25 Apr California’s New Wolves Stir Old Divisions

As the gray wolf continues its remarkable recovery across the Mountain West, this once-dominant predator’s return to the Golden State after a nearly century-long absence presents inevitable challenges and controversies

Gray wolves, which were eradicated from California by 1924, are making a return to the Golden State, photo by Gary Kramer, courtesy US Fish and Wildlife Service

Throughout history, the fate of wolves has been tied to the attitudes and actions of humans. This long history is filled with thousands of years of deification and reverence for the animal, and vicious killing campaigns and demonization that nearly wiped the species off the American landscape. Even more recently it has included reintroduction that led, through an ecological chain reaction, to wolves returning to California.

Today, a unique opportunity to reassess the wolf is in progress. It has grown from an experiment in the Northern Rockies to a phenomenon that has spread across the Mountain West. The wolf is back, and so is the controversy that comes with this powerful predator. The divide between urban and rural, between private industry and government intervention, between wildlife and livestock, continues to be a flashpoint of controversy that the wolf incites like no other animal.

During the wolf’s century-long absence from California, the furor around these animals dwindled. But now, as four wolf packs reestablish within the state, including one pack within an hour’s drive of Lake Tahoe, the wolf has once again captivated California.

Fear, love, admiration, hate—these widely divergent emotions are all once again trained on perhaps the most mythologized, misunderstood and divisive animal in the country, stirring up fierce reactions on barstools, across ranchlands and at public forums throughout the state.

“It’s fundamentally true that people are emotional about wolves and become extreme quite easily,” says Arthur Middleton, a UC Berkeley professor who has worked on wolf issues in the Northern Rockies. “But at the same time, I have known individuals who have gradually changed, including ranchers.”

Meanwhile, the wolf is just doing what it has always done—trying to survive in a landscape that has changed dramatically since wolves last lived in the Golden State.

With protection by both the federal and state Endangered Species Act, the future of a permanent California wolf population seems inevitable. After 100 years of absence from the California landscape, the state is going to have to learn to live with wolves again.

Ancient and Brand New

While the reactions to wolves are, in some way, as old as time itself, in other ways, everything is brand new for this generation of ranchers, land managers, wildlife biologists and decision-makers. Trying to secure a new future for the species without repeating the mistakes of the past is testing human nature’s ability to forge agreement and understanding rather than splinter into conflict and division.

“It’s new wolves in new places with new people,” says Kent Laudon, a senior environmental scientist with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. “The new part is the scariest, freakiest, hardest part of the whole thing.”

A member of the Shasta Pack in 2015, photo courtesy California Department of Fish and Wildlife

In California, ranchers are faced with very real conflicts. The animals, far removed from the abundant elk of the Northern Rockies, must rely on smaller prey and are adapting with larger home ranges and smaller pack sizes. Sometimes wolves end up preying on livestock, reopening old fears and frustrations that have led, in part, to the wolf’s demise in California nearly a century ago.

“It is like having a robber out there around your place at night, knowing that something is going to get killed that night. And there is nothing you can do about it,” says Rick Roberti of Roberti Ranch near Loyalton, who is president of the Plumas-Sierra Cattlemen’s Association.

For Roberti and other ranchers, the issue is not only that wolves will prey on livestock, including opportunistically picking off calves during and after calving season. The wolves also stress the entire herd, which can lead to cows aborting calves and other problems. Roberti says six of his calves on a range near Vinton have been killed by what he believes were wolves. The cause of the deaths could not be confirmed because coyote DNA was found on the calves, a result, he says, of coyotes scavenging the carcasses after the wolf attacks.

For ranchers already contending with bears, coyotes and mountain lions, the addition of wolves to the landscape is not a welcome development.

“There is not much of a place for more predators,” says Roberti.

The rancher also has an interesting perspective on the historic prevalence of wolves in Sierra Valley. His family dates back to the 1920s in the area, and he believes that there were few wolves in the area historically.

A gray wolf drinks from a water guzzler in Lassen National Forest in August 2018, photo by T. Rickman, courtesy U.S. Forest Service

“I have talked to Native Americans around here and they say we didn’t have wolves here,” says Roberti. “There could have been wolves that came through, but we didn’t have packs here.”

With limited recorded history of past wolf distribution in California—anecdotal historical accounts about wolves are considered unreliable because of frequent confusion with coyotes—it’s hard to definitively say to what extent wolves populated Sierra Valley.

Despite the frustrations with the new wolves, Roberti says ranchers in Sierra Valley are playing by the rules and understand that the wolf is protected by state and federal law.

“Ultimately, our hands are pretty tied,” says Roberti.

And as the wolf issue has ballooned into an urban-versus-rural controversy, he wants people to know that ranchers like his family that have tended to the land for generations care about the landscapes they live on and dedicate themselves to protecting it.

“We’re doing a good job taking care of the land. When you drive into Sierra Valley you see the open space. It’s not like other places where ranchettes have sprung up. We’re taking care of the land in a good way and making it better for future generations. We’re not just doing it for the money,” says Roberti. “We just want our stories to be heard a little bit.”

As for the wolves?

“I think we just hope they’ll find out this isn’t home and move on,” he says.

While it is perhaps predictable that conflicts between livestock and wolves will arise, the frequency of predation seems to be random, Roberti and Laudon agree.

“The interesting thing is that wolves in these livestock areas, they live with cattle. Our packs, like other packs, are traveling through cattle every night. And oftentimes nothing happens. But then sometimes it does,” says Laudon.

Wolves, if left to their own, would adapt and colonize and find equilibrium with the deer and elk herds within their surroundings. However, a landscape populated by ranches and farms and homes presents a whole new set of challenges for both humans and wolves.

“One of the big influencing factors for wolves is just people—and we’ve seen that with the Northern Rockies,” says Laudon. “The more you separate people and wolves the better the wolves are going to do. It is everything from highways to poaching and livestock conflicts. Those conflicts can be a precursor of things.”

From Deity to Devil

Our modern experiences with wolves is a mere blink of an eye in the long sweep of history between humans and Canis lupus. Rewind time several hundred years and an entirely different relationship between the two species emerges.

The Paiute Tribe, which populated the Great Basin, revered the wolf as the creator of man. In their origin story, Tabuts, a wise wolf, carved many different humans out of sticks with plans to scatter them evenly across the planet, so that every people had a suitable place to inhabit. But Tabuts’ younger brother Shinangway, a coyote, cut open the bag where he carried the sticks and the people tumbled out in bunches. This, the Paiutes believe, is why people fight. The southern Paiutes were the final sticks that remained in the bag, and were placed by Tabuts in the very best place.

A captured gray wolf in Wyoming in 1887. Starting in the nineteenth century, wolves were hunted to near extinction due to the threat they posed to ranch owners, photo courtesy Library of Congress

For thousands of years, humans and wolves coexisted and survived by following similar patterns. They both migrated with the seasons and pursued prey for food. An admiration and understanding grew, as the wolves’ unflagging stamina, keen senses and societal structure of pack formation were held in high regard.

As ranchers, miners and farmers began pushing westward, the perception of the wolf changed dramatically. Wolves were a perceived, and real, threat to livestock. For a small-scale farmer or rancher eking out a living with a couple of cows and chickens, a wolf raid could mean the difference between survival and starvation.

This was an era of utter devastation for wildlife across the continent. In a matter of decades, the entire ecosystem of the country was transformed. Passenger pigeons, which were estimated to number up to 5 billion before European colonization, were extinct by around 1900.

The teeming herds of bison, an estimated 60 million in the late 1700s, numbered only 541 by 1889. Wolves did not escape this fate. They were perhaps hunted, trapped and poisoned with a fervor and ferocity unmatched in history.

“No other wolf killing ever achieved either in geographic scope or economic or emotional scale the predator-control war waged against wolves in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in the United States and Canada,” writes Barry Lopez in his classic text Of Wolves and Men.

Wolves were killed for pelts by trappers, then they were killed by the tens of thousands as government bounty programs offered rewards. Wolves were injected with mange and released into the wild to spread the disease among packs. Poison-laced meat was strewn across the landscape by bounty-seeking wolfers, killing not only wolves but badgers, foxes, coyotes, wolverines and anything else that fed on the carcasses.

These widespread killings were propelled by propaganda, fantastic inventions about the evil nature of wolves.

“It is hard to look back on this period in American history and understand what motivated men to do what they did, to kill so thoroughly, so far in excess of what was necessary. In Montana in the period from 1883 to 1918, 80,730 wolves were bountied for $342,764,” writes Lopez.

By the 1920s wolves were effectively eradicated from most of the West. The last known wolf in California died in 1924 in Lassen County. The animal that had once been a deity to man had become a devil hunted to the ends of the earth.

The Beckwourth Pack

Laudon was studying the Whaleback Pack in Siskiyou County last year when he heard about wolves much farther south.

“I dropped everything and went down to Sierra and Plumas counties,” says Laudon, whose team found evidence of at least three wolves and ended up finding enough tracks and scat to identify one wolf as a female.

Wolves of the Beckwourth Pack north of Lake Tahoe are pictured from a trail camera along with a black bear, photo courtesy California Department of Fish and Wildlife

Then the wolves began showing up in trail camera footage.

“They would come by once every two to three weeks and then they’d be gone again,” says Laudon.

The pack is still somewhat mysterious. With no radio collars on any of the wolves, it is hard to track their movements or determine if the pack is reproducing.

“There may not be any pups,” says Laudon. “After detection of three wolves, all we ever got were two wolves.”

Laudon is currently waiting for access to land to continue investigating the pack.

While the Beckwourth Pack is the closest to Tahoe, three other California packs persist in the state—the well-established Lassen Pack, the Shasta Pack and the Whaleback Pack in Siskiyou County.

Persistent Mystery

With all the studying of wolves, abundant mystery remains. The animals have consistently surprised experts and surpassed expectations.

“The thing about wolves is to not underestimate that they are really big travelers,” says Laudon. “Wolves are kind of like the long-distance runners of the animal world—compared to lions, which are the gymnasts of the animal world.”

A wolf pup howls in the wild, photo courtesy California Department of Fish and Wildlife

Nobody really knows how many wolves are in California or even where they are located. One wolf, which scientists named

OR-54, traveled an astounding 8,700 miles, crisscrossing the state and venturing into Nevada and back to Oregon. Another wolf, OR-93, loped to Monterey County and San Luis Obispo County before he was struck and killed by a vehicle along the Grapevine in Southern California in November 2021.

And scientists only know this because these wolves were radio-collared and could be tracked. Where un-collared wolves are wandering is still an open question.

“Obviously we don’t detect everything,” says Laudon. “The chance of just detecting a wolf just passing through has got to be really low. … Wolves are habitat generalists. All they pretty much need is big game. Anywhere there is big game, they can live, except where people won’t allow that to happen.”

Despite their remarkable resilience, wolves in modern California do prefer cover and quiet. Because of this preference for solitude, it is unlikely that wolves would choose populated areas around Truckee or Tahoe as a home base.

“Forested, mountainous areas with lower road densities,” Laudon says of the animal’s ideal habitat. “More big game is better. Basically, it is a security model.”

The Future of Wolves in the Golden State

The wolf recovery throughout the West has been nothing short of stunning. Starting with several dozen wolves re-introduced from Canada into Yellowstone and Idaho in the mid-1990s, the animals have spread across the Mountain West persistently.

The recovery has been punctuated by its share of controversy and challenges. Most recently, a delisting of the species from the Federal Endangered Species Act resulted in a period where wolves were once again hunted and trapped in widespread fashion. Lawsuits were filed, and wolves returned to their endangered and threatened status (although wolves in the Northern Rockies are managed by the states).

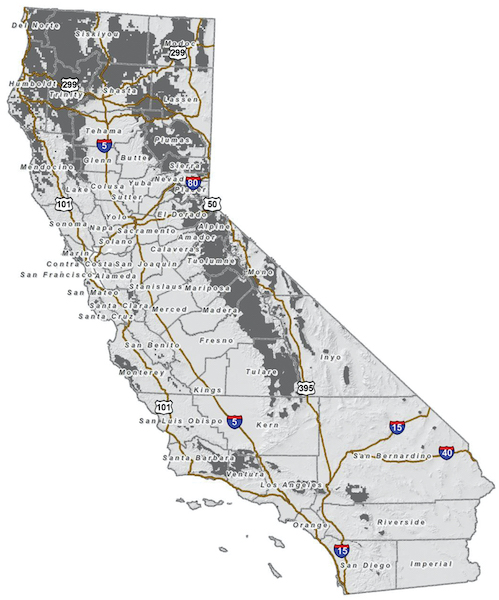

Potentially suitable habitat for wolves in California delineated in dark gray. Prey abundance, public land ownership and forest cover increased the probability of wolf occurrences, whereas human influences and domestic sheep presence decreased the probability, map courtesy California Department of Fish and Wildlife

In California, a strong state Endangered Species Act makes killing wolves illegal and should help protect the species as it recovers. Yet that has not stopped wolves from dying under circumstances that are under investigation.

In 1978, Lopez published his seminal work on wolves with Of Wolves and Men. At that time, wolves had not been reintroduced to the Northern Rockies, but Lopez urged a deeper understanding and a clear-eyed coming-to-terms with our shameful history with the animal:

“I think, as the twentieth century comes to a close, that we are coming to an understanding of animals different from the one that has guided us for the past 300 years. … The appreciation of the separate realities enjoyed by other organisms is not only no threat to our own reality, but the root of a fundamental joy.”

The book was reprinted in 2004 with a new afterword by the author. By this time, wolves had been reintroduced to the Northern Rockies and were starting their expansion across the Mountain West.

“It is easy, I think, to underestimate the emotional impact wolf reintroduction has on many Americans,” writes Lopez. “For some, considering the near maniacal way in which the animal was once hunted down, it’s been like reconciliation with a bad dream. Scientists contend we will never be able to completely restore the ecosystems in which wolves once lived, but many now feel we’ve been able to at least restore some sense of our own dignity by successfully implementing and managing wolf reintroduction programs.”

Lopez wrote the afterword during a time when he was attending public meetings in Oregon surrounding the wolf issue. Wolves were moving from Idaho into Oregon, much in the same ways they are now moving from Oregon into California.

From these meetings, Lopez notes two things: “The wolf is a much less demonized animal than it was,” he writes, while conceding that the animal “continues to generate more adamant positions and to trigger more powerful emotions than any other large predator in the northern hemisphere.”

Laudon has seen these same strong opinions and emotions in his work across the state. But there’s no pessimism in his approach to working with wolves and, perhaps more importantly, people throughout the northeastern parts of the state.

“I think, sometimes counterintuitively, could the wolf be the thing to bring people back together again?” he asks.

Given the centuries of division the animal has brought, that might seem like fanciful thinking. But considering how far wolves have rebounded across the landscape, and how much of a role humans have played in that remarkable ecological recovery, it may actually be a dose of clarity and perspective in the raging debate.

“We know we have changes as a nation from thinking every wolf should be killed to thinking that we should have them around,” says Middleton.

That is good news. And with wolves, there is actually a lot of good news.

“We still manage to tell the story of wolves in terms of it all being bad news,” says Middleton. “We like to tell the story of the two steps back and not the story of the step forward.”

Middleton says that if you flip that thinking around and look at what has happened over the past three decades, the wolf’s recovery is a truly remarkable comeback tale.

“While there are few wolves in California, they are part of a pretty large and pretty recovered wolf population,” says Middleton.

And perhaps this is where biology and sociology diverge. Biologically, the wolves have made an impressive comeback. But finding an equilibrium with the humans who introduced them back into the wild is still a work in progress.

Doug Smith, the wildlife biologist for wolf reintroduction in Yellowstone National Park in 1995 and 1996, noted this from the earliest days of the wolves’ return to the Mountain West.

“The biggest problem wolves have is everyone has an opinion about them, and much of it is based on misinformation,” said Smith in a 2012 interview. “Separating the folklore, the misinformation of what wolves are really like is an important step in managing them in reality, because we’ve been managing them in mythology for a long time.”

David Bunker is a Truckee-based writer and editor.

No Comments