27 Sep Adrian Ballinger: Elevating His Game

Tahoe-based mountaineer adds another Himalayan giant to his impressive résumé of ski descents

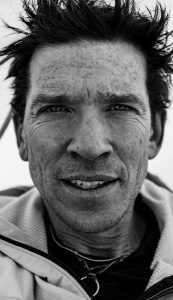

Ballinger evaluates a steep slope after summiting Makalu

On Monday, May 9, 2022, Adrian Ballinger stood on the summit of Makalu, the fifth-highest peak in the world at 27,776 feet. Ballinger, the affable mountain guide and CEO of Tahoe-based Alpenglow Expeditions, is no stranger to standing on the summit of the world’s tallest peaks. In total, he’s summited 17 peaks of 8,000 meters or higher in his quarter century of guiding and climbing, and is only the fourth American to have summited K2 and Mount Everest without supplemental oxygen.

But on this day, at that moment, Ballinger was not pondering another routine descent to camp. He was set to make the first true ski descent of Makalu, the rocky, technical Himalayan incisor located about 10 miles from Everest.

Forgive the 46-year-old for having some trepidation while staring at the abyss below. After all, Makalu repelled him on two previous ski attempts, first in 2012 and again in 2015, and conditions on this day weren’t exactly inviting.

“Makalu is so technical and there is so much rock and it’s so steep, which is what attracted me to it in the first place, but there isn’t a natural ski line,” Ballinger says while sipping coffee in Olympic Valley on a sunny summer day. “I was constantly looking on the way up and trying to find where the snow links together. It was a very dry spring, good for climbing, lots of blue ice, but it was not good for skiing. Actually, the ski conditions couldn’t have been any worse. I was just trying to find skiable, edgeable snow.”

Ballinger pictured the night before his summit and ski descent of Makalu

In his two previous Makalu ski attempts, Ballinger says that wasn’t an issue. He was on the mountain during the post-monsoon season, but both efforts ended in failure, not from a lack of preparation or ability but because of avalanche danger. During the post-monsoon season, the Himalaya is blanketed with snow and receives frequent storms, which provides better snow coverage but comes with an increased risk of avalanches. It didn’t feel right either time, so Ballinger chose to delay what soon became a decade-long objective that never escaped his imagination.

“I don’t think Adrian chooses to ski the tallest mountains because he assumes conditions will be anything but horrible,” says Ballinger’s wife, Emily Harrington, who is also an accomplished climber. “He is not in it for the skiing, really. It is more important to him about the adventure and the challenge and what is associated with that.

“There is a lot of risk and a lot of creativity and a lot of challenges, logistically, on big mountains. It’s not simple. He loves those challenges. It’s just kind of what he does. He loves having big, audacious goals that are complicated and require complex decision-making. For him, that was skiing Makalu.”

A Multitalented Mountaineer

Ballinger, who was born in the United Kingdom and moved to Lake Tahoe in 2008 after a stint in Aspen, Colorado, has developed a reputation as a safe, yet bold, climber and skier. He’s a paradoxical dynamo who has combined all the disciplines—high-altitude climbing, rock climbing, big-mountain skiing—and has always returned home. As a guide, he has an even stronger reputation.

Makalu, the fifth-highest peak in the world, towers above the Himalayan landscape

“He is an incredibly professional mountain guide and is so personable,” says Colorado-based mountaineer Ellen Miller, the first American woman to summit Everest from both the Nepalese and Tibetan sides of the mountain. “I’ve learned a lot from Adrian.”

Miller, who met Ballinger during her climb of Lhotse in 2009, describes him as a natural leader with an infectiously relaxed yet confident demeanor—the kind of self-assurance that can only be achieved through years of ambitious and skillfully executed feats on the world’s tallest mountains.

“Even way back when,” says Miller, “I knew he was an incredible skier and that (skiing 8,000-meter peaks) was a dream in the background. As a matter of fact, when hearing about his Makalu ski descent, I knew he was the guy to do it. He was a good candidate for that because of his experience on technical terrain and at altitude. His skill level in all of the disciplines—extreme high altitude, ski mountaineering, technical rock—he is amazing at it all.”

But even this past spring, Ballinger was ready to turn around again. Always the mountain tactician, he correctly figured that a pre-monsoon attempt in spring would yield less avalanche danger. As it turned out, this past spring was one of the driest on record on Makalu, with 4 inches of snow falling in the 35 days he was in the Himalaya. After his fifth day on the mountain, he didn’t even carry an avalanche beacon, shovel or probe, which is “unheard of,” says Ballinger.

“The thing is, every step of the way on this mountain I was ready to bail and accept that I would not ski it if it didn’t feel right,” Ballinger says. “I have to come home alive. Knowing that, nobody was pressuring me to make bad decisions. Decision-making is really important to me. There are countless things that make you feel wrong on these mountains, and the big thing on Makalu and with me turning around has been avalanche conditions. Even without any avalanche danger, these mountains are so big, 8,000 feet of vertical, and somewhere on the mountain the conditions will be terrible.

Adrian Ballinger in the kitchen tent at base camp with Dorji Sonam Sherpa, Phu Rita “Nawang” Sherpa and Ngima Tenzing Sherpa

“During acclimatization I did a lot of skiing as high as 24,500 feet. I wondered if I should just climb the mountain and not ski, but every section was skiable. It wasn’t great, but it was skiable. It was high-consequence terrain and no fall zones, but it was edgeable and skiable.”

Generally speaking, skiing or snowboarding 8,000-meter peaks (above 26,246 feet, of which there are only 14 in the world) isn’t a popular activity. To thrust oneself into that group requires a rare fusion of sorts: being a high-altitude mountaineer, a technical climber and a highly competent skier or rider on conditions not usually found at ski resorts or in the backcountry. There are athletes who possess one or two of those attributes, but very few who possess all three.

“It takes a really high level of climbing and skill set,” says Kit DesLauriers, the first American woman to ski Everest, who was with Ballinger on Makalu during his 2015 attempt. “It’s also expensive and difficult and it’s just not an easy thing to do. There is only a small subset of people who find it fun and creative and aren’t put off by the training and skill set and the dangers.”

Ballinger, of course, is one of those people.

Adrian Ballinger assesses the route ahead before reaching Camp 2 during an acclimatization rotation before his summit bid

Performing at Altitude

So on May 9, while standing on the summit, Ballinger was ready to become the first American to ski from three 8,000-meter peaks. In 2011, he successfully climbed and skied 26,781-foot Manaslu, the eighth-highest peak in the world. Two years later, he climbed and skied 26,864-foot Cho Oyu, the sixth-highest peak in the world. In 2016, Ballinger and Harrington, his then-girlfriend, skied together from the summit of Cho Oyu.

But this past spring, Ballinger was skiing Makalu alone with Sherpa support nearby.

“In most athletic pursuits, whether it’s the big game day as a pro soccer or a pro basketball player, you are in your best position to be successful,” Ballinger says. “You’ve gotten massages, you’re well rested, maybe you had a coach for mental stuff. You are ready. But with big-mountain skiing, you literally feel as bad as you possibly can when you are on the summit, and you need to perform.”

He lowered himself about 50 feet from the summit to where he could begin his descent. In that respect, Ballinger is quick to point out that there should be an asterisk next to his “first true ski descent” tag. Not just was he unable to ski from the true summit, he used oxygen. He normally climbs 8,000-meter peaks without oxygen, but he decided that wasn’t an option on this expedition.

Ballinger skis below Camp 2 on Makalu, elevation 21,500 feet, after his successful summit

“Oxygen is clearly a performance-enhancing substance. It just is,” Ballinger says. “That doesn’t mean I don’t honor the ascents with oxygen or I don’t respect people who use oxygen. It’s still really freaking hard, but it’s harder without oxygen. All the big mountains before had been skied with oxygen: Jim Morrison and Hilaree Nelson on Lhotse, Marco Siffredi on Everest. But then the Polish kid (Andrzej Bargiel) went to K2 in 2018 and skied without oxygen, and he set the bar for pro skiers on big mountains.

“I was hoping to ski without oxygen. I am capable of summiting without oxygen, but all of my ski descents have been with oxygen. I find myself on the edge of making mistakes when I am skiing these big mountains, so I made the decision to use oxygen from 25,000 to 28,000 feet. That was a compromise, certainly less pure, but I definitely would have gotten myself killed trying to ski without oxygen in those conditions on Makalu.”

Once he clicked into his bindings, the descent began. The snow was never soft, always firm with edges chattering over high-consequence terrain. But after 11 hours and 8,500 feet of vertical terrain, Ballinger completed the first true ski descent from summit to camp on Makalu. He skied solo but with the aid of two climbing Sherpas and stayed near the fixed climbing ropes they had installed during the acclimatization period. He admits not having a partner to bounce ideas off and gain confidence through conversation was challenging, but in other ways he felt he wasn’t alone.

Adrian Ballinger is all smiles after summiting Makalu and making the first ski descent from the summit

New Priorities

In November, Ballinger and Harrington, who got married in Ecuador in 2021, will welcome a child into the world. Harrington, a sponsored North Face athlete, was skiing couloirs on Canada’s Baffin Island when her husband was making history by becoming the first to ski from Makalu. Ellen Miller calls Ballinger and Harrington the “climbing world’s power couple.”

“We were in contact with satellite texting,” says Harington. “It was a little bit stressful. I think for both of us, when we are doing something dangerous, it is kind of nice to be on our own, with our own objective. … But being 10 or 11 weeks pregnant, thinking, ‘Oh God, we are going to be parents and we are both doing these dangerous things,’ was more stressful than normal. But he made certain sacrifices and took less risk.”

While being a professional mountain guide, climber and skier—for both Harrington and Ballinger—might tweak their objectives as parents, it won’t remove them. For Ballinger, he acknowledges the highest remaining peak that hasn’t been skied is 28,169-foot Kangchenjunga, the third-highest peak in the world. For now, he’d prefer to savor his Makalu descent and not be seduced into future projects.

“This was such a big deal for me—10 years of work, three expeditions—and most big-mountain skiers are always focused on what is next and get pushed not by sponsors but by their own brains,” Ballinger says. “There’s a little depression after accomplishing a big goal and not having the next one planned. But that can be a pretty sketchy cycle … more risk, more risk … so I do not want to rush and think about what is next. I am so excited about what I did on Makalu.

“With that said, I do find it incredibly compelling to try and pull off the ones that haven’t been done, like Kangchenjunga.”

Jeremy Evans is a South Lake Tahoe-based author whose most recent book, See You Tomorrow, tells the story of snowboarder Marco Siffredi and his mysterious disappearance from Mount Everest in 2002.

No Comments