nagged at Evans.

“I knew his family ran a campground, where Marco worked and made wages to fund his various snowboarding trips. So the summer of 2017, I figured I’d travel to Chamonix and maybe try to do some research,” says Evans. “My wife and I went with another couple and I figured if we got shut out of research, we’d do the Haute Route from Chamonix to Zermatt.”

Before departure, Evans reached out to two of Siffredi’s best friends—René Robert and Bertrand Delapierre. From them, he gleaned that, while a pair of books about Siffredi had been published in French, the literature on the young adventurer was surprisingly and unjustifiably scant in English.

So Evans traveled to Chamonix without being totally sure if he had a book-length subject, deciding to stay at the campground run by Siffredi’s parents.

Once there, Evans noticed Siffredi’s sister, Valerie, going about her business. And while initially coy about approaching her about such a sensitive and traumatic event, he eventually introduced himself, initially emphasizing his personal interest in her brother while downplaying his desire to write about him.

“She said I could come back to the general store she ran and talk, but she did not want me talking to her parents at first,” says Evans.

Evans eventually contacted the family and garnered more information, but he still was not sure he had a book. However, he had another contact in Kathmandu, the capital of Nepal and gateway to the Himalayas. Russell Brice, a famed mountaineer from New Zealand who has climbed Mount Everest a handful of times, owns a Kathmandu-based expedition company that helped Siffredi successfully descend Everest on his first expedition.

Additionally, Brice was influential in Siffredi’s career arc, convincing him to take on some of the more manageable high mountains in the Himalayas before tackling Everest. Brice helped Siffredi plan and successfully ride Cho Oyu, the world’s sixth-highest peak at 26,864 feet.

Siffredi’s friends say it was during a trip to ride Dorje Lhakpa, a 22,854-foot mountain in the Himalayas, that Siffredi first laid eyes on Mount Everest and became obsessed with becoming the first person to descend it on a snowboard. While the sight of Everest in the distance captured his imagination, the fact that he became the first person to descend Dorje Lhakpa on a snowboard gave him confidence to up the ante.

A master of the steeps, then-20-year-old Marco Siffredi became the second person, and first snowboarder, to descend Nant Blanc, the famous face of Aiguille Verte in the Mont Blanc massif, photo by René Robert

Tracing a Rising Star

All of this percolated either despite, or because of, his youth.

Siffredi was only 23 years old when he disappeared, yet he accomplished a lot in terms of alpine freeriding. It helped growing up in Chamonix, which for many is the cradle of alpine mountaineering.

Siffredi’s dad, Phillipe, sometimes guided in the mountains around Mont Blanc when his son was a child, but Marco Siffredi looked more to the accomplishments of his peers, some of whom were taking on the most dangerous lines ever attempted on a snowboard. Siffredi wanted some too.

At 17, just one year after learning to ride a snowboard, Siffredi successfully rode one of the most courageous lines in the Mont Blanc region—the Mallory on the North Face of the Aiguille du Midi, which features about 3,000 vertical feet with 55-degree slopes and plenty of rocks to navigate.

“I think the most impressive line is when he skied the Nant Blanc,” Evans says. “The Aiguille Verte is the hardest descent off of Mont Blanc. Marco was the second person to ever do it and the first to do it on a snowboard.”

He was 20 at the time. After the Aiguille Verte, Siffredi successfully climbed and snowboarded a few ludicrous lines high in the Andes, including 19,974-foot Huayna Potosi in Bolivia.

It was around this time that he met Brice, who convinced him that Everest could be done, but only after he bagged a couple of other 8,000-meter peaks. There are only 14 mountains on earth higher than 8,000 meters, approximately 26,250 feet, eight of which are in Nepal.

Brice played a large role in feeding the ambition of Siffredi, and coincidentally, he played the same role for Evans. When the two met in Kathmandu, it was Brice who convinced Evans there was enough material for a book.

“So I started working on it,” says Evans.

A Poignant Project

The work was difficult, particularly given language barriers and the emotional weight of the subject.

“I’m cold-calling people who have buried this tragedy in the recesses of their minds and hearts, and I’m just excavating all these memories,” Evans says.

At one point, Evans reached out to Siffredi’s girlfriend Stephanie, who runs a boutique clothing store in Chamonix. Initially, she agreed to talk to him, but hours before the interview she emailed to say she wasn’t up to it.

Marco Siffredi is all smiles after his descent of Nant Blanc, photo by René Robert

Siffredi’s mother, Michelle, also declined to speak to Evans for the book, saying the memory of losing her son was too painful. Tragically, Michelle Siffredi lost both of her sons to the mountains, as her eldest, Pierre Siffredi, died in an avalanche when Marco was just 18 months old.

For Evans, experiencing the grief of Siffredi’s family in such an intimate, personal way compelled him to try to tell the story in a manner that pays tribute to his legacy not only as an athlete, but as a person.

“I hope his family respects what I wrote,” Evans says. “I wanted to get it out to an American audience. For me, I obviously care about the climbing and the snowboarding part, but this is a story that has a lot for a general audience.”

Specifically, Evans slowly unravels Siffredi’s character throughout the book, and it reveals a complicated young man, driven by ambition, fueled by a bounty of natural talent, but also wary of the trappings of fame, endorsements and the other accouterments that accompanied superstar snowboarders of the time.

“He never felt the need to take advantage of his talents to take it easy,” Evans says. “He could have done freeride championships, but he didn’t like it. He wanted to focus on the mountains and not compromise his values.”

Siffredi didn’t seek sponsorships. Instead, he worked for his family’s business just long enough to fund his various expeditions.

Evans is also convinced that Siffredi’s punk rocker exterior—replete with hair dyed manifold colors, studs in his ears and a sort of wild, gap-toothed look—belied his down-to-earth sensibilities and capacity for authenticity and connection to his small coterie of fellow adventurers.

“When you pulled that veil down, what you saw was a genuinely caring person,” Evans says. “He seemed eccentric and crazy, and in some ways he was, but he was shy and reserved around most people.”

Siffredi on his first descent of 22,854-foot Dorje Lhakpa in Nepal, photo by René Robert

Due Respect

What Evans saw most in Siffredi was an unrivaled ambition matched only by talent. It is rare for alpine climbers of Siffredi’s ilk to combine those elite skills with world-class snowboarding. It was that rare combination that afforded Siffredi the opportunity to run the globe’s most daunting lines.

“His progression was very quick, but he didn’t skip any rungs,” Evans says.

While many criticized Siffredi as young and reckless, Evans says he was calculated in the risks he took. He studiously progressed from large mountains in the Alps to the Andes to the Himalayas, all the while taking stock of his own abilities and how they matched up against what was possible in the mountains.

“He wasn’t fatalistic; he wasn’t cavalier,” Evans says. “All of that was overshadowed by his passion to live and his passion to snowboard. That was his true purpose—to snowboard.”

Siffredi’s story had pull for Evans also because it was a tragedy with a mystery at its heart.

Many people have tried to figure out what happened to Siffredi that day. When Brice heard that Siffredi had disappeared, he combed the area beneath the Hornbein Couloir but found nothing. Some groups have attempted to climb the Hornbein Couloir in the years since, but none have succeeded.

No one knows what happened on that fateful day in September 2002.

Phillipe Siffredi believes his son may have gotten tired at the top of the couloir and paused to rest, only to succumb to the effects of altitude and fatigue. Others think he may have gotten caught up in the crux of the couloir and his body could possibly still be there. Some even think Siffredi survived and disappeared into anonymity, perhaps living simply in a Himalayan village somewhere.

Evans has his own theory. But to encounter that, you’ll have to read the book.

See You Tomorrow is available at Amazon and falcon.com, as well as select bookstores around the lake.

Matthew Renda is a Santa Cruz-based writer and former Tahoe resident. He enjoyed reading See You Tomorrow and would recommend the book to anyone.

No Comments