26 Apr Crystal Bay Club: From the Brink of Oblivion

Left for dead 20 years ago, the last non-corporate casino in the Tahoe Basin continues to thrive thanks to the vision of its owners, who opted against grandiose development to create a spot for locals and visitors to enjoy good music

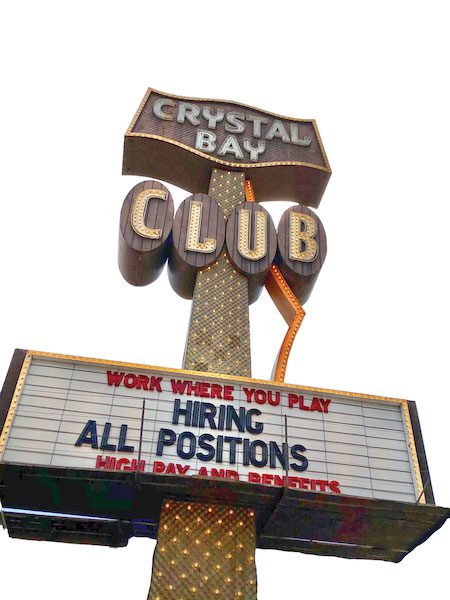

The Crystal Bay Club sign stands out as a beacon when crossing the state line on Tahoe’s North Shore, courtesy photo

Things weren’t looking great for the Crystal Bay Club in the spring of 2002. In early April the casino—just steps away from the California-Nevada border on Lake Tahoe’s North Shore—was forced to file Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

Not soon after, it went dark—seemingly for good.

Like many of its counterparts, the casino was beset with issues getting the books to pencil out in the wake of 9/11. Local foot traffic was way down, travel from other regions was nearly non-existent, and at the same time, tribal casinos in the region were on the rise, making a sizable dent in Northern Nevada’s monthly gaming take.

On top of everything else, the Crystal Bay Club—or CBC, as it is known—was the smallest fish in the area, with no hook to boot. Bereft of accommodations, there was no “stay and play” option. Additionally, there wasn’t much of an identity—no “wow” factor.

The CBC didn’t have the history or nostalgia of the neighboring Cal Neva Resort once owned by Frank Sinatra. It didn’t have the nightlife (or 24-hour $1.99 breakfast) of the Tahoe Biltmore across the street. It didn’t have the gaming footprint or corporate clientele of the Hyatt Regency Lake Tahoe Resort & Casino in nearby Incline Village. There wasn’t even the folksy Nevada name-brand, small-footprint, slots-only appeal of its next-door neighbor, Jim Kelley’s Nugget.

But the CBC did have one thing: “They have financial problems,” Ed Yenick, a deputy chief of the Nevada Gaming Control Board, said at the time.

“I have to admit: I didn’t see a way through for them,” says longtime Crystal Bay real estate agent Ann Nichols. “I don’t think any of us did.”

Well, one person did.

His name is Roger Norman.

The Man Who Saved the CBC

Norman is a Northern Nevada entrepreneur and developer. His projects are varied, from owning an industrial park just east of Reno that houses Tesla, Google and Walmart, among others, to financing a ring road around nearby Fernley to encourage commerce and increase infrastructure. His hobbies, which include professional offroad racing—highlighted by a coveted win in the Trophy Truck division of the famed Baja 1000—are illuminating.

Roger Norman and wife Elise receive a tile on Ensenada’s Walk Of Fame commemorating Norman’s win with Larry Roeseler in the 2008 SCORE Baja 1000, courtesy photo

While Norman’s fingerprints are all over Northern Nevada, he is also reclusive. Now 85, the last interview he gave was in 2018 to Arianna Bennett of Channel 2 KTVN in Reno. There, he broke down in tears multiple times, admitting he was forced to work at his father’s gas station as a teenager and never learned to read or write. He also said he’d lost everything—more than once: “I’ve been the American dream three times,” he said. “I’ve been broke twice. Flat broke. It’s terrible. I don’t recommend it.”

Norman said what kept him going was his capable team who manage the day-to-day while he keeps a low profile: “I’ve just been lucky in making the right decisions,” he said. “I’m sure that has to do a lot with the team. I negotiate from the shadows. You gotta have the guys that can pull it off—that’s the guys up front.”

One of Norman’s right hands is Lance Gilman, who made headlines in 2003 when he bought the Mustang Ranch brothel near Reno for $145,100. “If anybody tried to smoke him—he knew what was going on,” Gilman told Bennett. “Roger is watching every single thing that happens and he either blesses it, or it’s a no.

“He’s a leader. He’s a champion.”

Norman has said he never intended to own a casino until one fateful evening in the fall of 2002. He and his wife Elise were driving home to Reno after seeing a show at the Cal Neva during an early-season storm. Norman glimpsed the darkened casino’s marquee, barely visible through the sleet—and it was there he saw a sign.

And the sign said, “For sale.”

By the end of the month the couple would have the keys to the property for less than half the cost of a lakeside home in Crystal Bay.

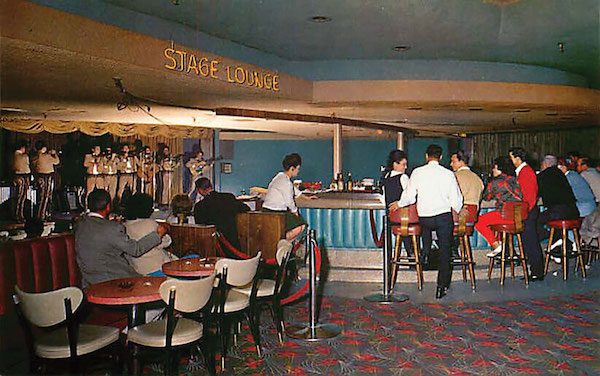

A postcard of the Crystal Bay Club stage lounge in the early days of the casino, courtesy photo

“I think they bought it for like $4 million,” Nichols says. “Unheard of, cheap! Even at the time.”

Beyond the price tag, the Normans recognized the one positive the casino did have going for it: location.

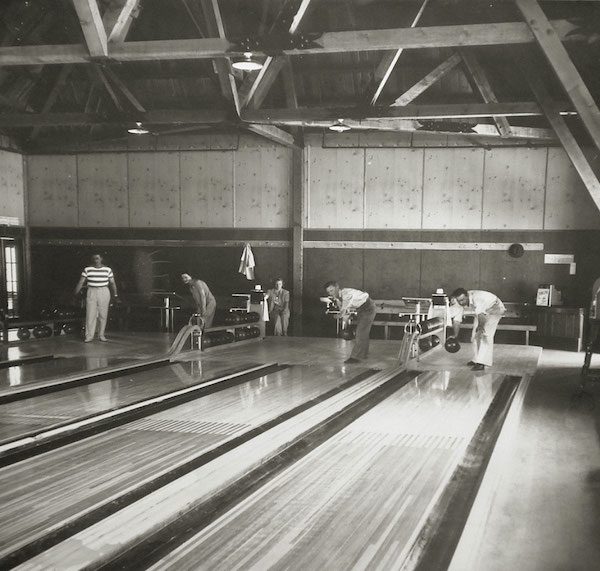

Just a couple of rock skips from the lake’s shores, the property was sought-after. But after a few potential sales, including one failed attempt by a member of the casino’s previous ownership group, common wisdom was that the Normans would raze the building—which opened in 1937 as the Ta-Neva-Ho bowling alley and The Bucket of Blood Bar—and help facilitate plans to put a bottled water plant there instead.

But the Normans never did what was expected of them, so the casino stayed.

New Life for a Tired Casino

Though purchasing the parcel may have been a lesson in picking up distressed property for a song—the actual purchase price of the casino was $2.9 million, plus an estimated $3 million the Normans sunk in right away to bring the property up to code, including asbestos removal—the CBC’s identity problems persisted for the Normans just as it had for a conga line of ownership groups, about one every decade, since the 1960s.

And the riddle remained: What was going to get people to the CBC—and keep them coming back?

The Crystal Bay Club originally opened in 1937 as the Ta-Neva-Ho bowling alley and The Bucket of Blood Bar, courtesy photo

Turns out, the answer was hiding in plain sight.

The Normans continued to invest in the property in an effort to restore some glory. They hired new staff from the top down. They refurbished the gaming space. They put in a small bar-lounge for weekend revelers and local cover bands on the east side of the main building. They opened the doors at the height of summer season, August 1, 2003.

And the people came—at a trickle.

About six months into the new venture, the Normans realized what many Crystal Bay Club owners had before them: Things were slow on Tahoe’s North Shore. They tried gaming promotions, slot tourneys, lounge acts—and experimented with a new chef and tough-to-beat surf-and-turf deal. Norman even attended University of Nevada, Reno’s executive casino management program in the summer of 2004.

In December of that year, Norman told the Reno Gazette Journal he spent weeks at a time at the casino without leaving. “I didn’t care,” he said. “It didn’t feel like work.”

Still, something was missing.

One day within the first year of reopening, Norman was showing off the joint to Beach Boys front man Mike Love, who lives in Incline Village.

Norman and Love paused in the space just off the main gaming floor, which housed the casino’s cafe. The ceilings were low-slung, and the booths were threadbare and cramped. The restaurant was dark and windowless—and practically empty.

Formerly a cafe, a space off the main gaming floor was converted into a top-notch music venue known as the Crown Room, courtesy photo

And that was a good thing.

Norman pointed out to Love that the space was originally used as a bowling alley, and joked that maybe he should just tear it out and start over with that. Both commented they could almost hear the pin action ricochet off the walls as their voices echoed.

Then it hit Love. He turned to Norman and told him to forget the lounge and small stage on the other side of the gaming area—this was the music venue.

True to form, the Normans went all in.

The cafe shut down and the ceiling was removed to reveal the building’s original rafters. The Normans outfitted the space with industry-best sound and lighting and hired the best in the area to spearhead the new endeavor.

They poached a new general manager, Bill Wood, from the Hyatt in Incline. And along with Wood came Brent Harding, a talent booker, and Blake Beeman, the region’s best sound and lighting guy.

They built it—and the acts followed.

A Simple Recipe for Success

New Year’s Eve 2003 was the debut of the newly minted Crown Room and featured multi-instrumentalist Edgar Winter and guitarist Coco Montoya played to the first of thousands of sellout crowds there.

Andy Frasco & the U.N. performs in the Crystal Bay Casino Crown Room on March 16, 2023, photo by Ryan Salm

The Crown Room, with a current capacity of 750, has hosted legacy acts: Dick Dale, Blues Traveler, Blue Oyster Cult, the Chris Robinson Brotherhood, the Neville Brothers and Dr. John. It has broken today’s stars like Billy Strings, Gary Clark Jr., Trombone Shorty, Derek Trucks and Joe Bonamassa. The Crown Room has also given rise to local acts getting to the next level: Jackie Greene, Dead Winter Carpenters and Devil Makes Three.

And, yes, for Tahoe locals of a certain age, if you haven’t been to a Tainted Love show on Halloween and made out with that certain special someone in a sexy bee costume, you haven’t lived Tahoe.

In 2008, Wood hired Eric Roe, who succeeded him as GM upon his retirement earlier this year. Roe, a Michigan native and Incline Village resident, says he’s spent the last decade and a half “learning from a literal giant” (Wood is 6 foot 3). He says it’s Wood’s and the Normans’ ethos that keeps the casino going as an independent entity in a time when the fates of their neighbors are uncertain.

After several ownership groups made big promises and eventually ran the Cal Neva into the ground in the early 2000s, billionaire Larry Ellison bought the dormant property out of bankruptcy in 2018 for $35.8 million, but still it remains dark. Ellison doubled down, buying the Hyatt in Incline in 2021 for $345 million.

In April, shortly before this story went to press, a Denver-based real estate firm acquired the historic Cal Neva property from Ellison and announced plans to turn the casino into a luxury Proper Hotel set to open in 2026.

Crystal Bay Casino’s new general manager, Eric Roe, left, with former GM Bill Wood after Wood’s recent retirement, photo by Tim Parsons, courtesy Tahoe Onstage

Even with news of the Cal Neva purchase, the Nevada corridor of North Lake Tahoe remains in a kind of limbo.

The Hyatt is still running with rumors of future development on the property’s lakefront side. The Biltmore, which for 15 years was planned to be redeveloped into a hotel-timeshare-convention-public space known as Boulder Bay, was purchased by an Orange County-based group in October 2021 for $56 million and shut down in April 2022. The group plans to build a Waldorf Astoria on the property by 2027.

Meanwhile, the Crystal Bay Casino (as it is officially named), continues to pack ’em in with no big development or luxury name promises in sight.

And to many, that’s the exact recipe for success.

“I’ll say this about Roger, he figured it out,” says Crystal Bay’s Nichols. “You know, you don’t have to build a thousand units. You don’t have to do timeshares. You can just make a place where people want to come and have an evening.

“It doesn’t seem that hard.”

Crystal Bay Casino’s new GM agrees. “Our formula is simple,” says Roe. “Whether it’s easy to execute is another story. We face the same issues other businesses do. The pandemic was tough. Staffing is always hard. Finding housing is difficult. But Roger and Elise are always thinking of how to make this experience work for both customers and employees, and that’s why we stay.

“I’ve worked for a bigger hospitality corporation—believe me, I know the difference.”

Andy Frasco & the U.N. fires up a festive crowd in the Crown Room, photo by Ryan Salm

The Normans are an anomaly, not just on the North Shore but in Northern Nevada. Theirs is the last non-corporate casino in the Tahoe Basin, and they are the last couple to run their own show in the region.

“I hope you say something about the rich guys and what they’ve done to this area,” says Mitch Korcyl, a Vacaville-based self-confessed music and Crown Room aficionado. He and his partner Joanie Vevoe are up on a recent early-spring weekend to enjoy the sounds of Boulder, Colorado-based jam band Leftover Salmon, along with some of the CBC’s other amenities.

“We ate here at the steakhouse last night before the show—probably the best filet I’ve had. … You know, you can build condos, timeshares—a shrine to the wealthy, I don’t care. People still need a place to go, to hear live music, to feel a little human again,” says Korcyl. “That’s not too much … I don’t think. No, that’s not too much to ask.”

And as other lights have dimmed and the Crystal Bay corridor remains in transition, one marquee—the unlikeliest of the lot—will remain lit up on its 20th (re)anniversary on August 1, 2023.

“For a place that relies on music and crowds the way we do, the last few years have been tough,” Roe says. “But we’re going to have great shows this summer, and no matter what else happens here, we [can] control that.

“We’ll do what we can to keep our lights on.”

Andrew Pridgen lived in Incline Village before moving to the Central Coast a decade ago. He still visits the CBC whenever he’s in North Lake Tahoe whether there’s a show or not.

No Comments