22 Feb A Giant Problem for the King of Trees

Sequoias have thrived for thousands of years in the forests of the Sierra Nevada, but these ancient giants face new dangers that threaten their reign

It is a clear, crisp day in mid-December, and I am visiting the northernmost sequoia grove in California, located in a remote patch of conifer forest outside the small town of Foresthill. Sunbeams filter through the thick forest canopy onto a thin layer of snow covering Mosquito Ridge Road, revealing that no one has visited the area since the latest storm.

The Placer County Big Trees Grove is one of approximately 68 sequoia groves in the world, all of which occur on the western slope of the Sierra Nevada between roughly 4,600 and 7,000 feet in elevation.

While the trees in this tiny grove—about an hour-and-a-half drive from Lake Tahoe—are not huge by old-growth giant sequoia standards, Sequoiadendron giganteum, or simply “big tree,” as John Muir called them, are the most massive trees on the planet. The largest by volume, the General Sherman, located in the Giant Forest of Sequoia National Park, is 275 feet tall and some 36 feet in diameter. It is about 2,200 years old, meaning the tree was a sapling when Julius Caesar began his march across the Rubicon River toward Rome.

The General Sherman, at 36 feet in diameter and 275 feet tall, is the largest sequoia on earth by volume, courtesy photo

And the General Sherman is far from the oldest of its kind: Sequoias are the third-longest-living tree species in the world, with the oldest specimens taking root over 3,200 years ago in the Converse Basin Grove of Giant Sequoia National Monument.

But while these colossal trees have managed to not only survive, but thrive through countless droughts, blizzards and fires over the millennia, their existence has perhaps never been in greater peril.

Scientists estimate that approximately 20 percent of the naturally occurring sequoias in the Sierra Nevada have burned in wildfires in the past two years alone. The sheer number of trees lost in such a short period is a disheartening and shocking development, particularly given that sequoias rely on fire to reproduce. But the sort of high-intensity wildfires that have wreaked havoc throughout the American West in recent years are like nothing the sequoias have ever experienced.

“The fires these trees have evolved with are not the fires we see burning today,” says Garrett Dickman, a wildfire botanist with Yosemite National Park. “The fuels around these trees are drier and the fuel loads are way higher than these forests have ever seen before.”

Wildfires aside, sequoias are beginning to show the effects of a changing climate as well. With rising temperatures and less water in the form of snowmelt, the trees are thirsty and stressed, and thus more susceptible to the ravages of bark beetles.

“If you go through the old literature on giant sequoias, you cannot find a single instance of a tree being killed by an insect,” says Nathan Stephenson, a scientist emeritus with the U.S. Geological Survey and one of the foremost experts on sequoias. “It may have happened, but it was so rare that no one had ever seen it.”

It is happening now. Stephensen has counted dozens of old-growth trees in Sequoia National Park that have succumbed to the elements in the past decade—an occurrence he had seen only twice in his previous 35 years of observation.

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature has listed sequoias as endangered due to their dwindling numbers. The U.S. Endangered Species List has them categorized as threatened, and new consideration may be underway after the recent devastation that has forest scientists on high alert.

A Symbol of the Sierra

Muir called sequoias “kings of the forest, the noblest of a noble race.” But while the surreal size of the trees immediately stands out to any observer, their beauty is more subtle, according to Muir. He attributed the sequoia’s aesthetic appeal to its fibrous and reddish bark, and the foliage distributed in flourishes of massed clumps near the top of the tree. Some have likened sequoias to enormous pieces of broccoli because of the clumped foliage and smooth, branchless trunk, as typically about 100 feet separate the first branch from the ground in full-grown trees.

“So harmonious and finely balanced are even the mightiest of these monarchs in all their proportions that there is never anything overgrown or monstrous about them,” Muir wrote. “Seeing them for the first time you are more impressed with their beauty than their size.”

Four of the six giant sequoias in the Placer County Big Trees Grove, located near the town of Foresthill in the Tahoe National Forest, courtesy photo

Muir’s description is especially true of the Placer County Big Trees Grove, which are the nearest old-growth sequoias to Tahoe, and the most removed grove from the behemoth specimens to the south. The grove consists of only six trees, four of which are arranged at the bottom of a bowl-like declivity that is spangled with towering sugar pines, old-growth lodgepole pines, robust incense cedars and the occasional Douglas fir. A fir immediately adjacent to the four sequoias is actually the thickest tree in the bunch and could trick unpracticed observers into thinking it was the tree they came to view.

The path then bends around two large sequoias, both of which fell during a windstorm in 1861, to a view of the first of two fine specimens, including the Joffre Tree. Farther along the trail, the true prize comes into view—the Pershing Tree—situated on a high ridge with deep gorge-like valleys fanning out as far as the eye can see.

The distribution of sequoias in the remote grove reveals an unusual and mysterious trait about the tree in that, unlike most other conifers, these rare behemoths grow exclusively in clusters.

“Isolated sequoias, boy, they are not common,” says Stephenson. “They are confined to these little places. They only cover about 27,000 acres total in the Sierra, which is the size of a reasonable-sized city.”

While Muir speculated that sequoia distribution was based on glaciation, Stephenson says it likely has more to do with water access.

“They are usually found in the wettest spots between about 5,000 and 7,000 feet of elevation,” he says. “A thousand gallons a day in the summer for a single big tree is not uncommon.”

A giant sequoia grove burns in the KNP Complex Fire, photo courtesy National Park Service

Death by Fire

While giant sequoias are incredibly adaptive, the fact that they are restricted to select pockets of a single mountain range is cause for concern. These anxieties, which trace back to the late nineteenth century when Muir was tramping through the forest, have escalated since a series of high-intensity fires ripped through sequoia groves the past two years.

The Castle Fire, sparked by lightning in the summer of 2020, scorched roughly 170,000 acres, burning into about 20 sequoia groves and destroying as many as 10,000 mature trees, representing about 10 percent of the total population. Much of the damage occurred on the southern end of Sequoia National Park as heavy fire moved through the Mountain Home Grove, the second-largest sequoia grove behind the Giant Forest.

Sequoias are no stranger to wildfires. In fact, they have evolved to not only coexist, but to rely on fire, which is needed to open the tree’s small cones, allowing the seeds to fall into the soil and germinate.

But something has changed in the last decade. Whereas wildfires in the Sierra historically crept along the ground, clearing out brush while helping sequoias proliferate, the overgrown, fire-suppressed forests of today provide ample fuel that leads to far more destructive blazes.

“More recently, we have seen fires with flames that are 300 feet tall,” Dickman says. “That’s as tall as the sequoias.”

The Castle Fire galvanized the land managers in the Sierra to realize that forest thinning, controlled burning and other techniques aimed at reducing fire severity were urgent, says Christy Brigham, chief of resources management and science at Sequoia National Park.

“In the late 1800s, we started over a century of fire suppression in the forests of the Sierra Nevada, and it has led to the conditions today where we are struggling, particularly in the Southern Sierra, to keep pace in performing the fuels reductions that are needed,” Brigham says.

Illustrating her point, Brigham hadn’t even finished her accounting of the Castle Fire damage before another round of equally harmful wildfires struck sequoia habitat.

A firefighter inspects a burned sequoia during the KNP Complex Fire, which killed thousands of the ancient trees in 2021, photo courtesy National Park Service

“Our process to validate the losses in the Castle Fire was interrupted by the KNP Fire,” she says.

Sparked by lightning, the KNP started in September 2021 and torched 88,000 acres, the vast majority of which occurred in Sequoia National Park. The situation got so dire that firefighters wrapped some of the largest and most famous sequoias in foil wrapping, hoping to protect the trunks of the trees.

“Out of all the techniques we used, it was the least effective,” Dickman admits.

But it’s an indelible image. At one point in October, California Governor Gavin Newsom visited Sequoia National Park, where he delivered a televised speech standing in front of the mightiest trees on earth wrapped in industrial-grade tinfoil.

“It’s not just intellectual, it’s emotional,” Newsom said during his speech. “My dad took me to see General Sherman when I was a kid, and I hope to bring my own kids to see it one day.”

Adding to the carnage of the 2021 fire season, the Windy Fire also struck Sequoia groves hard, burning trees in the Sequoia National Forest and on the Tule River Indian Reservation.

“I just remember feeling very shocked. We are talking about the destruction of trees that have been standing for thousands of years,” says Dickman. “Sometimes I had to pull over and just kind of reset.”

In total, 27 groves were impacted by the two fires, adding to the losses suffered in the Castle Fire the year before.

Brigham is careful to note that a true tree-by-tree survey of the burned areas has yet to be completed and the National Park Service is relying on satellite imagery to estimate the severity of the fires and the likelihood of tree survival. But she does not expect a large discrepancy between estimates and the final count.

Updated estimates, which are not complete, indicate there are fewer than 80,000 naturally occurring sequoias remaining in the Sierra Nevada.

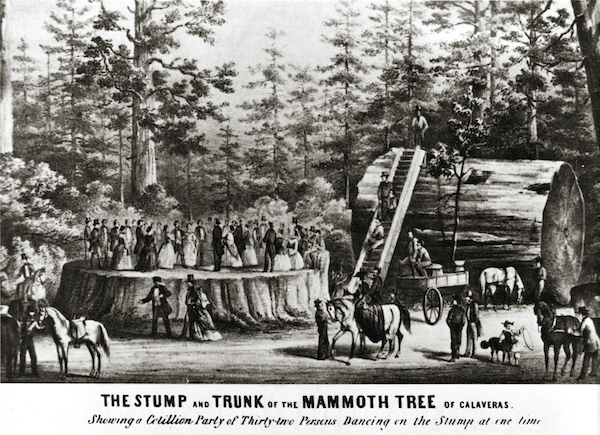

A lithograph shows a party of 32 people dancing on the stump of the Discovery Tree near the town of Angels Camp, courtesy image

The Discovery Tree

The forests that Muir grew to love were far healthier than they are today. But while Muir did not have to worry about the effects of climate change and record-setting wildfires, he did have reason to fret about one legitimate sequoia killer—logging.

Because the vast majority of millennial sequoias are under federal and state management, the rapacious loggers of that era no longer pose a threat to Muir’s beloved big trees. Even in Muir’s day, it was quickly realized that sequoias had little timber value, due to the brittle nature of the wood and its propensity to shatter upon hitting the ground when felled.

But that didn’t stop people from cutting them down.

It is, of course, somewhat ridiculous to talk about the discovery of sequoias by Europeans, since native tribes had been living alongside the noble giants since time immemorial. But Augustus Dowd, a hunter and trapper active in the Sierra Nevada, is generally credited for discovering a large grove of sequoias near a timber camp in what is today known as the Calaveras North Grove, near the foothill town of Angels Camp.

The Discovery Tree, as it was called then, earned headlines in the newspapers of the American West, with the florid writers of the day dubbing the tree the “Sylvan Mastodon” and the “Vegetable Monster.”

Sadly, ironically and perhaps inevitably, the Discovery Tree was cut down by five lumberjacks a year later. It took them 22 days of steadily puncturing the ancient tree before it fell.

Muir, as one can imagine, was unimpressed.

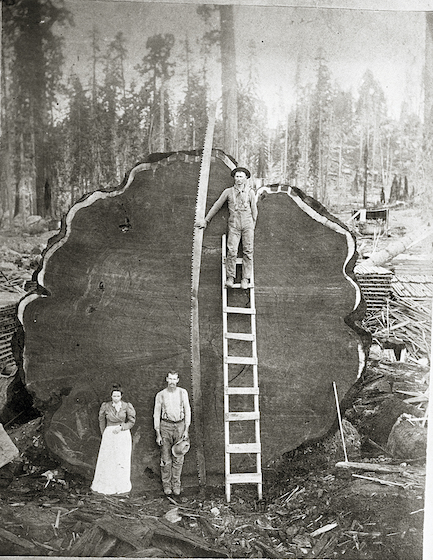

A logged sequoia in the Converse Basin Grove of Giant Sequoia National Monument, where some of the oldest trees live up to 3,200 years, photo courtesy National Park Service

He wrote an essay called The Vandals Then Danced Upon the Stump to castigate the many citizens who held a dance party on the stump of the needlessly killed tree to celebrate the novelty of the discovery.

“God has cared for these trees, saved them from drought, disease, avalanches, and a thousand storms,” Muir wrote. “But he cannot save them from sawmills and fools; this is left to the American people.”

Logging of sequoias began in earnest in 1856 and continued through the 1950s, though much of the intense logging was restricted at the end of the nineteenth century. However shortsighted the cutting of old-growth sequoias appears now, the practice helped pave the way for environmental conservation.

The Yosemite Land Grant, signed in June of 1864 by President Abraham Lincoln, called for the preservation of 39,000 acres in the Yosemite Valley by deeding the land to the state of California. It was done for the express purpose of protecting the Mariposa Grove.

Thus, eight years prior to the creation of the country’s first national park (Yellowstone), the land grant proved that Yosemite was not created to protect the sheer granite cliffs or its picturesque waterfalls, as is commonly understood, but was to preserve the stunning grove that boasts more than 500 giant sequoias.

The Yosemite Land Grant of 1864 is one of the earliest examples of a state or national government selecting a natural area for protection against the depredations of natural resource extraction.

Therefore, it could be argued that sequoias are the foundation of the National Park Service and Sierra Club and the principles that continue to undergird all environmental conservation in the United States and beyond.

Renewed Urgency

While sequoias have greatly benefited from their environmental protections, there is still reason for concern.

“What is in danger are the big old ones—the millennial sequoias that people love and travel from all over the world to come and see,” Stephenson says.

Brigham, however, says the abrupt eradication of one-fifth of the world’s naturally occurring giant sequoias has a bright side.

In the wild, giant sequoias require fire to open their seeds to germinate, photo courtesy National Park Service

“It has had beneficial effects, one of which is galvanizing land managers to work together and protect the remaining groves,” she says.

One of the formal ways to achieve that is the creation of the Giant Sequoia Lands Coalition, comprised of representatives from the National Park Service, the U.S. Forest Service, the Bureau of Land Management, UC Berkeley, the Tule River Indian Tribe and the state of California.

The coalition’s proposed mission is “a coordinated call to action of land management stewards … to continue the 150-year legacy of protecting giant sequoias and their ecosystems, in a new era of emerging threats associated with climate change and human interference of natural wildfire processes on the landscape.”

There is an emerging consensus that introducing frequent low-intensity fires to the landscape and engaging in forest-thinning projects will help protect Sierra Nevada forests from the ravages of large, high-intensity fires.

The problem comes down to money, as it often does.

Newsom has already committed to increased spending on parts of the forest under California control, but the vast majority of sequoia groves are under the purview of the federal government.

Of the approximately 20,000 trees with a diameter greater than 10 feet, 89 percent of them occur in lands managed by the federal government, whether national parks or national forests, according to the National Park Service. So the burden largely falls on the federal government to allocate scarce resources to Sierra forests. Portions that have already received attention show positive signs of success.

“Areas where there is fuels treatment, like the Merced Grove in Yosemite, for instance, have fared drastically better,” Dickman says.

Yosemite National Park has been conducting controlled burns in the Mariposa Grove, arguably the second-most famous sequoia grove in the world after Giant Forest, since the 1970s, when the consensus around fire suppression first began to shift.

“The Mariposa Grove is in a pretty good place,” Dickman says. “But the areas around it need help.”

Tom Vilsack, the head of the U.S. Agriculture Department, which oversees the U.S. Forest Service, visited California along with Vice President Kamala Harris in January, and the pair touted the $2.4 billion dollars the Biden Administration has allocated for hazardous fuels management across the American West.

Specific to the forests of California, Biden designated $600 million for disaster relief. Vilsack recently revealed a plan, not funded as of yet, to treat 20 million acres of forest service lands, with another 30 million acres to be treated on other federal lands, including those managed by national parks or tribes.

“If we play our cards right, these sequoias will be around for another 2,000 years,” says Brigham.

While Brigham remains optimistic, fire is only one of myriad threats that loom over sequoias, most of which have only emerged in recent years.

Immortals No More

“I never saw a Big Tree that had died a natural death,” Muir wrote about sequoias in 1894. “Barring accidents they seem to be immortal, being exempt from all the diseases that afflict and kill other trees.”

Muir went on to write that he has seen trees smashed by lightning, burned by fire or cast down by gusty storms, but has never seen one die in the way other trees succumb to disease or depredations from various pests.

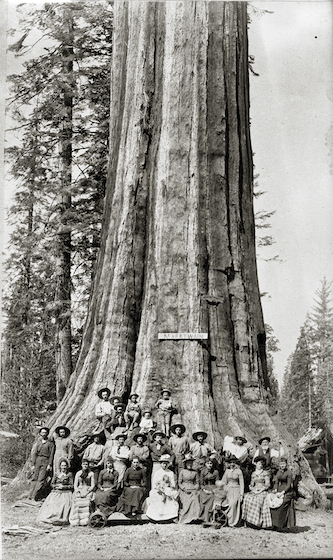

Visitors gather for a photo in front of a giant sequoia named the Mark Twain tree, which was later cut down, photo courtesy National Park Service

Stephenson, who began his career studying sequoias in the late 1970s, would have generally agreed with Muir’s observations if asked about it in 2013. But more recently, the story has altered.

“In 2014, I saw a sequoia that had foliage dieback, probably due to prolonged drought,” Stephenson says. “There was no record of this happening in any of the previous droughts that struck the Sierra Nevada.”

Specifically, Stephenson is familiar with the work of former conservationists dating back to 1925, when a severe drought hit California and lasted through 1927. While the naturalists of the time were writing about drought effects on opossums, not one noted any adversity among the sequoia groves.

But in 2014, during the nadir of the dry spell that began in California in 2011 and continued through 2017, Stephenson noticed the sequoias were starting to appear beleaguered.

“Until 2014, I had been closely observing sequoias for 35 years and I only saw two dead on their feet,” Stephenson says. “But I began to see it more and more. In 2018, I counted 33 sequoias dead on their feet within the boundaries of Sequoia National Park alone.”

The scientist says losing 33 sequoias was not in itself cause for concern. “I was worried about what it may portend,” Stephenson says.

Namely, the message appeared to be that sequoias were water-stressed. They are thirsty trees that require voluminous amounts of water, but the more concerning proposition was that sequoias are now so parched that they are increasingly struggling to fight off the damaging effects of the bark beetle, which has killed scores of conifers in the Sierra Nevada.

Now, due to the rising temperatures and lower precipitation in California, bark beetles are starting to kill these hardy trees. More concerning is the fact that old-growth sequoias, with trunks at least 4 feet in diameter, seem to be more susceptible to the damage.

“This wimpy beetle is suddenly able to take out these huge sequoias,” Stephenson says.

And while a decrease in water availability is a primary factor, here, too, fire plays a role.

“All of the trees I saw dead on their feet had scorching at their base, which means their conductive tissue burned part way at the base, making it more difficult for the trees to transport water,” Stephenson says.

Unlike fire management, if beetles are suddenly able to kill giant sequoias due to persistent drought conditions, there are not many solutions in the offing.

“I am concerned because there is a potential for these trees to be in trouble,” Dickman says. “It’s not a great trajectory right now, but I do think it’s all recoverable if we can get things to level off.”

Sequoias at Benmore Botanic Garden near Dunoon in Argyll, Scotland. Planted in 1863, the trees are more than 160 feet tall, photo by Dougie Macdonald

Globally Embraced

Although thousands of mature sequoias have burned the past two years, the species is not in danger of extinction, says Stephenson, noting that the trees have been planted all over the world outside of their natural habitat.

The tallest sequoia ever recorded outside of the United States was planted near the town of Ribeauville in northeastern France in 1856 and measured 191 feet in 2014. One specimen that was planted in Italy has reached a height of 72 feet in 17 years.

Sequoias do not grow well in climates without temperate winters, like the eastern United States, but they can be found throughout the West, especially in cities like Portland, Seattle and Reno. A giant sequoia stands as a prominent landmark in downtown Seattle, marking the entrance to the city’s downtown retail corridor, while several large sequoias dot the University of Nevada, Reno campus.

While there are no naturally occurring sequoias in the Tahoe Basin, one particularly tall tree on the Nevada side of the Cal Neva property in Crystal Bay is a healthy example, as are numerous other trees on both shores of the lake.

One of the notable features of the Placer County Big Trees Grove is the numerous sequoias that have sprouted—and thrived—since they were planted by the Auburn Lions Club in 1954. The plantings have caused mild controversy, with some saying the unnatural introduction may taint the genetic purity of the naturally growing trees in the grove.

The debate invokes a relatively new concept in biology called assisted migration, which sequoia managers have bandied about in research papers and discussions in recent years.

Assisted migration describes the act of moving plants or animals to different habitats that may be more conducive to their survival. For sequoias, as temperatures increase, scientists wonder if moving them up in elevation may be better for their long-term health.

Sequoias tower over the Giant Forest Museum near the southern entrance of Sequoia National Park, photo courtesy National Park Service

“When I was younger, I visited these private cabins in the Mineral King Valley where sequoias had been planted on the property,” Stephenson says. “I recall them looking pretty beat up, because at about 8,000 feet in elevation, the winters are too cold for them.”

But things have changed.

“These days, those trees look pretty darn healthy,” Stephenson says.

The contemplation of whether to help sequoias adapt to a warming planet has potentially large implications for Lake Tahoe.

Though sequoias do not occur naturally in Tahoe, there is no reason they could not subsist at lake level (approximately 6,300 feet) or higher. Moreover, if global temperatures continue rising at the current pace, 8,000 feet or even higher might be a more amenable habitat for sequoia groves in 20, 50 or 100 years, let alone the 3,000-year time horizon of the tree’s lifespan.

“It’s only in the idle discussion phase right now,” Stephenson says of the possibility.

But wildlife managers are already doing assisted migration with certain trout species that are being moved upstream to cooler portions of water.

“It’s an idea we have been talking about in the parks, about moving trees up in elevation in some of the burned areas,” Brigham says.

But Brigham adds that the National Park Service is more about conservation and preservation of the forest, and ideas like assisted migration may work better in the context of the U.S. Forest Service, where active management of the forest is more of an operating principle.

“It’s not an uncommon idea in the national forest system, where we are used to moving things around,” Stephenson says.

If pursued, Lake Tahoe, which is well within the sequoia range and under forest service management rather than the National Park Service, might be an ideal location for sequoia groves. Some impressive sequoias are already growing on private properties, and there would likely be no shortage of willingness among residents and visitors to the Basin to incorporate the magnificence of the most massive conifers on earth into an area where logging has long since removed old-growth forests.

For now, such discussions are purely academic and speculative, but given the rate that sequoias have perished in recent years, for these trees to continue to serve as marvels for generations to enjoy, they may need help adapting to the vagaries of a rapidly shifting natural world.

All the scientists interviewed for this story agree that diligence and open minds are required if children in 1,000 years are to be able to come to the Sierra Nevada and join John Muir in saying: “Do behold the King in his glory, King Sequoia! Behold! Behold!”

Matthew Renda is a former Tahoe resident who now lives in Santa Cruz.

No Comments