25 Jun The Yuba River: From Wild West to Wild and Scenic

The three forks of the Yuba River have been dammed, mined and plumbed, but their beauty still captivates conservationists and recreationists alike

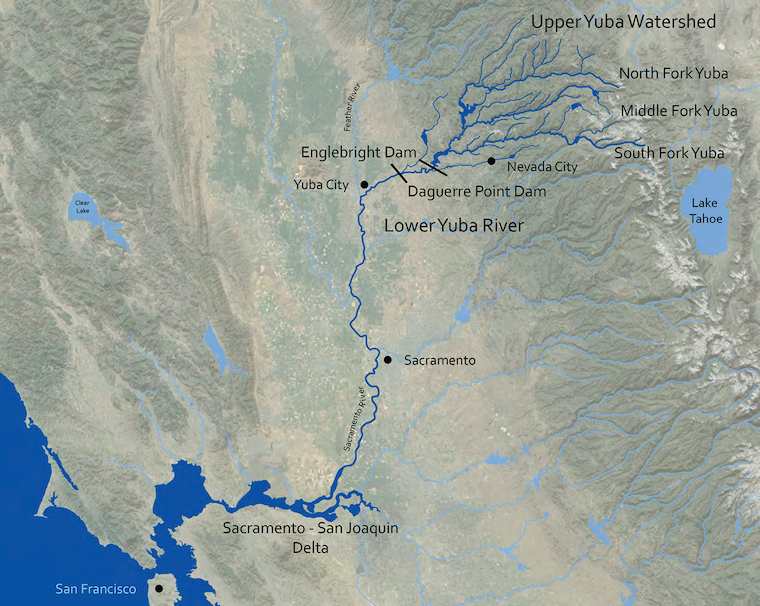

From Donner Pass in the south to Yuba Pass in the north, snow melting beneath the gnarled pines of the Sierra Crest gathers in streams and gains strength, cutting deeper and deeper creases into the earth as it flows west. Combining into the South Yuba, Middle Yuba and North Yuba, waters accumulated from 1,300 square miles of the northern Sierra eventually join forces below Grass Valley, slowing into a braided main stem before passing through Yuba City. The Yuba joins the Feather River and then the Sacramento River in turn on its journey to the California Delta and out to sea.

For long, idyllic stretches, the Yuba River alternates between deep, placid emerald pools and frothing whitewater cascading over smooth silver granite boulders. The unrelenting force of the river has sculpted the jumbled rock, boring holes through it, and painting it in minerals leaving streaks of orange, gold and black. Looming above its banks, steep canyon walls clad in deep green forests that seem to defy gravity reach up toward the sky.

Host to iconic chapters of California history and other lessons almost forgotten by time, pristine in stretches and seemingly hopelessly mired by the hand of man in others, the Yuba River can be hard to neatly define or characterize.

And because of that—its beauty, the lessons it teaches, the resources it provides—the Yuba has a way of getting into the hearts of people who visit its cool, clear waters. From Native Americans to 49ers, loggers to hippies, the Yuba has affected many, in turn influencing art, economics and politics.

“The Yuba River is a teacher. It’s a laboratory. You can’t help but fall in love with it, and if you care about it, you just have to become a part of it,” says Hank Meals, a field historian who came to the river in the 1960s and worked for the US Forest Service in the Yuba River area for many years.

Water in the South Yuba River flows over granite boulders, some of which were swept downriver by hydraulic mining operations during the California Gold Rush, photo by Greyson Howard

Gold Rush History and Forgotten Stories

“We think about this place being populated with the Gold Rush, and history only going as far back as white settlement,” says Melinda Booth, executive director of the South Yuba River Citizen’s League. “But within the watershed, the Washoe, the Mountain Maidu and the Nisenan inhabited this place long before. When gold was discovered, their land was taken, not dissimilar to stories from across the United States.”

Greg Williams, executive director of the Sierra Buttes Trail Stewardship that builds and maintains the trails of the North Yuba, among other places, is a descendant of the Miwok Tribe, but has found tribal history of the region scarce.

Hydraulic mining along the Yuba River, photo courtesy Library of Congress

“My great, great, great grandfather was in the area when the Gold Rush started. It hit the area so hard and fast that it displaced the tribe,” Williams says. “My family didn’t talk a lot about it. It’s like having grandparents who have been to war—they just didn’t want to talk about it. There aren’t many records of the tribes being displaced and murdered.”

That knowledge and that connection were largely lost when the California Gold Rush inundated the Sierra foothills with 49ers.

“Gold was found on the South Fork of the American River in January of 1848, and by June it had been found on the Yuba River. By 1849 people were pouring in,” Meals says.

The population swelled, to the point that the now tiny town of Downieville missed out on being the state’s capital by a matter of a few votes, says Williams.

And while gold was at first plentiful and easy to find on the Yuba, miners’ unquenchable thirst for the ore required significant innovation in the watershed—developing mining technologies that outpaced other areas.

“People were learning how to get gold out of hard rock. They developed hydraulic mining. It was the Silicon Valley of the era,” Meals says.

Other technological firsts included the Pelton wheel, a water wheel used to generate power that was the predecessor of the hydroelectric dam, as well as the first long-distance phone line, which allowed communications between dam operators, and more, says Meals.

Deposits from the Tail Flumes on the Yuba River in 1866, photo courtesy Library of Congress

Naturally, a myriad of other enterprises sprung up in the region alongside mining, from timber harvest to transportation. Agriculture developed in the Central Valley soon linked to the rest of the country by the transcontinental railroad.

Stars like opera singer Emma Nevada were born in the gold mining towns of the Yuba River, and others like Lola Montez would leave their mark performing for the booming population.

And while new businesses flourished, gold quickly became harder and harder to find, leading increasingly corporatized mining interests to blast away entire hillsides with hydraulic mining. Those tailings flowed downstream—literal tons of gravel and debris—bringing mining into conflict with farmers.

The Sawyer Decision of 1884, often cited as the first environmental lawsuit, saw mining lose to the growing interests and power of those farmers, says Ashley Overhouse, river policy manager for the South Yuba River Citizens League. The result ultimately limited hydraulic mining in the Yuba.

“This decision was acknowledging for the first time that water was the new gold, whether they knew it or not,” says Overhouse. The effects of this decision would be felt in water policy for decades to come.

Other laws on the national stage started to be influenced by people who had settled in the region, Meals says. Nevada City resident Aaron Sargent championed the 19th Amendment, giving women the right to vote, although his role in Chinese Exclusion is often brushed over, Meals says.

And while the Gold Rush was quickly winding down, towns and industries were already established in the Yuba River Watershed, changing its face forever. Englebright Dam was constructed with the sole purpose of stopping sediment from flowing downstream toward the farms below, joined over time by 29 other dams, 20 powerhouses and 500 miles of canals crisscrossing the watershed, according to conservation group American Rivers.

Following the Gold Rush, logging left its mark as well, stripping hillsides of trees and further redirecting water through flumes to transport timber.

“You look at old pictures of Downieville and there wasn’t a tree anywhere near town,” Williams says.

The mark of extractive uses didn’t end there, with recent illegal marijuana grows diverting water while also introducing fertilizers and leaking pesticides into the river.

But the winds began to shift back in the 1960s, thanks to the unlikely influence of the hippy movement working its way out of San Francisco into rural areas as its followers sought a more natural setting.

When Zen poet Gary Snyder took to the Yuba River Watershed, Meals was among the new settlers seeking an alternative way of life.

“All the hippies came here in 1969 and lived on the river for a while,” Meals says. “I incrementally fell in love with the place, got a job with the Forest Service as an archeologist and got to know the history, the land, and now I can’t get out of here because this place is so inspirational.”

Initially clashing with loggers, Meals says this growing group nevertheless began to change the culture of the region in art, food, literature and in a deep passion for caring for the natural landscape, from which a direct line to modern environmentalism can be drawn.

The town of Downieville along the North Yuba River in 1933, photo courtesy Library of Congress

Fighting for the River

While the Sawyer Decision was the first of what today would be considered environmental protections for the Yuba River, there was a lot more work to be done.

“In 1983 some dams were proposed on the South Yuba River, and the community decided that wasn’t what they wanted for the river,” Booth says. “They came together and started fighting these dams in what would become a 16-year-long fight to save the river.”

Loves Falls along the North Yuba River near Sierra City, photo by Scott Sady

The South Yuba River Citizen’s League (SYRCL) was formed out of that fight, growing to become one of the largest single-river watershed environmental organizations in the country, employing more than 20 people today.

Longtime board member John Regan came on in the late ’90s as a part of that fight, falling in love with the river in the process.

“People talk about being captured by the Yuba, and that’s what happened to me. I came to a SYRCL fundraiser, a local film about the Yuba on a Wednesday or Thursday night, and couldn’t believe they had packed the theater,” Regan says. “The next day I spent the day on the river, and decided then this is where I wanted to live.”

Regan brought a background of political campaigning, and immediately went to work in Sacramento, seeking the state Wild and Scenic River designation.

“We were able to find an ally in State Senator Byron Sher. He was a champion of the river,” says Regan.

Regan and recently elected Nevada County Supervisor Izzy Martin began making regular trips to the capitol, lobbying for SB 496 to win the designation.

The South Yuba River Citizen’s League won Wild and Scenic status in 1999, permanently protecting 39 miles of the South Yuba after a 16-year-long fight—from near Spaulding Dam by the intersection of Highway 20 and Interstate 80 to the next dam at Englebright Reservoir.

“It showed we could win. We could beat the big guys with way more money, more pull and more experience,” Regan says.

The passionate advocates who came together had a choice to make.

“This was our goal. What do we do now?” Booth says of the turning point in 1999. “They decided, gosh, we’re not actually done, we’ve learned that this is an incredibly impacted watershed, one of the most plumbed watersheds in the state, and we want to help restore it, to return the native salmon, and to take on a broader purpose after that success.”

Protecting the Yuba River Watershed means addressing problems both old and new.

Gravel washed down by hydraulic mining still causes problems in the lower Yuba River. Mercury, used to help extract gold, still taints the water in many places. The unmapped tangle of mines still waits like an unexploded bomb. As recently as September 2019, a mysterious yellow plume threatened the safety of river users, and remains in large part a mystery today, Booth says.

New threats, from road salts coming off Interstate 80 into the South Yuba to climate change and catastrophic wildfire, loom large. Increasing recreation on the river, a welcomed use that brings awareness to the Yuba, also brings garbage, unsanitary conditions and the risk of fire in remote, steep canyons that are difficult to evacuate or access by firefighters, Booth says.

The South Yuba River Citizen’s League has expanded its reach, now opposing the proposed Centennial Dam on the Bear River, lovingly called the fourth fork of the Yuba thanks to the waters shared between them by flumes and ditches.

“I think it is so far-fetched to propose an on-stream reservoir in 2020, just from a financial standpoint alone,” Overhouse says. “There are so many more important priorities in the watershed to focus on.”

Along with protecting the river from these potential threats, lovers of the Yuba want to take positive steps toward restoration as well, with goals to reintroduce salmon and steelhead to native spawning grounds, remove out-of-date dams that stand in their way, restore wet meadows, and promote healthy forests that are all intertwined in the complex web that makes up a watershed.

A map of the Yuba River Watershed, courtesy South Yuba River Citizen’s League

The Yuba Today

While the challenges past, present and future sound daunting, the Yuba River remains a beautiful place that captivates those who visit, swim, fish or paddle—even if they aren’t aware of its complex past.

“Many of the boulders in the river people love to sun themselves on today are actually there because of hydraulic mining,” Regan says. “It was absolute devastation for the environment and the indigenous people of the region, but it created something beautiful. That says something about the power of nature.”

Likewise, the iconic trails of Downieville—now the lifeblood of a town that lost its mining and lumber jobs long ago—are owed to the miners who cut them into the rock and dirt so long ago, Williams says.

“We want to not just attract visitors but to attract residents. We want to bring working families back,” Williams says of Downieville and the surrounding small communities. “We want people to be tied to these lands, to be stewards, to vote for the environment. We think recreation can be sustainable for our community.”

Even at Malakoff Diggins State Park, the poster child of the destructive forces of hydraulic mining, Meals sees the lessons of the Yuba still being taught.

“There’s poetry in a mine that was singled out for environmental damage potentially making the transition to solar power,” Meals says of plans for the state park. “It takes people a while to figure out they’re part of an ecosystem on a creek or a ridge, that what you do affects your neighbor, but that’s what the Yuba River teaches us.”

In the end, there’s still much to do to protect the Yuba River, but its unique charms still seem to capture plenty of passionate people willing to take up the work.

Greyson Howard is a writer and communications director for the Truckee Donner Land Trust. He enjoys the Yuba River, whether it’s swimming in the South Yuba or mountain biking above the North Yuba in Downieville.

Sue Cejner Moyers

Posted at 12:34h, 06 SeptemberHello, Sue here from Yu ba County Historical Resouces Commission. Doing research of the Swan history for upcoming California Swan Festival. Do you have any history of the bird and wildlife in the Yuba-Sutter area? Let me know, thanks

!