06 Jul Swimming Back from the Brink

Without question, the principal environmental feature defining the Lake Tahoe region is The Lake, and by extension the watercourses making up the entire Truckee River watershed. Less than 200 years ago, one organism, the Lahontan cutthroat trout, dominated this system of lakes, rivers and streams. These large trout evolved in ancient Lake Lahontan and reached phenomenal sizes in the remnant lakes as Lake Lahontan receded. Stories and even photos of Lahontan cutthroat trout caught at Pyramid Lake suggest these fish, which fed primarily on other fish such as chub and suckers, could exceed 60 pounds.

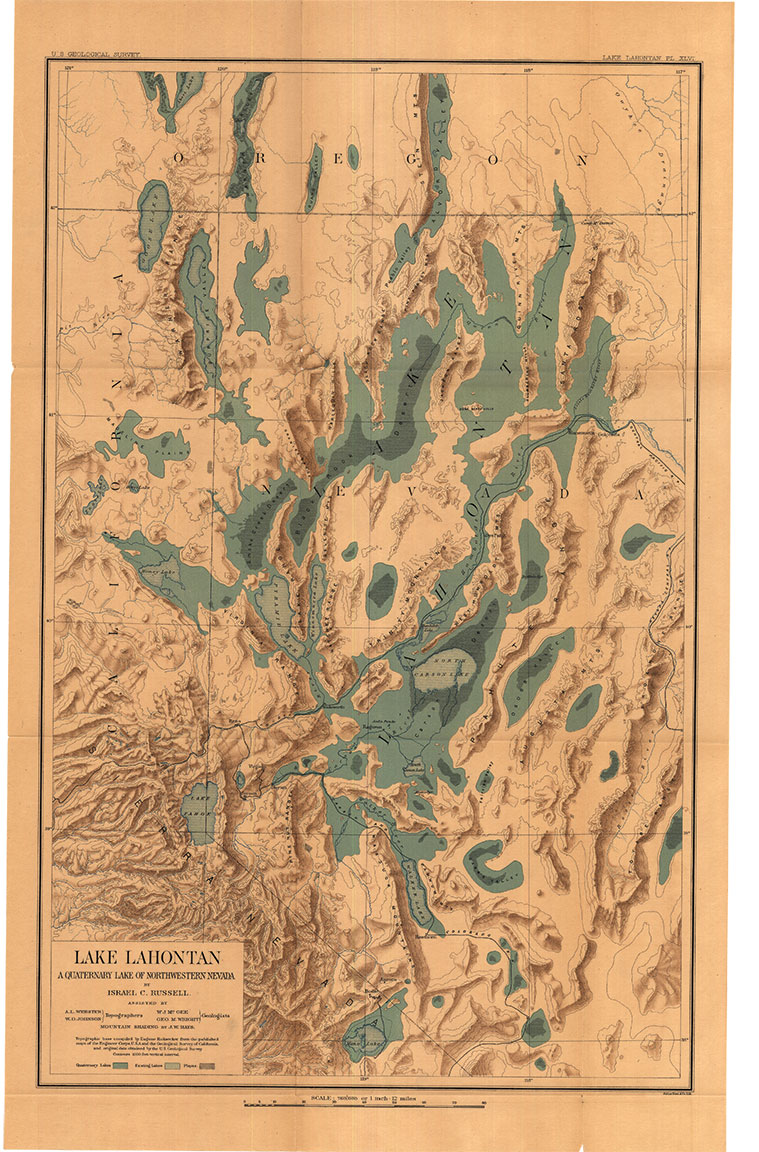

Ancient Lake Lahontan once covered much of Nevada

and was home to giant Lahontan Cutthroat Trout

Sadly, the fortunes of the Lahontan cutthroat trout changed in the middle of the nineteenth century. Beginning around 1859, these fish were commercially harvested and shipped throughout the West to feed countless boomtowns and mining camps. Researchers have estimated that as many as a million pounds of trout per year were taken out of the system between 1860 and 1920.

During this time, mountainsides were stripped of their trees to provide mine supports and silt from the subsequent erosion choked critical spawning stream habitats. The Derby Dam, completed in 1905, may have been the final and most serious blow for the system as a whole, interrupting the early spring runs from Pyramid to the rest of the watershed. In 1888, lake trout, a nonnative char, were introduced into Lake Tahoe, and quickly outcompeted and preyed upon the cutthroats. Additional introductions of nonnative rainbow, brook and brown trout piled on the pressures of competition, hybridization (with the rainbows) and predation, and large die-offs occurred in Pyramid Lake in the 1920s, possibly the result of disease spreading from these introductions.

The last recorded spawning run of Lahontan cutthroat trout in the Truckee River was in 1938; by the 1940s the strain was gone and declared extinct. Amazingly, a remnant population was discovered in the 1970s in a high mountain creek near the border of Utah and Nevada. How they came to be there in the first place, were discovered decades later, and collected just a few years before a wildfire killed off that population, is another fascinating saga unto itself, but the important result is that the original strain has now been brought back from extinction and is once again growing to large size in Pyramid Lake.

Elsewhere in the Truckee River watershed, reintroduction has been more challenging. Other trout species (especially brown trout, originally from Europe) eat small cutthroat or hybridize with them. Thus, they can only be successfully re-stocked where the watershed has a relatively pure native fauna, and to do that means getting rid of nonnative fish, something that is only feasible for a handful of headwaters such as Meiss Country above the Upper Truckee Falls, above Fallen Leaf Lake and Independence Lake. This is easier said than done and would be downright impossible in Lake Tahoe itself. Lake trout are very well established, as are Kokanee salmon, originally introduced in 1944. The various other nonnative trout are well established throughout the Truckee River watershed, and tens of thousands of trout continue to be stocked into the system annually.

Local angler and conservationist, Mikey Wier holds a 34-inch, 16-pound

rainbow trout caught on the fly at Fanny Bridge that was released off the

West Shore of Lake Tahoe, photo by Stefan McLeod

While it would be wonderful to re-establish a native fish fauna in Lake Tahoe, authorities are having enough trouble simply containing the ongoing invasion of new species, everything from aquatic plants like Eurasian milfoil, a host of clams, mussels and snails, and a surprising number of warm water fish species.

By the mid to late 1970s, a variety of nonnative fish species were showing up in the nearshore and surrounding marsh environments of The Lake. Along with the increase in warm water fish, researchers have observed a continued decline since 1999 in the few remaining native fish species. Typically, where nonnatives are present, no native fish are caught during surveys.

How these species impact the rest of the ecosystem is worth considering, however, as observational evidence suggests these warm water nonnatives contribute significantly to the diets of osprey, eagles, herons and possibly otters (which appear to have reestablished in Tahoe over the last 12 to 15 years).

Most of the fish I see taken by osprey around South Lake Tahoe are bullhead catfish or goldfish. I have witnessed a black-crowned night-heron catch a dozen small bullhead in 45 minutes in Pope’s Marsh. This relationship is worth investigating. Luckily, these fish seem to be confined to shallower bays, the nearshore and surrounding marshes, and exhibit slow growth. There is cause for concern, however, in the discovery of smallmouth bass in The Lake two years ago, and this cold water species’ ability to exist away from the nearshore and shallow water environments.

Presumably, anglers wishing to establish fisheries for other species introduced all these fish. The desire to meddle with Tahoe’s food web is not a new phenomenon, nor has it been restricted to illegal introductions. Consider the lake trout, Kokanee, Mysis shrimp and signal crayfish, all of which have caused profound, unexpected disruptions in The Lake’s ecosystem. Some introductions may have been pets dumped into The Lake.

The massive goldfish around the Tahoe Keys are an obvious product of this type of abandonment, but the phenomenon is not restricted to goldfish. Every couple of years, I spot a few red-eared slider turtles in Tahoe Keys. Most surprising of all, in August 2014, a two-foot ray was photographed by a kayaker near Kiva Beach.

Salmon swimming in South Lake Tahoe’s Taylor Creek, photo by Rafal Bogowolski

Nearly two centuries of damage to the environment of Lake Tahoe and the Truckee River watershed has led to complex and dynamic changes in the watershed’s food web, often in very unexpected ways.

We may be able to restore portions of the fishery to a native fauna, while other parts will always have introduced species and may best be managed for sport fishing. Among the nearshore, we can hope for containment of aquatic invasives, and the researchers working on this system believe that this is a very real possibility.

But one thing is for certain: We need to stop adding new species into the watershed.

Will Richardson is cofounder of the Tahoe Institute for Natural Science; learn more here.

No Comments