24 Sep UC Davis Grads to Take on Tahoe Invasive Species with Dog Treats

If you identified water fleas as the central piece to the problematic puzzle of declining clarity at Lake Tahoe, congratulations. And if you named dog treats as a viable solution to ecological problems at the lake, you win again.

However fantastic it may sound, a graduate project helmed by UC Davis students that calls for the removal of an invasive shrimp from Lake Tahoe to be transformed into healthy dog treats has a chance to not only restore the ecological fortunes of the lake, but also to serve as a test case for making invasive species removal cost-effective.

“We wanted to come up with something that would help restore Lake Tahoe’s ecosystem, drive awareness about the problems and prove economically sustainable,” says Yuan Cheng, a recent graduate from the University of California, Davis Graduate School of Management.

What Cheng and his team came up with was dog biscuits.

Water Fleas

The water fleas at play are not fleas, per se. Water fleas are informal names for two small crustaceans that traditionally flourished in Lake Tahoe called Bosmina and Daphnia. The two planktonic crustaceans are called water fleas because the way they move through the water resembles the abrupt jumps of fleas.

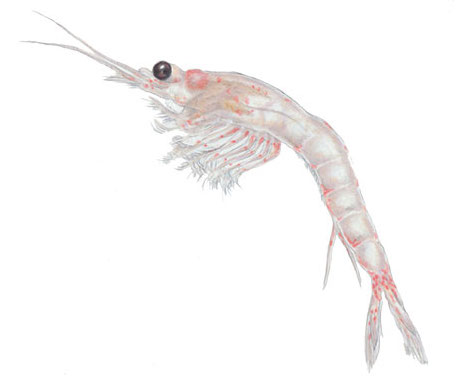

Mysis shrimp

The small organisms play a big role in Tahoe’s ecological functioning as they feed on fine particles and algae, two of the major culprits in the steady decline in Tahoe’s famed clarity.

But Bosmina and Daphnia have been prevented from carrying out their fundamental role in Tahoe’s food web since the introduction of mysis (alternately known as mysid) shrimp into Lake Tahoe in the mid-1960s.

Wildlife managers thought at the time that the shrimp would serve as food for Mackinaw and Kokanee salmon, two nonnative game fish. Instead, the shrimp dive deep during the day, below where the targeted fish swim and feed, and only come up to feed on the Bosmina and Daphnia, which has reduced their numbers.

“They (Bosmina and Daphnia) are the natural vacuum cleaners of the lake,” says Heather Segale with the Tahoe Environmental Research Center (TERC).

This, in turn, means that fewer small organisms are feeding on the algae and fine sediment responsible for much of the clarity decline in the last half-century.

Researchers at TERC are now targeting the shrimp—starting with Emerald Bay, where the creatures have secured a foothold in the local ecosystem—with an eye toward coming up with an effective control and removal program.

The problem with such invasive species programs is that successful eradication is nearly impossible, and control programs are costly and thus unsustainable over the long term.

The UC Davis team at Lake Tahoe, photo courtesy UC Davis Tahoe Environmental Research Center

Dog Treats

When Cheng and his teammates were searching for an idea to transform the problem of invasive shrimp into a potentially lucrative business opportunity, dog treats were not top of mind.

But they quickly glommed onto the idea after a few things became apparent.

“Dog treats are a $4 billion market in the United States and growing,” Cheng says. “But there is something about dogs that tie us to nature, so from an awareness standpoint it helps us get the story out.”

Mysis dog treat prototypes prepared by the UC Davis team, photo courtesy UC Davis Tahoe Environmental Research Center

Mysis shrimp in particular are conducive to dog treat production because of their health benefits.

“Mysis shrimp have a high concentration of omega-3 fatty acids that promote joint health and skin health in dogs,” says Myhan Nguyen, a food scientist who joined Cheng’s team. “So besides the regenerative sustainability aspect, there is a health benefit.”

Liz McAllister, who studied design at UC Davis and currently works as a program coordinator for the Water Education Foundation, is using her marketing experience to bring seemingly disparate worlds together.

“Maybe you have someone who loves dogs and is really involved in the pet community that may not be an outdoors person that can get involved in this environmental issue,” McAllister says. “On the other hand, maybe you have an avid skier that may not know so much about pet health. It’s about bringing these worlds together.”

McAllister is working on a marketing program that involves everything from packaging the treats to developing a logo and formulating a communications package.

Nguyen, meanwhile, is trying different recipes in her kitchen, experimenting with different oils and flours to come up with something attractive, healthy and affordable.

Cheng continues to work with partners in TERC, navigating the coronavirus impacts and looking to help bring the project to fruition in a timely manner.

Challenges remain.

For one thing, the group has to continue to work with TERC to trawl for the invasive shrimp in Emerald Bay and other parts of the lake. That aspect can prove time intensive and costly. Because the shrimp are light-sensitive, they only emerge from the depths to hunt at night, meaning that trawling can only happen after the sun goes down.

Cheng says it remains to be seen how efficient they can be in capturing enough shrimp to create a mass-produced product.

“We have to see the harvest efficiency of the shrimp before we can know if it’s possible to scale efficiently and make a business out of it,” he says.

But the group is also committed to making a business where profit is not the primary reason for existence, which is why the enterprise will take the form of a nonprofit.

“This project is about getting rid of invasive species, and if you have the wrong financial incentives you will end up with more shrimp rather than less,” Cheng says.

In other words, if the business proved too successful, the pressure would mount to introduce more shrimp into the system to sustain revenues. But instead, Cheng and the others are looking for a way to offset the costs of invasive species control in Lake Tahoe.

“We are trying to change an ecosystem by removing Mysis shrimp in order to restore it,” he says.

Jane Hartman

Posted at 08:53h, 12 OctoberMarvelous! Best wishes for success!