19 Feb A Lifeline for the Whitebark Pine

As one of the Lake Tahoe Basin’s hardiest trees fights for survival, forest scientists hope a proposed listing under the Endangered Species Act can boost the whitebark pine’s recovery

Hikers who find themselves on the wind-blasted ridge of Dicks Pass can be forgiven if the main attraction upon arrival is the peerless view of the dramatically unfolding landscape below.

Whitebark pines dot a rocky slope off of Dicks Pass in Desolation Wilderness, photo by Sylas Wright

Velma Lakes dapple the forested terrain to the north. Emerald Bay and Lake Tahoe glimmer with bright blue hues to the east. And looking south, Lake Aloha captures a glint of the sun at the foot of Pyramid Peak as the spine of the Sierra runs toward its zenith.

But there also, just off the rocky trail, is a smaller story unfolding that is no less spectacular if one pays attention.

It is the story of the whitebark pine.

But that story grows more fraught as climate change, development and other perils encroach upon the tree that makes its home among the elevated heights of the Lake Tahoe Basin.

“Creatures like birds can adapt to climate change, but trees, they are stuck,” says Will Richardson, executive director of the Tahoe Institute for Natural Science.

None more so than the whitebark pine.

The stunted and wind-contorted pine trees thrive in a harsh subalpine climate where gale-force winds are common and the snow loads are often copious throughout the winter. In the Tahoe area, they are rarely found below 8,500 feet in elevation, says Richardson.

At the highest elevations of their range, whitebark pines appear as shrubs, or krummholz, such as this example on Pywiack Dome in Yosemite National Park, photo courtesy Jarek Tuszynski

For hikers and peak baggers, the whitebark pine is typically the last tree standing at the highest reaches of their destination. For instance, when ascending 10,886-foot Freel Peak, the highest point in the Lake Tahoe Basin, one can marvel at the gnarled krummholz of whitebark pines in scattered clumps just before emerging above the tree line. It’s an encouraging sign that the summit is near.

“Krummholz is a term that describes their stunted, deformed look,” says Rita Mustatia, a silviculturist with the Lake Tahoe Basin Management Unit.

On Freel Peak, the plants appear to be meager shrubs hugging the rocky mountainside, but they are actually old trees.

“They grow very slowly and it takes a long time to get big,” Mustatia says. “If you see one that is between 12 and 15 feet, it means that it’s about 100 years old.”

The tree’s protracted maturation process further means individual whitebark pines take decades before they are able to grow seeds for distribution, meaning they aren’t able to repopulate as quickly as trees with more abundant habitat.

“Think of them as a sky island,” Richardson says. “They are up there in terms of both elevation and latitude and seed dispersal becomes a real problem.”

Whitebark pines are reliant on the Clark’s nutcracker to disperse their seeds, photo by Robert Klinger, courtesy USGS

A Symbiotic Relationship

The whitebark pine has evolved to solve this dispersal problem by forging a relationship with the Clark’s nutcracker that operates as an epitome of the biological concept of symbiosis.

“Seeds from the whitebark pine cones are the main source for the Clark’s nutcracker, and the bird is the reason the seeds get dispersed, for the most part,” Mustatia says.

The nutcracker, a small gray bird with black wings, spends most of its time at tree line in the mountains of the American West, including Lake Tahoe. In order to survive the harsh winters, the bird stores its main food source —pine seeds —in various caches in the subalpine ecosystem.

“The bird is absolutely amazing at remembering where these caches are,” Richardson says. “It has the best spatial memory of any vertebrae.”

But in some cases, the bird may cache a surplus, or perish, and even the best memories are capable of lapses, all of which allows the whitebark pine seeds to germinate and eventually grow.

“You rarely see a single whitebark pine. They grow in clusters because they come from multiple seeds in the cache,” Mustatia says.

It’s also why the trees grow, somewhat counterintuitively, on the windward side of the mountain, because the birds put their caches in the wind-scoured parts of the snowpack that aren’t as deep as the drifts on the other side of the ridge.

To compensate, the whitebark pine has evolved to be hardy, perseverant. But now, despite their legendary persistence, they’re in trouble.

A cluster of twisted whitebark pines in the Mount Rose Wilderness, photo by Sylas Wright

Seeking Federal Protection

On December 1, 2020, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposed listing the whitebark pine as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act. The trees have qualified for listing since 2011 but have been passed over repeatedly for species that warrant a higher priority.

It’s called “warranted but precluded” in agency vernacular.

But December’s announcement shows that wildlife officials in the federal government are beginning to take notice of how imperiled the whitebark pine actually is.

“I think the fact that a species that occurs across 80 million acres of the American West is at risk of extinction is profound,” said Noah Greenwald, an attorney with the Center for Biological Diversity, the organization that asked the species to be listed, in 2011. “It highlights what is at stake with climate change.”

The Fish and Wildlife Service will take public comment for 60 days, schedule a hearing if warranted, after which they will decide whether to make the proposed listing final.

Although the agency mentions climate change as one of the contributing factors, it says the most important factor in the decline of whitebark pine throughout the American West is a fungus native to Asia that has proved particularly pernicious to white pines in general.

“We have determined that the primary stressor driving the status of the whitebark pine is white pine blister rust, a fungal disease caused by the nonnative pathogen Cronartium ribicola,” the agency wrote in its proposed rule published to the federal register.

Blister rust’s deleterious effect is not relegated to the whitebark pine. The fungus attacks all species of white pine in the Lake Tahoe Basin and beyond. Around Tahoe, that means the beloved sugar pine and stately western white pine are also susceptible to the ravages of the nonnative fungus.

“You can see the impact just walking around the forest, especially if you are aware of the problem,” says Maria Mircheva, executive director of the Tahoe-based Sugar Pine Foundation.

A sugar pine towers over a forested landscape in the Lake Tahoe Basin. The sugar pine is one of three white pine species in the Basin, all of which are susceptible to blister rust infection, photo by Tom Lotshaw, courtesy TRPA

Imperiled White Pines

The three species of white pine in the Tahoe Basin are found, generally speaking, in different layers of elevation, with the whitebark pine occupying the highest strata and the western white pine just below that, occasionally appearing as high as 9,000 feet, Mustatia says. The sugar pine overlaps with the western white but also flourishes at lake level, meaning it has a wider distribution throughout the Lake Tahoe region.

In all three species, the evidence of blister rust infection begins with a dead branch or two, usually toward the top of the tree.

“The progress typically begins in the needle and goes to the branch. Once it reaches the trunk it girdles,” Mircheva says. “In a pine tree, once the top dies, the whole tree dies.”

Girdling, also called ring-barking, is a process in trees where the bark is removed from the entire circumference of the trunk or a branch. Its presence in white pine is essentially a death sentence.

Blister rust affects all three of the white pine cousins, but the sugar pine and western white have proved more resilient.

“Everywhere we look around the Basin, the sugar pine has obvious signs of rust, but it’s not as concentrated as what we find in the more pure stands,” Mustatia says.

While sugar pine and western white are mixed in with other conifers and some deciduous trees such as aspen, the whitebark pine has an ecosystem to itself.

“At the higher elevations, more spread is possible and it’s more severe,” Mustatia says.

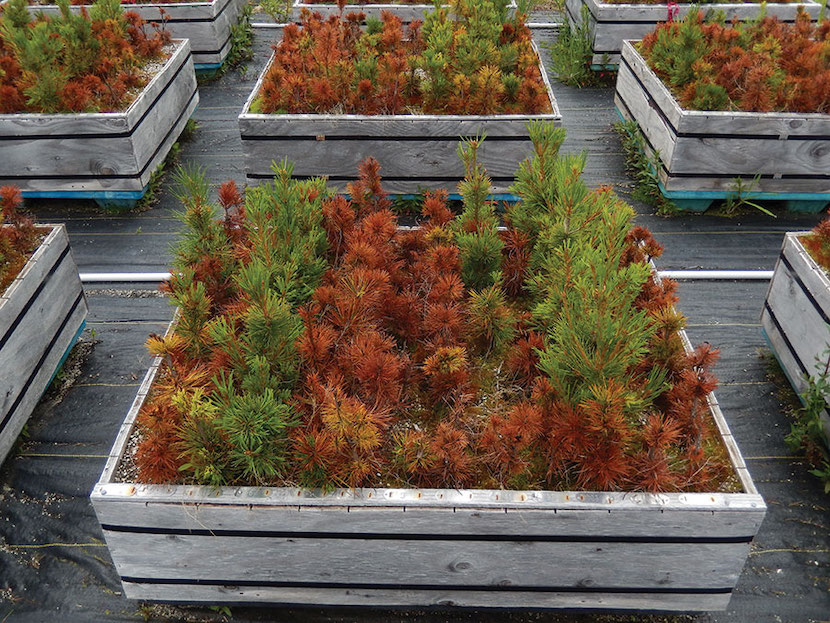

Whitebark pine seedlings show a large variation in blister rust resistance at Dorena Genetic Resource Center in Oregon, photo by Richard Sniezko, courtesy USDA

Genetic Resistance

Another detriment the whitebark suffers relative to its peers is genetic. While all three trees have seen their genomes sequenced, scientists have identified genes in both the sugar pine and the western white that are resistant to blister rust.

“There is a source of resistance in whitebark pine, but it isn’t just one gene like in the sugar pine, but a combination of genes,” explains Arnaldo Ferreira, a tree geneticist with the U.S. Forest Service.

At present, scientists at the Dorena Genetic Resource Center in Cottage Grove, Oregon, are working to identify which combination and sequence of genes in the whitebark pine provide resistance to the blister rust. But the process is expected to take years.

“The single-gene resistance is faster to identify, faster to implement,” Ferreira says.

Thus, in areas where there is tree die-off, organizations like the Sugar Pine Foundation are able to use sugar pine seeds with genetic resistance to the invasive fungus to carry out restoration projects.

“Our newest project is trying to reforest the burn scar left over by the Loyalton Fire,” Mircheva says.

The Loyalton Fire burned over 47,000 acres of forest near Hallelujah Junction north of Tahoe in the summer of 2020. Many areas of the forest are so remote, the Sugar Pine Foundation has employed drones to drop plantings, or hockey puck-shaped objects full of dirt and sugar pine seeds.

So there is not only hope for the near-term prospects of the sugar pine and western white pine, but forests are actively being regenerated with genetically resistant plants.

In the lower elevations of their range, whitebark pines mix with other conifers such as lodgepole pine, red fir, mountain hemlock, Sierra juniper and the related western white pine, photo courtesy Quinn Lowrey

Hope for the Whitebark Pine

The whitebark pine’s immediate and long-term future is cloudier. For reforestation plans to be an option, genetic resistance must first be identified in order to expedite restoration efforts.

Furthermore, the specter of blister rust threatens the whitebark pine because climate change is harder on the species.

“Long-term scenarios, one could envision trees currently at lower elevations moving up due to warming temperatures and potentially outcompeting the whitebark pine,” Mustatia says.

Climate change also means more intense droughts and for longer periods, creating water stress for the plant species.

“Drought affects all trees, rendering them less able to fight off disease, insects, not to mention fires,” Mustatia adds.

The mountain pine beetle, which also preys on the trees, has seen its reproduction cycles accelerate due to warmer temperatures, Mircheva notes.

The tree, therefore, must stave off a number of imminent threats if it is to retain its post high along the serrated ridges of the Sierra Nevada.

But scientists and endangered species advocates are hopeful an imminent listing under the Endangered Species Act could help.

“The listing puts more research and resources behind the efforts to combat blister rust, identify resistant trees, raise them and plant them,” Greenwald says.

A listing would also protect them from mountaintop development.

“We need to pay attention to these mountaintop communities,” Richardson says. “They may seem like they are out of harm’s way, aside from the occasional cell tower or ski lift. There may not be a lot of development on mountaintops, but these are highly specialized and often very fragile communities of organisms and they deserve our attention and protection.”

Matthew Renda is a Santa Cruz-based writer and former Tahoe resident.

No Comments