01 Jul Filming for Conservation

Through their Where the Wild Roam video series, two friends embark on a mission to educate the masses about preserving the natural environment

As a published author, Joe Flannery has always had a knack for descriptive storytelling—the ability to paint a vivid picture in readers’ heads through the eloquent use of words. Then he discovered an even more effective means of communicating with his audience.

A wolf captured on a camera trap last winter in Sierra Valley, 38 miles from the shores of Lake Tahoe, courtesy photo

“I quickly found that videos were a great way to reach a lot of people,” says Flannery, who, along with his close friend Kyle Lancaster, is the creator of Where the Wild Roam.

Available online for free, the video series is intended to educate the public about the vulnerability of wildlife and wild places in hopes of preserving both for future generations. The films are entertaining, informative and look to be exactly what they are: two friends who love the natural environment trying to get viewers as excited about it as they are.

“We film bunches of episodes that we call series with similar themes,” explains Flannery, who is the on-air personality and Lancaster the cinematographer. “Our California Wolf series, already filmed, will feature some locations in the North Lake Tahoe region—we caught a wolf on one of our camera traps last winter in Sierra Valley.”

‘A Conservationist at Heart’

Flannery comes to his love of nature naturally.

A native of Cameron Park near Placerville, his father served as chief park ranger for the American River Parkway and his grandfather was a ranger in Humboldt Redwoods State Park. His mother also worked in the American River Parkway.

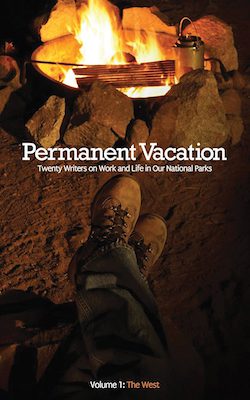

Joe Flannery is one of 20 authors featured in Permanent Vacation, published by Bona Fide Books in 2011

Flannery followed his family’s lead, becoming a public land manager for nearly 20 years after attending UC Davis, including stints in the National Park Service and U.S. Forest Service, which brought him to Tahoe City in 2009. While living in Tahoe, he enrolled in writing classes at Lake Tahoe Community College, where an instructor asked if she could submit a wildlife essay of his to a local publishing company, Bona Fide Books. His piece, “The Grizzly Country,” was accepted and published in the 2011 release Permanent Vacation: Twenty Writers on Work and Life in Our National Parks. Seven years later, Flannery was published again in Permanent Vacation, Volume 2.

Flannery’s writing skills transitioned well to his position as public affairs officer for the Tahoe National Forest, which he held from 2018 to 2021. After a successful career with the Forest Service, Flannery left at the end of 2021.

“I’m a conservationist at heart, and thought I could do more outside the federal system,” says Flannery, who now lives in Nevada City and works for a private company called Vibrant Planet.

Outside of his main job, he has a passion for what he calls his “grand experiment.” That is, “How can we educate people and also have a little fun?”

That’s where his video series—and his best friend—come into play.

‘Friends for Life’

Flannery and Lancaster met at Gar Woods Grill & Pier in Carnelian Bay, where Flannery’s now-wife worked and Lancaster was a boat valet. The two hit it off right away.

“He had just started a video production company, formerly called Rotor Collective,” Flannery says. “I was doing some nonfiction conservation writing. Kyle asked me—actually at the Lost Sierra Hoedown—if I had any story ideas that could translate to video.”

Joe Flannery, left, and Kyle Lancaster with their daughters, courtesy photo

That conversation led to the award-winning documentary The Last Herd, which tells the story of the last wild herd of bison in the Henry Mountains of Utah. The film, which the pair independently produced and wrote along with their friend Ryan Fitzhenty of Tahoe City, was featured at the 2019 Wild & Scenic Film Festival.

“We’ve been friends ever since,” says Flannery. “When you spend a few weeks in the Utah backcountry crawling through sage after bison, I think you stay friends for life.”

Aside from the enduring friendship he gained, Flannery says creating the film was a “full learning experience” that opened his eyes to the power of film.

“I saw that was my calling,” he says.

It didn’t hurt having Lancaster, a skilled cinematographer, as a partner. Raised in Reno, Lancaster studied mechanical engineering at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo. But after discovering he did not enjoy that line of work, he took up cinematography about 10 years ago.

“I’ve always had a deep fascination with wildlife. I watched The Discovery Channel and Animal Planet. Steve Irwin was the man!” says Lancaster. “I was glued to that show when I was young. We’ve emulated that style of following someone around and learning about wildlife.”

‘Not Promoters’

Following the success of The Last Herd, Flannery and Lancaster created another documentary called Legacy about the Chinese railroad workers who blasted their way through solid rock on Donner Summit to build the Transcontinental Railroad. The film premiered in 2020 and has since been screened around the country.

The two friends were on a roll.

“After making a few documentaries, we wanted to try something different, and we leveraged the social media space for conservation education,” says Flannery.

Joe Flannery interviews Matt Johnson from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife for Where the Wild Roam’s Wild California Salmon episode, courtesy photo

So far, they have filmed more than 45 episodes of Where the Wild Roam and are slowly editing and getting the shows out to the public through their YouTube channel. They are self-funded, usually sleeping in a truck when not filming and hiking around in rough terrain.

They recently completed a series called Sierra North featuring the Middle Truckee River watershed, with episode titles that include Mountain Meadows, The Last Tahoe Pikas, Black Bears, Beavers are Back, The Amazing Aspen and Sierra Deer Migration.

“We love telling stories, but are not promoters,” says Flannery. “We have busy, demanding jobs and daughters to raise. We are at the mercy of our own funding and schedules. We pick a story we want to tell. When you watch episodes, you are watching us discovering the landscape.”

Adds Lancaster: “We just want to educate people. For them to care, you have to show them and teach them about how cool it all is—what makes our world so intriguing. There is nothing like being outside in the wilderness.”

While they are bare bones in their filming techniques, they use wildlife cameras extensively to capture the animals as up close as possible.

“We’ve had elk stomp our wildlife cameras, bears carry them away, cows damage them—five were destroyed in the Dixie Fire,” says Flannery.

Lancaster says while he loves the work, it certainly has its challenges. The biggest may be carrying all that heavy camera equipment on often arduous hikes, and sometimes wandering around trying to find their missing wildlife cameras.

Then there was the time they were filming palm canyons in the Southern California desert. It was late spring and well over 100 degrees as they made their way up a canyon. Flannery assured his partner that there was a spring of cool water up ahead. They eventually found it and excitedly jumped in. After a few minutes, however, Flannery yelled, “Get out of the water, Kyle!” They emerged covered in leeches.

Education is Key

From his years working for the Forest Service, Flannery remembers the “Three E’s” approach to protecting natural resources.

“Engineering, education and enforcement—and the last has the least effect,” he says.

Engineering involves technology or objects to protect the environment (public restrooms, bear-proof garbage containers, signs, fences). Enforcement, while sometimes effective, often comes too late, since the negative action has already taken place. Education, though, Flannery believes, has the best shot of achieving a positive outcome. The more people learn about the environment, the more they want to protect it.

Flannery says it’s easy for somebody in the conservation field to be pessimistic about the state of the environment.

The thought often is, “People are bad. People don’t care,” says Flannery. “But I think people are generally good and they care, and they just don’t know. They don’t understand the complexity and there is a vacuum of education. We believe people are good and if well informed, they will make the right decisions.”

Tim Hauserman has lived in Tahoe since he was 2. His latest book, Going it Alone: Ramblings and Reflections From the Trail, is a memoir about solo hiking misadventures.

No Comments