27 Nov Counting the Snow

The Central Sierra Snow Lab has quietly measured precipitation totals for more than 75 years, creating a long-range set of data that’s invaluable for climate research. Now, a new leader is ushering the historic lab into the future

The Central Sierra Snow Lab has seen many big winters over the past seven-plus decades, including 2022-23, photo courtesy CSSL

On Donner Summit, in the middle of last winter, deepening snowbanks appeared to swallow the Central Sierra Snow Lab. Only the uppermost windows of the three-story-tall A-frame were visible. A steep pathway dug into the snow led down to the front door, which in dry months is located up a set of stairs, on the second floor of the building. It was out of that door that Andrew Schwartz emerged every day that dawned with new snow, keeping a longstanding ritual at the Central Sierra Snow Lab humming.

A pathway with steps dug into the snow leads to the lab’s front door during the big 2022-23 winter, photo courtesy CSSL

Schwartz, 38, is the lead scientist at the Central Sierra Snow Laboratory, a research facility run by UC Berkeley that has measured every inch of snowfall on Donner Summit since 1946. Schwartz holds a PhD in atmospheric science from the University of Queensland in Australia. In the Australian Alps, he was studying the impacts of wildfires on the snowpack and the connection between atmospheric rivers and rain-on-snow events when he saw a job posting to run a little-known snow research center on Donner Summit, where it so happens the mountains are also heavily influenced by wildfires, atmospheric rivers and rain-on-snow events. He took the job and moved to the other side of the world, where he would soon experience the deepest, heaviest winter of his life.

By the middle of last March, the train of winter storms had become repetitive, and life at the Central Sierra Snow Lab began to feel like the movie Groundhog Day. “It was physically and mentally trying at times,” Schwartz says.

First thing in the morning, Schwartz would head outside with a set of rulers and a hollow metal tube and trudge through the snow to a platform in the backyard, where scientific instruments are mounted on towers. At 8 a.m. sharp he’d push the ruler into the fresh snow and measure down to a board he’d placed the day before, then note how much snow had fallen overnight. Next, he’d collect samples of snow in the metal tube to measure the water content.

Schwartz took these measurements in the morning and afternoon every day there was new snow, keeping alive a set of data that runs back more than three-quarters of a century.

An Old Lab Gets New Blood

The longevity of the Central Sierra Snow Lab measurements adds up to one of the most valuable sets of data in the country, if not the world, to identify long-range patterns in the snow. The data is a testament to climate change and the scarcity of water in California.

There are few labs that have collected such incremental data, inch by inch, year by year, for so long. The Central Sierra Snow Lab is often compared to the Mauna Loa Observatory, where researchers have recorded daily levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere since the 1950s—a data set known as the Keeling Curve, which shows carbon dioxide levels increasing exponentially. Related, the snow lab’s data show that winters in the Sierra are trending warmer, with more precipitation falling as rain than snow.

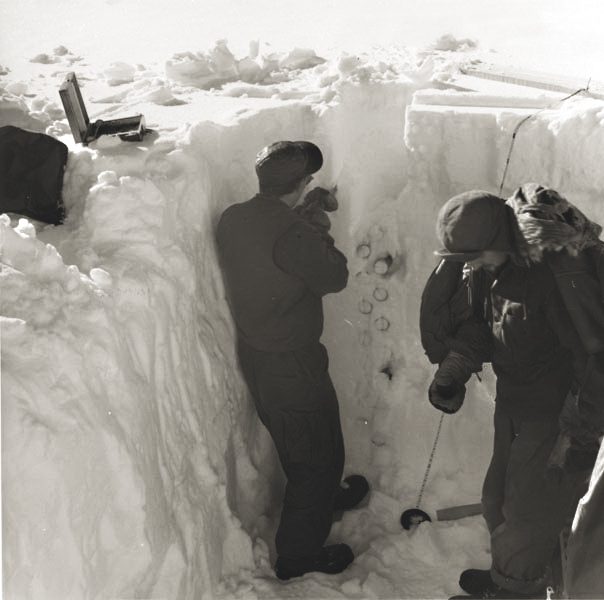

Snowpack density studies at the lab in 1949, photo courtesy Donner Summit Historical Society

For decades, the snow lab collected this data quietly, without publicity or fanfare. The obscure lab, located hundreds of miles away from the nexus of UC Berkeley, was hardly known, even by people who studied the snow. Schwartz didn’t know the lab existed until he saw the job listing.

Originally from Colorado, Schwartz has long been fascinated by the snow, which led to a career studying meteorology and the snowpack. He was finishing his doctorate in Australia when he applied for the job on Donner Summit. The position attracted him because it was field work, located not inside a classroom but in the middle of the woods. He would also have time to spend with students visiting the lab for field trips or for university research, and he could continue his work monitoring and studying the snowfall. In the spring of 2021, he moved to Donner Summit to live at the Snow Lab with his wife and their two dogs.

In the more than seven decades since the lab opened, operations have greatly diminished. Research continued, but the snowfall measurements were largely hidden from the public.

When Schwartz arrived, he brought with him energy and ideas to bring the lab into the light. At the top of his list was building a new website to host all the data that had been digitized, going back to 1970, so the public could freely access more than 50 years of snowfall information on Donner Summit. But first, he had to figure out how to get better Internet access, which was so slow he could hardly send an email.

Bryan Allegretto, cofounder of Open Snow, relies on the snow lab’s data to put his winter storm predictions and observations into historical context. Before Schwartz came on board, that data was kept mostly in Excel spreadsheets that he had to seek out directly from the lab. With Schwartz, the information became “completely transparent” thanks to the new website, Allegretto says.

“He continues to add more content on the website, live webcams, and he posts to social media, which gets the data out to a broader audience,” Allegretto says. “The more access to the data, the better for everyone to analyze the data and to use it for their business or personal activities.”

Humble in appearance, the Central Sierra Snow Lab looks like an old Tahoe ski lease, its limited interior space chock full of equipment, from antique meteorology instruments to snow safety gear. A sign on the second-floor entry warns that the door often jams shut. Years of heavy winters have shifted the building, just slightly.

On a fall day in 2021, Schwartz sat behind a mid-century desk, likely issued by the Forest Service in the 1950s. He wore a sweatshirt, jeans and baseball cap emblazoned with the Colorado “C.” There were no white lab coats. Schwartz had been at the job for several months but was still unpacking. His doctorate in atmospheric sciences was framed and sitting in the window. The office was so cluttered from years of collecting everything from meteorology equipment to snow gear that he was still trying to find space on the wall to hang it.

Decades of Data

The Central Sierra Snow Lab was one of three laboratories in the Western United States created by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the National Weather Bureau to study snow and hydrology. In its heyday, during the late 1940s and early ’50s, the lab was staffed by seven people year-round. It contains records upon records of scientific information, much of it handwritten in red leather-bound ledgers and stored in the basement. There are cabinets full of archival photos. The lab contains so much material—it even holds snowfall records kept by the railroad dating back to the late 1800s—that Schwartz says there’s enough to employ a full-time archivist for multiple years, if only it had the funding.

A lab researcher weighs snow to determine its water content on May 5, 1948, photo courtesy Donner Summit Historical Society

In the 1950s, the U.S. Forest Service took over management of the Central Sierra Snow Lab. It’s the only one of the three labs that still operates. Research continued while the lab phased into a quieter period for several decades. Starting in the mid-1990s, UC Berkeley took it over, keeping it staffed with one person, a researcher named Randall Osterhuber, who single-handedly kept the data set alive until he retired in 2019.

When Osterhuber left, the university didn’t immediately hire a replacement. Then came the winter of 2019-20, when the snow finally arrived in March alongside COVID-19. With pandemic budget cuts looming, UC Berkeley was reevaluating the lab’s merit. At the time, Robert Rhew, an associate professor at Berkeley who worked in the atmospheric biogeochemistry laboratory, was faculty director of the Central Sierra Field Stations, including the snow lab and another Berkeley-run facility at Sagehen north of Truckee.

“Priority was being put into research centers that supported university research, whereas the snow lab served primarily to support governmental agencies and local communities in the Central Sierra,” Rhew wrote in Moonshine Ink in January 2021, adding that many people at UC Berkeley were surprised to learn the university operated a snow lab.

Rhew advocated on the lab’s behalf, speaking up for its long-standing research and the important role it plays not only in measuring the snow but assessing how much water is in the snowpack—important information for California’s water resources managers. He organized a meeting with the lab’s partners and stakeholders, convening the National Weather Service, Department for Water Resources, Desert Research Institute and several more groups in hopes of convincing Berkeley to maintain operations.

It worked. Rhew secured approval to hire a new manager to usher the lab into the future.

Even so, there’s a small gap in the snow measurements in 2020, before Rhew could bring on a temporary worker to bridge the gap between Osterhuber and Schwartz. “There will always be an asterisk for 2020 because of that,” Schwartz says.

Thrust Into the Spotlight

It’s been two and a half years since Schwartz took over at the snow lab, and he’s already accomplished much of the revitalization work he envisioned.

“You can always go into somewhere with grandiose ideas of what you’re going to do and how it’s going to work out and things like that, but there’s not always a guarantee that it’s going to,” Schwartz says. “So seeing a lot of these things that we’ve implemented come to fruition, and have the impact that we were hoping they would, has been just absolutely fantastic.”

As the snow piled up during the 2022-23 winter, an extension ladder was required for measuring the totals, photo courtesy CSSL

Thanks to Schwartz’s efforts, combined with the historic 2022-23 winter that produced 62 feet of snow, the Central Sierra Snow Lab was in the national spotlight.

When Schwartz announced in March 2023 that the season total had surpassed 1982-83, moving into second place behind only the 1951-52 winter’s 67 feet, he was interviewed by a nonstop stream of reporters from media institutions—the Weather Channel, CNN, NPR, the New York Times. Good Morning America came up to report a story on-site. It was a mind-blowing amount of exposure for a lab tucked into the woods that nearly shut its doors entirely three years ago.

“It really means a ton to us because we’ve struggled so much in getting support over the years,” Schwartz says. “We’ve had to fight tooth and nail for all the funding we can get.”

If the lab was obscure in its earlier chapters, it was now a leading voice to bear witness to the massive winter of 2022-23. And while ski resorts provide their own snow totals, Allegretto says the snow lab stands alone as the truly reliable source.

“Most of our forecasters don’t have a scientific lab measuring snowfall and have to rely on the ski areas,” says Allegretto, adding that he uses the lab’s measurements to judge the accuracy of the ski areas’ numbers.

“The snow lab is just under 6,900 feet [in elevation] while most ski areas are measuring at 7,000 feet or higher,” Allegretto says. “So in warmer storms, [the snow lab] will have much less [snow] reported, especially if it rains. With colder storms it is close, and it should be very close to Sugar Bowl’s report, which is right down the street. I have used Andrew’s measurements to question some ski areas northwest of the lake that report less at a higher elevation, as that is not usual.

“So it has been very helpful having a snow lab in our backyard that reports snowfall accurately 12 months out of the year, as well as rainfall, and having all of that amazing data to analyze and relay to our users.”

A media report from the end of the season stated the lab had been cited in 3,700 news articles last winter, for a total reach—that is, how many times an article put the lab’s work in front of a pair of eyes—of 13.7 billion. During the biggest moments of the winter, Schwartz received as many as 20 media requests a day. He also penned an opinion piece for the New York Times, calling for a reprieve from the doomsday coverage of all the atmospheric river events.

The Winter That Piled Up

Last winter, the work never seemed to end. If Schwartz wasn’t counting the snow or shoveling it—he got tendonitis in his elbow while struggling to keep up—he was talking about how much snow was falling from the sky.

The media coverage benefitted the lab, alongside Schwartz’s efforts to find new sources of funding. In the last year, Schwartz secured enough funding to hire one full-time and two part-time employees. He hopes to hire another full-time employee next year.

Andrew Schwartz conducts studies at the snow lab with a young helper, photo courtesy CSSL

“For the last four decades, there’s only been one person up here,” Schwartz says. “Because of the hard work that we’ve all been putting in, and the great things happening at the lab, we’re now expanding to levels that hadn’t really been seen since the lab was in its heyday.”

The new employees will help Schwartz manage field trips and introduce students to snow science. The lab’s work has also gained recognition among snow scientists who want to collaborate.

The Central Sierra Snow Lab is still part of the nationwide network of Snotel sites—those daily measurements feed into a larger network of sites that measure snow depth. But the lab is the only site that measures snowfall manually. With some extra staff, funding and partners, Schwartz is expanding the work at the lab, along with his own research into the impact of El Niños and La Niñas on Sierra winters.

Today, Schwartz is collaborating with scientists from NASA and water resource managers across California, ushering the lab to a well-earned seat at the table for discussions about climate change, the snowpack and water reserves. At any given time, instruments are collecting precipitation data from the last 24 hours, while the lab’s website shows how deep the snowpack is and how much water it contains.

This past summer, Schwartz also finished a major infrastructure project in the backyard. It’s the biggest investment in the snow lab in decades and will help scientists develop better models to understand climate change and water runoff patterns.

And still, for all the advancements in technology, the lab’s most essential tools remain the ruler and hollow tube that Schwartz uses for snow measurements. The new technology doesn’t replace the old, he says. It all works together.

Schwartz has hardly taken a vacation since last winter. He’s been so busy installing new equipment, hiring people, writing grants, securing funding, talking with collaborators, making plans and expanding the website that spring, then summer and fall, whizzed by.

As for how he fared last winter, he says he remembers the shoveling.

Every day, he’d shovel for two hours, at least, clearing off the propane tanks and garage and digging the tunnel to the front door. And still, Schwartz says he’s excited for another snow season.

He also says the El Niño predicted this winter is a complete coin flip for the Sierra. Historically, the lab’s data shows that five of the 10 biggest snow years on record were El Niños, yet so, too, were four of the driest winters. So it’s a wash.

“The only thing I can say for sure is that we’re going to be warmer than average. And other than that, it’s anybody’s guess, really,” Schwartz says.

In between the work and the storms, Schwartz admits he found a few moments to steal away and enjoy living on Donner Summit.

“On those truly big mornings, I-80 was shut down, Old 40 was shut down, but Sugar Bowl would still find a way to open, and to just give myself some peace of mind, I would go out with my snowboard and get fresh tracks for two or three hours in the morning as a kind of meditation.”

Getting outside, riding through chest-deep powder—even when, on a few occasions, he forgot a meeting and had to call in from the chairlift—those were the days that made his devotion to snowfall worthwhile. Finally, he was able to enjoy the snow, and not just be buried by it.

Julie Brown Davis is a freelance journalist living in Reno. She, too, wakes up and checks snow totals posted by the Central Sierra Snow Lab and the ski resorts first thing in the morning.

Starr Walton Hurley. Olympian

Posted at 16:44h, 09 JanuaryThis is a wonderful story. My grandfather Oscar Jones developed Soda Springs and opened the Soda Springs Hotel in 1927. The register is at the Historical Society. I believe he was instrumental in getting the snow lab started with Dr Church. I have a cabin at Soda Springs still. A part of my growing up! Herstle Jones was Oscar’s brother and built Rainbow Tavern and Nyack. My father built the Donner Ski Ranch. Love the histo!