30 Jun Saving the River at its Source

In a remote granite bowl on the western Sierra Crest, unassuming snowfields melt into small braided streams among mule’s ear flowers and pines, slowly gathering together and gaining force, cutting deeper and deeper into the soil and rock, eventually forming the mighty American River.

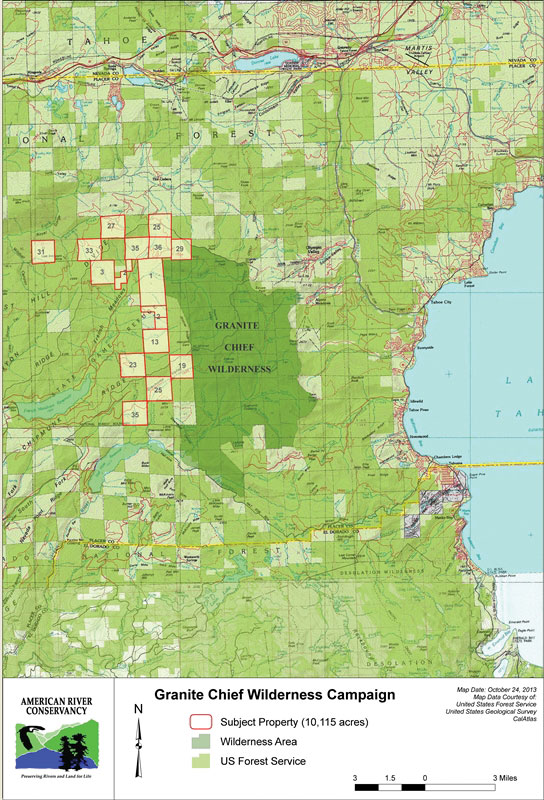

Lying on the harder-to-access western edge of Granite Chief Wilderness, just beyond Squaw Valley, over 10,115 acres of black oak, red fir, cedar and pine on the headwaters of the Middle Fork of the American River have largely escaped the attention given to other popular areas near Lake Tahoe.

This property hasn’t gone untouched, however. Since it was granted to the Pacific Railroad as part of the checkerboard pattern designed to help route and fund the transcontinental connector in the 1860s, it has been sold between various timber firms and logged somewhere around three or four times since the 1920s.

Today, as evidenced by California’s recent drought, large wildfires like 2014’s King Fire, and the growing number of dying trees across the Sierra, properties like this are becoming more and more important, conservationists say.

“We’re interested in headwaters because braided streams coming off of snowfields get a lot of bang for your buck,” says Alan Ehrgott, executive director at the American River Conservancy, which purchased the property last summer. “About 20 percent of a watershed can be represented in a small area with headwaters like this.”

After a decade of negotiations with Simorg, the previous property owners, American River Conservancy, aided by the Northern Sierra Partnership and the Nature Conservancy, finally closed at a price of $10,115,000.

“This property has been of long-standing interest to the Northern Sierra Partnership,” says Lucy Blake, president of the partnership. “In addition to being a priority for recreation, it is also a priority for the stewardship of the watershed of the American River.”

It was the largest remaining piece of unprotected private land south of Donner Summit along the crest, she adds.

The Nature Conservancy, in addition to raising funds for the purchase price, is assisting in planning and implementing restoration aimed at making a healthier forest in the face of fire, drought and climate change.

“There are serious issues throughout the Sierra Nevada with unhealthy forests, insects, disease, drought and climate change. It’s not good for nature or for people,” says David Edelson, the Sierra Nevada project director for the Nature Conservancy. “In our view, it’s important to increase the pace and scale of ecological forest management.”

With the property preserved and permits either processing or in place for a number of trail and restoration projects, the next few years will be busy for the three nonprofits working on the headwaters of the American River.

Over the next three years, the three groups will work to remove 42 miles of unneeded logging roads and 27 culverts, all of which interrupt the natural movement of water over the landscape and contribute to erosion, Ehrgott says, adding that workers will leave key fire roads for the Forest Service to use for firefighting.

“There are key trails through the property, including seven or eight miles of the Western States and Tevis Cup [100-mile trail races], so one of the many benefits of this acquisition is to secure the last remaining private portion of that trail to create a public easement,” Ehrgott says.

The property plans to link existing trailheads such as Granite Chief Wilderness and Talbot Creek Road, and a planned 4.1 miles of new trail will link with existing routes for a new loop.

“We would like to see the forest preserved and retain it in a more old-growth trajectory with groves of older trees,” Ehrgott says. “There’s spotted owl, goshawk and about 20 miles of Blue Ribbon trout stream on the property itself.”

According to Ehrgott, the property has been a wildlife refuge since 1911 in reaction to hunting pressures on the area.

Because of old logging practices, much of the property has dense young stands of trees growing closely together, rather than the natural mix of more widely spaced trees that make for a healthier forest.

“It’s in need of thinning and active management to promote healthier forest conditions,” Edelson says.

That forest management plan also aims to reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfire, as so poignantly demonstrated by the King Fire, which came very close to this property.

“There have been some mega fires on the west slope. A lot of that comes from an imbalance in the forest,” Ehrgott says. “We’re hoping to keep this forest standing, to keep it from burning completely.”

Overly dense regrowth from past logging practices poses the greatest risk, so management is designed to promote larger trees, Edelson says.

Reducing the density of young, small trees, lowering the risk of catastrophic wildfire and improving wetlands in the area all add up to a more secure, cleaner source of water for downstream users in the foothills, Central Valley and beyond.

“Downstream users have directly experienced pretty significant degradation of water quality in the aftermath of the King Fire, with some significant restoration costs,” Edelson says. “Our hope here is to do some interesting research to find the link between healthier forest and downstream water supply.”

The partnership also plans to remove conifers and reintroduce aspens to wet meadow systems in order to create a healthier watershed.

“There are a lot of wet meadow systems. Even after four years of drought, it was amazing to see the amount of water being pumped out of these systems in the fall,” Ehrgott says.

Beyond the American River Conservancy, Northern Sierra Partnership and the Nature Conservancy, the project has been well supported. “We haven’t had much opposition; it’s really a win-win situation,” Ehrgott says. “We’re not opposed to logging in certain places, but in this particular area the wildlife, water and recreation will outweigh the loss of timber.”

Image courtesy American River Conservancy

Gabriel Poll

Posted at 15:43h, 17 AprilHi Alan,

long ago and far away we lived together in the big house in Riverside with David, Kirk, etc. I ran across your name and just wanted to see what you have been up to, as I expected big things from you. I remember our trip down Baja in your 68′ green and white VW van, running into the Mexican National observatory, finding and taking a boa we named Rosy with us for a few days and ultimately ending up on the beach in Punta de Estrella near San Filipe. I so enjoyed visiting the cabin that your father had built in the desert with Jim and Richard Sailor’s dad, and the adventures in living with 6 roommates, and the rest of the two years I lived there. What a group. Those were some of the most fun days of my life and I remember you so fondly. I am so proud of you in achieving so many of your goals in preserving and guiding others in the enjoyment of the environment.

I have not done what you have, but have enjoyed a very full and wonderful life with my incredible wife of 42 years, had a wonderful son and daughter who have given me 2 grandsons and two granddaughters, ages 3-9, My son did go to UCSB, got a masters in Environmental and is a project manager for and environmental company, living the life in Santa Barbara and specializing in air quality management. I am so proud of him as he totally practices what he preaches and makes sure his carbon footprint is as small as possible.

I am equally as proud of my daughter who the business administrator for my law firm. We just had our 32 year in operation and I will be retiring this year to enjoy the life of travel and my family, with a good sprinkling of Dodger games mixed in. Hope all is well with you.

Just wanted to drop you a note to say hi.

Best,

Gabe